Astronomy:Space station

Template:Space station size comparison A space station (or orbital station) is a spacecraft which remains in orbit and hosts humans for extended periods of time. It is therefore an artificial satellite featuring habitation facilities. The purpose of maintaining a space station varies depending on the program. Most often space stations have been research stations, but they have also served military or commercial uses, such as hosting space tourists.

Space stations have been hosting the only continuous presence of humans in space. The first space station was Salyut 1 (1971), hosting the first crew, of the ill-fated Soyuz 11. Consecutively space stations have been operated since Skylab (1973) and occupied since 1987 with the Salyut successor Mir. Uninterrupted human presence in orbital space through space stations has been sustained since the operational transition from the Mir to the International Space Station (ISS), with the latter's first occupation in 2000.

Currently there are two fully operational space stations – the ISS and China's Tiangong Space Station (TSS), which have been occupied since October 2000 with Expedition 1 and since June 2022 with Shenzhou 14. The highest number of people at the same time on one space station has been 13, first achieved with the eleven day docking to the ISS of the 127th Space Shuttle mission in 2009. The present record for most people on all space stations at the same time has been 17, first reached on May 30, 2023, with 11 people on the ISS and 6 on the TSS.[1]

Space stations are often modular, featuring docking ports, through which they are built and maintained, allowing the joining or movement of modules and the docking of other spacecrafts for the exchange of people, supplies and tools. While space stations generally do not leave their orbit, they do feature thrusters for station keeping.

History

Early concepts

The first mention of anything resembling a space station occurred in Edward Everett Hale's 1868 "The Brick Moon".[2] The first to give serious, scientifically grounded consideration to space stations were Konstantin Tsiolkovsky and Hermann Oberth about two decades apart in the early 20th century.[3]

(Legend: Achs-Körper: axle body. Aufzugschacht: elevator shaft. Treppenschacht: stairwell. Verdampfungsrohr: boiler pipe).

In 1929, Herman Potočnik's The Problem of Space Travel was published, the first to envision a "rotating wheel" space station to create artificial gravity.[2] Conceptualized during the Second World War, the "sun gun" was a theoretical orbital weapon orbiting Earth at a height of 8,200 kilometres (5,100 mi). No further research was ever conducted.[4] In 1951, Wernher von Braun published a concept for a rotating wheel space station in Collier's Weekly, referencing Potočnik's idea. However, development of a rotating station was never begun in the 20th century.[3]

First advances and precursors

The first human flew to space and concluded the first orbit on April 12, 1961, with Vostok 1.

The Apollo program had in its early planning instead of a lunar landing a crewed lunar orbital flight and an orbital laboratory station in orbit of Earth, at times called Project Olympus, as two different possible program goals, until the Kennedy administration sped ahead and made the Apollo program focus on what was originally planned to come after it, the lunar landing. The Project Olympus space station, or orbiting laboratory of the Apollo program, was proposed as an in-space unfolded structure with the Apollo command and service module docking.[5] While never realized, the Apollo command and service module would perform docking maneuvers and eventually become a lunar orbiting module which was used for station-like purposes.

But before that the Gemini program paved the way and achieved the first space rendezvous (undocked) with Gemini 6 and Gemini 7 in 1965. Subsequently in 1966 Neil Armstrong performed on Gemini 8 the first ever space docking, while in 1967 Kosmos 186 and Kosmos 188 were the first spacecrafts that docked automatically.

In January 1969, Soyuz 4 and Soyuz 5 performed the first docked, but not internal, crew transfer, and in March, Apollo 9 performed the first ever internal transfer of astronauts between two docked spaceships.

Salyut, Almaz and Skylab

In 1971, the Soviet Union developed and launched the world's first space station, Salyut 1.[6] The Almaz and Salyut series were eventually joined by Skylab, Mir, and Tiangong-1 and Tiangong-2. The hardware developed during the initial Soviet efforts remains in use, with evolved variants comprising a considerable part of the ISS, orbiting today. Each crew member stays aboard the station for weeks or months but rarely more than a year.

Early stations were monolithic designs that were constructed and launched in one piece, generally containing all their supplies and experimental equipment. A crew would then be launched to join the station and perform research. After the supplies had been consumed, the station was abandoned.[6]

The first space station was Salyut 1, which was launched by the Soviet Union on April 19, 1971. The early Soviet stations were all designated "Salyut", but among these, there were two distinct types: civilian and military. The military stations, Salyut 2, Salyut 3, and Salyut 5, were also known as Almaz stations.[7]

The civilian stations Salyut 6 and Salyut 7 were built with two docking ports, which allowed a second crew to visit, bringing a new spacecraft with them; the Soyuz ferry could spend 90 days in space, at which point it needed to be replaced by a fresh Soyuz spacecraft.[8] This allowed for a crew to man the station continually. The American Skylab (1973–1979) was also equipped with two docking ports, like second-generation stations, but the extra port was never used. The presence of a second port on the new stations allowed Progress supply vehicles to be docked to the station, meaning that fresh supplies could be brought to aid long-duration missions. This concept was expanded on Salyut 7, which "hard docked" with a TKS tug shortly before it was abandoned; this served as a proof of concept for the use of modular space stations. The later Salyuts may reasonably be seen as a transition between the two groups.[7]

Mir

Unlike previous stations, the Soviet space station Mir had a modular design; a core unit was launched, and additional modules, generally with a specific role, were later added. This method allows for greater flexibility in operation, as well as removing the need for a single immensely powerful launch vehicle. Modular stations are also designed from the outset to have their supplies provided by logistical support craft, which allows for a longer lifetime at the cost of requiring regular support launches.[9]

International Space Station

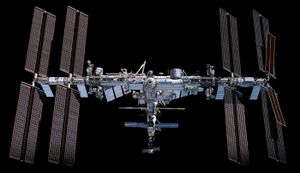

The ISS is divided into two main sections, the Russian Orbital Segment (ROS) and the US Orbital Segment (USOS). The first module of the ISS, Zarya, was launched in 1998.[10]

The Russian Orbital Segment's "second-generation" modules were able to launch on Proton, fly to the correct orbit, and dock themselves without human intervention.[11] Connections are automatically made for power, data, gases, and propellants. The Russian autonomous approach allows the assembly of space stations prior to the launch of crew.

The Russian "second-generation" modules are able to be reconfigured to suit changing needs. As of 2009, RKK Energia was considering the removal and reuse of some modules of the ROS on the Orbital Piloted Assembly and Experiment Complex after the end of mission is reached for the ISS.[12] However, in September 2017, the head of Roscosmos said that the technical feasibility of separating the station to form OPSEK had been studied, and there were now no plans to separate the Russian segment from the ISS.[13]

In contrast, the main US modules launched on the Space Shuttle and were attached to the ISS by crews during EVAs. Connections for electrical power, data, propulsion, and cooling fluids are also made at this time, resulting in an integrated block of modules that is not designed for disassembly and must be deorbited as one mass.[14]

Axiom Station is a planned commercial space station that will begin as a single module docked to the ISS. Axiom Space gained NASA approval for the venture in January 2020. The first module, the Payload Power Transfer Module (PPTM), is expected to be launched to the ISS no earlier than 2027.[15] PPTM will remain at the ISS until the launch of Axiom's Habitat One (Hab-1) module about one year later, after which it will detach from the ISS to join with Hab-1.[15]

Tiangong program

China's first space laboratory, Tiangong-1 was launched in September 2011.[16] The uncrewed Shenzhou 8 then successfully performed an automatic rendezvous and docking in November 2011. The crewed Shenzhou 9 then docked with Tiangong-1 in June 2012, followed by the crewed Shenzhou 10 in 2013. According to the China Manned Space Engineering Office, Tiangong-1 reentered over the South Pacific Ocean, northwest of Tahiti, on 2 April 2018 at 00:15 UTC.[17][18]

A second space laboratory Tiangong-2 was launched in September 2016, while a plan for Tiangong-3 was merged with Tiangong-2.[19] The station made a controlled reentry on 19 July 2019 and burned up over the South Pacific Ocean.[20]

The Tiangong Space Station (Chinese: 天宫; pinyin: Tiāngōng; literally: 'Heavenly Palace'), the first module of which was launched on 29 April 2021,[21] is in low Earth orbit, 340 to 450 kilometres above the Earth at an orbital inclination of 42° to 43°. The core module was extended in 2022 with two laboratory modules, bringing the total station capacity to six crew members. The station was completed on 5 November 2022.[22][23][24]

Planned projects

Architecture

Two types of space stations have been flown: monolithic and modular. Monolithic stations consist of a single vehicle and are launched by one rocket. Modular stations consist of two or more separate vehicles that are launched independently and docked on orbit. Modular stations are currently preferred due to lower costs and greater flexibility.[25][26]

A space station is a complex vehicle that must incorporate many interrelated subsystems, including structure, electrical power, thermal control, attitude determination and control, orbital navigation and propulsion, automation and robotics, computing and communications, environmental and life support, crew facilities, and crew and cargo transportation. Stations must serve a useful role, which drives the capabilities required.[citation needed]

Orbit and purpose

Materials

Space stations are made from durable materials that have to weather space radiation, internal pressure, micrometeoroids, thermal effects of the sun and cold temperatures for long periods of time. They are typically made from stainless steel, titanium and high-quality aluminum alloys, with layers of insulation such as Kevlar as a ballistics shield protection.[27]

The International Space Station (ISS) has a single inflatable module, the Bigelow Expandable Activity Module, which was installed in April 2016 after being delivered to the ISS on the SpaceX CRS-8 resupply mission.[28][29] This module, based on NASA research in the 1990s, weighs 1,400 kilograms (3,100 lb) and was transported while compressed before being attached to the ISS by the space station arm and inflated to provide a 16 cubic metres (21 cu yd) volume. Whilst it was initially designed for a 2 year lifetime it was still attached and being used for storage in August 2022.[30][31]

Construction

- Salyut 1 – first space station, launched in 1971

- Skylab – launched in a single launch in May 1973

- Mir – first modular space station assembled in orbit

- International Space Station – modular space station assembled in orbit

- Tiangong space station – Chinese space station

Habitability

The space station environment presents a variety of challenges to human habitability, including short-term problems such as the limited supplies of air, water, and food and the need to manage waste heat, and long-term ones such as weightlessness and relatively high levels of ionizing radiation. These conditions can create long-term health problems for space-station inhabitants, including muscle atrophy, bone deterioration, balance disorders, eyesight disorders, and elevated risk of cancer.[32]

Future space habitats may attempt to address these issues, and could be designed for occupation beyond the weeks or months that current missions typically last. Possible solutions include the creation of artificial gravity by a rotating structure, the inclusion of radiation shielding, and the development of on-site agricultural ecosystems. Some designs might even accommodate large numbers of people, becoming essentially "cities in space" where people would reside semi-permanently.[33]

Molds that develop aboard space stations can produce acids that degrade metal, glass, and rubber. Despite an expanding array of molecular approaches for detecting microorganisms, rapid and robust means of assessing the differential viability of the microbial cells, as a function of phylogenetic lineage, remain elusive.[34]

Power

Like uncrewed spacecraft close to the Sun, space stations in the inner Solar System generally rely on solar panels to obtain power.[35]

Life support

Space station air and water is brought up in spacecraft from Earth before being recycled. Supplemental oxygen can be supplied by a solid fuel oxygen generator.[36]

Communications

Military

The last military-use space station was the Soviet Salyut 5, which was launched under the Almaz program and orbited between 1976 and 1977.[37][38][39]

Occupation

Space stations have harboured so far the only long-duration direct human presence in space. After the first station, Salyut 1 (1971), and its tragic Soyuz 11 crew, space stations have been operated consecutively since Skylab (1973–1974), having allowed a progression of long-duration direct human presence in space. Long-duration resident crews have been joined by visiting crews since 1977 (Salyut 6), and stations have been occupied by consecutive crews since 1987 with the Salyut successor Mir. Uninterrupted occupation of stations has been achieved since the operational transition from the Mir to the ISS, with its first occupation in 2000. The ISS has hosted the highest number of people in orbit at the same time, reaching 13 for the first time during the eleven day docking of STS-127 in 2009.[40]

The duration record for a single spaceflight is 437.75 days, set by Valeri Polyakov aboard Mir from 1994 to 1995.[41] As of 2021[update], four cosmonauts have completed single missions of over a year, all aboard Mir.

Operations

Resupply and crew vehicles

Many spacecraft are used to dock with the space stations. Soyuz flight T-15 in March to July 1986 was the first and as of 2016, only spacecraft to visit two different space stations, Mir and Salyut 7.[42]

International Space Station

The International Space Station has been supported by many different spacecraft.

- Future

- Current

- Northrop Grumman Cygnus (2013–present)[47][48]

- New Space-Station Resupply Vehicle (HTV-X)[49][50]

- Roscosmos Progress (multiple variants) (2000–present)[51][52]

- Energia Soyuz (multiple variants) (2001–present)[53][54]

- SpaceX Dragon 2 (2020–present)[55][56]

- Retired

- Automated Transfer Vehicle (ATV) (2008–2015)[57][58]

- H-II Transfer Vehicle (HTV) (2009–2020)[59][60]

- Space Shuttle (1998–2011)[61][62]

- SpaceX Dragon 1 (2012–2020)[63][64]

Tiangong space station

The Tiangong space station is supported by the following spacecraft:

Tiangong program

The Tiangong program relied on the following spacecraft.

- Shenzhou program (2011–2016)[69][70]

Mir

The Mir space station was in orbit from 1986 to 2001 and was supported and visited by the following spacecraft:

- Roscosmos Progress (multiple variants) (1986–2000)[71][72] – An additional Progress spacecraft was used in 2001 to deorbit Mir.[73][74]

- Energia Soyuz (multiple variants) (1986–2000)[42][75]

- Space Shuttle (1995–1998)[76][77]

Skylab

- Apollo command and service module (1973–1974)[78][79]

Salyut programme

- Energia Soyuz (multiple variants) (1971–1986)[75][80]

Docking and berthing

Maintenance

Research

Research conducted on the Mir included the first long term space based ESA research project EUROMIR 95 which lasted 179 days and included 35 scientific experiments.[81]

During the first 20 years of operation of the International Space Station, there were around 3,000 scientific experiments in the areas of biology and biotech, technology development, educational activities, human research, physical science, and Earth and space science.[82][83]

Materials research

Space stations provide a useful platform to test the performance, stability, and survivability of materials in space. This research follows on from previous experiments such as the Long Duration Exposure Facility, a free flying experimental platform which flew from April 1984 until January 1990.[84][85]

- Mir Environmental Effects Payload (1996–1997)[86][87]

- Materials International Space Station Experiment (2001–present)[88][89]

Human research

Botany

Space tourism

Finance

As it currently costs on average $10,000 to $25,000 per kilogram to launch anything into orbit, space stations remain the exclusive province of government space agencies, which are primarily funded by taxation. In the case of the International Space Station, space tourism makes up a small portion of money to run it.

Legacy

Technology spinoffs

International cooperation and economy

Cultural impact

Space settlement

See also

References

- ↑ Clark, Stephen. "Chinese astronaut launch breaks record for most people in orbit – Spaceflight Now". https://spaceflightnow.com/2023/05/30/chinese-astronaut-launch-breaks-record-for-most-people-in-orbit/.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Mann, Adam (January 25, 2012). "Strange Forgotten Space Station Concepts That Never Flew". Wired. https://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2012/01/space-station-concepts/.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "The First Space Station". Boys' Life: p. 20. September 1989. https://books.google.com/books?id=z2YEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA20.

- ↑ "Science: Sun Gun". Time. July 9, 1945. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,852344-1,00.html. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- ↑ "Project Olympus (1962)". WIRED. 2013-09-02. https://www.wired.com/2013/09/project-olympus-1962/. Retrieved 2023-10-12.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Ivanovich, Grujica S. (2008). Salyut – The First Space Station: Triumph and Tragedy. Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-73973-1. OCLC 304494949.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Chladek, Jay (2017). Outposts on the Frontier: A Fifty-Year History of Space Stations. Clayton C. Anderson. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-2292-2. OCLC 990337324.

- ↑ Portree, D. S. F. (1995). "Mir Hardware Heritage". NASA. http://ston.jsc.nasa.gov/collections/TRS/_techrep/RP1357.pdf.

- ↑ Hall, R., ed (2000). The History of Mir 1986–2000. British Interplanetary Society. ISBN 978-0-9506597-4-9. https://archive.org/details/historyofmir19860000unse.

- ↑ "History and Timeline of the ISS". https://www.iss-casis.org/about/iss-timeline/.

- ↑ "Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering". Usu.edu. http://www.usu.edu/mae/aerospace/publications/JDSC_RoadToAutonomy.pdf.

- ↑ Zak, Anatoly (22 May 2009). "Russia 'to save its ISS modules'". BBC News. https://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/8064060.stm.

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (25 September 2017). "International partners in no rush regarding future of ISS". http://spacenews.com/international-partners-in-no-rush-regarding-future-of-iss/.

- ↑ Kelly, Thomas (2000). Engineering Challenges to the Long-Term Operation of the International Space Station. National Academies Press. pp. 28–30. ISBN 978-0-309-06938-0. https://www.nap.edu/read/9794/chapter/8.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Foust, Jeff (18 December 2024). "Axiom Space revises space station assembly plans". SpaceNews. https://spacenews.com/axiom-space-revises-space-station-assembly-plans/.

- ↑ Barbosa, Rui (29 September 2011). "China launches TianGong-1 to mark next human space flight milestone". NASASpaceflight.com. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2011/09/china-major-human-space-flight-milestone-tiangong-1s-launch/.

- ↑ Staff (1 April 2018). "Tiangong-1: Defunct China space lab comes down over South Pacific". BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-43614408.

- ↑ Chang, Kenneth (1 April 2018). "China's Tiangong-1 Space Station Has Fallen Back to Earth Over the Pacific". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/01/science/chinese-space-station-crash-tiangong.html.

- ↑ Dickinson, David (10 November 2017). "China's Tiangong 1 Space Station to Burn Up". http://www.skyandtelescope.com/astronomy-news/chinas-tiangong-1-set-to-reenter-in-the-coming-months/.

- ↑ Liptak, Andrew (20 July 2019). "China has deorbited its experimental space station". The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2019/7/20/20701831/china-tiangong-2-deorbited-experimental-space-station.

- ↑ "China launches first module of new space station". BBC News. 29 April 2021. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-china-56924370.

- ↑ Wall, Mike (7 January 2021). "China plans to launch core module of space station this year" (in en). https://www.space.com/china-space-station-core-module-launch-spring-2021.

- ↑ Clark, Stephen. "China to begin construction of space station this year – Spaceflight Now" (in en-US). https://spaceflightnow.com/2021/01/10/china-to-begin-construction-of-space-station-this-year/.

- ↑ Dobrijevic, Daisy; Jones, Andrew (2021-08-24). "China's space station, Tiangong: A complete guide" (in en). https://www.space.com/tiangong-space-station.

- ↑ As, Ganesh (2020-03-13). "Mir, the first modular space station" (in en-IN). The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. https://www.thehindu.com/children/mir-the-first-modular-space-station/article31057476.ece.

- ↑ Williams, Matt; Today, Universe. "Looking back at the Mir space station" (in en). https://phys.org/news/2015-06-mir-space-station.html.

- ↑ "State space corporation ROSCOSMOS |". http://en.roscosmos.ru/202/.

- ↑ Gebhardt, Chris (2016-05-11). "CRS-8 Dragon completes ISS mission, splashes down in Pacific" (in en-US). https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2016/05/crs-8-dragon-iss-mission-splashdown-pacific/.

- ↑ Bergin, Chris (2016-04-16). "BEAM installed on ISS following CRS-8 Dragon handover" (in en-US). https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2016/04/beam-iss-installation-dragon-handover/.

- ↑ Davis, Jason (2016-04-05). "All about BEAM, the space station's new inflatable module" (in en). The Planetary Society. https://www.planetary.org/articles/20160405-beam-preview.

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (2022-01-21). "Bigelow Aerospace transfers BEAM space station module to NASA" (in en-US). https://spacenews.com/bigelow-aerospace-transfers-beam-space-station-module-to-nasa/.

- ↑ Chang, Kenneth (27 January 2014). "Beings Not Made for Space". New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/28/science/bodies-not-made-for-space.html.

- ↑ "Space Settlements: A Design Study". NASA. 1975. https://settlement.arc.nasa.gov/75SummerStudy/s.s.doc.html.

- ↑ Bell, Trudy E. (2007). "Preventing "Sick" Spaceships". https://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/2007/11may_locad3/.

- ↑ "Basics of Space Flight Section II. Space Flight Projects". https://www2.jpl.nasa.gov/basics/bsf11-3.php.

- ↑ Brown, Michael J. I. (5 December 2017). "Curious Kids: Where does the oxygen come from in the International Space Station, and why don't they run out of air?" (in en). http://theconversation.com/curious-kids-where-does-the-oxygen-come-from-in-the-international-space-station-and-why-dont-they-run-out-of-air-82910.

- ↑ Russian Space Stations (wikisource).

- ↑ "Are there military space stations out there?" (in en-us). 2008-06-23. https://science.howstuffworks.com/military-space-station.htm.

- ↑ Hitchens, Theresa (2019-07-02). "Pentagon Eyes Military Space Station" (in en-US). https://breakingdefense.com/2019/07/pentagon-eyes-military-space-station/.

- ↑ "Mission STS-127". Aug 13, 2008. https://www.asc-csa.gc.ca/eng/missions/sts-127.asp.

- ↑ Madrigal, Alexis. "March 22, 1995: Longest Human Space Adventure Ends" (in en-US). Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. https://www.wired.com/2010/03/0322cosmonaut-space-record/. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Zak, Anatoly. "The Strange Trip of Soyuz T-15" (in en). https://www.smithsonianmag.com/air-space-magazine/moving-day-orbit-strange-trip-soyuz-t-15-180959014/.

- ↑ "NASA Adds Sierra Nevada's Dream Chaser To ISS Supply Vehicles" (in en-US). 15 January 2016. https://techcrunch.com/2016/01/14/nasa-adds-sierra-nevadas-dream-chaser-to-iss-supply-vehicles/.

- ↑ "First Dream Chaser vehicle takes shape" (in en-US). 2022-04-29. https://spacenews.com/first-dream-chaser-vehicle-takes-shape/.

- ↑ "Russia's position in space race above India but below US and China" (in en). https://realnoevremya.com/articles/4793-russias-position-in-space-race-above-india-but-below-us-and-china.

- ↑ "Orel, the russian capsule that will replace the Soyuz" (in en-US). 2020-07-16. https://www.enkey.it/en/2020/07/16/orel-the-russian-capsule-that-will-replace-the-soyuz/.

- ↑ "Orbital's Antares launches Cygnus on debut mission to ISS" (in en-US). 2013-09-18. https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2013/09/orbitals-antares-loft-cygnus-debut-mission-iss/.

- ↑ "Cygnus sets date for next ISS mission – Castor XL ready for debut" (in en-US). 2014-10-08. https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2014/10/cygnus-next-iss-mission-castor-xl-debut/.

- ↑ Clark, Stephen. "Last in current line of Japan's HTV cargo ships departs space station – Spaceflight Now" (in en-US). https://spaceflightnow.com/2020/08/18/htv-9-iss-departure/.

- ↑ Noumi, Ai; Ujiie, Ryo; Ueda, Satoshi; Someya, Kazunori; Ishihama, Naoki; Kondoh, Yoshinori (2018-01-08). "Verification of HTV-X resilient design by simulation environment with model-based technology" (in en). 2018 AIAA Modeling and Simulation Technologies Conference. AIAA SciTech Forum (Kissimmee, Florida: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics). doi:10.2514/6.2018-1926. ISBN 978-1-62410-528-9. https://arc.aiaa.org/doi/10.2514/6.2018-1926.

- ↑ "Progress cargo ship". http://www.russianspaceweb.com/progress.html.

- ↑ "Progress MS – Spacecraft & Satellites" (in en-US). https://spaceflight101.com/spacecraft/progress-ms/.

- ↑ "Spaceflight mission report: Soyuz TM-32". http://www.spacefacts.de/mission/english/soyuz-tm32.htm.

- ↑ Bergin, Chris (2016-10-30). "Soyuz MS-01 trio return to Earth" (in en-US). https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2016/10/soyuz-ms-01-trio-trip-earth/.

- ↑ "SpaceX's debut Cargo Dragon 2 docks to Station" (in en-US). 2020-12-06. https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2020/12/spacex-next-gen-cargo-dragon-crs21/.

- ↑ Gebhardt, Chris (2021-01-11). "CRS-21 Dragon completes mission with splashdown off Tampa" (in en-US). https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2021/01/dragon-departs-iss-with-science/.

- ↑ Jenniskens, Peter; published, Jason Hatton (2008-09-25). "The Spectacular Breakup of ATV: One Final Experiment" (in en). https://www.space.com/5885-spectacular-breakup-atv-final-experiment.html.

- ↑ "Ariane 5 Launches Final ATV Mission to Station" (in en-US). 2014-07-30. https://spacenews.com/41433ariane-5-launches-final-atv-mission-to-station/.

- ↑ "Japan Launches Space Cargo Ship on Maiden Flight" (in en). 2009-09-10. https://www.space.com/7216-japan-launches-space-cargo-ship-maiden-flight.html.

- ↑ Graham, William (2020-05-25). "HTV-9 arrives at ISS on final mission" (in en-US). https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2020/05/h-iib-last-htv-mission-iss/.

- ↑ "Space History Photo: Madeleine Albright & Daniel Goldin at STS-88 Launch" (in en). 2012-05-22. https://www.space.com/15695-madeleine-albright-daniel-goldin-sts-88-launch.html.

- ↑ "The last voyage of NASA's space shuttle: Looking back at Atlantis' final mission 10 years later" (in en). 2021-07-09. https://www.space.com/space-shuttle-final-mission-atlantis-10-years.

- ↑ "SpaceX Launches Private Capsule on Historic Trip to Space Station" (in en). 2012-05-22. https://www.space.com/15805-spacex-private-capsule-launches-space-station.html.

- ↑ Clark, Stephen. "With successful splashdown, SpaceX retires first version of Dragon spacecraft – Spaceflight Now" (in en-US). https://spaceflightnow.com/2020/04/07/spacex-retires-first-version-of-dragon-spacecraft/.

- ↑ "China space station: Shenzhou-12 delivers first crew to Tianhe module" (in en-GB). BBC News. 2021-06-17. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-57504052.

- ↑ Davenport, Justin (2021-06-16). "Shenzhou-12 and three crew members successfully launch to new Chinese space station" (in en-US). https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2021/06/shenzhou-12-new-chinese-station/.

- ↑ "China launches new cargo ship to Tianhe space station module" (in en). 2021-05-29. https://www.space.com/china-tianzhou-2-cargo-mission-launch.

- ↑ Graham, William (2021-05-29). "China launches Tianzhou 2, first cargo mission to new space station" (in en-US). https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2021/05/tianzhou-2-launch/.

- ↑ "China's unmanned Shenzhou 8 capsule returns to Earth" (in en-GB). BBC News. 2011-11-17. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-15776662.

- ↑ "China launches Shenzhou-11 crewed spacecraft" (in en-US). 2016-10-17. https://spacenews.com/china-launches-shenzhou-11-crewed-spacecraft/.

- ↑ "NASA – NSSDCA – Spacecraft – Details". https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1986-023A.

- ↑ "NASA – NSSDCA – Spacecraft – Details". https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=2000-064A.

- ↑ "Spaceflight Now | Mir | Space tug poised for launch to Russia's Mir station". https://spaceflightnow.com/mir/010116progroll/.

- ↑ "Spaceflight Now | Mir | Deorbiting space tug arrives at Russia's Mir station". https://spaceflightnow.com/mir/010127dock/.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Zak, Anatoly (2016-02-19). "Why Mir Mattered More Than You Think" (in en-US). https://www.popularmechanics.com/space/a19517/mir-space-station-30th-anniversary/.

- ↑ "When Atlantis Met MIR 25 Years Since STS-71" (in en-US). 16 June 2020. https://www.ccssc.org/sts71/.

- ↑ "STS-91 Space Radiation Environment Measurement Program -TOP-". https://iss.jaxa.jp/shuttle/flight/sts91/index_e.html.

- ↑ Compton, W. D.; Benson, C. D. (January 1983). "SP-4208 LIVING AND WORKING IN SPACE: A HISTORY OF SKYLAB – Chapter 15". https://history.nasa.gov/SP-4208/ch15.htm.

- ↑ Compton, W. D.; Benson, C. D. (January 1983). "SP-4208 LIVING AND WORKING IN SPACE: A HISTORY OF SKYLAB – Chapter 17". https://history.nasa.gov/SP-4208/ch17.htm.

- ↑ "The USSR launches first space station crew". https://www.russianspaceweb.com/soyuz10.html.

- ↑ Reiter, T. (December 1996). "Utilisation of the MIR Space Station". in Guyenne, T. D.. Space Station Utilisation, Proceedings of the Symposium held 30 September – 2 October, 1996 in Darmstadt, Germany. 385. European Space Agency. Noordwijk, The Netherlands: European Space Agency Publications Division. pp. 19–27. ISBN 92-9092-223-0. OCLC 38174384. Bibcode: 1996ESASP.385.....G. https://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1996ESASP.385...19R. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- ↑ Witze, Alexandra (2020-11-03). "Astronauts have conducted nearly 3,000 science experiments aboard the ISS" (in en). Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-03085-8. PMID 33149317. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-03085-8.

- ↑ Guzman, Ana (2020-10-26). "20 Breakthroughs from 20 Years of Science aboard the ISS". http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/research/news/iss-20-years-20-breakthroughs.

- ↑ Kinard, W.; O'Neal, R.; Wilson, B.; Jones, J.; Levine, A.; Calloway, R. (October 1994). "Overview of the space environmental effects observed on the retrieved long duration exposure facility (LDEF)" (in en). Advances in Space Research 14 (10): 7–16. doi:10.1016/0273-1177(94)90444-8. PMID 11540010. Bibcode: 1994AdSpR..14j...7K. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0273117794904448.

- ↑ Zolensky, Michael (May 2021). "The Long Duration Exposure Facility—A forgotten bridge between Apollo and Stardust" (in en). Meteoritics & Planetary Science 56 (5): 900–910. doi:10.1111/maps.13656. ISSN 1086-9379. Bibcode: 2021M&PS...56..900Z. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/maps.13656.

- ↑ Harvey, Gale A; Humes, Donald H; Kinard, William H (March 2000). "Shuttle and MIR Special Environmental Effects and Hardware Cleanliness" (in en). High Performance Polymers 12 (1): 65–82. doi:10.1088/0954-0083/12/1/306. ISSN 0954-0083. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1088/0954-0083/12/1/306.

- ↑ Nicogossian, Arnauld E.; Roy, Stephanie (November 1998). "Transitioning from Spacelab to the International Space Station". in Wilson, A.. 2nd European Symposium on Utilisation of the International Space Station. 433. Noordwijk, Netherlands: ESA Publications Division, ESTEC. 1999. pp. 653–658. ESA SP-433. ISBN 92-9092-732-1. OCLC 41941169. Bibcode: 1999ESASP.433..653N. https://articles.adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1999ESASP.433..653N. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ↑ de Groh, Kim K.; Banks, Bruce A.; Dever, Joyce A.; Jaworske, Donald A.; Miller, Sharon K. R.; Sechkar, Edward A.; Panko, Scott R. (March 2008). "International Space Station Experiments (Misse 1–7)". International Symposium on SM/MPAC and SEED Experiments. Tsukuba, Japan: NASA (published August 2009). TM-2008-215482. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20090005995/downloads/20090005995.pdf.

- ↑ Center, NASA's Marshall Space Flight (15 September 2021). "Marshall contributes to key Space Station experiment" (in en). https://www.theredstonerocket.com/tech_today/article_3268170a-1636-11ec-80cf-b3599068766d.html.

Bibliography

- Chladek, Jay (2017). Outposts on the Frontier: A Fifty-Year History of Space Stations. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-2292-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=V60oDwAAQBAJ.

- Haeuplik-Meusburger: Architecture for Astronauts – An Activity based Approach. Springer Praxis Books, 2011, ISBN 978-3-7091-0666-2.

- Ivanovich, Grujica S. (July 7, 2008). Salyut: the first space station: triumph and tragedy. Praxis. p. 426. ISBN 978-0-387-73585-6. https://archive.org/details/salyutfirstspace00ivan_020.

- Neri Vela, Rodolfo (1990). Manned space stations" Their construction, operation and potential application. Paris: European Space Agency SP-1137. ISBN 978-92-9092-124-0.

External links

- Read Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding Space Stations

- ISS – on Russian News Agency TASS, Official Infographic (in English)

- The star named ISS – on Roscosmos TV (in Russian)

- "Giant Doughnut Purposed as Space Station", Popular Science, October 1951, pp. 120–121; article on the subject of space exploration and a space station orbiting earth

Further reading

- Baker, David (2015). International Space Station : 1998-2011 (all stages) : an insight into the history, development, collaboration, production and role of the permanently manned earth-orbiting complex. Sparkford, Yeovil, Somerset: Haynes Manual. ISBN 978-0-85733-839-6. OCLC 945783975.

|