Biology:Selegiline

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /səˈlɛdʒɪliːn/ sə-LEJ-i-leen |

| Trade names | Eldepryl, Jumex, Zelapar, Emsam, others[1] |

| Other names | L-Deprenyl; (R)-(–)-N,α-Dimethyl-N-2-propynylphenethylamine; (R)-(–)-N-Methyl-N-2-propynylamphetamine; (R)-(–)-N-2-propynylmethamphetamine |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a697046 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, transdermal (patch) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 10% (oral), 73% (patch) |

| Protein binding | 94% |

| Metabolism | Intestines and liver |

| Metabolites | N-Desmethylselegiline, levoamphetamine, levomethamphetamine |

| Elimination half-life | 1.5–3.5 hours (oral),[2] 18–25 hours (transdermal)[3] |

| Excretion | Urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C13H17N |

| Molar mass | 187.286 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Selegiline, also known as L-deprenyl and sold under the brand names Eldepryl, Emsam, Selgin, among other names, is a medication which is used in the treatment of Parkinson's disease and major depressive disorder.[1] It is provided in the form of a capsule or tablet taken by mouth or orally disintegrating tablets taken on the tongue for Parkinson's disease and as a patch applied to skin for depression.

Selegiline acts as a monoamine oxidase inhibitor, and increases levels of monoamine neurotransmitters in the brain. At typical clinical doses used for Parkinson's disease, selegiline is a selective and irreversible inhibitor of monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B), increasing levels of dopamine in the brain. In larger doses (more than 20 mg/day), it loses its specificity for MAO-B and also inhibits MAO-A, which increases serotonin and norepinephrine levels in the brain.

Medical uses

Parkinson's disease

In its pill form, selegiline is used to treat symptoms of Parkinson's disease.[4] It is most often used as an adjunct to drugs such as levodopa (L-DOPA), although it has been used off-label as a monotherapy.[5][6] The rationale for adding selegiline to levodopa is to decrease the required dose of levodopa and thus reduce the motor complications of levodopa therapy.[7] Selegiline delays the point when levodopa treatment becomes necessary from about 11 months to about 18 months after diagnosis.[8] There is some evidence that selegiline acts as a neuroprotectant and reduces the rate of disease progression, though this is disputed.[6][7]

Selegiline has also been used off-label as a palliative treatment for dementia in Alzheimer's disease.[6]

Depression

Selegiline is also delivered via a transdermal patch used as a treatment for major depressive disorder.[9][10] Administration of transdermal selegiline bypasses hepatic first pass metabolism. This avoids inhibition of gastrointestinal and hepatic MAO-A activity, which would result in an increase of food-borne tyramine in the blood and possible related adverse effects, while allowing for a sufficient amount of selegiline to reach the brain for an antidepressant effect.[11]

A quantitative review published in 2015 found that for the pooled results of the pivotal trials, the number needed to treat (a sign of effect size, so a low number is better) for the patch for symptom reduction was 11, and for remission, was 9.[10] The number needed to harm (inverse of the NNT, a high number here is better) ranged from 387 for sexual side effects to 7 for application site reaction.[10] With regard to the likelihood to be helped or harmed (LHH), the analysis showed that the selegiline patch was 3.6 times as likely to lead to a remission vs. a discontinuation due to side effects; the LHH for remission vs. incidence of insomnia was 2.1; the LHH for remission vs. discontinuation due to insomnia was 32.7. The LHH for remission vs. insomnia and sexual dysfunction were both very low.[10]

Special populations

For all human uses and all forms, selegiline is pregnancy category C: studies in pregnant lab animals have shown adverse effects on the fetus but there are no adequate studies in humans.[4][9]

Side effects

Side effects of the tablet form in conjunction with levodopa include, in decreasing order of frequency, nausea, hallucinations, confusion, depression, loss of balance, insomnia, increased involuntary movements, agitation, slow or irregular heart rate, delusions, hypertension, new or increased angina pectoris, and syncope.[4] Most of the side effects are due to a high dopamine signaling, and can be alleviated by reducing the dose of levodopa.[1]

The main side effects of the patch form for depression include application-site reactions, insomnia, diarrhea, and sore throat.[9] The selegiline patch carries a black box warning about a possible increased risk of suicide, especially for young people,[9] as do all antidepressants since 2007.[12]

Interactions

Both the oral and patch forms come with strong warnings against combining selegiline with drugs that could produce serotonin syndrome, such as SSRIs and the cough medicine dextromethorphan.[4][9][13] Selegiline in combination with the opioid analgesic pethidine is not recommended, as it can lead to severe adverse effects.[13] Several other synthetic opioids such as tramadol and methadone, as well as various triptans, are contraindicated due to potential for serotonin syndrome.[14][15]

Birth control pills containing ethinylestradiol and a progestin increase the bioavailability of selegiline by 10- to 20-fold.[16] High levels can lead to loss of MAO-B selectivity, and selegiline may begin inhibiting MAO-A as well. This increases susceptibility to side effects of non-selective MAOIs, such as tyramine-induced hypertensive crisis and serotonin toxicity when combined with serotonergic medications.[16]

Both forms of the drug carry warnings about food restrictions to avoid hypertensive crisis that are associated with MAO inhibitors.[4][9] The patch form was created in part to overcome food restrictions; clinical trials showed that it was successful. Additionally, in post-marketing surveillance from April 2006 to October 2010, only 13 self-reports of possible hypertensive events or hypertension were made out of 29,141 exposures to the drug, and none were accompanied by objective clinical data.[10] The lowest dose of the patch method of delivery, 6 mg/24 hours, does not require any dietary restrictions.[17] Higher doses of the patch and oral formulations, whether in combination with the older non-selective MAOIs or in combination with the reversible MAO-A inhibitor moclobemide, require a low-tyramine diet.[13]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Selegiline is a selective inhibitor of MAO-B, irreversibly inhibiting it by binding to it covalently.[1][18] It is generally believed to exert its effects by blocking the breakdown of dopamine, thus increasing its activity;[19] however, recent evidence suggests that MAO-A is solely or almost entirely responsible for the metabolism of dopamine.[20] Its possible neuroprotective properties may be due to protecting nearby neurons from the free oxygen radicals that are released by MAO-B activity. At higher doses, selegiline loses its selectivity for MAO-B and inhibits MAO-A as well.[1]

Selegiline potentiates the release of catecholamines independent of its MAO-B inhibiting action. As such, it has been called the "first synthetic catecholaminergic activity enhancer substance".[21][22]

Selegiline also inhibits CYP2A6 and can increase the effects of nicotine as a result.[23] Selegiline also appears to activate σ1 receptors, having a relatively high affinity for these receptors of approximately 400 nM.[24][25]

Pharmacokinetics

Selegiline has an oral bioavailability of about 10%, which increases when ingested together with a fatty meal, as the molecule is fat soluble.[1][26] Selegiline and its metabolites bind extensively to plasma proteins (at a rate of 94%). They cross the blood–brain barrier and enter the brain, where they most concentrated at the thalamus, basal ganglia, midbrain, and cingulate gyrus.[6][9]

Selegiline is mostly metabolized in the intestines and liver; it and its metabolites are excreted in the urine.[1]

Buccal administration of selegiline results in 5-fold higher bioavailability, more reproducible blood concentration, and produces fewer amphetamine metabolites than the oral tablet form.[27]

Metabolism

Selegiline is metabolized by cytochrome P450 to L-desmethylselegiline and levomethamphetamine.[28][29] Desmethylselegiline has some activity against MAO-B, but much less than that of selegiline.[19][18] It is thought to be further metabolized by CYP2C19.[30] Levomethamphetamine (the less potent of the two enantiomers of methamphetamine) is converted to levoamphetamine (the less potent of the two enantiomers of amphetamine, with regards to psychological effects).

Due to the presence of these metabolites, people taking selegiline may test positive for "amphetamine" or "methamphetamine" on drug screening tests.[31] While the amphetamine metabolites may contribute to selegiline's ability to inhibit reuptake of the neurotransmitters dopamine and norepinephrine, they have also been associated with orthostatic hypotension and hallucinations.[29][32][33] The recovery of selegiline from urine is high at 87%, which has caused some researchers to question the clinical relevance of its amphetamine metabolites.[34] The amphetamine metabolites are hydroxylated and, in phase II, conjugated by glucuronyltransferase.

A newer anti-Parkinson MAO-B inhibitor, rasagiline, metabolizes into 1(R)-aminoindan, which has no amphetamine-like characteristics.[35]

Patch

Following application of the patch to humans, an average of 25% to 30% of the selegiline content is delivered systemically over 24 hours. Transdermal dosing results in significantly higher exposure to selegiline and lower exposure to all metabolites when compared to oral dosing; this is due to the extensive first-pass metabolism of the pill form and low first-pass metabolism of the patch form. The site of application is not a significant factor in how the drug is distributed. In humans, selegiline does not accumulate in the skin, nor is it metabolized there.[9]

Chemistry

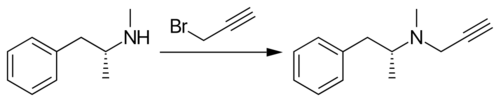

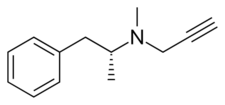

Selegiline belongs to the phenethylamine and amphetamine chemical families. It is also known as L-deprenyl, as well as (R)-(–)-N,α-dimethyl-N-(2-propynyl)phenethylamine or (R)-(–)-N-methyl-N-2-propynylamphetamine. The compound is a derivative of levomethamphetamine (L-methamphetamine) with a propargyl group attached to the nitrogen atom. This detail is borrowed from pargyline, an older MAO-B inhibitor of the phenylalkylamine group.[21] Selegiline is the levorotatory enantiomer of the racemic mixture deprenyl.

Selegiline is synthesized by the alkylation of (–)-methamphetamine using propargyl bromide.[36][37][38][39]

Another clinically used MAOI of the amphetamine class is tranylcypromine.

History

Following the discovery in 1952 that the tuberculosis drug iproniazid elevated the mood of people taking it, and the subsequent discovery that the effect was likely due to inhibition of MAO, many people and companies started trying to discover MAO inhibitors to use as antidepressants. Selegiline was discovered by Zoltan Ecseri at the Hungarian drug company, Chinoin (part of Sanofi since 1993),[40] which they called E-250.[41]:66–67 Chinoin received a patent on the drug in 1962 and the compound was first published in the scientific literature in English in 1965.[41]:67[42] Work on the biology and effects of E-250 in animals and humans was conducted by a group led by József Knoll at Semmelweis University which was also in Budapest.[41]:67

Deprenyl is a racemic compound (a mixture of two isomers called enantiomers). Further work determined that the levorotatory enantiomer was a more potent MAO-inhibitor, which was published in 1967, and subsequent work was done with the single enantiomer L-deprenyl.[41]:67[43][44]

In 1971, Knoll showed that selegiline selectively inhibits the B-isoform of monoamine oxidase (MAO-B) and proposed that it is unlikely to cause the infamous "cheese effect" (hypertensive crisis resulting from consuming foods containing tyramine) that occurs with non-selective MAO inhibitors. A few years later, two Parkinson's disease researchers based in Vienna, Peter Riederer and Walther Birkmayer, realized that selegiline could be useful in Parkinson's disease. One of their colleagues, Prof. Moussa B.H. Youdim, visited Knoll in Budapest and took selegiline from him to Vienna. In 1975, Birkmayer's group published the first paper on the effect of selegiline in Parkinson's disease.[44][45]

In the 1970s there was speculation that it could be useful as an anti-aging drug or aphrodisiac.[46]

In 1987 Somerset Pharmaceuticals in New Jersey, which had acquired the US rights to develop selegiline, filed a new drug application (NDA) with the FDA to market the drug for Parkinson's disease in the US.[47] While the NDA was under review, Somerset was acquired in a joint venture by two generic drug companies, Mylan and Bolan Pharmaceuticals.[47] Selegiline was approved for Parkinson's disease by the FDA in 1989.[47]

In the 1990s, J. Alexander Bodkin at McLean Hospital, an affiliate of Harvard Medical School, began a collaboration with Somerset to develop delivery of selegiline via a transdermal patch in order to avoid the well known dietary restrictions of MAO inhibitors.[46][48][49] Somerset obtained FDA approval to market the patch in 2006.[50]

As an anti-aging/longevity drug

Joseph Knoll and his team are credited with having developed selegiline. Although selegeline's development as a potential treatment for Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, and major depressive disorder was headed by other teams, Knoll remained at the forefront of research into the potential longevity enhancing effects of selegiline up until his death in 2018.[51][52][53] Knoll published How Selegiline ((-)-Deprenyl) Slows Brain Aging (2018) wherein he claims that:

"In humans, maintenance from sexual maturity on (-)-deprenyl (1mg daily) is, for the time being, the most promising prophylactic treatment to fight against the age related decay of behavioral performances, prolonging life, and preventing or delaying the onset of age-related neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's".[54]

The mechanism of selegiline's longevity-promoting effect has been researched by several groups, including Joseph Knoll and his associates at Semmelweis University, Budapest.[55] The drug has been determined to be a catecholaminergic activity enhancer when present in minuscule concentrations far below those at which monoamine oxidase inhibitory activity can be observed, thereby potentiating the release of catecholamine neurotransmitters in response to stimuli. Knoll maintains that micro-doses of selegiline act as a synthetic analogue to a known or unknown trace amine in order to preserve the brain catecholaminergic system, which he perceives as integral to the organism's ability to function in an adaptive, goal-directed and motivated manner during advancing physical age:

" ... enhancer regulation in the catecholaminergic brain stem neurons play[s] a key role in controlling the uphill period of life and the transition from adolescence to adulthood. The results of our longevity studies support the hypothesis that quality and duration of life rests upon the inborn efficiency of the catcholaminergic brain machinery, i.e. a high performing, long-living individual has a more active, more slowly deteriorating catecholaminergic system than its low performing, shorter living peer. Thus, a better brain engine allows for a better performance and a longer lifespan.

...

Since the catecholaminergic and serotonergic neurons in the brain stem are of key importance in ensuring that the mammalian organism works as a purposeful, motivated, goal-directed entity, it is hard to overestimate the significance of finding safe and efficient means to slow the decay of these systems with passing time. The conclusion that the maintenance on (-)-deprenyl that keeps the catecholaminergic neurnsn a higher activity level is a safe and efficient anti- aging therapy follows from the discovery of the enhancer regulation in the catecholaminergic neurons of the brain stem. From the finding that this regulation starts working on a high activity level after weaning and the enhanced activity subsists during the uphill period of life, until sexual hormones dampen the enhancer regulation in the catecholaminergic and serotonergic neurons in the brain stem, and this event signifies the transition from developmental longevity into postdevelopmental longevity, the downhill period of life."[54]

As a nootropic/"smart drug"

Selegiline is considered by some to be a nootropic,[56] both at clinical and sub-clinical dosages, and has been used off-label to improve cognitive performance. It has been shown to have protective activity against a range of neurotoxins and to increase the production of several brain growth factors, such as nerve growth factor, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, and glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor.[55] It has been demonstrated in numerous animal models to improve learning ability and preserve it during both ischemia and aging.[57][58][59][60]

Society and culture

In E for Ecstasy (a book examining the uses of the street drug ecstasy in the UK) the writer, activist and ecstasy advocate Nicholas Saunders highlighted test results showing that certain consignments of the drug also contained selegiline.[61] Consignments of ecstasy known as "Strawberry" contained what Saunders described as a "potentially dangerous combination of ketamine, ephedrine and selegiline," as did a consignment of "Sitting Duck" Ecstasy tablets.[62]

David Pearce wrote The Hedonistic Imperative[63] six weeks after starting taking selegiline.[64]

In Gregg Hurwitz's novel Out of the Dark,[65] selegiline (Emsam) and tyramine-containing food were used to assassinate the president of the United States.

Veterinary use

In veterinary medicine, selegiline is sold under the brand name Anipryl (manufactured by Zoetis). It is used in dogs to treat canine cognitive dysfunction and, at higher doses, pituitary-dependent hyperadrenocorticism (PDH).[66][67] Canine cognitive dysfunction is a form of dementia that mimics Alzheimer's disease in humans. Geriatric dogs treated with selegiline show improvements in sleeping pattern, reduced incontinence, and increased activity level; most show improvements by one month.[68][69] Though it is labeled for dog use only, selegiline has been used off-label for geriatric cats with cognitive dysfunction.[70]

Selegiline's efficacy in treating pituitary-dependent hyperadrenocorticism has been disputed.[66] Theoretically, it works by increasing dopamine levels, which downregulates the release of ACTH, eventually leading to reduced levels of cortisol.[70] Some claim that selegiline is only effective at treating PDH caused by lesions in the anterior pituitary (which comprise most canine cases).[71] The greatest sign of improvement is lessening of abdominal distention.[68]

Side effects in dogs are uncommon, but they include vomiting, diarrhea, diminished hearing, salivation, decreased weight and behavioral changes such as hyperactivity, listlessness, disorientation, and repetitive motions.[67][71]

Selegiline does not appear to have a clinical effect on horses.[71]

ADHD research

Selegiline has been limitedly studied in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in both children/adolescents and adults.[72][73] In a small randomized trial of selegiline for treatment of ADHD in children, there were improvements in attention, hyperactivity, and learning/memory performance but not in impulsivity.[74] A small clinical randomized trial compared selegiline to methylphenidate, a first line treatment for ADHD, and reported equivalent efficacy as assessed by parent and teacher ratings.[75] In another small randomized controlled trial of selegiline for the treatment of adult ADHD, a high dose of the medication for 6 weeks was not significantly more effective than placebo in improving symptoms.[73][76][77]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 "Selegiline". Drugs.com. https://www.drugs.com/international/selegiline.html.

- ↑ "Résumé des Caractéristiques du Produit". http://agence-prd.ansm.sante.fr/php/ecodex/rcp/R0209724.htm.

- ↑ https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2007/021336s002lbl.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Selegiline oral label. Updated December 31, 2008

- ↑ "Clinical applications of MAO-inhibitors". Current Medicinal Chemistry 11 (15): 2033–2043. August 2004. doi:10.2174/0929867043364775. PMID 15279566.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 "Selegiline Hydrochloride Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. https://www.drugs.com/monograph/selegiline-hydrochloride.html.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Monoamine oxidase type B inhibitors in early Parkinson's disease: meta-analysis of 17 randomised trials involving 3525 patients". BMJ 329 (7466): 593. September 2004. doi:10.1136/bmj.38184.606169.AE. PMID 15310558.

- ↑ "Selegiline's neuroprotective capacity revisited". Journal of Neural Transmission 110 (11): 1273–1278. November 2003. doi:10.1007/s00702-003-0083-x. PMID 14628191.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 Emsam label Last revised Sept 2014. Index page at FDA

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 "Placing transdermal selegiline for major depressive disorder into clinical context: number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed". Journal of Affective Disorders 151 (2): 409–417. November 2013. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.06.027. PMID 23890583.

- ↑ "Transdermal selegiline for the treatment of major depressive disorder". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 3 (5): 527–537. November 2007. PMID 19300583.

- ↑ "Expanding the black box - depression, antidepressants, and the risk of suicide". The New England Journal of Medicine 356 (23): 2343–2346. June 2007. doi:10.1056/NEJMp078015. PMID 17485726.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 "Safety of selegiline (deprenyl) in the treatment of Parkinson's disease". Drug Safety 19 (1): 11–22. July 1998. doi:10.2165/00002018-199819010-00002. PMID 9673855.

- ↑ "Drug interactions with selegiline versus rasagiline". Basal Ganglia. Monoamine oxidase B Inhibitors 2 (4, Supplement): S27–S31. December 1, 2012. doi:10.1016/j.baga.2012.06.003. ISSN 2210-5336.

- ↑ "Monoamine oxidase inhibitors, opioid analgesics and serotonin toxicity". British Journal of Anaesthesia 95 (4): 434–441. October 2005. doi:10.1093/bja/aei210. PMID 16051647.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Dose linearity study of selegiline pharmacokinetics after oral administration: evidence for strong drug interaction with female sex steroids". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 47 (3): 249–254. March 1999. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00891.x. PMID 10215747.

- ↑ "The selegiline transdermal system (emsam): a therapeutic option for the treatment of major depressive disorder". P & T 33 (4): 212–246. April 2008. PMID 19750165.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Parkinson's Disease: Diagnosis & Clinical Management (2nd ed.). Demos Medical Publishing. 2007. pp. 503, 505. ISBN 978-1-934559-87-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=zUp54Dm-Y7MC&pg=PA503.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (9th ed.). Lange Medical Books/McGraw Hill. 2004. pp. 453. ISBN 978-0-07-141092-2. https://archive.org/details/basicclinicalpha00katz_168.

- ↑ "Redefining differential roles of MAO-A in dopamine degradation and MAO-B in tonic GABA synthesis". Experimental & Molecular Medicine 53 (7): 1148–1158. July 2021. doi:10.1038/s12276-021-00646-3. PMID 34244591.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "The History of Selegiline/(-)-Deprenyl the First Selective Inhibitor of B-Type Monoamine Oxidase and The First Synthetic Catecholaminergic Activity Enhancer Substance" (in en). March 13, 2014. http://inhn.org/archives/miklya-collection/the-history-of-selegiline-deprenyl-the-first-selective-inhibitor-of-b-type-monoamine-oxidase-and-the-first-synthetic-catecholaminergic-activity-enhancer-substance.html.

- ↑ "[History of deprenyl--the first selective inhibitor of monoamine oxidase type B]". Voprosy Meditsinskoi Khimii 43 (6): 482–493. 1997. PMID 9503565.

- ↑ "Selegiline is a mechanism-based inactivator of CYP2A6 inhibiting nicotine metabolism in humans and mice". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 324 (3): 992–999. March 2008. doi:10.1124/jpet.107.133900. PMID 18065502.

- ↑ Sigma Receptors. Academic Press. 1994. pp. 84. ISBN 978-0-12-376350-1.

- ↑ Acetylcholine, Sigma Receptors, CCK and Eicosanoids, Neurotoxins. Taylor & Francis. 1993. pp. 124. ISBN 978-0-7484-0063-8.

- ↑ "Absorption and presystemic metabolism of selegiline hydrochloride at different regions in the gastrointestinal tract in healthy males". Pharmaceutical Research 13 (10): 1535–1540. October 1996. doi:10.1023/A:1016035730754. PMID 8899847.

- ↑ "A new formulation of selegiline: improved bioavailability and selectivity for MAO-B inhibition". Journal of Neural Transmission 110 (11): 1241–1255. November 2003. doi:10.1007/s00702-003-0036-4. PMID 14628189.

- ↑ "Deprenyl (selegiline), a selective MAO-B inhibitor with active metabolites; effects on locomotor activity, dopaminergic neurotransmission and firing rate of nigral dopamine neurons". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 259 (2): 841–847. November 1991. PMID 1658311.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2012. ISBN 978-1609133450.

- ↑ "Selegiline metabolism and cytochrome P450 enzymes: in vitro study in human liver microsomes". Pharmacology & Toxicology 86 (5): 215–221. May 2000. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0773.2000.pto860504.x. PMID 10862503.

- ↑ "Methamphetamine and amphetamine derived from the metabolism of selegiline". Journal of Forensic Sciences 40 (6): 1100–1102. November 1995. doi:10.1520/JFS13885J. PMID 8522918.

- ↑ "Contrasting neuroprotective and neurotoxic actions of respective metabolites of anti-Parkinson drugs rasagiline and selegiline". Neuroscience Letters 355 (3): 169–172. January 2004. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2003.10.067. PMID 14732458.

- ↑ "Are metabolites of l-deprenyl (Selegiline) useful or harmful? Indications from preclinical research". Deprenyl — Past and Future. 48. January 1, 1996. 61–73. doi:10.1007/978-3-7091-7494-4_6. ISBN 978-3-211-82891-5.

- ↑ "Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of selegiline". Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. Supplementum 126: 93–99. November 1989. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.1989.tb01788.x. PMID 2515726.

- ↑ "Clinical pharmacology of rasagiline: a novel, second-generation propargylamine for the treatment of Parkinson disease". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 45 (8): 878–894. August 2005. doi:10.1177/0091270005277935. PMID 16027398. http://jcp.sagepub.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16027398.

- ↑ Ecsery Z, Kosa I, Knoll J, Somfai E, "Verfahren zur Herstellung von neuen,optisch aktiven Phenylisopylamin-Derivaten [Process for the preparation of new, optically active phenylisopylamine derivatives]", DE patent 1568277, published 1970-04-30, assigned to Chinoin Gyógyszer-és Vegyészeti Termékek Gyára RT

- ↑ J. Hermann Nee Voeroes, Z. Ecsery, G. Sabo, L. Arvai, L. Nagi, O. Orban, E. Sanfai, U.S. Patent 4,564,706 (1986)

- ↑ Hájicek J, Hrbata J, Pihera P, Brunová B, Ferenc M, Krepelka J, Kvapil L, Pospisil J, "Method for the production of selegiline hydrochloride", EP patent 344675, published 989-12-06, assigned to SPOFA Spojené Podniky Pro Zdravotnickou Vyrobu

- ↑ "2-Methyl-3-butyn-2-ol as an acetylene precursor in the Mannich reaction. A new synthesis of suicide inactivators of monoamine oxidase". The Journal of Organic Chemistry 42 (15): 2637–2639. July 1977. doi:10.1021/jo00435a026. PMID 874623.

- ↑ "Sanofi Extends Holding in Chinoin". The Pharma Letter. September 19, 1993. https://www.thepharmaletter.com/article/sanofi-extends-holding-in-chinoin.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 "The pharmacology of selegiline". Monoamine Oxidases and Their Inhibitors. International Review of Neurobiology. 100. Academic Press. 2011. ISBN 978-0-12-386468-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=236nMbuZt2EC&pg=PA65.

- ↑ "Phenylisopropylmethylpropinylamine (E-250), a new spectrum psychic energizer". Archives Internationales de Pharmacodynamie et de Therapie 155 (1): 154–164. May 1965. PMID 4378644.

- ↑ "Comparative pharmacological analysis of the optical isomers of phenyl-isopropyl-methyl-propinylamine (E-250)". Acta Physiologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 32 (4): 377–387. 1967. PMID 5595908.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 "The psychopharmacology of life and death. Interview with Joseph Knoll.". The Psychopharmacologists, Vol. III: Interviews. London: Arnold. 2000. pp. 81–110. ISBN 978-0-340-76110-6.

- ↑ "The potentiation of the anti akinetic effect after L-dopa treatment by an inhibitor of MAO-B, Deprenil". Journal of Neural Transmission 36 (3–4): 303–326. 1975. doi:10.1007/BF01253131. PMID 1172524. http://link.springer.de/link/service/journals/00702/bibs/5036003/50360303.htm.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 "Bodkin is Patching up Depression". Harvard University Gazette. November 7, 2002. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2002/11/bodkin-is-patching-up-depression/.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Mylan: 50 Years of Unconventional Success: Making Quality Medicine Affordable and Accessible. University Press of New England. 2011. pp. 50. ISBN 978-1-61168-269-4.

- ↑ "Selegiline transdermal system: in the treatment of major depressive disorder". Drugs 67 (2): 257–65; discussion 266–7. 2007. doi:10.2165/00003495-200767020-00006. PMID 17284087.

- ↑ "Patch Raises New Hope For Beating Depression". The New York Times. 3 December 2002. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/2002/12/03/health/patch-raises-new-hope-for-beating-depression.html.

- ↑ "Emsam: the first year". Psychiatry 4 (6): 19–21. June 2007. PMID 20711332.

- ↑ "Geroprotection in the future. In memoriam of Joseph Knoll: The selegiline story continues". European Journal of Pharmacology 868: 172793. February 2020. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.172793. PMID 31743738. http://repo.lib.semmelweis.hu//handle/123456789/8055.

- ↑ "Longevity study with low doses of selegiline/(-)-deprenyl and (2R)-1-(1-benzofuran-2-yl)-N-propylpentane-2-amine (BPAP)". Life Sciences 167: 32–38. December 2016. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2016.10.023. PMID 27777099.

- ↑ "In memoriam Joseph Knoll (1925-2018) | Hungarian Society for Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology". https://huphar.org/en/in-memoriam-joseph-knoll-1925-2018/.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 How Selegiline ((-)-Deprenyl) Slows Brain Aging. Bentham Books. January 31, 2018. pp. (back of book). ISBN 978-1608055944.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 "The significance of selegiline/(-)-deprenyl after 50 years in research and therapy (1965-2015)". Molecular Psychiatry 21 (11): 1499–1503. November 2016. doi:10.1038/mp.2016.127. PMID 27480491.

- ↑ "Selegiline: Benefits, Dosing, Where To Buy, And More!" (in en-US). 2023-02-01. https://holisticnootropics.com/selegiline/.

- ↑ "The effects of rivastigmine plus selegiline on brain acetylcholinesterase, (Na, K)-, Mg-ATPase activities, antioxidant status, and learning performance of aged rats". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 4 (4): 687–699. August 2008. doi:10.2147/ndt.s3272. PMID 19043511.

- ↑ "Age-related memory decline and longevity under treatment with selegiline". Life Sciences 55 (25–26): 2155–2163. 1994. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(94)00396-3. PMID 7997074.

- ↑ "Selegiline combined with enriched-environment housing attenuates spatial learning deficits following focal cerebral ischemia in rats". Experimental Neurology 167 (2): 348–355. February 2001. doi:10.1006/exnr.2000.7563. PMID 11161623.

- ↑ "The pharmacological profile of (-)deprenyl (selegiline) and its relevance for humans: a personal view". Pharmacology & Toxicology 70 (5 Pt 1): 317–321. May 1992. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1992.tb00480.x. PMID 1608919.

- ↑ E for Ecstasy. London: N. Saunders. 1993. ISBN 978-0-9501628-8-1. OCLC 29388575.[page needed]

- ↑ "Test results of 30 samples of Ecstasy bought in British clubs between 11/94 and 7/95". http://ecstasy.org/testing/pillstilJuly.html.

- ↑ The Hedonistic Imperative. 1995. OCLC 44325836. https://www.hedweb.com/hedab.htm.

- ↑ "Sam Barker and David Pearce on Art, Paradise Engineering, and Existential Hope (With Guest Mix) | The FLI Podcast". 2020-06-24. https://futureoflife.org/2020/06/24/sam-barker-and-david-pearce-on-art-paradise-engineering-and-existential-hope-featuring-a-guest-mix/.

- ↑ Out of the dark. Penguin Books. 2019. p. 431. ISBN 9780718185480.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 "Selegiline Treatment of Canine Pituitary-Dependent Hyperadrenocorticism". Australian Veterinary Journal. 2004. http://www.lloydinc.com/pdfs/Endocrinology/Vol14_issue3_2004.pdf. (PDF)

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Essential Drug Data for Rational Therapy in Veterinary Practice. AuthorHouse. 2014. pp. 127–128. ISBN 978-1-4918-0010-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=CtfIAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA127.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 "Anipryl Tablets for Animal Use". Drugs.com. https://www.drugs.com/vet/anipryl-tablets.html.

- ↑ "Canine Cognitive Dysfunction". Veterinary Partner. http://www.veterinarypartner.com/Content.plx?P=A&A=2549.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. John Wiley & Sons. 2013. pp. 530. ISBN 978-1-118-68590-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=xAPa4WDzAnQC&pg=PA530.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 71.2 Saunders Handbook of Veterinary Drugs: Small and Large Animal. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2015. p. 722. ISBN 978-0-323-24485-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=ip8_CwAAQBAJ&pg=PA722.

- ↑ "Efficacy and safety of drugs for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: a network meta-analysis". European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 27 (10): 1335–1345. October 2018. doi:10.1007/s00787-018-1125-0. PMID 29460165.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 "Alternative pharmacological strategies for adult ADHD treatment: a systematic review". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics 16 (2): 131–144. 2016. doi:10.1586/14737175.2016.1135735. PMID 26693882.

- ↑ "Placebo-controlled study examining effects of selegiline in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 16 (4): 404–415. August 2006. doi:10.1089/cap.2006.16.404. PMID 16958566.

- ↑ "Selegiline in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children: a double blind and randomized trial". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry 27 (5): 841–845. August 2003. doi:10.1016/S0278-5846(03)00117-9. PMID 12921918.

- ↑ "A review of the pharmacotherapy of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Journal of Attention Disorders 5 (4): 189–202. March 2002. doi:10.1177/108705470100500401. PMID 11967475.

- ↑ "Pharmacotherapy of adult attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: review of evidence-based practices and future directions". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 9 (8): 1299–1310. June 2008. doi:10.1517/14656566.9.8.1299. PMID 18473705.

|