Chemistry:Methylglyoxal

|

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

2-Oxopropanal | |||

| Other names

Pyruvaldehyde

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| 3DMet | |||

| 906750 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| KEGG | |||

| MeSH | Methylglyoxal | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C3H4O2 | |||

| Molar mass | 72.063 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Yellow liquid | ||

| Density | 1.046 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | 25 °C (77 °F; 298 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 72 °C (162 °F; 345 K) | ||

| Hazards | |||

| GHS pictograms |

| ||

| GHS Signal word | Danger | ||

| H290, H302, H315, H317, H318, H319, H335, H341 | |||

| P201, P202, P234, P261, P264, P270, P271, P272, P280, P281, P301+312, P302+352, P304+340, P305+351+338, P308+313, P310, P312, P321, P330, P332+313, P333+313, P337+313, P362, P363, P390 | |||

| Related compounds | |||

Related compounds

|

|||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

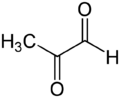

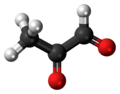

Methylglyoxal (MGO) is the organic compound with the formula CH3C(O)CHO. It is a reduced derivative of pyruvic acid. It is a reactive compound that is implicated in the biology of diabetes. Methylglyoxal is produced industrially by degradation of carbohydrates using overexpressed methylglyoxal synthase.[1]

Chemical structure

Gaseous methylglyoxal has two carbonyl groups, an aldehyde and a ketone. In the presence of water, it exists as hydrates and oligomers. The formation of these hydrates is indicative of the high reactivity of MGO, which is relevant to its biological behavior.[2]

Biochemistry

Biosynthesis and biodegradation

In organisms, methylglyoxal is formed as a side-product of several metabolic pathways.[3] Methylglyoxal mainly arises as side products of glycolysis involving glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate and dihydroxyacetone phosphate. It is also thought to arise via the degradation of acetone and threonine.[4] Illustrative of the myriad pathways to MGO, aristolochic acid caused 12-fold increase of methylglyoxal from 18 to 231 μg/mg of kidney protein in poisoned mice.[5] It may form from 3-aminoacetone, which is an intermediate of threonine catabolism, as well as through lipid peroxidation. However, the most important source is glycolysis. Here, methylglyoxal arises from nonenzymatic phosphate elimination from glyceraldehyde phosphate and dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP), two intermediates of glycolysis. This conversion is the basis of a potential biotechnological route to the commodity chemical 1,2-propanediol.[6]

Since methylglyoxal is highly cytotoxic, several detoxification mechanisms have evolved. One of these is the glyoxalase system. Methylglyoxal is detoxified by glutathione. Glutathione reacts with methylglyoxal to give a hemithioacetal, which converted into S-D-lactoyl-glutathione by glyoxalase I.[7] This thioester is hydrolyzed to D-lactate by glyoxalase II.[8]

Biochemical function

Methylglyoxal is involved in the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs).[4] In this process, methylglyoxal reacts with free amino groups of lysine and arginine and with thiol groups of cysteine forming AGEs. Histones are also heavily susceptible to modification by methylglyoxal and these modifications are elevated in breast cancer.[9][10]

DNA damages are induced by reactive carbonyls, principally methylglyoxal and glyoxal, at a frequency similar to that of oxidative DNA damages.[12] Such damage, referred to as DNA glycation, can cause mutation, breaks in DNA and cytotoxicity.[12] In humans, a protein DJ-1 (also named PARK7), has a key role in the repair of glycated DNA bases.

Biomedical aspects

Due to increased blood glucose levels, methylglyoxal has higher concentrations in diabetics and has been linked to arterial atherogenesis. Damage by methylglyoxal to low-density lipoprotein through glycation causes a fourfold increase of atherogenesis in diabetics.[13] Methylglyoxal binds directly to the nerve endings and by that increases the chronic extremity soreness in diabetic neuropathy.[14][15]

Occurrence, other

Methylglyoxal is a component of some kinds of honey, including manuka honey; it appears to have activity against E. coli and S. aureus and may help prevent formation of biofilms formed by P. aeruginosa.[16]

Research suggests that methylglyoxal contained in honey does not cause an increased formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in healthy persons.[17][18]

See also

- Dicarbonyl

- 1,2-Dicarbonyl, methylglyoxal can be classified as an 1,2-dicarbonyl

References

- ↑ Lichtenthaler, Frieder W. (2010). "Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.n05_n07.

- ↑ Loeffler, Kirsten W.; Koehler, Charles A.; Paul, Nichole M.; De Haan, David O. (2006). "Oligomer Formation in Evaporating Aqueous Glyoxal and Methyl Glyoxal Solutions". Environmental Science & Technology 40 (20): 6318–23. doi:10.1021/es060810w. PMID 17120559. Bibcode: 2006EnST...40.6318L.

- ↑ "Methylglyoxal and regulation of its metabolism in microorganisms". Adv. Microb. Physiol.. Advances in Microbial Physiology 37: 177–227. 1995. doi:10.1016/S0065-2911(08)60146-0. ISBN 978-0-12-027737-7. PMID 8540421.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Bellier, Justine; Nokin, Marie-Julie; Lardé, Eva; Karoyan, Philippe; Peulen, Olivier; Castronovo, Vincent; Bellahcène, Akeila (2019). "Methylglyoxal, a Potent Inducer of AGEs, Connects between Diabetes and Cancer". Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 148: 200–211. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2019.01.002. PMID 30664892.

- ↑ Li, YC; Tsai, SH; Chen, SM; Chang, YM; Huang, TC; Huang, YP; Chang, CT; Lee, JA (2012). "Aristolochic acid-induced accumulation of methylglyoxal and Nε-(carboxymethyl)lysine: an important and novel pathway in the pathogenic mechanism for aristolochic acid nephropathy". Biochem Biophys Res Commun 423 (4): 832–7. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.06.049. PMID 22713464.

- ↑ Sullivan, Carl J.; Kuenz, Anja; Vorlop, Klaus‐Dieter (2018). "Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a22_163.pub2.

- ↑ Thornalley PJ (2003). "Glyoxalase I—structure, function and a critical role in the enzymatic defence against glycation". Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31 (Pt 6): 1343–8. doi:10.1042/BST0311343. PMID 14641060.

- ↑ Vander Jagt DL (1993). "Glyoxalase II: molecular characteristics, kinetics and mechanism". Biochem. Soc. Trans. 21 (2): 522–7. doi:10.1042/bst0210522. PMID 8359524.

- ↑ "Methylglyoxal-derived posttranslational arginine modifications are abundant histone marks". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115 (37): 9228–33. September 2018. doi:10.1073/pnas.1802901115. PMID 30150385. Bibcode: 2018PNAS..115.9228G.

- ↑ "Reversible histone glycation is associated with disease-related changes in chromatin architecture". Nat Commun 10 (1): 1289. March 2019. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09192-z. PMID 30894531. Bibcode: 2019NatCo..10.1289Z.

- ↑ Oya, Tomoko; Hattori, Nobutaka; Mizuno, Yoshikuni; Miyata, Satoshi; Maeda, Sakan; Osawa, Toshihiko; Uchida, Koji (1999). "Methylglyoxal Modification of Protein". Journal of Biological Chemistry 274 (26): 18492–502. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.26.18492. PMID 10373458.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Richarme G, Liu C, Mihoub M, Abdallah J, Leger T, Joly N, Liebart JC, Jurkunas UV, Nadal M, Bouloc P, Dairou J, Lamouri A. Guanine glycation repair by DJ-1/Park7 and its bacterial homologs. Science. 2017 Jul 14;357(6347):208-211. doi: 10.1126/science.aag1095. Epub 2017 Jun 8. PMID: 28596309

- ↑ Rabbani N; Godfrey, L; Xue, M; Shaheen, F; Geoffrion, M; Milne, R; Thornalley, PJ (May 26, 2011). "Glycation of LDL by methylglyoxal increases arterial atherogenicity. A possible contributor to increased risk of cardiovascular disease in diabetes". Diabetes 60 (7): 1973–80. doi:10.2337/db11-0085. PMID 21617182.

- ↑ Spektrum: Diabetische Neuropathie: Methylglyoxal verstärkt den Schmerz: DAZ.online. Deutsche-apotheker-zeitung.de (2012-05-21). Retrieved on 2012-06-11.

- ↑ Bierhaus, Angelika; Fleming, Thomas; Stoyanov, Stoyan; Leffler, Andreas; Babes, Alexandru; Neacsu, Cristian; Sauer, Susanne K; Eberhardt, Mirjam et al. (2012). "Methylglyoxal modification of Nav1.8 facilitates nociceptive neuron firing and causes hyperalgesia in diabetic neuropathy". Nature Medicine 18 (6): 926–33. doi:10.1038/nm.2750. PMID 22581285.

- ↑ Israili, ZH (2014). "Antimicrobial properties of honey.". American Journal of Therapeutics 21 (4): 304–23. doi:10.1097/MJT.0b013e318293b09b. PMID 23782759.

- ↑ "Demonstrating the safety of manuka honey UMF® 20+ in a human clinical trial with healthy individuals". Br J Nutr 103 (7): 1023–8. April 2010. doi:10.1017/S0007114509992777. PMID 20064284.

- ↑ "Metabolic transit of dietary methylglyoxal". J Agric Food Chem 61 (43): 10253–60. October 2013. doi:10.1021/jf304946p. PMID 23451712.

{{Navbox | name = GABA receptor modulators | title = GABA receptor modulators | state = collapsed | bodyclass = hlist | groupstyle = text-align:center;

| group1 = Ionotropic | list1 = {{Navbox|subgroup | groupstyle = text-align:center | groupwidth = 5em

| group1 = GABAA | list1 =

- Agonists: (+)-Catechin

- Bamaluzole

- Barbiturates (e.g., phenobarbital)

- BL-1020

- DAVA

- Dihydromuscimol

- GABA

- Gabamide

- GABOB

- Gaboxadol (THIP)

- Homotaurine (tramiprosate, 3-APS)

- Ibotenic acid

- iso-THAZ

- iso-THIP

- Isoguvacine

- Isomuscimol

- Isonipecotic acid

- Kojic amine

- Lignans (e.g., honokiol)

- Methylglyoxal

- Monastrol

- Muscimol

- Nefiracetam

- Neuroactive steroids (e.g., allopregnanolone)

- Org 20599

- PF-6372865

- Phenibut

- Picamilon

- P4S

- Progabide

- Propofol

- Quisqualamine

- SL-75102

- TACA

- TAMP

- Terpenoids (e.g., borneol)

- Thiomuscimol

- Tolgabide

- ZAPA

- Positive modulators (abridged; see here for a full list): α-EMTBL

- Alcohols (e.g., ethanol)

- Anabolic steroids

- Avermectins (e.g., ivermectin)

- Barbiturates (e.g., phenobarbital)

- Benzodiazepines (e.g., diazepam)

- Bromide compounds (e.g., potassium bromide)

- Carbamates (e.g., meprobamate)

- Carbamazepine

- Chloralose

- Chlormezanone

- Clomethiazole

- Dihydroergolines (e.g., ergoloid (dihydroergotoxine))

- Etazepine

- Etifoxine

- Fenamates (e.g., mefenamic acid)

- Flavonoids (e.g., apigenin, hispidulin)

- Fluoxetine

- Flupirtine

- Imidazoles (e.g., etomidate)

- Kava constituents (e.g., kavain)<!--PMID: 9776662-->

- Lanthanum

- Loreclezole

- Monastrol

- Neuroactive steroids (e.g., allopregnanolone, [[Chemistry:Cholecholesterol]], THDOC)

- Niacin

- Nicotinamide (niacinamide)

- Nonbenzodiazepines (e.g., β-carbolines (e.g., [[abecarnil), cyclopyrrolones (e.g., zopiclone), imidazopyridines (e.g., zolpidem), pyrazolopyrimidines (e.g., zaleplon))

- Norfluoxetine

- Petrichloral

- Phenols (e.g., propofol)

- Phenytoin

- Piperidinediones (e.g., glutethimide)

- Propanidid

- Pyrazolopyridines (e.g., etazolate)

- Quinazolinones (e.g., methaqualone)

- Retigabine (ezogabine)

- ROD-188

- Skullcap constituents (e.g., baicalin)

- Stiripentol

- Sulfonylalkanes (e.g., sulfonmethane (sulfonal))

- Topiramate

- Valerian constituents (e.g., valerenic acid)

- Volatiles/gases (e.g., chloral hydrate, chloroform, [[Chemistry:Diethyl diethyl ether, Parparaldehyde]], sevoflurane)

- Antagonists: Bicuculline

- Coriamyrtin

- Dihydrosecurinine

- Gabazine (SR-95531)

- Hydrastine

- Hyenachin (mellitoxin)

- PHP-501

- Pitrazepin

- Securinine

- Sinomenine

- SR-42641

- SR-95103

- Thiocolchicoside

- Tutin

- Negative modulators: 1,3M1B

- 3M2B

- 11-Ketoprogesterone

- 17-Phenylandrostenol

- α5IA (LS-193,268)

- β-CCB

- β-CCE

- β-CCM

- β-CCP

- β-EMGBL

- Anabolic steroids

- Amiloride

- Anisatin

- β-Lactams (e.g., penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems)

- Basmisanil

- Bemegride

- Bicyclic phosphates (TBPS, TBPO, IPTBO)

- BIDN

- Bilobalide

- Bupropion

- CHEB

- Chlorophenylsilatrane

- Cicutoxin

- Cloflubicyne

- Cyclothiazide

- DHEA

- DHEA-S

- Dieldrin

- (+)-DMBB

- DMCM

- DMPC

- EBOB

- Etbicyphat

- FG-7142 (ZK-31906)

- Fiproles (e.g., fipronil)

- Flavonoids (e.g., amentoflavone, oroxylin A)

- Flumazenil

- Fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin)

- Flurothyl

- Furosemide

- Golexanolone

- Iomazenil (123I)

- IPTBO

- Isopregnanolone (sepranolone)

- L-655,708

- Laudanosine

- Leptazol

- Lindane

- MaxiPost

- Morphine

- Morphine-3-glucuronide

- MRK-016

- Naloxone

- Naltrexone

- Nicardipine

- Nonsteroidal antiandrogens (e.g., [[apalutamide, [[Chemistry:Bicalutbicalutamide, Enzalutenzalutamide, Chemistry:Flutamide|flut]]amide]], nilutamide)

- Oenanthotoxin

- Pentylenetetrazol (pentetrazol)

- Phenylsilatrane

- Picrotoxin (i.e., picrotin, picrotoxinin and dihydropicrotoxinin)

- Pregnenolone sulfate

- Propybicyphat

- PWZ-029

- Radequinil

- Ro 15-4513

- Ro 19-4603

- RO4882224

- RO4938581

- Sarmazenil

- SCS

- Suritozole

- TB-21007

- TBOB

- TBPS

- TCS-1105

- Terbequinil

- TETS

- Thujone

- U-93631

- Zinc

- ZK-93426

| group2 = GABAA-ρ | list2 =

- Agonists: BL-1020

- CACA

- CAMP

- Homohypotaurine

- GABA

- GABOB

- Ibotenic acid

- Isoguvacine

- Muscimol

- N4-Chloroacetylcytosine arabinoside

- Picamilon

- Progabide

- TACA

- TAMP

- Thiomuscimol

- Tolgabide

- Positive modulators: Allopregnanolone

- Alphaxolone

- ATHDOC

- Lanthanides

- Antagonists: (S)-2-MeGABA

- (S)-4-ACPBPA

- (S)-4-ACPCA

- 2-MeTACA

- 3-APMPA

- 4-ACPAM

- 4-GBA

- cis-3-ACPBPA

- CGP-36742 (SGS-742)

- DAVA

- Gabazine (SR-95531)

- Gaboxadol (THIP)

- I4AA

- Isonipecotic acid

- Loreclezole

- P4MPA

- P4S

- SKF-97541

- SR-95318

- SR-95813

- TPMPA

- trans-3-ACPBPA

- ZAPA

- Negative modulators: 5α-Dihydroprogesterone

- Bilobalide

- Loreclezole

- Picrotoxin (picrotin, picrotoxinin)

- Pregnanolone

- ROD-188

- THDOC

- Zinc

}}

| group2 = Metabotropic

| list2 =

| below =

- See also

- Receptor/signaling modulators

- GABAA receptor positive modulators

- GABA metabolism/transport modulators

}}

|