Physics:Dual photon

| Composition | Elementary particle |

|---|---|

| Statistics | Bosonic |

| Interactions | Electromagnetic |

| Status | Hypothetical |

| Theorized | 2000s[1][2][3][4][5] |

| electric charge | 0 e |

| Spin | 1 ħ |

| String theory |

|---|

|

| Fundamental objects |

| Perturbative theory |

| Non-perturbative results |

| Phenomenology |

| Mathematics |

| Beyond the Standard Model |

|---|

|

| Standard Model |

In theoretical physics, the dual photon is a hypothetical elementary particle that is a dual of the photon under electric–magnetic duality which is predicted by some theoretical models,[3][4][5] including M-theory.[1][2]

It has been shown that including magnetic monopole in Maxwell's equations introduces a singularity. The only way to avoid the singularity is to include a second four-vector potential, called dual photon, in addition to the usual four-vector potential, photon.[6] Additionally, it is found that the standard Lagrangian of electromagnetism is not symmetric under duality (i.e. symmetric under rotation between electric and magnetic charges), which causes problems for the stress–energy, spin, and orbital angular momentum tensors. To resolve this issue, a dual symmetric Lagrangian of electromagnetism has been proposed,[3] which has a self-consistent separation of the spin and orbital degrees of freedom. The Poincaré symmetries imply that the dual electromagnetism naturally makes self-consistent conservation laws.[3]

Dual electromagnetism

The free electromagnetic field is described by a covariant antisymmetric tensor of rank 2 by

where is the electromagnetic potential.

The dual electromagnetic field is defined as

where is the Hodge star, and is the Levi-Civita tensor

For the electromagnetic field and its dual field, we have

Then, for a given gauge field , the dual configuration is defined as[2]

where the field potential of the dual photon, and non-locally linked to the original field potential .

p-form electrodynamics

A p-form generalization of Maxwell's theory of electromagnetism is described by a gauge-invariant 2-form defined as

- .

which satisfies the equation of motion

where is the Hodge star.

This implies the following action in the spacetime manifold :[7][8]

where is the Hodge dual of the gauge-invariant 2-form for the electromagnetic field.

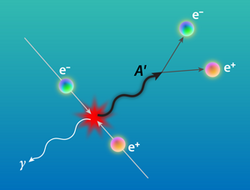

Dark photon

The dark photon is a spin-1 boson associated with a U(1) gauge field, which could be massless[10] and behaves like electromagnetism. But, it could be unstable and massive, quickly decays into electron–positron pairs, and interact with electrons.

The dark photon was first suggested in 2008 by Lotty Ackerman, Matthew R. Buckley, Sean M. Carroll, and Marc Kamionkowski to explain the 'g–2 anomaly' in experiment E821 at Brookhaven National Laboratory.[11] Nevertheless, it was ruled out in some experiments such as the PHENIX detector at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider at Brookhaven.[12]

In 2015, the Hungarian Academy of Sciences's Institute for Nuclear Research in Debrecen, Hungary, suggested the existence of a new, light spin-1 boson, dubbed the X17 particle, 34 times heavier than the electron[13] that decays into a pair of electron and positron with a combined energy of 17 MeV. In 2016, it was proposed that it is an X-boson with a mass of 16.7 MeV/c2, which explains the g−2 muon anomaly.[13][14]

See also

- Physics:'t Hooft loop – Magnetic loop operator dual to the Wilson loop

- Covariant Maxwell's equations – Ways of writing certain laws of physics

- Astronomy:Dark radiation – Postulated type of radiation that mediates interactions of dark matter

- Physics:Dual graviton

- Electromagnetic mathematics – Formulations of electromagnetism

- Physics:Kalb–Ramond field – Two-form field

- Physics:P-form electrodynamics – Generalization of electrodynamics

- Physics:Photino

- Physics:Photon

- Magnetic monopole

- Physics:Magnetic photon – Hypothetical particle

- Maxwell's equations – Electromagnetism in general relativity

- Physics:List of hypothetical particles

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Tong, D.; Lambert, N. (2008). "Membranes on an Orbifold". Physical Review Letters 101 (4). doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.041602. PMID 18764318. Bibcode: 2008PhRvL.101d1602L.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Bakas, I. (2010). "Dual photons and gravitons". Publ.Astron.Obs.Belgrade 88: 113–132. Bibcode: 2010POBeo..88..113B.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Bliokh, K. Y.; Bekshaev, A. Y.; Nori, F. (2013). "Dual electromagnetism: helicity, spin, momentum and angular momentum". New Journal of Physics 15 (3). doi:10.1088/1367-2630/15/3/033026. Bibcode: 2013NJPh...15c3026B.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Elbistan, M.; Duval, C.; Horváthy, P. A.; Zhang, P.-M. (2016). "Duality and helicity: A symplectic viewpoint". Physics Letters B 761: 265–268. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2016.08.041. Bibcode: 2016PhLB..761..265E.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Elbistan, M.; Horváthy, P. A.; Zhang, P.-M. (2017). "Duality and helicity: the photon wave function approach". Physics Letters A 381 (30): 2375–2379. doi:10.1016/j.physleta.2017.05.042. Bibcode: 2017PhLA..381.2375E.

- ↑ Singleton, D. (1996). "Electromagnetism with magnetic charge and two photons". American Journal of Physics 64 (4): 452–458. doi:10.1119/1.18191. Bibcode: 1996AmJPh..64..452S.

- ↑ Henneaux, M.; Teitelboim, C. (1986). "p-Form electrodynamics". Foundations of Physics 16 (7): 593–617. doi:10.1007/BF01889624. Bibcode: 1986FoPh...16..593H.

- ↑ Henneaux, M.; Bunster, C. (2011). "Action for twisted self-duality". Physical Review D 83 (12). doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.83.125015. Bibcode: 2011PhRvD..83l5015B.

- ↑ "Viewpoint: New Light Shed on Dark Photons" (Press release). American Physical Society. 10 November 2014.

- ↑ Carroll, Sean M. (October 29, 2008). "Dark photons". http://www.preposterousuniverse.com/blog/2008/10/29/dark-photons/.

- ↑ Bennett, G. W.; Bousquet, B.; Brown, H. N.; Bunce, G.; Carey, R. M.; Cushman, P.; Danby, G. T.; Debevec, P. T. (2006-04-07). "Final report of the E821 muon anomalous magnetic moment measurement at BNL". Physical Review D 73 (7). doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.73.072003. Bibcode: 2006PhRvD..73g2003B.

- ↑ Walsh, Karen McNulty (February 19, 2015). "Data from RHIC, other experiments nearly rule out role of 'dark photons' as explanation for 'g-2' anomaly". PhysOrg. http://phys.org/news/2015-02-rhic-role-dark-photons-explanation.html.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Cartlidge, Edwin (2016). "Has a Hungarian physics lab found a fifth force of nature?". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.19957. http://www.nature.com/news/has-a-hungarian-physics-lab-found-a-fifth-force-of-nature-1.19957.

- ↑ Feng, J. L.; Fornal, B.; Galon, I.; Gardner, S.; Smolinsky, J.; Tait, T. M. P.; Tanedo, P. (2016). "Protophobic Fifth-Force Interpretation of the Observed Anomaly in 8Be Nuclear Transitions". Physical Review Letters 117 (7). doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.117.071803. PMID 27563952. Bibcode: 2016PhRvL.117g1803F. https://zenodo.org/record/1059042.

|