Earth:Quaternary extinction event

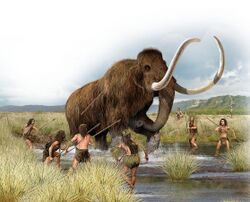

The latter half of the Late Pleistocene to the beginning of the Holocene (~50,000-10,000 years Before Present)[1] saw extinctions of numerous predominantly megafaunal species, which resulted in a collapse in faunal density and diversity across the globe. The extinctions during the Late Pleistocene are differentiated from previous extinctions by the widespread absence of ecological succession to replace these extinct megafaunal species,[2] and the regime shift of previously established faunal relationships and habitats as a consequence. The timing and severity of the extinctions varied by region and are thought to have been driven by varying combinations of human and climatic factors.[2] Human impact on megafauna populations is thought to have been driven by hunting ("overkill") as well as possibly also environmental alteration.[3][4][5] The relative importance of human vs climatic factors in the extinctions has been the subject of long-running controversy.[2]

Major extinctions were incurred in Australia-New Guinea (Sahul) beginning approximately 50,000 years ago and in the Americas about 13,000 years ago, coinciding in time with the early human migrations into these regions.[6][7][8] Extinctions in northern Eurasia were staggered over tens of thousands of years between 50,000 and 10,000 years ago,[1] while extinctions in the Americas were virtually simultaneous, spanning only 3000 years at most.[3][9] Overall, during Late Pleistocene about 65% of all megafaunal species worldwide became extinct,[10] rising to 83% in South America.[9]

Extinctions by biogeographic realm

Summary

| Biogeographic realm | Giants (over 1,000 kg) |

Very large (400–1,000 kg) |

Large (150–400 kg) |

Moderately large (50–150 kg) |

Medium (10–50 kg) |

Total | Regions included | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | Loss | % | Start | Loss | % | Start | Loss | % | Start | Loss | % | Start | Loss | % | start | loss | % | ||

| Afrotropic | 6 | −1 | 16.6% | 4 | −1 | 25% | 25 | −3 | 12% | 32 | 0 | 0% | 69 | −2 | 2.9% | 136 | -7 | 5.1% | Trans-Saharan Africa and Arabia |

| Indomalaya | 5 | −2 | 40% | 6 | −1 | 16.7% | 10 | −1 | 10% | 20 | −3 | 15% | 56 | −1 | 1.8% | 97 | -8 | 8.2% | Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and southern China |

| Palearctic | 8 | −8 | 100% | 10 | −5 | 50% | 14 | −5 | 35.7% | 23 | −3 | 15% | 41 | −1 | 2.4% | 96 | -22 | 22.9% | Eurasia and North Africa |

| Nearctic | 5 | −5 | 100% | 10 | −8 | 80% | 26 | −22 | 84.6% | 20 | −13 | 65% | 25 | −9 | 36% | 86 | -57 | 66% | North America |

| Neotropic | 9 | −9 | 100% | 12 | −12 | 100% | 17 | −14 | 82% | 20 | −11 | 55% | 35 | −5 | 14.3% | 93 | -51 | 54% | South America, Central America, and the Caribbean |

| Australasia | 4 | −4 | 100% | 5 | −5 | 100% | 6 | −6 | 100% | 16 | −13 | 81.2% | 25 | −10 | 40% | 56 | -38 | 67% | Australia , New Guinea, New Zealand, and neighbouring islands. |

| Global | 33 | −26 | 78.8% | 46 | −31 | 67.4% | 86 | −47 | 54.7% | 113 | −41 | 36.3% | 215 | −23 | 10.1% | 493 | -168 | 34% | |

Introduction

The Late Pleistocene saw the extinction of many mammals weighing more than 40 kg. The proportion of megafauna extinctions is progressively larger the further the human migratory distance from Africa, with the highest extinction rates in Australia, and North and South America.

Extinctions in the Americas eliminated all mammals larger than 100 kg of South American origin, including those which migrated north in the Great American Interchange. It was only in Australia and the Americas that extinction occurred at family taxonomic levels or higher. This may relate to non-African megafauna and Homo sapiens not having evolved as species alongside each other. These continents had no known native species of Hominoidea (apes) at all, so no species of Hominidae (greater apes) or Homo.

The increased extent of extinction mirrors the migration pattern of modern humans: the further away from Africa, the more recently humans inhabited the area, the less time those environments (including its megafauna) had to become accustomed to humans (and vice versa).

There is no evidence of megafaunal extinctions at the height of the Last Glacial Maximum, suggesting that increased cold and glaciation were not factors in the Pleistocene extinction.[12]

There are three main hypotheses to explain this extinction:

- climate change associated with the advance and retreat of major ice caps or ice sheets.

- "prehistoric overkill hypothesis"[13]

- the extinction of the woolly mammoth allowed the extensive grassland to become birch forest, then subsequent forest fires changed the climate.[14]

There are some inconsistencies between the current available data and the prehistoric overkill hypothesis. For instance, there are ambiguities around the timing of sudden Australian megafauna extinctions.[13] Evidence supporting the prehistoric overkill hypothesis includes the persistence of megafauna on some islands for millennia past the disappearance of their continental cousins. For instance, ground sloths survived on the Antilles long after North and South American ground sloths were extinct, woolly mammoths died out on remote Wrangel Island 1,000 years after their extinction on the mainland, while Steller's sea cows persisted off the isolated and uninhabited Commander Islands for thousands of years after they had vanished from the continental shores of the north Pacific.[15] The later disappearance of these island species correlates with the later colonization of these islands by humans.

The original debates as to whether human arrival times or climate change constituted the primary cause of megafaunal extinctions necessarily were based on paleontological evidence coupled with geological dating techniques. Recently, genetic analyses of surviving megafaunal populations have contributed new evidence, leading to the conclusion: "The inability of climate to predict the observed population decline of megafauna, especially during the past 75,000 years, implies that human impact became the main driver of megafauna dynamics around this date."[16]

Alternative hypotheses to the theory of human responsibility include climate change associated with the last glacial period, and the Younger Dryas impact hypothesis[17] as well as Tollmann's hypothesis that extinctions resulted from bolide impacts.

Recent research indicates that each species responded differently to environmental changes, and no one factor by itself explains the large variety of extinctions. The causes may involve the interplay of climate change, competition between species, unstable population dynamics, and human predation.[18]

Africa

Although Africa was one least affected regions, the region still suffered extinctions, particularly around the Late Pleistocene-Holocene transition. These extinctions were likely predominantly climatically driven by changes to grassland habitats.[19]

- Ungulates

- Even-Toed Ungulates

- Odd-toed Ungulates

- Rhinoceros (Rhinocerotidae).

- Stephanorhinus hemitoechus (Africa)

- Wild Equus spp.

- Equus algericus

- Equus melkiensis

- Zebras

- Equus capensis

- Saharan zebra[20] (Equus mauritanicus)

- Rhinoceros (Rhinocerotidae).

- Proboscidea

- Elephantidae (elephants)

- Palaeoloxodon iolensis? (other authors suggest that this taxon went extinct at the end of the Middle Pleistocene)

- Elephantidae (elephants)

South, Southeast and Eastern Asia

The timing of extinctions on the Indian subcontinent is uncertain due to a lack of reliable dating.[21] Similar issues have been reported for Chinese sites, though there is no evidence for any of the megafaunal taxa having survived into the Holocene in that region.[22] Extinctions in Southeast Asia and South China have been proposed to be the result of environmental shift from open to closed forested habitats.[23]

- Ungulates

- Even-Toed Ungulates

- Several Bovidae spp.

- Bos palaesondaicus (ancestor to the banteng)

- Bison hanaizumiensis[24][25][26]

- Cebu tamaraw (Bubalus cebuensis)

- Bubalus grovesi[27]

- Bubalus wansijocki

- Short-horned water buffalo (Bubalus mephistopheles)

- Cervidae

- Sinomegaceros spp.[28]

- Hippopotamidae

- Several Bovidae spp.

- Odd-toed Ungulates

- Equus spp.

- Giant tapir (Tapirus augustus)

- Even-Toed Ungulates

- Carnivora

- Caniformia

- Arctoidea

- Bears

- Ailuropoda baconi (ancestor to the giant panda)

- Bears

- Arctoidea

- Caniformia

- Afrotheria

- Afroinsectiphilia

- Orycteropodidae/Tubulidentata

- Aardvark (Orycteropus afer; extirpated in South Asia circa 13,000 BCE)[30][31]

- Orycteropodidae/Tubulidentata

- Paenungulata

- Tethytheria

- Proboscideans

- Stegodontidae

- Stegodon spp. (including Stegodon florensis on Flores, Stegodon orientalis in East and Southeast Asia, and Stegodon sp. in the Indian subcontinent)

- Palaeoloxodon spp.

- Palaeoloxodon namadicus (Indian subcontinent, possibly also Southeast Asia)

- Naumann's elephant (Japan)

- Palaeoloxodon huaihoensis (China)

- Stegodontidae

- Proboscideans

- Tethytheria

- Afroinsectiphilia

- Birds

- Japanese flightless duck (Shiriyanetta hasegawai)[32]

- Leptoptilos robustus

- Primates

- Several simian (Simiiformes) spp.

- Pongo weidenreichi

- Various Homo spp.

- Homo erectus

- Homo floresiensis

- Homo luzonensis

- Denisovans (Homo sp.)

- Several simian (Simiiformes) spp.

Europe and northern Asia

The Palearctic realm spans the entirety of the European continent and stretches into northern Asia, through the Caucasus and central Asia to northern China, Siberia and Beringia. During the Late Pleistocene, this region was noted for its great diversity and dynamism of biomes, including the warm climes of the Mediterranean basin, open temperate woodlands, arid plains, mountainous heathland and swampy wetlands, all of which were vulnerable to the severe climatic fluctuations of the interchanges between glacial and interglacials periods (stadials). However, it was the expansive mammoth steppe which was the ecosystem which united and defined this region during the Late Pleistocene.[33] One of the key features of Europe's Late Pleistocene climate was the often drastic turnover of conditions and biota between the numerous stadials, which could set within a century. For example, during glacial periods, the entire North Sea was drained of water to form Doggerland. The final major cold spell occurred from 25,000 BCE to 18,000 BCE and is known as the Last Glacial Maximum, when the Fenno-Scandinavian ice sheet covered much of northern Europe, while the Alpine ice sheet occupied significant parts of central-southern Europe.

Europe and northern Asia, being far colder and drier than today,[34] was largely hegemonized by the mammoth steppe, an ecosystem dominated by palatable high-productivity grasses, herbs and willow shrubs.[34][35] This supported an extensive biota of grassland fauna and stretched eastwards from Spain in the Iberian Peninsula to Yukon in modern-day Canada .[33][34][36][37] The area was populated by many species of grazers which assembled in large herds similar in size to those in Africa today. Populous species which roamed the great grasslands included the woolly mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, Elasmotherium, steppe bison, Pleistocene horse, muskox, Cervalces, reindeer, various antelopes (goat-horned antelope, mongolian gazelle, saiga antelope and twisted-horned antelope) and steppe pika. Carnivores included Eurasian cave lion, scimitar cat, cave hyena, grey wolf, dhole and the Arctic fox.[38][39][40]

At the edges of these large stretches of grassland could be found more shrub-like terrain and dry conifer forest and woodland (akin to forest steppe or taiga). The browsing collective of megafauna included woolly rhinoceros, giant deer, moose, Cervalces, tarpan, aurochs, woodland bison, camels and smaller deer (Siberian roe deer, red deer and Siberian musk deer). Brown bears, wolverines, cave bear, wolves, lynx, leopards and red foxes also inhabited this biome. Tigers were at stages also present, from the edges of eastern Europe around the Black Sea to Beringia. The more mountainous terrain, incorporating montane grassland, subalpine conifer forest, alpine tundra and broken, craggy slopes, was occupied by several species of mountain-going animals like argali, chamois, ibex, mouflon, Red panda, pika, wolves, leopards, Ursus spp. and lynx, with snow leopards, Baikal yak and snow sheep in northern Asia. Arctic tundra, which lined the north of the mammoth steppe, reflected modern ecology with species such as the polar bear, wolf, reindeer and muskox.

Other biomes, although less noted, were significant in contributing to the diversity of fauna in Late Pleistocene Europe. Warmer grasslands such as temperate steppe and Mediterranean savannah hosted Stephanorhinus, European bison, and onager. These biomes also contained an assortment of mammoth steppe fauna, such as saiga antelope, lions, scimitar cats, wolves, Pleistocene horse, steppe bison, twisted-horned antelope, aurochs and camels. Temperate coniferous, deciduous, mixed broadleaf and Mediterranean forest and open woodland accommodated straight-tusked elephants, Praemegaceros, Stephanorhinus, wild boar, bovids such as European bison, tahr and tur, species of Ursus such as the Etruscan bear and smaller deer (Roe deer, red deer, fallow deer and Mediterranean deer) with several mammoth steppe species such as lynx, tarpan, wolves, dholes, moose, giant deer, woodland bison, leopards and aurochs. Woolly rhinoceros and mammoth occasionally resided in these temperate biomes, mixing with predominately temperate fauna to escape harsh glacials.[41][42] In warmer wetlands, European water buffalo and hippopotamus were present. Although these habitats were restricted to micro refugia and to southern Europe and its fringes, being in Iberia, Italy, the Balkans, Ukraine's Black Sea basin, the Caucasus and western Asia, during inter-glacials these biomes had a far more northernly range. For example, hippopotamus inhabited Great Britain and straight-tusked elephant the Netherlands, as recently as 80,000 BCE and 42,000 BCE respectively.[43][44]

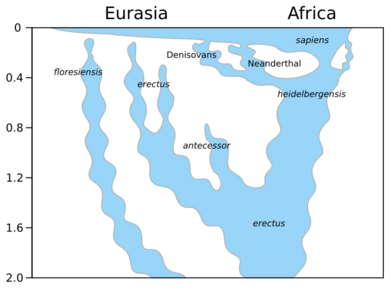

The first possible indications of habitation by hominins are the 7.2 million year old finds of Graecopithecus,[45] and 5.7 million year old footprints in Crete — however established habitation is noted in Georgia from 1.8 million years ago, proceeded to Germany and France, by Homo erectus.[46][47] Prominent co-current and subsequent species include Homo antecessor, Homo cepranensis, Homo heidelbergensis, neanderthals and denisovans,[48] preceding habitation by Homo sapiens circa 38,000 BCE. Extensive contact between African and Eurasian Homo groups is known at least in part through transfers of stone-tool technology in 500,000 BCE and again at 250,000 BCE.[49]

Europe's Late Pleistocene biota went through two phases of extinction. Some fauna became extinct before 13,000 BCE, in staggered intervals, particularly between 50,000 BCE and 30,000 BCE. Species include cave bear, Elasmotherium, straight-tusked elephant, Stephanorhinus, water buffalo, neanderthals, and scimitar cat. However, the great majority of species were extinguished, extirpated or experienced severe population contractions between 13,000 BCE and 9,000 BCE,[50] ending with the Younger Dryas. At that time there were small ice sheets in Scotland and Scandinavia. The mammoth steppe disappeared from the vast majority of its former range, either due to a permanent shift in climatic conditions, or an absence of ecosystem management due to decimated, fragmented or extinct populations of megaherbivores.[51][52] This led to a region wide extinction vortex, resulting in cyclically diminishing bio-productivity[citation needed] and defaunation. Insular species on Mediterranean islands such as Sardinia, Sicily, Malta, Cyprus and Crete, went extinct around the same time as humans colonised those islands. Fauna included dwarf elephants, megacerines and hippopotamuses, and giant avians, otters and rodents.

- Ungulates

- Even-Toed Hoofed Mammals

- Various Bovidae spp.

- Steppe bison (Bison priscus)

- Baikal yak (Bos baikalensis)[38]

- European water buffalo (Bubalus murrensis)

- European tahr (Hemitragus cedrensis)[53][54]

- Giant muskox (Praeovibos priscus)[55]

- Northern saiga antelope (Saiga borealis)[56]

- Twisted-horned antelope (Spirocerus kiakhtensis)[57][39]

- Goat-horned antelope (Parabubalis capricornis)[57][39]

- Various deer (Cervidae) spp.

- Broad-fronted moose (Cervalces latifrons)

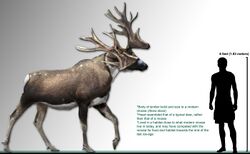

- Giant deer (Megaloceros giganteus)

- Praemegaceros

- Cretan deer (Candiacervus)

- Haploidoceros mediterraneus[58][59]

- All native Hippopotamus spp.[60]

- European hippopotamus (Hippopotamus antiquus)

- Maltese dwarf hippopotamus (Hippopotamus melitensis)

- Cyprus dwarf hippopotamus (Hippopotamus minor)

- Sicilian dwarf hippopotamus (Hippopotamus pentlandi)

- Camelus knoblochi[61] and other Camelus spp.

- Various Bovidae spp.

- Odd-Toed Hoofed Mammals

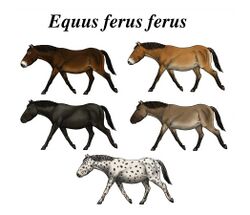

- Various Equus spp. e.g.

- Wild horse (Equus ferus ssp.)

- Equus cf. gallicus[62][63]

- European Ass (Equus hydruntinus)

- Equus cf. latipes[39][62][64]

- Equus cf. lenensis[39][65]

- Equus cf. uralensis[62]

- All native Rhinoceros (Rhinocerotidae) spp.

- Elasmotherium

- Woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis)

- Stephanorhinus spp.

- Merck's rhinoceros (Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis)

- Narrow-nosed rhinoceros (Stephanorhinus hemiotoechus)

- Various Equus spp. e.g.

- Even-Toed Hoofed Mammals

- Carnivora

- Caniformia

- Canidae

- Caninae

- Wolves

- Dholes

- European dhole (Cuon alpinus europaeus)

- Sardinian dhole (Cynotherium sardous)

- Caninae

- Arctoidea

- Various Ursus spp.

- Steppe brown bear (Ursus arctos "priscus")[67]

- Gamssulzen cave bear (Ursus ingressus)[68]

- Pleistocene small cave bear (Ursus rossicus)

- Cave bear (Ursus spelaeus)

- Giant polar bear (Ursus maritimus tyrannus)

- Musteloidea

- Mustelidae

- Several otter (Lutrinae) spp.

- Robust Pleistocene European otter (Cyrnaonyx)

- Algarolutra

- Sardinian giant otter (Megalenhydris barbaricina)

- Sardinian dwarf otter (Sardolutra)

- Cretan otter (Lutrogale cretensis)

- Several otter (Lutrinae) spp.

- Mustelidae

- Various Ursus spp.

- Canidae

- Feliformia

- Various Felidae spp.

- Herpestoidea

- Cave hyena (Crocuta crocuta spelaea)

- Caniformia

- All native Elephant (Elephantidae) spp.

- Mammoths

- Woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius)

- Dwarf Sardinian mammoth (Mammuthus lamarmorai)

- Straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus)

- Dwarf elephant

- Palaeoloxodon creutzburgi

- Cyprus dwarf elephant (Palaeoloxodon cypriotes)

- Palaeoloxodon mnaidriensis

- Mammoths

- Rodents

- Balearic giant dormouse (Hypnomys) spp. e.g.

- Majorcan giant dormouse (Hypnomys morpheus)

- Giant Eurasian porupine (Hystrix refossa)

- Leithia spp. (Maltese and Sicilian giant dormouse)[70]

- Lagomorpha

- Pika (Ochotona) spp. e.g.

- Giant pika (Ochotona whartoni)

- Pika (Ochotona) spp. e.g.

- Eurasian giant beavers (Trogontherium cuiveri)

- Balearic giant dormouse (Hypnomys) spp. e.g.

- Birds

- Asian ostrich (Struthio asiaticus)

- Giant swan (Cygnus falconeri)

- Yakutian goose (Anser djuktaiensis)

- Various European crane spp. (Genus Grus)

- Grus primigenia

- Grus melitensis

- Cretan owl (Athene cretensis)

- Homo

- Denisovans (Homo sp.)

- Neanderthals (Homo (sapiens) neanderthalensis; survived until about 40,000 years ago on the Iberian peninsula)

Many species extant today were present in areas either far to the south or west of their contemporary ranges. For example, all the arctic fauna on this list inhabited regions as south as the Iberian Peninsula at various stages of the Late Pleistocene. Recently extinct organisms are noted as †. Species extirpated from significant portions of or all former ranges in Europe and northern Asia during the Quaternary extinction event include-

- Tiger (Panthera tigris, from the Ukraine Black Sea to Beringia)[71][72][73]

- Cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus)[74][75]

- Leopard (Panthera pardus)

- Snow leopard (Panthera uncia)

- Eurasian and Iberian lynx (Lynx lynx and Lynx pardinus)

- Wolverine (Gulo gulo)

- Polar bear (Ursus maritimus)

- Arctic fox (Vulpes lagopus)

- Dhole (Cuon alpinus)

- Gray wolf (†Megafaunal et Beringian wolf, and the Paleolithic dog (Canis lupus))

- †European Wild Horse (Equus ferus ferus)

- Fallow deer (Dama dama)

- Mouflon (Ovis gmelini)

- Chamois (Rupicapra spp.)

- West Caucasian tur (Capra caucasica)[53][54]

- Saiga antelope (Saiga tatarica)

- Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus)

- Moose (Alces alces)

- Onager (Equus hemionus)

- European bison (Bison bonasus)

- Asian water buffalo (Bubalus arnee)[76]

- Musk ox (Ovibos moschatus)

- Steppe pika (Ochotona pusilla)

- Great jerboa (Allactaga major)

- Hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius)

- Northern bald ibis (Geronticus eremita)

- †Great auk (Pinguinus impennis)[77]

- Snowy owl (Bubo scandiacus)

- Barbary macaque (Macaca sylvanus)

North America

During the last 60,000 years, including the end of the last glacial period, approximately 51 genera of large mammals have become extinct in North America. Of these, many genera extinctions can be reliably attributed to a brief interval of 11,500 to 10,000 radiocarbon years before present, shortly following the arrival of the Clovis people in North America [citation needed]. In contrast, only about half a dozen small mammals disappeared during this time. Most other extinctions are poorly constrained in time, though some definitely occurred outside of this narrow interval.[78] For example, a genetic study published in 2021 indicates that horses, that were directly related to the modern horses, were still present in Yukon at least until 5,700 years ago or mid-Holocene.[79] Previous North American extinction pulses had occurred at the end of glaciations, but not with such an ecological imbalance between large mammals and small ones. Moreover, previous extinction pulses were not comparable to the Quaternary extinction event; they involved primarily species replacements within ecological niches, while the latter event resulted in many ecological niches being left unoccupied. Such include the last native North American terror bird (Titanis), rhinoceros (Aphelops) and hyena (Chasmaporthetes). The extinction also had the effect of increasing homogenisation of large mammal communities between around 15,000 and 10,000 years ago.[80] Human habitation commenced unequivocally approximately 22,000 BCE north of the glacier,[81] and 13,500 BCE south,[82][83] however disputed evidence of southern human habitation exists from 130,000 BCE and 17,000 BCE onwards, described from sites in California and Meadowcroft in Pennsylvania.[84][85] Other prominent paleontological sites documenting human expansion into North America can be found in Mexico[84][86][87][88] and Panama, the crossroads of the American Interchange.[89]

North American extinctions (noted as herbivores (H) or carnivores (C)) included:

- Ungulates

- Even-Toed Hoofed Mammals

- Various Bovidae spp.

- Most forms of Pleistocene bison (only Bison bison in North America, and Bison bonasus in Eurasia, survived)

- Ancient bison (Bison antiquus) (H)

- Long-horned/Giant bison (Bison latifrons) (H)

- Steppe bison (Bison priscus) (H)

- Bison occidentalis (H)

- Wild yak (Bos mutus; extirpated)[90] (H)

- Several members of Caprinae (the muskox survived)

- Giant muskox (Praeovibos priscus) (H)

- Shrub-ox (Euceratherium collinum) (H)

- Harlan's muskox (Bootherium bombifrons) (H)

- Soergel's ox (Soergelia mayfieldi) (H)

- Harrington's mountain goat (Oreamnos harringtoni; smaller and more southern distribution than its surviving relative) (H)

- Saiga antelope (Saiga tatarica; extirpated) (H)

- Most forms of Pleistocene bison (only Bison bison in North America, and Bison bonasus in Eurasia, survived)

- Deer

- Stag-moose (Cervalces scotti) (H)

- American mountain deer (Odocoileus lucasi) (H)

- Torontoceros hypnogeos (H)

- Various Antilocapridae genera (pronghorns survived)

- Capromeryx (H)

- Stockoceros (H)

- Tetrameryx (H)

- Pacific pronghorn (Antilocapra pacifica) (H)

- Several peccary (Tayassuidae) spp.

- Flat-headed peccary (Platygonus) (H)

- Long-nosed peccary (Mylohyus) (H)

- Collared peccary (Dicotyles tajacu; extirpated, range semi-recolonised) (H) (Muknalia minimus is a junior synonym)

- Various members of Camelidae

- Western camel (Camelops hesternus) (H)

- Stilt legged llamas (Hemiauchenia ssp.) (H)

- Stout legged llamas (Palaeolama ssp.) (H)

- Various Bovidae spp.

- Odd-Toed Hoofed Mammals

- All native forms of Equidae

- Equus alaskae (H)

- Equus cedralensis[91] (H)

- Mexican horse (Equus conversidens) (H)

- Equus complicatus[92] (H)

- Equus fraternus (H)

- Giant horse (Equus giganteus) (H)[93]

- Onager (Equus hemionus; extirpated) (H)[94] (H)

- Kiang (Equus kiang; extirpated) (H)[95] (H)

- Yukon horse (Equus lambei) (H)

- Equus mexicanus[91] (H)

- Niobrara horse (Equus niobrarensis) (H)

- Pacific horse (Equus pacificus)[96] (H)

- Western horse (Equus occidentalis) (H)

- Equus semiplicatus (H)

- Hagerman horse / American zebra (Equus simplicidens) (H)

- Scott's horse (Equus scotti) (H)

- Stilt-legged horse (Haringtonhippus francisci / Equus francisci; may be a synonym of Mexican horse) (H)

- All members of North American tapir (Tapirus; four species)

- California tapir (Tapirus californicus) (H)

- Merriam's tapir (Tapirus merriami) (H)

- Vero tapir (Tapirus veroensis) (H)

- All native forms of Equidae

- Mixotoxodon[97][98] (H)

- Even-Toed Hoofed Mammals

- Carnivora

- Feliformia

- Several Felidae spp.

- Saber-Tooths

- North American saber-toothed cat (Smilodon fatalis) (C)

- North American scimitar cat (Homotherium serum) (C)

- American cheetah (Miracinonyx; not true cheetah)

- Miracinonyx inexpectatus (C)

- Miracinonyx trumani (C)

- Cougar (Puma concolor; megafaunal ecomorph extirpated from North America, South American populations recolonised former range) (C)

- Jaguarundi (Herpailurus yagouaroundi; extirpated, range semi-recolonised) (C)

- Margay (Leopardus weidii; extirpated) (C)

- Ocelot (Leopardus pardalis; extirpated, range marginally recolonised) (C)

- Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx; extirpated)[99] (C)

- Jaguars

- Pleistocene North American jaguar (Panthera onca augusta; range semi-recolonised by other subspecies) (C)

- North America Jaguar

- Lions

- American lion (Panthera atrox; endemic to North America after 340,000 BP) (C)

- Eurasian cave lion (Panthera spelaea; present only as far as modern day Yukon) (C)

- Saber-Tooths

- Steppe polecat (Mustela eversmanii; extirpated)[100] (C)

- Several Felidae spp.

- Caniformia

- Canidae

- Dire wolf (Aenocyon dirus) (C)

- Pleistocene coyote (Canis latrans orcutti) (C)

- Megafaunal wolf e.g.

- Beringian wolf (Canis lupus ssp.) (C)

- Dhole (Cuon alpinus; extirpated) (C)

- Protocyon troglodytes[101] (C)

- Arctoidea

- Musteloidea

- Mephitidae

- Short-faced skunk (Brachyprotoma obtusata)[102] (C)

- Mephitidae

- Various bear (Ursidae) spp.

- Arctodus simus (C)

- Florida spectacled bear (Tremarctos floridanus) (C)

- South American short-faced bear (Arctotherium wingei)[84][101] (C)

- Giant polar bear (Ursus maritimus tyrannus; a possible inhabitant) (C)

- Musteloidea

- Canidae

- Feliformia

- Afrotheria

- Afroinsectiphilia

- Orycteropodidae/Tubulidentata

- Giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla; extirpated, range partially recolonised)[103][104] (C)

- Orycteropodidae/Tubulidentata

- Paenungulata

- Tethytheria

- All native spp. of Proboscidea

- Mastodons

- American mastodon (Mammut americanum) (H)

- Pacific mastodon (Mammut pacificus) (H)

- Gomphotheriidae spp.

- Cuvieronius[105] (H)

- Stegomastodon[106] (H)

- Mammoth (Mammuthus) spp.

- Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) (H)

- Pygmy mammoth (Mammuthus exilis) (H)

- Woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) (H)

- Mastodons

- Sirenia

- Dugongidae

- Steller's sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas; extirpated in North America) (H)

- Dugongidae

- All native spp. of Proboscidea

- Tethytheria

- Afroinsectiphilia

- Euarchontoglires

- Bats

- Stock's vampire bat (Desmodus stocki) (C)

- Pristine mustached bat (Pteronotus (Phyllodia) pristinus) (C)

- Rodents

- Giant beaver (Castoroides) spp.

- Klein's porcupine (Erethizon kleini)[107] (H)

- Giant island deer mouse (Peromyscus nesodytes) (C)

- Neochoerus spp. e.g.

- Pinckney's capybara (Neochoerus pinckneyi) (H)

- Neochoerus aesopi (H)

- All giant hutia (Heptaxodontidae) spp.

- Blunt-toothed giant hutia (Amblyrhiza inundata; could grow as large as an American black bear) (H)

- Plate-toothed giant hutia (Elasmodontomys obliquus) (H)

- Twisted-toothed mouse (Quemisia gravis) (H)

- Osborn's key mouse (Clidomys osborn's) (H)

- Xaymaca fulvopulvis (H)

- Lagomorphs

- Aztlan rabbit (Aztlanolagus sp.) (H)

- Giant pika (Ochotona whartoni) (H)

- Bats

- Xenarthrana

- All remaining ground sloth spp.

- Eremotherium (megatheriid giant ground sloth) (H)

- Nothrotheriops (nothrotheriid ground sloth) (H)

- Megalonychid ground sloth spp.

- Megalonyx (H)

- Nohochichak[108][109] (H)

- Xibalbaonyx[110][111] (H)

- Meizonyx

- Megalocnid Greater Antillean dwarf ground sloth spp. (some were probably at least partly arboreal)

- Acratocnus (H)

- Habanocnus (H)

- Megalocnus (H)

- Miocnus (H)

- Neocnus (H)

- Mylodontid ground sloth spp.

- Paramylodon (H)

- Glossotherium (H)

- All members of Glyptodontidae

- Glyptotherium[112] (H)

- Pachyarmatherium (H)

- Beautiful armadillo (Dasypus bellus)[113] (H)

- All Pampatheriidae spp.

- Holmesina (H)

- Pampatherium (H)

- All remaining ground sloth spp.

- Birds

- Water Fowl

- Ducks

- Bermuda flightless duck (Anas pachyscelus) (H)

- Californian flightless sea duck (Chendytes lawi) (C)

- Mexican stiff-tailed duck (Oxyura zapatima)[84] (H)

- Ducks

- Turkey (Meleagris) spp.

- Californian turkey (Meleagris californica) (H)

- Meleagris crassipes[84] (H)

- Various Gruiformes spp.

- All cave rail (Nesotrochis) spp. e.g.

- Antillean cave rail (Nesotrochis debooyi) (C)

- Barbados rail (Incertae sedis) (C)

- Cuban flightless crane (Antigone cubensis) (H)

- La Brea crane (Grus pagei) (H)

- All cave rail (Nesotrochis) spp. e.g.

- Various flamingo (Phoenicopteridae) spp.

- Minute flamingo (Phoenicopterus minutus)[114] (C)

- Cope's flamingo (Phoenicopterus copei)[115] (C)

- Dow's puffin (Fratercula dowi) (C)

- Pleistocene Mexican diver spp.

- Storks

- La Brea/Asphalt stork (Ciconia maltha)[84] (C)

- Wetmore's stork (Mycteria wetmorei)[84] (C)

- Pleistocene Mexican cormorants spp. (genus Phalacrocorax)[84]

- Phalacrocorax goletensis (C)

- Phalacrocorax chapalensis (C)

- All remaining teratorn (Teratornithidae) spp.

- Several New World vultures (Cathartidae) spp.

- Pleistocene black vulture (Coragyps occidentalis ssp.) (C)

- Megafaunal Californian condor (Gymnogyps amplus) (C)

- Clark's condor (Breagyps clarki) (C)

- Cuban condor (Gymnogyps varonai) (C)

- Several Accipitridae spp.

- American neophrone vulture (Neophrontops americanus)[84][116] (C)

- Woodward's eagle (Amplibuteo woodwardi) (C)

- Cuban great hawk (Buteogallus borrasi) (C)

- Daggett's eagle (Buteogallus daggetti) (C)

- Fragile eagle (Buteogallus fragilis) (C)

- Cuban giant hawk (Gigantohierax suarezi)[117][118] (C)

- Errant eagle (Neogyps errans) (C)

- Grinnell's crested eagle (Spizaetus grinnelli)[84] (C)

- Willett's hawk-eagle (Spizaetus willetti)[84] (C)

- Caribbean titan hawk (Titanohierax) (C)

- Several owl (Strigiformes) spp.

- Brea miniature owl (Asphaltoglaux) (C)

- Kurochkin's pygmy owl (Glaucidium kurochkini) (C)

- Brea owl (Oraristix brea) (C)

- Cuban giant owl (Ornimegalonyx) (C)

- Bermuda flicker (Colaptes oceanicus) (C)

- Several caracara (Caracarinae) spp.

- Bahaman terrestrial caracara (Caracara sp.) (C)

- Puerto Rican terrestrial caracara (Caracara sp.) (C)

- Jamaican caracara (Carcara tellustris) (C)

- Cuban caracara (Milvago sp.) (C)

- Hispaniolan caracara (Milvago sp.) (C)

- Psittacopasserae

- Psittaciformes

- Mexican thick-billed parrot (Rhynchopsitta phillipsi)[84] (H)

- Psittaciformes

- Water Fowl

- Several giant tortoise spp.

- Hesperotestudo (H)

- Gopherus spp.

- Gopherus donlaloi (H)

- Chelonoidis spp.

- Chelonoidis marcanoi (H)

- Chelonoidis alburyorum (H)

The survivors are in some ways as significant as the losses: bison (H), grey wolf (C), lynx (C), grizzly bear (C), American black bear (C), deer (e.g. caribou, moose, wapiti (elk), Odocoileus spp.) (H), pronghorn (H), white-lipped peccary (H), muskox (H), bighorn sheep (H), and mountain goat (H); the list of survivors also include species which were extirpated during the Quaternary extinction event, but recolonised at least part of their ranges during the mid-holocene from South American relict populations, such as the cougar (C), jaguar (C), giant anteater (C), collared peccary (H), ocelot (C) and jaguarundi (C). All save the pronghorns and giant anteaters were descended from Asian ancestors that had evolved with human predators.[119] Pronghorns are the second-fastest land mammal (after the cheetah), which may have helped them elude hunters. More difficult to explain in the context of overkill is the survival of bison, since these animals first appeared in North America less than 240,000 years ago and so were geographically removed from human predators for a sizeable period of time.[120][121][122] Because ancient bison evolved into living bison,[123][124] there was no continent-wide extinction of bison at the end of the Pleistocene (although the genus was regionally extirpated in many areas). The survival of bison into the Holocene and recent times is therefore inconsistent with the overkill scenario. By the end of the Pleistocene, when humans first entered North America, these large animals had been geographically separated from intensive human hunting for more than 200,000 years. Given this enormous span of geologic time, bison would almost certainly have been very nearly as naive as native North American large mammals.

The culture that has been connected with the wave of extinctions in North America is the paleo-American culture associated with the Clovis people (q.v.), who were thought to use spear throwers to kill large animals. The chief criticism of the "prehistoric overkill hypothesis" has been that the human population at the time was too small and/or not sufficiently widespread geographically to have been capable of such ecologically significant impacts. This criticism does not mean that climate change scenarios explaining the extinction are automatically to be preferred by default, however, any more than weaknesses in climate change arguments can be taken as supporting overkill. Some form of a combination of both factors could be plausible, and overkill would be a lot easier to achieve large-scale extinction with an already stressed population due to climate change.

South America

The Neotropical realm was affected by the fact that South America had been isolated as an island continent for many millions of years, and had a wide range of fauna found nowhere else, although many of them became extinct during the Great American Interchange about 3 million years ago, such as the Sparassodonta family. Those that survived the interchange included the ground sloths, glyptodonts, litopterns, pampatheres, phorusrhacids (terror birds) and notoungulates; all managed to extend their range to North America.[125][126][127] In the Pleistocene, South America remained largely unglaciated except for increased mountain glaciation in the Andes, which had a two-fold effect- there was a faunal divide between the Andes,[128][129] and the colder, arid interior resulted in the advance of temperate lowland woodland, tropical savanna and desert at the expense of rainforest.[130][131][132][133][134] Within these open environments, megafauna diversity was extremely dense, with over 40 genera recorded from the Guerrero member of Luján Formation alone.[135][136][137][138] Ultimately, by the mid-Holocene, all the preeminent genera of megafauna became extinct- the last specimens of Doedicurus and Toxodon have been dated to 4,555 BCE and 3,000 BCE respectively.[139][140][141][130] Their smaller relatives remain, including anteaters, tree sloths, armadillos; New World marsupials: opossums, shrew opossums, and the monito del monte (actually more related to Australian marsupials).[142] Intense human habitation was established circa 11,000 BCE, however partly disputed evidence of pre-clovis habitation occurs since 46,000 BCE and 20,000 BCE, such as at the Serra da Capivara National Park (Brazil) and Monte Verde (Chile) sites.[84][83][143] Today the largest land mammals remaining in South America are the wild camels of the Lamini group, such as the guanacos and vicuñas, and the genus Tapirus, of which Baird's tapir can reach up to 400 kg. Other notable surviving large fauna are peccaries, marsh deer (Capreolinae), giant anteaters, spectacled bears, maned wolves, pumas, ocelots, jaguars, rheas, emerald tree boas, boa constrictors, anacondas, American crocodiles, caimans, and giant rodents such as capybaras.

- Ungulates

- Even-Toed Hoofed Mammals

- Several Cervidae spp.

- Morenelaphus

- Antifer

- Agalmaceros blicki[144][145]

- Odocoileus salinae[146][139]

- Various Camelidae spp.

- Eulamaops

- Stilt legged llama Hemiauchenia

- Stout legged llama Palaeolama

- Several Cervidae spp.

- Odd-Toed Hoofed Mammals

- All remaining Meridiungulata genera

- Litopterna spp.

- Macrauchenia

- Macraucheniopsis[149][150]

- Proterotheriidae spp. e.g.

- Xenorhinotherium

- Notoungulata spp.

- Litopterna spp.

- Even-Toed Hoofed Mammals

- Carnivora

- Feliformia

- Several Felidae spp.

- Saber-toothed cat (Smilodon) spp.[128]

- North American saber-toothed cat (Smilodon fatalis)

- South American saber-toothed cat (Smilodon populator)

- Pleistocene South American jaguar (Panthera onca mesembrina)

- Saber-toothed cat (Smilodon) spp.[128]

- Several Felidae spp.

- Caniformia

- Canidae

- Dire wolf (Aenocyon dirus)

- Nehring's wolf (Canis nehringi)

- Protocyon spp.[152]

- Protocyon trogolodytes

- Protocyon tarijense

- Dusicyon avus

- Pleistocene bush dog (Speothos pacivorus)

- Arctoidea

- South American short-faced bear (Arctotherium spp.)

- Arctotherium bonairense

- Arctotherium tarijense

- Arctotherium wingei

- South American short-faced bear (Arctotherium spp.)

- Canidae

- Feliformia

- Rodents

- Giant vampire bat (Desmodus draculae)

- Neochoerus

- All remaining Gomphotheridae spp.

- Xenarthrans

- All remaining ground sloth genera

- All remaining Glyptodontinae spp.

- Several Dasypodidae spp.

- Beautiful armadillo (Dasypus bellus)

- Eutatus

- Pachyarmatherium

- Propaopus[60][139]

- All Pampatheriidae spp.

- Holmesina (et 'Chlamytherium occidentale')[161][162]

- Pampatherium[163]

- Tonnicinctus[163]

- Birds

- Psilopterus (small terror bird remains dated to the Late Pleistocene,[164][165] but these are disputed)[166]

- Various Caracarinae spp.

- Various Cathartidae spp.

- Pampagyps imperator

- Geronogyps reliquus

- Wingegyps cartellei

- Pleistovultur nevesi

- Crocs & Gators

- Caiman venezuelensis

- Chelonoidis lutzae (Argentina)

The Pacific (Australasia and Oceania)

There exists two hypotheses regarding the extinction of the Australian megafauna, the first being that they went extinct with the arrival of the Aboriginal Australians on the continent, while he second hypothesis is that the Australian megafauna went extinct due to natural climate change. The main reason this theory exists is that there is evidence of megafauna surviving up until 40,000 years ago, a full 30,000 years after homo sapiens first landed in Australia. Implying that there was a significant period of homo sapiens and megafauna coexistence. Evidence of these animals existing at this time come from fossils records and ocean sediment. To begin with, sediment core drilled in the Indian Ocean off the coast of the southwest Australia indicate the existence of a fungus called Sporormiella which survived off the dung of plant eating mammals. The abundance of these spores in the sediment prior to 45,000 years ago indicates a lot of large mammals existed on the southwest Australian landscape up until that point. The sediment data also indicated that the megafauna population collapsed within a few thousand years around the 45,000 years ago suggesting a rapid extinction event.[170] In addition, fossils found at South Walker Creek, which is the youngest megafauna site in northern Australia, indicate that at least 16 species of megafauna survived there up until 40,000 years ago. Furthermore, there is no firm evidence of homo sapiens beings at South Walker Creek 40,000 years ago, therefore no human cause can be attributed to the extinction of these megafauna. However, there is evidence of major environmental deterioration of South Water Creek 40,000 years ago which the extinction can be attributed to. These changes include increased fire, reduction in grasslands, and the loss of freshwater.[171] The same environmental deterioration is seen across Australia at the time further strengthening the climate change argument. Australia’s climate at the time could best be described as an overall drying of the landscape due to less mean annual precipitation causing less freshwater availability and more drought conditions across the landscape. Overall, this led to changes in vegetation, increased fires, overall reduction in grasslands, and a greater competition for already scarce amount of freshwater.[172] In turn all these environmental changes proved to be too much for the Australian megafauna to cope with causing 90% of megafauna species to go extinct.

The third hypothesis shared by some scientists is that human impacts and natural climate changes led to the extinction of Australian megafauna. To begin with it is important to note that approximately 75% of Australia is semi-arid or arid landscape, therefore it makes sense that megafauna species utilized the same freshwater resources as humans. As a result, this could have increased the amount of megafauna hunted due to the competition for freshwater as the drought conditions persisted.[173] On top of the already dry conditions and diminishing grasslands, homo sapiens used fire agriculture to burn impassable land. This further diminished the already disappearing grassland which contained plants that were key dietary component of herbivorous megafauna. While there is no scientific consensus on the true cause of the extinction of Australian megafauna it is plausible that homo sapiens and natural climate change both had an impact because they were both in Australia at the time. Overall, there is an immense amount of evidence pointing to humans being the culprit but by ruling out climate change completely as a cause of the Australian megafauna extinction we are not getting the whole picture. The climate change that occurred in Australia 45,000 years ago destabilized the ecosystem making it particularly vulnerable to hunting and fire agriculture by humans; this is probably what led to the extinction of the Australian megafauna.

In Sahul (a former continent composed of Australia and New Guinea), the sudden and extensive spate of extinctions occurred earlier than in the rest of the world.[174][175][176][177][178] Most evidence points to a 20,000 year period after human arrival circa 63,000 BCE,[179] but scientific argument continues as to the exact date range.[180] In the rest of the Pacific (other Australasian islands such as New Caledonia, and Oceania) although in some respects far later, endemic fauna also usually perished quickly upon the arrival of humans in the late Pleistocene and early Holocene. This section does only include extinctions that took place prior to European discovery of the respective islands.

- Marsupials

- Various members of Diprotodontidae

- Diprotodon

- Hulitherium tomasetti

- Maokopia ronaldi

- Zygomaturus

- Palorchestes ("marsupial tapir")

- Various members of Vombatidae

- Lasiorhinus angustidens (giant wombat)

- Phascolonus (giant wombat)

- Ramasayia magna (giant wombat)

- Vombatus hacketti (Hackett's wombat)

- Warendja wakefieldi (dwarf wombat)

- Sedophascolomys (giant wombat)

- Phascolarctos stirtoni (giant koala)

- Marsupial lion (Thylacoleo carnifex)

- Various members of Macropodidae

- Procoptodon (short-faced kangaroos) e.g.

- Procoptodon goliah

- Sthenurus (giant kangaroo)

- Simosthenurus (giant kangaroo)

- Various Macropus (giant kangaroo) spp. e.g.

- Protemnodon (giant wallaby)

- Troposodon (wallaby)[175][176][181][182][183][184]

- Bohra (giant tree kangaroo)

- Propleopus oscillans (omnivorous, giant musky rat-kangaroo)

- Nombe

- Congruus

- Procoptodon (short-faced kangaroos) e.g.

- Thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus; extirpated on mainland Australia and New Guinea)

- Various forms of Sarcophilus (Tasmanian devil)

- Sarcophilus laniarius (25% larger than modern species)

- Sarcophilus moornaensis

- Sarcophilus harrisii (extirpated on mainland Australia)

- Various members of Diprotodontidae

- Monotremes: egg-laying mammals.

- Echidna

- Murrayglossus hacketti (giant echidna)

- Megalibgwilia ramsayi

- Echidna

- Birds

- Pygmy Cassowary (Casuarius lydekkeri)

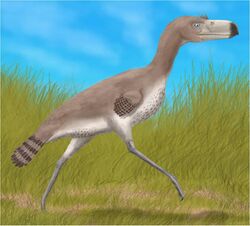

- Genyornis (a two-meter-tall (6.6 ft) dromornithid

- Tasmanian nativehen (Tribonyx mortierii; extirpated on mainland Australia)

- Giant malleefowl (Progura gallinacea)

- Cryptogyps lacertosus

- Dynatoaetus gaffae

- Several Phoenicopteridae spp.

- Xenorhynchopsis spp. (Australian flamingo)[185]

- Xenorhynchopsis minor

- Xenorhynchopsis tibialis

- Reptiles

- Crocs & Gators

- Ikanogavialis (the last fully marine crocodilian)

- Pallimnarchus (Australian freshwater mekosuchine crocodiian)

- Quinkana (Australian terrestrial mekosuchine crocodilian, apex predator)

- Volia (a two-to-three meter long mekosuchine crocodylian, apex predator of Pleistocene Fiji)

- Varanus sp. (Pleistocene and Holocene New Caledonia)

- Snakes

- Wonambi (a five-to-six-metre-long Australian constrictor snake)

- Megalania (Varanus pricus) (a giant predatory monitor lizard)

- Several spp. of Meiolaniidae (giant armoured turtles)

- Crocs & Gators

Relationship to later extinctions

There is no general agreement on where the Holocene, or anthropogenic, extinction begins, and the Quaternary extinction event ends, or if they should be considered separate events at all.[186][187] Some have suggested that anthropogenic extinctions may have begun as early as when the first modern humans spread out of Africa between 100,000 and 200,000 years ago, which is supported by rapid megafaunal extinction following recent human colonisation in Australia, New Zealand and Madagascar,[188] in a similar way that any large, adaptable predator moving into a new ecosystem would. In many cases, it is suggested even minimal hunting pressure was enough to wipe out large fauna, particularly on geographically isolated islands.[189][190] Only during the most recent parts of the extinction have plants also suffered large losses.[191]

Overall, the Holocene extinction can be characterised by the human impact on the environment. The Holocene extinction continues into the 21st century, with overfishing, ocean acidification and the amphibian crisis being a few broader examples of an almost universal, cosmopolitan decline of biodiversity.

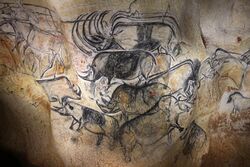

Hunting hypothesis

The hunting hypothesis suggests that humans hunted megaherbivores to extinction, which in turn caused the extinction of carnivores and scavengers which had preyed upon those animals.[192][193][194] This hypothesis holds Pleistocene humans responsible for the megafaunal extinction. One variant, known as blitzkrieg, portrays this process as relatively quick. Some of the direct evidence for this includes: fossils of some megafauna found in conjunction with human remains, embedded arrows and tool cut marks found in megafaunal bones, and European cave paintings that depict such hunting. Biogeographical evidence is also suggestive: the areas of the world where humans evolved currently have more of their Pleistocene megafaunal diversity (the elephants and rhinos of Asia and Africa) compared to other areas such as Australia , the Americas, Madagascar and New Zealand without the earliest humans.

Circumstantially, the close correlation in time between the appearance of humans in an area and extinction there provides weight for this scenario. The megafaunal extinctions covered a vast period of time and highly variable climatic situations. The earliest extinctions in Australia were complete approximately 50,000 BP, well before the last glacial maximum and before rises in temperature. The most recent extinction in New Zealand was complete no earlier than 500 BP and during a period of cooling. In between these extremes megafaunal extinctions have occurred progressively in such places as North America, South America and Madagascar with no climatic commonality. The only common factor that can be ascertained is the arrival of humans.[195][196] This phenomenon appears even within regions. The mammal extinction wave in Australia about 50,000 years ago coincides not with known climatic changes, but with the arrival of humans. In addition, large mammal species like the giant kangaroo Protemnodon appear to have succumbed sooner on the Australian mainland than on Tasmania, which was colonised by humans a few thousand years later.[197][198]

Extinction through human hunting has been supported by archaeological finds of mammoths with projectile points embedded in their skeletons, by observations of modern naive animals allowing hunters to approach easily[199][200][201] and by computer models by Mosimann and Martin,[202] and Whittington and Dyke,[203] and most recently by Alroy.[204]

A study published in 2015 supported the hypothesis further by running several thousand scenarios that correlated the time windows in which each species is known to have become extinct with the arrival of humans on different continents or islands.[205] This was compared against climate reconstructions for the last 90,000 years.[205] The researchers found correlations of human spread and species extinction indicating that the human impact was the main cause of the extinction, while climate change exacerbated the frequency of extinctions.[205][206] The study, however, found an apparently low extinction rate in the fossil record of mainland Asia.[206]

Overkill hypothesis

The overkill hypothesis, a variant of the hunting hypothesis, was proposed in 1966 by Paul S. Martin,[207] Professor of Geosciences Emeritus at the Desert Laboratory of the University of Arizona.[208]

Objections to the hunting hypothesis

The major objections to the theory are as follows:

- There is no archeological evidence that in North America megafauna other than mammoths, mastodons, gomphotheres and bison were hunted, despite the fact that, for example, camels and horses are very frequently reported in fossil history.[209] Overkill proponents, however, say this is due to the fast extinction process in North America and the low probability of animals with signs of butchery to be preserved.[210] A study by Surovell and Grund[211] concluded "archaeological sites dating to the time of the coexistence of humans and extinct fauna are rare. Those that preserve bone are considerably more rare, and of those, only a very few show unambiguous evidence of human hunting of any type of prey whatsoever."

- Eugene S. Hunn points out that the birthrate in hunter-gatherer societies is generally too low, that too much effort is involved in the bringing down of a large animal by a hunting party, and that in order for hunter-gatherers to have brought about the extinction of megafauna simply by hunting them to death, an extraordinary amount of meat would have had to have been wasted.[212]

Climate change hypothesis

At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, when scientists first realized that there had been glacial and interglacial ages, and that they were somehow associated with the prevalence or disappearance of certain animals, they surmised that the termination of the Pleistocene ice age might be an explanation for the extinctions.

Critics object that since there were multiple glacial advances and withdrawals in the evolutionary history of many of the megafauna, it is rather implausible that only after the last glacial maximum would there be such extinctions. One study suggests that the Pleistocene megafaunal composition may have differed markedly from that of earlier interglacials, making the Pleistocene populations particularly vulnerable to changes in their environment.[213]

Some evidence weighs against climate change as a valid hypothesis as applied to Australia. It has been shown that the prevailing climate at the time of extinction (40,000–50,000 BP) was similar to that of today, and that the extinct animals were strongly adapted to an arid climate. The evidence indicates that all of the extinctions took place in the same short time period, which was the time when humans entered the landscape. The main mechanism for extinction was probably fire (started by humans) in a then much less fire-adapted landscape. Isotopic evidence shows sudden changes in the diet of surviving species, which could correspond to the stress they experienced before extinction.[214][215][216]

Evidence in Southeast Asia, in contrast to Europe, Australia, and the Americas, suggests that climate change and an increasing sea level were significant factors in the extinction of several herbivorous species. Alterations in vegetation growth and new access routes for early humans and mammals to previously isolated, localized ecosystems were detrimental to select groups of fauna.[217]

Some evidence obtained from analysis of the tusks of mastodons from the American Great Lakes region appears inconsistent with the climate change hypothesis. Over a span of several thousand years prior to their extinction in the area, the mastodons show a trend of declining age at maturation. This is the opposite of what one would expect if they were experiencing stresses from deteriorating environmental conditions, but is consistent with a reduction in intraspecific competition that would result from a population being reduced by human hunting.[218]

Increased temperature

The most obvious change associated with the termination of an ice age is the increase in temperature. Between 15,000 BP and 10,000 BP, a 6 °C increase in global mean annual temperatures occurred. This was generally thought to be the cause of the extinctions.

According to this hypothesis, a temperature increase sufficient to melt the Wisconsin ice sheet could have placed enough thermal stress on cold-adapted mammals to cause them to die. Their heavy fur, which helps conserve body heat in the glacial cold, might have prevented the dumping of excess heat, causing the mammals to die of heat exhaustion. Large mammals, with their reduced surface area-to-volume ratio, would have fared worse than small mammals.

A study covering the past 56,000 years indicates that rapid warming events with temperature changes of up to 16 °C (29 °F) had an important impact on the extinction of megafauna. Ancient DNA and radiocarbon data indicates that local genetic populations were replaced by others within the same species or by others within the same genus. Survival of populations was dependent on the existence of refugia and long distance dispersals, which may have been disrupted by human hunters.[219]

Arguments against the temperature hypothesis

Studies propose that the annual mean temperature of the current interglacial that we have seen for the last 10,000 years is no higher than that of previous interglacials, yet most of the same large mammals survived similar temperature increases.[220][221][222][223][224][225]

In addition, numerous species such as mammoths on Wrangel Island[226] and St. Paul Island survived in human-free refugia despite changes in climate. This would not be expected if climate change were responsible (unless their maritime climates offered some protection against climate change not afforded to coastal populations on the mainland). Under normal ecological assumptions island populations should be more vulnerable to extinction due to climate change because of small populations and an inability to migrate to more favorable climes.[citation needed]

Increased continentality affects vegetation in time or space

Other scientists have proposed that increasingly extreme weather—hotter summers and colder winters—referred to as "continentality", or related changes in rainfall caused the extinctions. The various hypotheses are outlined below.

Vegetation changes: geographic

It has been shown that vegetation changed from mixed woodland-parkland to separate prairie and woodland.[222][223][225] This may have affected the kinds of food available. Shorter growing seasons may have caused the extinction of large herbivores and the dwarfing of many others. In this case, as observed, bison and other large ruminants would have fared better than horses, elephants and other monogastrics, because ruminants are able to extract more nutrition from limited quantities of high-fiber food and better able to deal with anti-herbivory toxins.[227][228][229] So, in general, when vegetation becomes more specialized, herbivores with less diet flexibility may be less able to find the mix of vegetation they need to sustain life and reproduce, within a given area.

Rainfall changes: time

Increased continentality resulted in reduced and less predictable rainfall limiting the availability of plants necessary for energy and nutrition.[230][231][232] Axelrod[233] and Slaughter[234] have suggested that this change in rainfall restricted the amount of time favorable for reproduction. This could disproportionately harm large animals, since they have longer, more inflexible mating periods, and so may have produced young at unfavorable seasons (i.e., when sufficient food, water, or shelter was unavailable because of shifts in the growing season). In contrast, small mammals, with their shorter life cycles, shorter reproductive cycles, and shorter gestation periods, could have adjusted to the increased unpredictability of the climate, both as individuals and as species which allowed them to synchronize their reproductive efforts with conditions favorable for offspring survival. If so, smaller mammals would have lost fewer offspring and would have been better able to repeat the reproductive effort when circumstances once more favored offspring survival.[235]

In 2017 a study looked at the environmental conditions across Europe, Siberia and the Americas from 25,000–10,000 YBP. The study found that prolonged warming events leading to deglaciation and maximum rainfall occurred just prior to the transformation of the rangelands that supported megaherbivores into widespread wetlands that supported herbivore-resistant plants. The study proposes that moisture-driven environmental change led to the megafaunal extinctions and that Africa's trans-equatorial position allowed rangeland to continue to exist between the deserts and the central forests, therefore fewer megafauna species became extinct there.[219]

Arguments against the continentality hypotheses

Critics have identified a number of problems with the continentality hypotheses.

- Megaherbivores have prospered at other times of continental climate. For example, megaherbivores thrived in Pleistocene Siberia, which had and has a more continental climate than Pleistocene or modern (post-Pleistocene, interglacial) North America.[236][237][238]

- The animals that became extinct actually should have prospered during the shift from mixed woodland-parkland to prairie, because their primary food source, grass, was increasing rather than decreasing.[239][238][240] Although the vegetation did become more spatially specialized, the amount of prairie and grass available increased, which would have been good for horses and for mammoths, and yet they became extinct. This criticism ignores the increased abundance and broad geographic extent of Pleistocene Bison at the end of the Pleistocene, which would have increased competition for these resources in a manner not seen in any earlier interglacials.[213]

- Although horses became extinct in the New World, they were successfully reintroduced by the Spanish in the 16th century—into a modern post-Pleistocene, interglacial climate. Today there are feral horses still living in those same environments. They find a sufficient mix of food to avoid toxins, they extract enough nutrition from forage to reproduce effectively and the timing of their gestation is not an issue. Of course, this criticism ignores the obvious fact that present-day horses are not competing for resources with ground sloths, mammoths, mastodons, camels, llamas, and bison. Similarly, mammoths survived the Pleistocene Holocene transition on isolated, uninhabited islands in the Mediterranean Sea[241] and on Wrangel Island in the Siberian Arctic[242] until 4,000 to 7,000 years ago.

- Large mammals should have been able to migrate, permanently or seasonally, if they found the temperature too extreme, the breeding season too short, or the rainfall too sparse or unpredictable.[243] Seasons vary geographically. By migrating away from the equator, herbivores could have found areas with growing seasons more favorable for finding food and breeding successfully. Modern-day African elephants migrate during periods of drought to places where there is apt to be water.[244]

- Large animals store more fat in their bodies than do medium-sized animals[245] and this should have allowed them to compensate for extreme seasonal fluctuations in food availability.

The extinction of the megafauna could have caused the disappearance of the mammoth steppe. Alaska now has low nutrient soil unable to support bison, mammoths, and horses. R. Dale Guthrie has claimed this as a cause of the extinction of the megafauna there; however, he may be interpreting it backwards. The loss of large herbivores to break up the permafrost allows the cold soils that are unable to support large herbivores today. Today, in the arctic, where trucks have broken the permafrost grasses and diverse flora and fauna can be supported.[246][247] In addition, Chapin (Chapin 1980) showed that simply adding fertilizer to the soil in Alaska could make grasses grow again like they did in the era of the mammoth steppe. Possibly, the extinction of the megafauna and the corresponding loss of dung is what led to low nutrient levels in modern-day soil and therefore is why the landscape can no longer support megafauna.

Arguments against both climate change and overkill

It may be observed that neither the overkill nor the climate change hypotheses can fully explain events: browsers, mixed feeders and non-ruminant grazer species suffered most, while relatively more ruminant grazers survived.[248] However, a broader variation of the overkill hypothesis may predict this, because changes in vegetation wrought by either Second Order Predation (see below)[249][250] or anthropogenic fire preferentially selects against browse species.[citation needed]

Hyperdisease hypothesis

Theory

The hyperdisease hypothesis, as advanced by Ross D. E. MacFee and Preston A. Marx, attributes the extinction of large mammals during the late Pleistocene to indirect effects of the newly arrived aboriginal humans.[251][252][253] The hyperdisease hypothesis proposes that humans or animals traveling with them (e.g., chickens or domestic dogs) introduced one or more highly virulent diseases into vulnerable populations of native mammals, eventually causing extinctions. The extinction was biased toward larger-sized species because smaller species have greater resilience because of their life history traits (e.g., shorter gestation time, greater population sizes, etc.). Humans are thought to be the cause because other earlier immigrations of mammals into North America from Eurasia did not cause extinctions.[251]

Diseases imported by people have been responsible for extinctions in the recent past; for example, bringing avian malaria to Hawaii has had a major impact on the isolated birds of the island.

If a disease was indeed responsible for the end-Pleistocene extinctions, then there are several criteria it must satisfy (see Table 7.3 in MacPhee & Marx 1997). First, the pathogen must have a stable carrier state in a reservoir species. That is, it must be able to sustain itself in the environment when there are no susceptible hosts available to infect. Second, the pathogen must have a high infection rate, such that it is able to infect virtually all individuals of all ages and sexes encountered. Third, it must be extremely lethal, with a mortality rate of c. 50–75%. Finally, it must have the ability to infect multiple host species without posing a serious threat to humans. Humans may be infected, but the disease must not be highly lethal or able to cause an epidemic.[citation needed]

One suggestion is that pathogens were transmitted by the expanding humans via the domesticated dogs they brought with them,[254] though this does not fit the timeline of extinctions in the Americas and Australia in particular.

Arguments against the hyperdisease hypothesis

- Generally speaking, disease has to be very virulent to kill off all the individuals in a genus or species. Even such a virulent disease as West Nile fever is unlikely to have caused extinction.[255]

- The disease would need to be implausibly selective while being simultaneously implausibly broad. Such a disease needs to be capable of killing off wolves such as Canis dirus or goats such as Oreamnos harringtoni while leaving other very similar species (Canis lupus and Oreamnos americanus, respectively) unaffected. It would need to be capable of killing off flightless birds while leaving closely related flighted species unaffected. Yet while remaining sufficiently selective to afflict only individual species within genera it must be capable of fatally infecting across such clades as birds, marsupials, placentals, testudines, and crocodilians. No disease with such a broad scope of fatal infectivity is known, much less one that remains simultaneously incapable of infecting numerous closely related species within those disparate clades. On the other hand, this objection does not account for the possibility of a variety of different diseases being introduced around the same era.[citation needed]

- Numerous species including wolves, mammoths, camelids, and horses had emigrated continually between Asia and North America over the past 100,000 years. For the disease hypothesis to be applicable there it would require that the population remain immunologically naive despite this constant transmission of genetic and pathogenic material.[citation needed]

- The dog-specific hypothesis cannot account for several major extinction events, notably the Americas (for reasons already covered) and Australia. Dogs did not arrive in Australia until approximately 35,000 years after the first humans arrived there, and approximately 30,000 years after the Australian megafaunal extinction was complete.[citation needed]

Second-order predation hypothesis

Scenario

The Second-Order Predation Hypothesis says that as humans entered the New World they continued their policy of killing predators, which had been successful in the Old World but because they were more efficient and because the fauna, both herbivores and carnivores, were more naive, they killed off enough carnivores to upset the ecological balance of the continent, causing overpopulation, environmental exhaustion, and environmental collapse. The hypothesis accounts for changes in animal, plant, and human populations.

The scenario is as follows:

- After the arrival of H. sapiens in the New World, existing predators must share the prey populations with this new predator. Because of this competition, populations of original, or first-order, predators cannot find enough food; they are in direct competition with humans.

- Second-order predation begins as humans begin to kill predators.

- Prey populations are no longer well controlled by predation. Killing of nonhuman predators by H. sapiens reduces their numbers to a point where these predators no longer regulate the size of the prey populations.

- Lack of regulation by first-order predators triggers boom-and-bust cycles in prey populations. Prey populations expand and consequently overgraze and over-browse the land. Soon the environment is no longer able to support them. As a result, many herbivores starve. Species that rely on the slowest recruiting food become extinct, followed by species that cannot extract the maximum benefit from every bit of their food.

- Boom-bust cycles in herbivore populations change the nature of the vegetative environment, with consequent climatic impacts on relative humidity and continentality. Through overgrazing and overbrowsing, mixed parkland becomes grassland, and climatic continentality increases.

Support

This has been supported by a computer model, the Pleistocene extinction model (PEM), which, using the same assumptions and values for all variables (herbivore population, herbivore recruitment rates, food needed per human, herbivore hunting rates, etc.) other than those for hunting of predators. It compares the overkill hypothesis (predator hunting = 0) with second-order predation (predator hunting varied between 0.01 and 0.05 for different runs). The findings are that second-order predation is more consistent with extinction than is overkill[256][257] (results graph at left).

The Pleistocene extinction model is the only test of multiple hypotheses and is the only model to specifically test combination hypotheses by artificially introducing sufficient climate change to cause extinction. When overkill and climate change are combined they balance each other out. Climate change reduces the number of plants, overkill removes animals, therefore fewer plants are eaten. Second-order predation combined with climate change exacerbates the effect of climate change.[249] (results graph at right).

The second-order predation hypothesis is supported by the observation above that there was a massive increase in bison populations.[258]

Arguments against the second-order predation hypothesis

- The multispecies model produces a mass extinction through indirect competition between herbivore species: small species with high reproductive rates subsidize predation on large species with low reproductive rates.[204] All prey species are lumped in the Pleistocene extinction model.

- The control of population sizes by predators is not fully supported by observations of modern ecosystems.[259]

Arguments against the second-order predation plus climate hypothesis

- It assumes decreases in vegetation due to climate change, but deglaciation doubled the habitable area of North America.

- Any vegetational changes that did occur failed to cause almost any extinctions of small vertebrates, and they are more narrowly distributed on average.

Younger Dryas impact hypothesis

The Younger Dryas impact hypothesis claims that a comet impact or air burst occurred in North America about 12,900 years ago as the mechanism that initiated the Younger Dryas cooling.[260] First publicly presented at the Spring 2007 joint assembly of the American Geophysical Union in Acapulco, Mexico, the Younger Dryas impact hypothesis has been discredited[261] and remains controversial.[262]

See also

- Earth:Holocene extinction – Ongoing extinction event caused by human activity

- Biology:List of quaternary mammalian fauna of China

- Biology:Megafauna – Large animals

- Biology:Pleistocene megafauna – Large animals that lived during the Pleistocene

- Biology:Pleistocene rewilding – Ecological practice

- Earth:Toba catastrophe theory – Supereruption 74,000 years ago that may have caused a global volcanic winter

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Stuart, Anthony John (1999), MacPhee, Ross D. E., ed., "Late Pleistocene Megafaunal Extinctions: A European Perspective" (in en), Extinctions in Near Time (Boston, MA: Springer US): pp. 257–269, doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-5202-1_11, ISBN 978-1-4419-3315-7, http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-1-4757-5202-1_11, retrieved 2023-05-28

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Sandom, Christopher; Faurby, Søren; Sandel, Brody; Svenning, Jens-Christian (2014-07-22). "Global late Quaternary megafauna extinctions linked to humans, not climate change" (in en). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 281 (1787): 20133254. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.3254. ISSN 0962-8452. PMID 24898370. PMC 4071532. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2013.3254.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Faith, J. Tyler; Surovell, Todd A. (2009-12-08). "Synchronous extinction of North America's Pleistocene mammals" (in en). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106 (49): 20641–20645. doi:10.1073/pnas.0908153106. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 19934040. PMC 2791611. https://pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.0908153106.

- ↑ Bird, Michael I.; Hutley, Lindsay B.; Lawes, Michael J.; Lloyd, Jon; Luly, Jon G.; Ridd, Peter V.; Roberts, Richard G.; Ulm, Sean et al. (July 2013). "Humans, megafauna and environmental change in tropical Australia: HUMANS, MEGAFAUNA AND ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE IN TROPICAL AUSTRALIA" (in en). Journal of Quaternary Science 28 (5): 439–452. doi:10.1002/jqs.2639. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jqs.2639.

- ↑ Dembitzer, Jacob; Barkai, Ran; Ben-Dor, Miki; Meiri, Shai (2022-01-15). "Levantine overkill: 1.5 million years of hunting down the body size distribution". Quaternary Science Reviews 276: 107316. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2021.107316. Bibcode: 2022QSRv..27607316D.

- ↑ Martin, Paul S.; Klein, Richard G. (1989). Quaternary Extinctions: A Prehistoric Revolution. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-1100-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=qIDC7ybvHQEC.

- ↑ Smith, Felisa A. (April 20, 2018). "Body size downgrading of mammals over the late Quaternary". Science 360 (6386): 310–313. doi:10.1126/science.aao5987. PMID 29674591. Bibcode: 2018Sci...360..310S.

- ↑ Koch, Paul L.; Barnosky, Anthony D. (2006-01-01). "Late Quaternary Extinctions: State of the Debate". Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 37 (1): 215–250. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132415.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Prado, José L.; Martinez-Maza, Cayetana; Alberdi, María T. (May 2015). "Megafauna extinction in South America: A new chronology for the Argentine Pampas" (in en). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 425: 41–49. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2015.02.026. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0031018215000899.

- ↑ Frédérik Saltré, Marta Rodríguez-Rey, Barry W. Brook, Christopher N Johnson (2016). "Climate change not to blame for late Quaternary megafauna extinctions in Australia". PubMed Central 7. doi:10.1038/ncomms10511. PMID 26821754. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4740174/.

- ↑ Putshkov, P. V. (1997). "Were the Mammoths killed by the warming? (Testing of the climatic versions of the Wurm extinctions)". Vestnik Zoologii (Supplement No.4).

- ↑ Rabanus-Wallace, M. Timothy; Wooller, Matthew J.; Zazula, Grant D.; Shute, Elen; Jahren, A. Hope; Kosintsev, Pavel; Burns, James A.; Breen, James et al. (2017). "Megafaunal isotopes reveal role of increased moisture on rangeland during late Pleistocene extinctions". Nature Ecology & Evolution 1 (5): 0125. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0125. PMID 28812683.