Chemistry:Norepinephrine (medication)

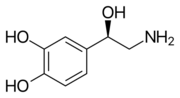

Skeletal formula of noradrenaline | |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Levarterenol, Levophed, Norepin, other |

| Other names | Noradrenaline (R)-(–)-Norepinephrine l-1-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-2-aminoethanol |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Physiology data | |

| Source tissues | Locus coeruleus; sympathetic nervous system; adrenal medulla |

| Target tissues | System-wide |

| Receptors | α1, α2, β1, β3 |

| Agonists | Sympathomimetic drugs, clonidine, isoprenaline |

| Antagonists | Tricyclic antidepressants, Beta blockers, antipsychotics |

| Metabolism | MAO-A; COMT |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | MAO-A; COMT |

| Excretion | Urine (84–96%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C8H11NO3 |

| Molar mass | 169.180 g·mol−1 |

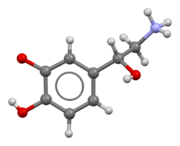

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.397±0.06 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 217 °C (423 °F) (decomposes) |

| Boiling point | 442.6 °C (828.7 °F) ±40.0°C |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Norepinephrine, also known as noradrenaline, is a medication used to treat people with very low blood pressure.[2] It is the typical medication used in sepsis if low blood pressure does not improve following intravenous fluids.[3] It is the same molecule as the hormone and neurotransmitter norepinephrine.[2] It is given by slow injection into a vein.[2]

Common side effects include headache, slow heart rate, and anxiety.[2] Other side effects include an irregular heartbeat.[2] If it leaks out of the vein at the site it is being given, norepinephrine can result in limb ischemia.[2] If leakage occurs the use of phentolamine in the area affected may improve outcomes.[2] Norepinephrine works by binding and activating alpha adrenergic receptors.[2]

Norepinephrine was discovered in 1946 and was approved for medical use in the United States in 1950.[2][4] It is available as a generic medication.[2]

Medical uses

Norepinephrine is used mainly as a sympathomimetic drug to treat people in vasodilatory shock states such as septic shock and neurogenic shock, while showing fewer adverse side-effects compared to dopamine treatment.[5][6]

Mechanism of action

It stimulates α1 and α2 adrenergic receptors to cause blood vessel contraction, thus increases peripheral vascular resistance and resulted in increased blood pressure. This effect also reduces the blood supply to gastrointestinal tract and kidneys. Norepinephrine acts on beta-1 adrenergic receptors, causing increase in heart rate and cardiac output.[7] However, the elevation in heart rate is only transient, as baroreceptor response to the rise in blood pressure as well as enhanced vagal tone ultimately result in a sustained decrease in heart rate.[8] Norepinephrine acts more on alpha receptors than the beta receptors.[9]

Names

Norepinephrine is the INN while noradrenaline is the BAN.

References

- ↑ "Structural studies of metabolic products of dopamine. IV. Crystal and molecular structure of (-)-noradrenaline". Acta Chemica Scandinavica. Series B 29 (8): 871–876. 1975. doi:10.3891/acta.chem.scand.29b-0871. PMID 1202890.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 "Norepinephrine Bitartrate". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. https://www.drugs.com/monograph/norepinephrine-bitartrate.html.

- ↑ (in en) Surgical Decision Making: Beyond the Evidence Based Surgery. Springer. 2016. p. 67. ISBN 9783319298245. https://books.google.com/books?id=2Z8YDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA67.

- ↑ (in en) Encyclopedia of the Neurological Sciences. Academic Press. 2014. p. 224. ISBN 9780123851581. https://books.google.com/books?id=hfjSVIWViRUC&pg=RA1-PA224.

- ↑ "Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016". Critical Care Medicine 45 (3): 486–552. March 2017. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000002255. PMID 28098591. https://archive.lstmed.ac.uk/19349/1/0.%20SSC%202020%20main%20paper%20ICM%20Revisions%20FINAL%20CLEAN%20copy.docx. "We recommend norepinephrine as the first-choice vasopressor (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence).".

- ↑ "Comparison of dopamine and norepinephrine in the treatment of shock". The New England Journal of Medicine 362 (9): 779–789. March 2010. doi:10.1056/nejmoa0907118. PMID 20200382.

- ↑ Pharmacology (3rd ed.). Springer Science and Business Media. 6 December 2012. p. 39. ISBN 9781468405248. https://books.google.com/books?id=r2ArBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA39. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- ↑ "Circulating Catecholamines". CV Physiology. 7 December 2022. https://cvphysiology.com/Blood%20Pressure/BP018.

- ↑ "Vasopressor and Inotropic Management Of Patients With Septic Shock". P & T 40 (7): 438–450. July 2015. PMID 26185405.

External links

- "Norepinephrine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://druginfo.nlm.nih.gov/drugportal/rn/51-41-2.

- "Norepinephrine bitartrate". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://druginfo.nlm.nih.gov/drugportal/rn/108341-18-0.

|