Chemistry:Substance P

| tachykinin, precursor 1 | |

|---|---|

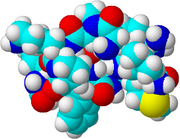

Spacefilling model of substance P | |

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | TAC1 |

| Alt. symbols | TAC2, NKNA |

| NCBI gene | 6863 |

| HGNC | 11517 |

| OMIM | 162320 |

| RefSeq | NM_003182 |

| UniProt | P20366 |

| Other data | |

| Locus | Chr. 7 q21-q22 |

| |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| MeSH | Substance+P |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| Properties | |

| C63H98N18O13S | |

| Molar mass | 1347.63 g/mol |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

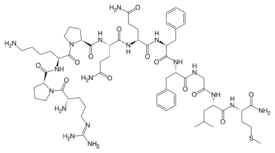

Substance P (SP) is an undecapeptide (a peptide composed of a chain of 11 amino acid residues)[1] and a type of neuropeptide, belonging to the tachykinin family of neuropeptides. It acts as a neurotransmitter and a neuromodulator.[2][3] Substance P and the closely related neurokinin A (NKA) are produced from a polyprotein precursor after alternative splicing of the preprotachykinin A gene. The deduced amino acid sequence of substance P is as follows:[4]

with an amide group at the C-terminus.[5] Substance P is released from the terminals of specific sensory nerves. It is found in the brain and spinal cord and is associated with inflammatory processes and pain.

Discovery

The original discovery of Substance P (SP) was in 1931 by Ulf von Euler and John H. Gaddum as a tissue extract that caused intestinal contraction in vitro.[6] Its tissue distribution and biologic actions were further investigated over the following decades.[2] The eleven-amino-acid structure of the peptide was determined by Chang, et. al in 1971.[7]

In 1983, Neurokinin A (previously known as substance K or neuromedin L) was isolated from porcine spinal cord and was also found to stimulate intestinal contraction.[8]

Receptor

The endogenous receptor for substance P is neurokinin 1 receptor (NK1-receptor, NK1R).[9] It belongs to the tachykinin receptor sub-family of GPCRs.[10] Other neurokinin subtypes and neurokinin receptors that interact with SP have been reported as well. Amino acid residues that are responsible for the binding of SP and its antagonists are present in the extracellular loops and transmembrane regions of NK-1. Binding of SP to NK-1R results in internalization by the clathrin-dependent mechanism to the acidified endosomes where the complex disassociates. Subsequently, SP is degraded and NK-1R is re-expressed on the cell surface.[11]

Substance P and the NK1-receptor are widely distributed in the brain and are found in brain regions that are specific to regulating emotion (hypothalamus, amygdala, and the periaqueductal gray).[12] They are found in close association with serotonin (5-HT) and neurons containing norepinephrine that are targeted by the currently used antidepressant drugs.[13] The SP receptor promoter contains regions that are sensitive to cAMP, AP-1, AP-4, CEBPB,[14] and epidermal growth factor. Because these regions are related to complexed signal transduction pathways mediated by cytokines, it has been proposed that cytokines and neurotropic factors can induce NK-1. Also, SP can induce the cytokines that are capable of inducing NK-1 transcription factors.[15]

Function

Overview

Substance P ("P" standing for "Preparation" or "Powder") is a neuropeptide – but only nominally so, as it is ubiquitous. Its receptor – the neurokinin type 1 – is distributed over cytoplasmic membranes of many cell types (neurons, glia, endothelia of capillaries and lymphatics, fibroblasts, stem cells, white blood cells) in many tissues and organs. SP amplifies or excites most cellular processes.[16][17]

Substance P is a key first responder to most noxious/extreme stimuli (stressors), i.e., those with a potential to compromise biological integrity.[clarification needed] SP is thus regarded as an immediate defense, stress, repair, survival system. The molecule, which is rapidly inactivated (or at times further activated by peptidases) is rapidly released – repetitively and chronically, as warranted, in the presence of a stressor. Unique among biological processes, SP release (and expression of its NK1 Receptor (through autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine-like processes)) may not naturally subside in diseases marked by chronic inflammation (including cancer). The SP or its NK1R, as well as similar neuropeptides, appear to be vital targets capable of satisfying many unmet medical needs. The failure of clinical proof of concept studies, designed to confirm various preclinical predictions of efficacy, is currently a source of frustration and confusion among biomedical researchers.

Vasodilation

Substance P is a potent vasodilator. Substance P-induced vasodilation is dependent on nitric oxide release.[18] Substance P is involved in the axon reflex-mediated vasodilation to local heating and wheal and flare reaction. It has been shown that vasodilation to substance P is dependent on the NK1 receptor located on the endothelium. In contrast to other neuropeptides studied in human skin, substance P-induced vasodilation has been found to decline during continuous infusion. This possibly suggests an internalization of neurokinin-1 (NK1).[19] As is typical with many vasodilators, it also has bronchoconstrictive properties, administered through the non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic nervous system (branch of the vagal system).

Inflammation

SP initiates expression of almost all known immunological chemical messengers (cytokines).[20][21][22] Also, most of the cytokines, in turn, induce SP and the NK1 receptor.[23][24] SP is particularly excitatory to cell growth and multiplication,[25] via usual,[26] as well as oncogenic drivers. [27] SP is a trigger for nausea and emesis.[28] Substance P and other sensory neuropeptides can be released from the peripheral terminals of sensory nerve fibers in the skin, muscle, and joints. It is proposed that this release is involved in neurogenic inflammation, which is a local inflammatory response to certain types of infection or injury.[29]

Pain

Preclinical data support the notion that Substance P is an important element in pain perception. The sensory function of substance P is thought to be related to the transmission of pain information into the central nervous system. Substance P coexists with the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate in primary afferents that respond to painful stimulation.[30] Substance P and other sensory neuropeptides can be released from the peripheral terminals of sensory nerve fibers in the skin, muscle, and joints. It is proposed that this release is involved in neurogenic inflammation, which is a local inflammatory response to certain types of infection or injury.[29] Unfortunately, the reasons why NK1 receptor antagonists have failed as efficacious analgesics in well-conducted clinical proof of concept studies have not yet been persuasively elucidated.

Mood, anxiety, learning

Substance P has been associated with the regulation of mood disorders, anxiety, stress,[31] reinforcement,[32] neurogenesis,[33] synaptic growth and dendritic arborisation,[34] respiratory rhythm,[35] neurotoxicity, pain, and nociception.[36] In 2014, it was found that substance P played a role in male fruit fly aggression.[37] Recently, it has been shown that substance P may play a critical role in long-term potentiation of aversive stimuli. [38]

Vomiting

The vomiting center in the medulla, called the area postrema, contains high concentrations of substance P and its receptor, in addition to other neurotransmitters such as choline, histamine, dopamine, serotonin, and endogenous opioids. Their activation stimulates the vomiting reflex. Different emetic pathways exist, and substance P/NK1R appears to be within the final common pathway to regulate vomiting.[39]

Cell growth, proliferation, angiogenesis, and migration

The above processes are part and parcel to tissue integrity and repair. Substance P has been known to stimulate cell growth in normal and cancer cell line cultures,[40] and it was shown that substance P could promote wound healing of non-healing ulcers in humans.[41] SP and its induced cytokines promote multiplication of cells required for repair or replacement, growth of new blood vessels,[42] and "leg-like pods" on cells (including cancer cells) bestowing upon them mobility,[43] and metastasis.[44] It has been suggested that cancer exploits the SP-NK1R to progress and metastasize, and that NK1RAs may be useful in the treatment of several cancer types.[45][46][47][48]

Clinical significance

Quantification in disease

Elevation of serum, plasma, or tissue SP and/or its receptor (NK1R) has been associated with many diseases: sickle cell crisis;[49] inflammatory bowel disease;[50][51] major depression and related disorders;[52][53][54] fibromyalgia;[55] rheumatological;[56] and infections such as HIV/AIDS and respiratory syncytial virus,[57] as well as in cancer.[58][59] When assayed in the human, the observed variability of the SP concentrations are large, and in some cases the assay methodology is questionable.[60] SP concentrations cannot yet be used to diagnose disease clinically or gauge disease severity. It is not yet known whether changes in concentration of SP or density of its receptors is the cause of any given disease, or an effect.

Blockade for diseases with a chronic immunological component

As increasingly documented, the SP-NK1R system induces or modulates many aspects of the immune response, including WBC production and activation, and cytokine expression,[61] Reciprocally, cytokines may induce expression of SP and its NK1R.[62][63] In this sense, for diseases in which a pro-inflammatory component has been identified or strongly suspected, and for which current treatments are absent or in need of improvement, abrogation of the SP-NK1 system continues to receive focus as a treatment strategy. Currently, the only completely developed method available in that regard is antagonism (blockade, inhibition) of the SP preferring receptor, i.e., by drugs known as neurokinin type 1 antagonists (also termed: SP antagonists, or tachykinin antagonists.) One such drug is aprepitant to prevent the nausea and vomiting that accompanies chemotherapy, typically for cancer. With the exception of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, the patho-physiological basis of many of the disease groups listed below, for which NK1RAs have been studied as a therapeutic intervention, are to varying extents hypothesized to be initiated or advanced by a chronic non-homeostatic inflammatory response.[17][64][65][66]

Dermatological disorders: eczema/psoriasis, chronic pruritus

High levels of BDNF and substance P have been found associated with increased itching in eczema.[67][68]

Infections: HIV-AIDS, measles, RSV, others

The role of SP in HIV-AIDS has been well-documented.[61] Doses of aprepitant greater than those tested to date are required for demonstration of full efficacy. Respiratory syncytial and related viruses appear to upregulate SP receptors, and rat studies suggest that NK1RAs may be useful in treating or limiting long term sequelae from such infections.[69][70]

Entamoeba histolytica is a unicellular parasitic protozoan that infects the lower gastrointestinal tract of humans. The symptoms of infection are diarrhea, constipation, and abdominal pain.[71][72] This protozoan was found to secrete serotonin[73] as well as substance P and neurotensin.[74]

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)/cystitis

Despite strong preclinical rationale,[75] efforts to demonstrate efficacy of SP antagonists in inflammatory disease have been unproductive. A study in women with IBS confirmed that an NK1RAs antagonist was anxiolytic.[76]

Chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting

In line with its role as a first line defense system, SP is released when toxicants or poisons come into contact with a range of receptors on cellular elements in the chemoreceptor trigger zone, located in the floor of the fourth ventricle of the brain (area postrema). Presumably, SP is released in or around the nucleus of the solitary tract upon integrated activity of dopamine, serotonin, opioid, and/or acetylcholine receptor signaling. NK1Rs are stimulated. In turn, a fairly complex reflex is triggered involving cranial nerves responsible for respiration, retroperistalsis, and general autonomic discharge. The actions of aprepitant are said to be entirely central, thus requiring passage of the drug into the central nervous system.[77] However, given that NK1Rs are unprotected by a blood brain barrier in the area postrema just adjacent to neuronal structures in the medulla, and the activity of sendide (the peptide based NK1RA) against cisplatin-induced emesis in the ferret,[78] it is likely that some peripheral exposure contributes to antiemetic effects, even if through vagal terminals in the clinical setting.

Other findings

Denervation supersensitivity

When the innervation to substance P nerve terminals is lost, post-synaptic cells compensate for the loss of adequate neurotransmitter by increasing the expression of post-synaptic receptors. This, ultimately, leads to a condition known as denervation supersensitivity as the post-synaptic nerves will become hypersensitive to any release of substance P into the synaptic cleft.

Aggression

Tachykinin / Substance P plays an evolutionarily conserved role in inducing aggressive behaviors.[79] In rodents and cats, activation of hypothalamic neurons which release Substance P induces aggressive behaviors (defensive biting and predatory attack).[80][81][82] Similarly, in fruit flies, tachykinin-releasing neurons have been implicated in aggressive behaviors (lunging).[83][84] In this context, male-specific tachykinin neurons control lunging behaviors that can be modulated by the amount of tachykinin release.[85]

References

- ↑ "Undecapeptide Definition & Meaning". Meriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/medical/undecapeptide.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Substance p". The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 33 (6): 555–76. Jun 2001. doi:10.1016/S1357-2725(01)00031-0. PMID 11378438.

- ↑ "Substance P: structure, function, and therapeutics". Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry 4 (1): 75–103. 2004. doi:10.2174/1568026043451636. PMID 14754378. http://www.bentham-direct.org/pages/content.php?CTMC%2F2004%2F00000004%2F00000001%2F0009R.SGM. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ↑ Reece, Jane B.; Campbell, Neil A. (2005). Biology, 7th Edition. San Francisco: Pearson, Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 9780805371468. OCLC 57368924. https://books.google.com/books?id=UgtOAQAAIAAJ.

- ↑ "Posttranslational modification of glycine-extended substance P by an alpha-amidating enzyme in cultured sensory neurons of dorsal root ganglia". Journal of Neuroscience Research 37 (1): 97–102. Jan 1994. doi:10.1002/jnr.490370113. PMID 7511706.

- ↑ "An unidentified depressor substance in certain tissue extracts". The Journal of Physiology 72 (1): 74–87. June 1931. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1931.sp002763. PMID 16994201.

- ↑ "Amino-acid sequence of substance P". Nature 232 (29): 86–87. July 1971. doi:10.1038/newbio232086a0. PMID 5285346.

- ↑ "Immunohistochemical localization of bombesin/gastrin-releasing peptide and substance P in primary sensory neurons". The Journal of Neuroscience 3 (10): 2021–9. Oct 1983. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-10-02021.1983. PMID 6194276.

- ↑ "Human substance P receptor (NK-1): organization of the gene, chromosome localization, and functional expression of cDNA clones". Biochemistry 30 (44): 10640–6. Nov 1991. doi:10.1021/bi00108a006. PMID 1657150.

- ↑ "The mammalian tachykinin receptors". General Pharmacology 26 (5): 911–44. Sep 1995. doi:10.1016/0306-3623(94)00292-U. PMID 7557266.

- ↑ "Delineation of the endocytic pathway of substance P and its seven-transmembrane domain NK1 receptor". Molecular Biology of the Cell 6 (5): 509–24. May 1995. doi:10.1091/mbc.6.5.509. PMID 7545030.

- ↑ "Localization of NK1 and NK3 receptors in guinea-pig brain". Regulatory Peptides 98 (1–2): 55–62. Apr 2001. doi:10.1016/S0167-0115(00)00228-7. PMID 11179779.

- ↑ "Neurokinin 1 receptor antagonism requires norepinephrine to increase serotonin function". European Neuropsychopharmacology 17 (5): 328–38. Apr 2007. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2006.07.004. PMID 16950604.

- ↑ "C/EBPbeta couples dopamine signalling to substance P precursor gene expression in striatal neurones". Journal of Neurochemistry 98 (5): 1390–9. Sep 2006. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03957.x. PMID 16771829.

- ↑ "Substance P: a regulatory neuropeptide for hematopoiesis and immune functions". Clinical Immunology and Immunopathology 85 (2): 129–33. Nov 1997. doi:10.1006/clin.1997.4446. PMID 9344694.

- ↑ "mRNA expression of tachykinins and tachykinin receptors in different human tissues". European Journal of Pharmacology 494 (2–3): 233–9. Jun 2004. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.05.016. PMID 15212980.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "The role of substance P in inflammatory disease". Journal of Cellular Physiology 201 (2): 167–80. Nov 2004. doi:10.1002/jcp.20061. PMID 15334652.

- ↑ "In vivo measurement of endothelium-dependent vasodilation with substance P in man". Herz 17 (5): 284–90. Oct 1992. PMID 1282120.

- ↑ "Neurokinin-1 receptor desensitization to consecutive microdialysis infusions of substance P in human skin". The Journal of Physiology 568 (Pt 3): 1047–56. Nov 2005. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2005.095372. PMID 16123103.

- ↑ "Immunoregulatory effects of neuropeptides. Stimulation of interleukin-2 production by substance p". Journal of Neuroimmunology 37 (1–2): 65–74. Mar 1992. doi:10.1016/0165-5728(92)90156-f. PMID 1372331.

- ↑ "Substance P induces secretion of immunomodulatory cytokines by human astrocytoma cells". Journal of Neuroimmunology 81 (1–2): 127–37. Jan 1998. doi:10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00167-7. PMID 9521614.

- ↑ "Absence of the SP/SP receptor circuitry in the substance P-precursor knockout mice or SP receptor, neurokinin (NK)1 knockout mice leads to an inhibited cytokine response in granulomas associated with murine Taenia crassiceps infection". The Journal of Parasitology 94 (6): 1253–8. Dec 2008. doi:10.1645/GE-1481.1. PMID 18576810.

- ↑ "Cytokine regulation of substance P expression in sympathetic neurons". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 88 (8): 3200–3. Apr 1991. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.8.3200. PMID 1707535. Bibcode: 1991PNAS...88.3200F.

- ↑ "Effect of substance P on cytokine production by human astrocytic cells and blood mononuclear cells: characterization of novel tachykinin receptor antagonists". FEBS Letters 399 (3): 321–5. Dec 1996. doi:10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01346-4. PMID 8985172.

- ↑ "Metalloproteinases and transforming growth factor-alpha mediate substance P-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and proliferation in human colonocytes". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 279 (44): 45519–27. Oct 2004. doi:10.1074/jbc.M408523200. PMID 15319441.

- ↑ "The neuropeptide substance P activates p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase resulting in IL-6 expression independently from NF-kappa B". Journal of Immunology 165 (10): 5606–11. Nov 2000. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5606. PMID 11067916.

- ↑ "Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) and their antagonists regulate spontaneous and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-induced proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine production". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 288 (7): 4878–90. Feb 2013. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.422410. PMID 23275336.

- ↑ "Potential role of the NK1 receptor antagonists in chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting". Supportive Care in Cancer 9 (5): 350–4. Jul 2001. doi:10.1007/s005200000199. PMID 11497388.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "Substance P in traumatic brain injury". Neurotrauma: New Insights into Pathology and Treatment. Progress in Brain Research. 161. 2007. pp. 97–109. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(06)61007-8. ISBN 9780444530172.

- ↑ "Altered nociception, analgesia and aggression in mice lacking the receptor for substance P". Nature 392 (6674): 394–7. Mar 1998. doi:10.1038/32904. PMID 9537323. Bibcode: 1998Natur.392..394D.

- ↑ "The role of substance P in stress and anxiety responses". Amino Acids 31 (3): 251–72. Oct 2006. doi:10.1007/s00726-006-0335-9. PMID 16820980.

- ↑ "Sequence-specific effects of neurokinin substance P on memory, reinforcement, and brain dopamine activity". Psychopharmacology 112 (2–3): 147–62. 1993. doi:10.1007/BF02244906. PMID 7532865.

- ↑ "Substance P is a promoter of adult neural progenitor cell proliferation under normal and ischemic conditions". Journal of Neurosurgery 107 (3): 593–9. Sep 2007. doi:10.3171/JNS-07/09/0593. PMID 17886560.

- ↑ Baloyannis S, Costa V, Deretzi G, Michmizos D. 1999. Intraventricular Administration of Substance P Increases the Dendritic Arborisation and the Synaptic Surfaces of Purkinje Cells in Rat's Cerebellum. International Journal of Neuroscience, 101(1-4):89-107. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3109/00207450008986495

- ↑ "Neurotransmitters in the CNS control of breathing". Respiration Physiology 101 (3): 219–30. Sep 1995. doi:10.1016/0034-5687(95)00045-F. PMID 8606995.

- ↑ "Substance P: transmitter of nociception (Minireview)". Endocrine Regulations 34 (4): 195–201. Dec 2000. PMID 11137976.

- ↑ Gorman, James, To Study Aggression, a Fight Club for Flies, The New York Times, February 4, 2014, page D5 of the New York edition

- ↑ Belilos, Andrew; Gray, Cortez; Sanders, Christie; Black, Destiny; Mays, Elizabeth; Richie, Christopher; Sengupta, Ayesha; Hake, Holly et al. (December 2023). "Nucleus accumbens local circuit for cue-dependent aversive learning". Cell Reports 42 (12): 113488. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2023.113488. PMID 37995189.

- ↑ "Central neurocircuitry associated with emesis". The American Journal of Medicine 111 (8 Suppl 8A): 106S–112S. Dec 2001. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00849-X. PMID 11749934.

- ↑ "Stimulation of epithelial cell growth by the neuropeptide substance P". Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 52 (4): 476–85. Aug 1993. doi:10.1002/jcb.240520411. PMID 7693729.

- ↑ "Neurotrophic and anhidrotic keratopathy treated with substance P and insulinlike growth factor 1". Archives of Ophthalmology 115 (7): 926–7. Jul 1997. doi:10.1001/archopht.1997.01100160096021. PMID 9230840.

- ↑ "Impact of substance P on cellular immunity". Journal of Biological Regulators and Homeostatic Agents 22 (2): 93–8. 2008. PMID 18597700. https://www.biolifesas.org/jbrha/JBR%20v22i2.pdf.

- ↑ "Substance P induces rapid and transient membrane blebbing in U373MG cells in a p21-activated kinase-dependent manner". PLOS ONE 6 (9): e25332. 2011. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025332. PMID 21966499. Bibcode: 2011PLoSO...625332M.

- ↑ "The NK-1 receptor: a new target in cancer therapy". Current Drug Targets 12 (6): 909–21. Jun 2011. doi:10.2174/138945011795528796. PMID 21226668.

- ↑ "[D-Arg1,D-Trp5,7,9,Leu11]substance P: a novel potent inhibitor of signal transduction and growth in vitro and in vivo in small cell lung cancer cells". Cancer Research 57 (1): 51–4. Jan 1997. PMID 8988040.

- ↑ "A new frontier in the treatment of cancer: NK-1 receptor antagonists". Current Medicinal Chemistry 17 (6): 504–16. 2010. doi:10.2174/092986710790416308. PMID 20015033.

- ↑ "Involvement of substance P and the NK-1 receptor in cancer progression". Peptides 48: 1–9. Oct 2013. doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2013.07.024. PMID 23933301.

- ↑ "Hepatoblastoma cells express truncated neurokinin-1 receptor and can be growth inhibited by aprepitant in vitro and in vivo". Journal of Hepatology 60 (5): 985–94. May 2014. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2013.12.024. PMID 24412605.

- ↑ "Serum levels of substance P are elevated in patients with sickle cell disease and increase further during vaso-occlusive crisis". Blood 92 (9): 3148–51. Nov 1998. doi:10.1182/blood.V92.9.3148. PMID 9787150.

- ↑ "Receptor binding sites for substance P, but not substance K or neuromedin K, are expressed in high concentrations by arterioles, venules, and lymph nodules in surgical specimens obtained from patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 85 (9): 3235–9. May 1988. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.9.3235. PMID 2834738. Bibcode: 1988PNAS...85.3235M.

- ↑ "Substance P as an immune modulator of anxiety". Neuroimmunomodulation 4 (1): 42–8. 1997. doi:10.1159/000097314. PMID 9326744.

- ↑ "Elevated cerebrospinal fluid substance p concentrations in posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression". The American Journal of Psychiatry 163 (4): 637–43. Apr 2006. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.4.637. PMID 16585438.

- ↑ "The role of substance P in depression: therapeutic implications". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 4 (1): 21–9. Mar 2002. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2002.4.1/mschwarz. PMID 22033776.

- ↑ "New insights into the antidepressant actions of substance P (NK1 receptor) antagonists". Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology 80 (5): 489–94. May 2002. doi:10.1139/y02-048. PMID 12056558.

- ↑ "Elevated CSF levels of substance P and high incidence of Raynaud phenomenon in patients with fibromyalgia: new features for diagnosis". Pain 32 (1): 21–6. Jan 1988. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(88)90019-X. PMID 2448729.

- ↑ "Substance P in the serum of patients with rheumatoid arthritis". Revue du Rhumatisme 64 (1): 18–21. Jan 1997. PMID 9051855.

- ↑ "Elevated substance P levels in HIV-infected men". AIDS 15 (15): 2043–5. Oct 2001. doi:10.1097/00002030-200110190-00019. PMID 11600835.

- ↑ "The role of tachykinins via NK1 receptors in progression of human gliomas". Life Sciences 67 (9): 985–1001. 2000. doi:10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00692-5. PMID 10954033.

- ↑ "Increased expression of preprotachykinin-I and neurokinin receptors in human breast cancer cells: implications for bone marrow metastasis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97 (1): 388–93. Jan 2000. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.1.388. PMID 10618428. Bibcode: 2000PNAS...97..388S.

- ↑ "Measurement of plasma-derived substance P: biological, methodological, and statistical considerations". Clinical and Vaccine Immunology 13 (11): 1197–203. Nov 2006. doi:10.1128/CVI.00174-06. PMID 16971517.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 "Substance P and neurokinin-1 receptor modulation of HIV". Journal of Neuroimmunology 157 (1–2): 48–55. Dec 2004. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.08.022. PMID 15579279.

- ↑ "Substance P enhances cytokine-induced vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) expression on cultured rheumatoid fibroblast-like synoviocytes". Clinical and Experimental Immunology 113 (2): 269–75. Aug 1998. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00621.x. PMID 9717978.

- ↑ "Substance P induces TNF-alpha and IL-6 production through NF kappa B in peritoneal mast cells". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 1643 (1–3): 75–83. Dec 2003. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2003.09.003. PMID 14654230.

- ↑ "Neurokinin-1 receptor: functional significance in the immune system in reference to selected infections and inflammation". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1217 (1): 83–95. Jan 2011. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05826.x. PMID 21091716. Bibcode: 2011NYASA1217...83D.

- ↑ "Substance P and its receptors -- a potential target for novel medicines in malignant brain tumour therapies (mini-review)". Folia Neuropathologica 45 (3): 99–107. 2007. PMID 17849359.

- ↑ van der Hart MG (2009). Substance P and the Neurokinin 1 receptor: From behavior to bioanalysis (Ph.D.). University of Groningen. ISBN 978-90-367-3874-3.

- ↑ "'Blood chemicals link' to eczema". Health. BBC News. 2007-08-26. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/6962450.stm.

- ↑ "Pathophysiology of nocturnal scratching in childhood atopic dermatitis: the role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and substance P". The British Journal of Dermatology 157 (5): 922–5. Nov 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08149.x. PMID 17725670.

- ↑ "Exaggerated neurogenic inflammation and substance P receptor upregulation in RSV-infected weanling rats". American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology 24 (2): 101–7. Feb 2001. doi:10.1165/ajrcmb.24.2.4264. PMID 11159042.

- ↑ "Neural mechanisms of respiratory syncytial virus-induced inflammation and prevention of respiratory syncytial virus sequelae". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 163 (3 Pt 2): S18-21. Mar 2001. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.163.supplement_1.2011113. PMID 11254547.

- ↑ "[Chronic recurrent intestinal amebiasis in Israel (author's transl)]" (in de). Leber, Magen, Darm 9 (4): 175–9. Aug 1979. PMID 491812.

- ↑ "Irritable bowel syndrome: a review on the role of intestinal protozoa and the importance of their detection and diagnosis". International Journal for Parasitology 37 (1): 11–20. Jan 2007. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.09.009. PMID 17070814.

- ↑ "Entamoeba histolytica causes intestinal secretion: role of serotonin". Science 221 (4612): 762–4. Aug 1983. doi:10.1126/science.6308760. PMID 6308760. Bibcode: 1983Sci...221..762M.

- ↑ "Chapter 8: Secretory Hormones of Entamoeba histolytica". Microbial Toxins and Diarrhoeal Disease. Ciba Found. Symp.. 112. 1985. pp. 139–54. doi:10.1002/9780470720936.ch8.

- ↑ "Tachykinins and their receptors: contributions to physiological control and the mechanisms of disease". Physiol. Rev. 94 (1): 265–301. 2014. doi:10.1152/physrev.00031.2013. PMID 24382888.

- ↑ "Neurokinin-1-receptor antagonism decreases anxiety and emotional arousal circuit response to noxious visceral distension in women with irritable bowel syndrome: a pilot study". Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 35 (3): 360–367. 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04958.x. PMID 22221140.

- ↑ "Brain penetration of aprepitant, a substance P receptor antagonist, in ferrets". Drug Metabolism and Disposition 31 (6): 785–91. Jun 2003. doi:10.1124/dmd.31.6.785. PMID 12756213.

- ↑ "Neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists in the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting". British Journal of Anaesthesia 103 (1): 7–13. Jul 2009. doi:10.1093/bja/aep125. PMID 19454547.

- ↑ "Tachykinins: Neuropeptides That Are Ancient, Diverse, Widespread and Functionally Pleiotropic". Frontiers in Neuroscience 13: 1262. 2019-11-20. doi:10.3389/fnins.2019.01262. PMID 31824255.

- ↑ "Neurotransmitters regulating defensive rage behavior in the cat". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. The neurobiology of defensive behavior in animals 21 (6): 733–742. November 1997. doi:10.1016/S0149-7634(96)00056-5. PMID 9415898.

- ↑ "Substance P neurotransmission and violent aggression: the role of tachykinin NK(1) receptors in the hypothalamic attack area". European Journal of Pharmacology 611 (1–3): 35–43. June 2009. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.03.050. PMID 19344710.

- ↑ "The involvement of substance P in the induction of aggressive behavior". Peptides 30 (8): 1586–1591. August 2009. doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2009.05.001. PMID 19442694.

- ↑ "Neuromodulation and Strategic Action Choice in Drosophila Aggression". Annual Review of Neuroscience 40 (1): 51–75. July 2017. doi:10.1146/annurev-neuro-072116-031240. PMID 28375770.

- ↑ Gorman, James (2014-02-03). "To Study Aggression, a Fight Club for Flies-US". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/04/science/to-study-aggression-a-fight-club-for-flies.html.

- ↑ "Tachykinin-expressing neurons control male-specific aggressive arousal in Drosophila" (in English). Cell 156 (1–2): 221–235. January 2014. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.045. PMID 24439378.

External links

- Russell J (2001-09-14). "Neurochemical Substance P is Key to Understanding Pain Process". Fibromyalgia Library. ProHealth.com. http://www.fibromyalgiasupport.com/library/showarticle.cfm/id/3097.

- Fight Club for Flies video, Science Take, New York Times, February 3, 2014

|