Kendall rank correlation coefficient

In statistics, the Kendall rank correlation coefficient, commonly referred to as Kendall's τ coefficient (after the Greek letter τ, tau), is a statistic used to measure the ordinal association between two measured quantities. A τ test is a non-parametric hypothesis test for statistical dependence based on the τ coefficient. It is a measure of rank correlation: the similarity of the orderings of the data when ranked by each of the quantities. It is named after Maurice Kendall, who developed it in 1938,[1] though Gustav Fechner had proposed a similar measure in the context of time series in 1897.[2]

Intuitively, the Kendall correlation between two variables will be high when observations have a similar or identical rank (i.e. relative position label of the observations within the variable: 1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc.) between the two variables, and low when observations have a dissimilar or fully reversed rank between the two variables.

Both Kendall's and Spearman's can be formulated as special cases of a more general correlation coefficient. Its notions of concordance and discordance also appear in other areas of statistics, like the Rand index in cluster analysis.

Definition

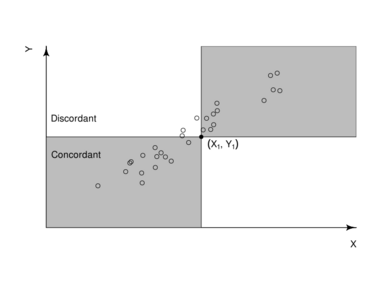

Let be a set of observations of the joint random variables X and Y, such that all the values of () and () are unique. (See the section Accounting for ties for ways of handling non-unique values.) Any pair of observations and , where , are said to be concordant if the sort order of and agrees: that is, if either both and holds or both and ; otherwise they are said to be discordant.

In the absence of ties, the Kendall τ coefficient is defined as:

for where is the binomial coefficient for the number of ways to choose two items from n items.

The number of discordant pairs is equal to the inversion number that permutes the y-sequence into the same order as the x-sequence.

Properties

The denominator is the total number of pair combinations, so the coefficient must be in the range −1 ≤ τ ≤ 1.

- If the agreement between the two rankings is perfect (i.e., the two rankings are the same) the coefficient has value 1.

- If the disagreement between the two rankings is perfect (i.e., one ranking is the reverse of the other) the coefficient has value −1.

- If X and Y are independent random variables and not constant, then the expectation of the coefficient is zero.

- An explicit expression for Kendall's rank coefficient is .

Hypothesis test

The Kendall rank coefficient is often used as a test statistic in a statistical hypothesis test to establish whether two variables may be regarded as statistically dependent. This test is non-parametric, as it does not rely on any assumptions on the distributions of X or Y or the distribution of (X,Y).

Under the null hypothesis of independence of X and Y, the sampling distribution of τ has an expected value of zero. The precise distribution cannot be characterized in terms of common distributions, but may be calculated exactly for small samples; for larger samples, it is common to use an approximation to the normal distribution, with mean zero and variance .[4]

Theorem. If the samples are independent, then the variance of is given by .

WLOG, we reorder the data pairs, so that . By assumption of independence, the order of is a permutation sampled uniformly at random from , the permutation group on .

For each permutation, its unique inversion code is such that each is in the range . Sampling a permutation uniformly is equivalent to sampling a -inversion code uniformly, which is equivalent to sampling each uniformly and independently.

Then we have

The first term is just . The second term can be calculated by noting that is a uniform random variable on , so and , then using the sum of squares formula again.

Asymptotic normality — At the limit, converges in distribution to the standard normal distribution.

Use a result from A class of statistics with asymptotically normal distribution Hoeffding (1948).[7]

Case of standard normal distributions

If are independent and identically distributed samples from the same jointly normal distribution with a known Pearson correlation coefficient , then the expectation of Kendall rank correlation has a closed-form formula.[8]

Greiner's equality — If are jointly normal, with correlation , then

The name is credited to Richard Greiner (1909)[9] by P. A. P. Moran.[10]

Define the following quantities.

- is a point in .

In the notation, we see that the number of concordant pairs, , is equal to the number of that fall in the subset . That is, .

Thus,

Since each is an independent and identically distributed sample of the jointly normal distribution, the pairing does not matter, so each term in the summation is exactly the same, and so and it remains to calculate the probability. We perform this by repeated affine transforms.

First normalize by subtracting the mean and dividing the standard deviation. This does not change . This gives us where is sampled from the standard normal distribution on .

Thus, where the vector is still distributed as the standard normal distribution on . It remains to perform some unenlightening tedious matrix exponentiations and trigonometry, which can be skipped over.

Thus, iff where the subset on the right is a “squashed” version of two quadrants. Since the standard normal distribution is rotationally symmetric, we need only calculate the angle spanned by each squashed quadrant.

The first quadrant is the sector bounded by the two rays . It is transformed to the sector bounded by the two rays and . They respectively make angle with the horizontal and vertical axis, where

Together, the two transformed quadrants span an angle of , so and therefore

Accounting for ties

A pair is said to be tied if and only if or ; a tied pair is neither concordant nor discordant. When tied pairs arise in the data, the coefficient may be modified in a number of ways to keep it in the range [−1, 1]:

Tau-a

The Tau statistic defined by Kendall in 1938[1] was retrospectively renamed Tau-a. It represents the strength of positive or negative association of two quantitative or ordinal variables without any adjustment for ties. It is defined as:

where nc, nd and n0 are defined as in the next section.

When ties are present, and, the coefficient can never be equal to +1 or −1. Even a perfect equality of the two variables (X=Y) leads to a Tau-a < 1.

Tau-b

The Tau-b statistic, unlike Tau-a, makes adjustments for ties. This Tau-b was first described by Kendall in 1945 under the name Tau-w[12] as an extension of the original Tau statistic supporting ties. Values of Tau-b range from −1 (100% negative association, or perfect disagreement) to +1 (100% positive association, or perfect agreement). In case of the absence of association, Tau-b is equal to zero.

The Kendall Tau-b coefficient is defined as :

where

A simple algorithm developed in BASIC computes Tau-b coefficient using an alternative formula.[13]

Be aware that some statistical packages, e.g. SPSS, use alternative formulas for computational efficiency, with double the 'usual' number of concordant and discordant pairs.[14]

Tau-c

Tau-c (also called Stuart-Kendall Tau-c)[15] was first defined by Stuart in 1953.[16] Contrary to Tau-b, Tau-c can be equal to +1 or −1 for non-square (i.e. rectangular) contingency tables,[15][16] i.e. when the underlying scales of both variables have different number of possible values. For instance, if the variable X has a continuous uniform distribution between 0 and 100 and Y is a dichotomous variable equal to 1 if X ≥ 50 and 0 if X < 50, the Tau-c statistic of X and Y is equal to 1 while Tau-b is equal to 0.707. A Tau-c equal to 1 can be interpreted as the best possible positive correlation conditional to marginal distributions while a Tau-b equal to 1 can be interpreted as the perfect positive monotonic correlation where the distribution of X conditional to Y has zero variance and the distribution of Y conditional to X has zero variance so that a bijective function f with f(X)=Y exists.

The Stuart-Kendall Tau-c coefficient is defined as:[16]

where

Significance tests

When two quantities are statistically dependent, the distribution of is not easily characterizable in terms of known distributions. However, for the following statistic, , is approximately distributed as a standard normal when the variables are statistically independent:

where .

Thus, to test whether two variables are statistically dependent, one computes , and finds the cumulative probability for a standard normal distribution at . For a 2-tailed test, multiply that number by two to obtain the p-value. If the p-value is below a given significance level, one rejects the null hypothesis (at that significance level) that the quantities are statistically independent.

Numerous adjustments should be added to when accounting for ties. The following statistic, , has the same distribution as the distribution, and is again approximately equal to a standard normal distribution when the quantities are statistically independent:

where

This is sometimes referred to as the Mann-Kendall test.[17]

Algorithms

The direct computation of the numerator , involves two nested iterations, as characterized by the following pseudocode:

numer := 0

for i := 2..N do

for j := 1..(i − 1) do

numer := numer + sign(x[i] − x[j]) × sign(y[i] − y[j])

return numer

Although quick to implement, this algorithm is in complexity and becomes very slow on large samples. A more sophisticated algorithm[18] built upon the Merge Sort algorithm can be used to compute the numerator in time.

Begin by ordering your data points sorting by the first quantity, , and secondarily (among ties in ) by the second quantity, . With this initial ordering, is not sorted, and the core of the algorithm consists of computing how many steps a Bubble Sort would take to sort this initial . An enhanced Merge Sort algorithm, with complexity, can be applied to compute the number of swaps, , that would be required by a Bubble Sort to sort . Then the numerator for is computed as:

where is computed like and , but with respect to the joint ties in and .

A Merge Sort partitions the data to be sorted, into two roughly equal halves, and , then sorts each half recursively, and then merges the two sorted halves into a fully sorted vector. The number of Bubble Sort swaps is equal to:

where and are the sorted versions of and , and characterizes the Bubble Sort swap-equivalent for a merge operation. is computed as depicted in the following pseudo-code:

function M(L[1..n], R[1..m]) is

i := 1

j := 1

nSwaps := 0

while i ≤ n and j ≤ m do

if R[j] < L[i] then

nSwaps := nSwaps + n − i + 1

j := j + 1

else

i := i + 1

return nSwaps

A side effect of the above steps is that you end up with both a sorted version of and a sorted version of . With these, the factors and used to compute are easily obtained in a single linear-time pass through the sorted arrays.

Approximating Kendall rank correlation from a stream

Efficient algorithms for calculating the Kendall rank correlation coefficient as per the standard estimator have time complexity. However, these algorithms necessitate the availability of all data to determine observation ranks, posing a challenge in sequential data settings where observations are revealed incrementally. Fortunately, algorithms do exist to estimate the Kendall rank correlation coefficient in sequential settings.[19][20] These algorithms have update time and space complexity, scaling efficiently with the number of observations. Consequently, when processing a batch of observations, the time complexity becomes , while space complexity remains a constant .

The first such algorithm[19] presents an approximation to the Kendall rank correlation coefficient based on coarsening the joint distribution of the random variables. Non-stationary data is treated via a moving window approach. This algorithm[19] is simple and is able to handle discrete random variables along with continuous random variables without modification.

The second algorithm[20] is based on Hermite series estimators and utilizes an alternative estimator for the exact Kendall rank correlation coefficient i.e. for the probability of concordance minus the probability of discordance of pairs of bivariate observations. This alternative estimator also serves as an approximation to the standard estimator. This algorithm[20] is only applicable to continuous random variables, but it has demonstrated superior accuracy and potential speed gains compared to the first algorithm described,[19] along with the capability to handle non-stationary data without relying on sliding windows. An efficient implementation of the Hermite series based approach is contained in the R package package hermiter.[20]

Software implementations

- R implements the test for

cor.test(x, y, method = "kendall")in its "stats" package (alsocor(x, y, method = "kendall")will work, but the latter does not return the p-value). All three versions of the coefficient are available in the "DescTools" package along with the confidence intervals:KendallTauA(x,y,conf.level=0.95)for ,KendallTauB(x,y,conf.level=0.95)for ,StuartTauC(x,y,conf.level=0.95)for . Fast batch estimates of the Kendall rank correlation coefficient along with sequential estimates are provided for in the package hermiter.[20] - For Python, the SciPy library implements the computation of in

scipy.stats.kendalltau - In Stata is implemented as

ktau varlist.

See also

- Correlation

- Kendall tau distance

- Kendall's W

- Spearman's rank correlation coefficient

- Goodman and Kruskal's gamma

- Theil–Sen estimator

- Mann–Whitney U test - it is equivalent to Kendall's tau correlation coefficient if one of the variables is binary.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Kendall, M. G. (1938). "A New Measure of Rank Correlation". Biometrika 30 (1–2): 81–89. doi:10.1093/biomet/30.1-2.81.

- ↑ "Ordinal Measures of Association". Journal of the American Statistical Association 53 (284): 814–861. 1958. doi:10.2307/2281954.

- ↑ Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Kendall tau metric", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=K/k130020

- ↑ Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Kendall coefficient of rank correlation", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=K/k055200

- ↑ Valz, Paul D.; McLeod, A. Ian (February 1990). "A Simplified Derivation of the Variance of Kendall's Rank Correlation Coefficient" (in en). The American Statistician 44 (1): 39–40. doi:10.1080/00031305.1990.10475691. ISSN 0003-1305. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00031305.1990.10475691.

- ↑ Valz, Paul D.; McLeod, A. Ian; Thompson, Mary E. (February 1995). "Cumulant Generating Function and Tail Probability Approximations for Kendall's Score with Tied Rankings". The Annals of Statistics 23 (1): 144–160. doi:10.1214/aos/1176324460. ISSN 0090-5364.

- ↑ Hoeffding, Wassily (1992), Kotz, Samuel; Johnson, Norman L., eds., "A Class of Statistics with Asymptotically Normal Distribution" (in en), Breakthroughs in Statistics: Foundations and Basic Theory, Springer Series in Statistics (New York, NY: Springer): pp. 308–334, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-0919-5_20, ISBN 978-1-4612-0919-5, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-0919-5_20, retrieved 2024-01-19

- ↑ Kendall, M. G. (1949). "Rank and Product-Moment Correlation". Biometrika 36 (1/2): 177–193. doi:10.2307/2332540. ISSN 0006-3444. PMID 18132091. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2332540.

- ↑ Richard Greiner, (1909), Ueber das Fehlersystem der Kollektiv-maßlehre, Zeitschrift für Mathematik und Physik, Band 57, B. G. Teubner, Leipzig, pages 121-158, 225-260, 337-373.

- ↑ Moran, P. A. P. (1948). "Rank Correlation and Product-Moment Correlation". Biometrika 35 (1/2): 203–206. doi:10.2307/2332641. ISSN 0006-3444. PMID 18867425. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2332641.

- ↑ Berger, Daniel (2016). "A Proof of Greiner's Equality" (in en). SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2830471. ISSN 1556-5068. https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=2830471.

- ↑ Kendall, M. G. (1945). "The Treatment of Ties in Ranking Problems". Biometrika 33 (3): 239–251. doi:10.2307/2332303. PMID 21006841. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2332303. Retrieved 12 November 2024.

- ↑ Alfred Brophy (1986). "An algorithm and program for calculation of Kendall's rank correlation coefficient". Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers 18: 45–46. doi:10.3758/BF03200993. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.3758/BF03200993.pdf.

- ↑ IBM (2016). IBM SPSS Statistics 24 Algorithms. IBM. p. 168. http://www-01.ibm.com/support/docview.wss?uid=swg27047033#en. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Berry, K. J.; Johnston, J. E.; Zahran, S.; Mielke, P. W. (2009). "Stuart's tau measure of effect size for ordinal variables: Some methodological considerations". Behavior Research Methods 41 (4): 1144–1148. doi:10.3758/brm.41.4.1144. PMID 19897822.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Stuart, A. (1953). "The Estimation and Comparison of Strengths of Association in Contingency Tables". Biometrika 40 (1–2): 105–110. doi:10.2307/2333101.

- ↑ Valz, Paul D.; McLeod, A. Ian; Thompson, Mary E. (February 1995). "Cumulant Generating Function and Tail Probability Approximations for Kendall's Score with Tied Rankings". The Annals of Statistics 23 (1): 144–160. doi:10.1214/aos/1176324460. ISSN 0090-5364.

- ↑ Knight, W. (1966). "A Computer Method for Calculating Kendall's Tau with Ungrouped Data". Journal of the American Statistical Association 61 (314): 436–439. doi:10.2307/2282833.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Xiao, W. (2019). "Novel Online Algorithms for Nonparametric Correlations with Application to Analyze Sensor Data". 2019 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data). pp. 404–412. doi:10.1109/BigData47090.2019.9006483. ISBN 978-1-7281-0858-2.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 Stephanou, M. and Varughese, M (2023). "Hermiter: R package for sequential nonparametric estimation". Computational Statistics. doi:10.1007/s00180-023-01382-0.

Further reading

- Abdi, H. (2007). "Kendall rank correlation". in Salkind, N.J.. Encyclopedia of Measurement and Statistics. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage. http://www.utdallas.edu/~herve/Abdi-KendallCorrelation2007-pretty.pdf.

- Daniel, Wayne W. (1990). "Kendall's tau". Applied Nonparametric Statistics (2nd ed.). Boston: PWS-Kent. pp. 365–377. ISBN 978-0-534-91976-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=0hPvAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA365.

- Kendall, Maurice; Gibbons, Jean Dickinson (1990). Rank Correlation Methods. Charles Griffin Book Series (5th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195208375. https://archive.org/details/rankcorrelationm0000kend.

- Bonett, Douglas G.; Wright, Thomas A. (2000). "Sample size requirements for estimating Pearson, Kendall, and Spearman correlations". Psychometrika 65 (1): 23–28. doi:10.1007/BF02294183.

External links

- Tied rank calculation

- Software for computing Kendall's tau on very large datasets

- Online software: computes Kendall's tau rank correlation

de:Rangkorrelationskoeffizient#Kendalls Tau

|