Gauss–Newton algorithm

Top: Raw data and model.

Bottom: Evolution of the normalised sum of the squares of the errors.

The Gauss–Newton algorithm is used to solve non-linear least squares problems, which is equivalent to minimizing a sum of squared function values. It is an extension of Newton's method for finding a minimum of a non-linear function. Since a sum of squares must be nonnegative, the algorithm can be viewed as using Newton's method to iteratively approximate zeroes of the components of the sum, and thus minimizing the sum. In this sense, the algorithm is also an effective method for solving overdetermined systems of equations. It has the advantage that second derivatives, which can be challenging to compute, are not required.[1]

Non-linear least squares problems arise, for instance, in non-linear regression, where parameters in a model are sought such that the model is in good agreement with available observations.

The method is named after the mathematicians Carl Friedrich Gauss and Isaac Newton, and first appeared in Gauss's 1809 work Theoria motus corporum coelestium in sectionibus conicis solem ambientum.[2]

Description

Given functions (often called residuals) of variables with the Gauss–Newton algorithm iteratively finds the value of that minimize the sum of squares[3]

Starting with an initial guess for the minimum, the method proceeds by the iterations

where, if r and β are column vectors, the entries of the Jacobian matrix are

and the symbol denotes the matrix transpose.

At each iteration, the update can be found by rearranging the previous equation in the following two steps:

With substitutions , , and , this turns into the conventional matrix equation of form , which can then be solved in a variety of methods (see Notes).

If m = n, the iteration simplifies to

which is a direct generalization of Newton's method in one dimension.

In data fitting, where the goal is to find the parameters such that a given model function best fits some data points , the functions are the residuals:

Then, the Gauss–Newton method can be expressed in terms of the Jacobian of the function as

Note that is the left pseudoinverse of .

Notes

The assumption m ≥ n in the algorithm statement is necessary, as otherwise the matrix is not invertible and the normal equations cannot be solved (at least uniquely).

The Gauss–Newton algorithm can be derived by linearly approximating the vector of functions ri. Using Taylor's theorem, we can write at every iteration:

with . The task of finding minimizing the sum of squares of the right-hand side; i.e.,

is a linear least-squares problem, which can be solved explicitly, yielding the normal equations in the algorithm.

The normal equations are n simultaneous linear equations in the unknown increments . They may be solved in one step, using Cholesky decomposition, or, better, the QR factorization of . For large systems, an iterative method, such as the conjugate gradient method, may be more efficient. If there is a linear dependence between columns of Jr, the iterations will fail, as becomes singular.

When is complex the conjugate form should be used: .

Example

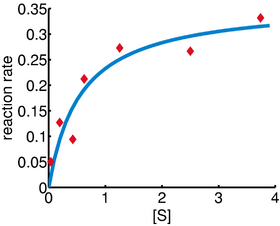

In this example, the Gauss–Newton algorithm will be used to fit a model to some data by minimizing the sum of squares of errors between the data and model's predictions.

In a biology experiment studying the relation between substrate concentration [S] and reaction rate in an enzyme-mediated reaction, the data in the following table were obtained.

| i | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [S] | 0.038 | 0.194 | 0.425 | 0.626 | 1.253 | 2.500 | 3.740 |

| Rate | 0.050 | 0.127 | 0.094 | 0.2122 | 0.2729 | 0.2665 | 0.3317 |

It is desired to find a curve (model function) of the form

that fits best the data in the least-squares sense, with the parameters and to be determined.

Denote by and the values of [S] and rate respectively, with . Let and . We will find and such that the sum of squares of the residuals

is minimized.

The Jacobian of the vector of residuals with respect to the unknowns is a matrix with the -th row having the entries

Starting with the initial estimates of and , after five iterations of the Gauss–Newton algorithm, the optimal values and are obtained. The sum of squares of residuals decreased from the initial value of 1.445 to 0.00784 after the fifth iteration. The plot in the figure on the right shows the curve determined by the model for the optimal parameters with the observed data.

Convergence properties

The Gauss-Newton iteration is guaranteed to converge toward a local minimum point under 4 conditions:[4] The functions are twice continuously differentiable in an open convex set , the Jacobian is of full column rank, the initial iterate is near , and the local minimum value is small. The convergence is quadratic if .

It can be shown[5] that the increment Δ is a descent direction for S, and, if the algorithm converges, then the limit is a stationary point of S. For large minimum value , however, convergence is not guaranteed, not even local convergence as in Newton's method, or convergence under the usual Wolfe conditions.[6]

The rate of convergence of the Gauss–Newton algorithm can approach quadratic.[7] The algorithm may converge slowly or not at all if the initial guess is far from the minimum or the matrix is ill-conditioned. For example, consider the problem with equations and variable, given by

For , is a local optimum. If , then the problem is in fact linear and the method finds the optimum in one iteration. If |λ| < 1, then the method converges linearly and the error decreases asymptotically with a factor |λ| at every iteration. However, if |λ| > 1, then the method does not even converge locally.[8]

Solving overdetermined systems of equations

The Gauss-Newton iteration is an effective method for solving overdetermined systems of equations in the form of with and where is the Moore-Penrose inverse (also known as pseudoinverse) of the Jacobian matrix of . It can be considered an extension of Newton's method and enjoys the same local quadratic convergence [4] toward isolated regular solutions.

If the solution doesn't exist but the initial iterate is near a point at which the sum of squares reaches a small local minimum, the Gauss-Newton iteration linearly converges to . The point is often called a least squares solution of the overdetermined system.

Derivation from Newton's method

In what follows, the Gauss–Newton algorithm will be derived from Newton's method for function optimization via an approximation. As a consequence, the rate of convergence of the Gauss–Newton algorithm can be quadratic under certain regularity conditions. In general (under weaker conditions), the convergence rate is linear.[9]

The recurrence relation for Newton's method for minimizing a function S of parameters is

where g denotes the gradient vector of S, and H denotes the Hessian matrix of S.

Since , the gradient is given by

Elements of the Hessian are calculated by differentiating the gradient elements, , with respect to :

The Gauss–Newton method is obtained by ignoring the second-order derivative terms (the second term in this expression). That is, the Hessian is approximated by

where are entries of the Jacobian Jr. Note that when the exact hessian is evaluated near an exact fit we have near-zero , so the second term becomes near-zero as well, which justifies the approximation. The gradient and the approximate Hessian can be written in matrix notation as

These expressions are substituted into the recurrence relation above to obtain the operational equations

Convergence of the Gauss–Newton method is not guaranteed in all instances. The approximation

that needs to hold to be able to ignore the second-order derivative terms may be valid in two cases, for which convergence is to be expected:[10]

- The function values are small in magnitude, at least around the minimum.

- The functions are only "mildly" nonlinear, so that is relatively small in magnitude.

Improved versions

With the Gauss–Newton method the sum of squares of the residuals S may not decrease at every iteration. However, since Δ is a descent direction, unless is a stationary point, it holds that for all sufficiently small . Thus, if divergence occurs, one solution is to employ a fraction of the increment vector Δ in the updating formula:

In other words, the increment vector is too long, but it still points "downhill", so going just a part of the way will decrease the objective function S. An optimal value for can be found by using a line search algorithm, that is, the magnitude of is determined by finding the value that minimizes S, usually using a direct search method in the interval or a backtracking line search such as Armijo-line search. Typically, should be chosen such that it satisfies the Wolfe conditions or the Goldstein conditions.[11]

In cases where the direction of the shift vector is such that the optimal fraction α is close to zero, an alternative method for handling divergence is the use of the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm, a trust region method.[3] The normal equations are modified in such a way that the increment vector is rotated towards the direction of steepest descent,

where D is a positive diagonal matrix. Note that when D is the identity matrix I and , then , therefore the direction of Δ approaches the direction of the negative gradient .

The so-called Marquardt parameter may also be optimized by a line search, but this is inefficient, as the shift vector must be recalculated every time is changed. A more efficient strategy is this: When divergence occurs, increase the Marquardt parameter until there is a decrease in S. Then retain the value from one iteration to the next, but decrease it if possible until a cut-off value is reached, when the Marquardt parameter can be set to zero; the minimization of S then becomes a standard Gauss–Newton minimization.

Large-scale optimization

For large-scale optimization, the Gauss–Newton method is of special interest because it is often (though certainly not always) true that the matrix is more sparse than the approximate Hessian . In such cases, the step calculation itself will typically need to be done with an approximate iterative method appropriate for large and sparse problems, such as the conjugate gradient method.

In order to make this kind of approach work, one needs at least an efficient method for computing the product

for some vector p. With sparse matrix storage, it is in general practical to store the rows of in a compressed form (e.g., without zero entries), making a direct computation of the above product tricky due to the transposition. However, if one defines ci as row i of the matrix , the following simple relation holds:

so that every row contributes additively and independently to the product. In addition to respecting a practical sparse storage structure, this expression is well suited for parallel computations. Note that every row ci is the gradient of the corresponding residual ri; with this in mind, the formula above emphasizes the fact that residuals contribute to the problem independently of each other.

Related algorithms

In a quasi-Newton method, such as that due to Davidon, Fletcher and Powell or Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno (BFGS method) an estimate of the full Hessian is built up numerically using first derivatives only so that after n refinement cycles the method closely approximates to Newton's method in performance. Note that quasi-Newton methods can minimize general real-valued functions, whereas Gauss–Newton, Levenberg–Marquardt, etc. fits only to nonlinear least-squares problems.

Another method for solving minimization problems using only first derivatives is gradient descent. However, this method does not take into account the second derivatives even approximately. Consequently, it is highly inefficient for many functions, especially if the parameters have strong interactions.

Example implementations

Julia

The following implementation in Julia provides one method which uses a provided Jacobian and another computing with automatic differentiation.

"""

gaussnewton(r, J, β₀, maxiter, tol)

Perform Gauss–Newton optimization to minimize the residual function `r` with Jacobian `J` starting from `β₀`. The algorithm terminates when the norm of the step is less than `tol` or after `maxiter` iterations.

"""

function gaussnewton(r, J, β₀, maxiter, tol)

β = copy(β₀)

for _ in 1:maxiter

Jβ = J(β);

Δ = -(Jβ' * Jβ) \ (Jβ' * r(β))

β += Δ

if sqrt(sum(abs2, Δ)) < tol

break

end

end

return β

end

import AbstractDifferentiation as AD, Zygote

backend = AD.ZygoteBackend() # other backends are available

"""

gaussnewton(r, β₀, maxiter, tol)

Perform Gauss–Newton optimization to minimize the residual function `r` starting from `β₀`. The relevant Jacobian is calculated using automatic differentiation. The algorithm terminates when the norm of the step is less than `tol` or after `maxiter` iterations.

"""

function gaussnewton(r, β₀, maxiter, tol)

β = copy(β₀)

for _ in 1:maxiter

rβ, Jβ = AD.value_and_jacobian(backend, r, β)

Δ = -(Jβ[1]' * Jβ[1]) \ (Jβ[1]' * rβ)

β += Δ

if sqrt(sum(abs2, Δ)) < tol

break

end

end

return β

end

Notes

- ↑ Mittelhammer, Ron C.; Miller, Douglas J.; Judge, George G. (2000). Econometric Foundations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 197–198. ISBN 0-521-62394-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=fycmsfkK6RQC&pg=PA197.

- ↑ Floudas, Christodoulos A.; Pardalos, Panos M. (2008). Encyclopedia of Optimization. Springer. p. 1130. ISBN 9780387747583.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Björck (1996)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 J.E. Dennis, Jr. and R.B. Schnabel (1983). Numerical Methods for Unconstrained Optimization and Nonlinear Equations. SIAM 1996 reproduction of Prentice-Hall 1983 edition. p. 222.

- ↑ Björck (1996), p. 260.

- ↑ Mascarenhas (2013), "The divergence of the BFGS and Gauss Newton Methods", Mathematical Programming 147 (1): 253–276, doi:10.1007/s10107-013-0720-6

- ↑ Björck (1996), p. 341, 342.

- ↑ Fletcher (1987), p. 113.

- ↑ "Archived copy". http://www.henley.ac.uk/web/FILES/maths/09-04.pdf.

- ↑ Nocedal (1999), p. 259.

- ↑ Nocedal, Jorge. (1999). Numerical optimization. Wright, Stephen J., 1960-. New York: Springer. ISBN 0387227423. OCLC 54849297.

References

- Björck, A. (1996). Numerical methods for least squares problems. SIAM, Philadelphia. ISBN 0-89871-360-9.

- Fletcher, Roger (1987). Practical methods of optimization (2nd ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-91547-8. https://archive.org/details/practicalmethods0000flet..

- Nocedal, Jorge; Wright, Stephen (1999). Numerical optimization. New York: Springer. ISBN 0-387-98793-2.

External links

- Probability, Statistics and Estimation The algorithm is detailed and applied to the biology experiment discussed as an example in this article (page 84 with the uncertainties on the estimated values).

Implementations

- Artelys Knitro is a non-linear solver with an implementation of the Gauss–Newton method. It is written in C and has interfaces to C++/C#/Java/Python/MATLAB/R.

|