Chemistry:Sertraline

Sertraline, sold under the brand name Zoloft among others, is an antidepressant medication of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class[1] used to treat major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), panic disorder, and premenstrual dysphoric disorder.[2] Although also having approval for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), findings indicate it leads to only modest improvements in symptoms associated with this condition.[3][4]

The drug shares the common side effects and contraindications of other SSRIs, with high rates of nausea, diarrhea, headache, insomnia, mild sedation, dry mouth, and sexual dysfunction, but it appears not to lead to much weight gain, and its effects on cognitive performance are mild. Similar to other antidepressants, the use of sertraline for depression may be associated with a mildly elevated rate of suicidal thoughts in people under the age of 25 years old. It should not be used together with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs): this combination may cause serotonin syndrome, which can be life-threatening in some cases. Sertraline taken during pregnancy is associated with an increase in congenital heart defects in newborns.[5][6]

Sertraline was developed by scientists at Pfizer and approved for medical use in the United States in 1991. It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines[7] and available as a generic medication.[1] In 2016, sertraline was the most commonly prescribed psychotropic medication in the United States.[8] It was also the eleventh most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 42 million prescriptions in 2023,[9][10] and sertraline ranks among the top 10 most prescribed medications in Australia between 2017 and 2023.[11]

Sertraline's effectiveness is similar to that of other antidepressants in its class, such as fluoxetine and paroxetine, which are also considered first-line treatments and are better tolerated than the older tricyclic antidepressants.

Medical uses

Sertraline has been approved for major depressive disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), premenstrual dysphoric disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder (SAD), and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). Sertraline is approved for use in children with OCD.[12]

Depression

In meta-analyses, sertraline efficacy is similar to that of other SSRI antidepressants, with an odds ratio for response in clinical depression of between 1.44 and 1.67.[13][14] However, as with other antidepressants, the nature and clinical significance of this effect remain disputed.[15][16] A major study of sertraline in a broad primary care population found improvements in general mental health, quality of life, and anxiety.[17] However, it failed to find significant effects on depression in either the mildly or severely depressed, and the clinical relevance and accuracy of the positive effects found have been questioned.[18][19]

In several double-blind studies, sertraline was consistently more effective than placebo for dysthymia, a more chronic variety of depression, and comparable to imipramine in that respect. Sertraline also improves the functional impairments of dysthymia to a similar degree whether group Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy is undergone or not.[20]

Limited pediatric data also demonstrates a reduction in depressive symptoms in the pediatric population though remains a second-line therapy after fluoxetine.[21][22]

Comparison with other antidepressants

In general, sertraline efficacy is similar to that of other antidepressants.[23] For example, a meta-analysis of 12 new-generation antidepressants showed that sertraline and escitalopram are the best in terms of efficacy and acceptability in the acute-phase treatment of adults with depression.[24] Comparative clinical trials demonstrated that sertraline is similar in efficacy against depression to moclobemide,[25] nefazodone,[26] escitalopram, bupropion,[27] citalopram, fluvoxamine, paroxetine,[24] venlafaxine,[28] and mirtazapine.[29] Sertraline may be more efficacious for the treatment of depression in the acute phase (first four weeks) than fluoxetine.[30]

There are differences between sertraline and some other antidepressants in their efficacy in the treatment of different subtypes of depression and in their adverse effects. For severe depression, sertraline is as good as clomipramine but is better tolerated.[28] Sertraline appears to work better in melancholic depression than fluoxetine, paroxetine, and mianserin and is similar to the tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline and clomipramine.[23] In the treatment of depression accompanied by OCD, sertraline performs significantly better than desipramine on the measures of both OCD and depression.[20][31] Sertraline is equivalent to imipramine for the treatment of depression with co-morbid panic disorder, but it is better tolerated.[32] Compared with amitriptyline, sertraline offered a greater overall improvement in quality of life of depressed patients.[23]

Depression in elderly

Sertraline used for the treatment of depression in elderly (older than 60) patients is superior to placebo and comparable to another SSRI fluoxetine, and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) amitriptyline, nortriptyline and imipramine. Sertraline has much lower rates of adverse effects than these TCAs, with the exception of nausea, which occurs more frequently with sertraline. In addition, sertraline appears to be more effective than fluoxetine or nortriptyline in the older-than-70 subgroup.[33] Accordingly, a meta-analysis of antidepressants in older adults found that sertraline, paroxetine and duloxetine were better than placebo.[34] However, in a 2003 trial the effect size was modest, and there was no improvement in quality of life as compared to placebo.[35] With depression in dementia, there is no benefit of sertraline treatment compared to either placebo or mirtazapine.[36]

Obsessive–compulsive disorder

Sertraline is effective for the treatment of OCD in adults,[12] adolescents and children.[37][38][39] It was better tolerated and, based on intention-to-treat analysis, performed better than the gold standard of OCD treatment clomipramine.[40] Continuing sertraline treatment helps prevent relapses of OCD with long-term data supporting its use for up to 24 months.[41] The sertraline dosages necessary for the effective treatment of OCD are higher than the usual dosage for depression.[42] The onset of action is also slower for OCD than for depression. The treatment recommendation is to start treatment with half of the maximal recommended dose for at least two months. After that, the dose can be raised to the maximal recommended in the cases of unsatisfactory response.[43]

Cognitive behavioral therapy alone is not more effective than sertraline in adolescents and children; however, a combination of these treatments is effective.[39]

Panic disorder

Sertraline is superior to placebo for the treatment of panic disorder.[12] The response rate was independent of the dose. In addition to decreasing the frequency of panic attacks by about 80% (vs. 45% for placebo) and decreasing general anxiety, sertraline resulted in an improvement in quality of life on most parameters. The patients rated as "improved" on sertraline reported better quality of life than the ones who "improved" on placebo. The authors of the study argued that the improvement achieved with sertraline is different and of a better quality than the improvement achieved with a placebo.[44][45] Sertraline is equally effective for men and women,[45] and for patients with or without agoraphobia.[46] Previous unsuccessful treatment with benzodiazepines does not diminish its efficacy.[47] However, the response rate was lower for the patients with more severe panic.[46] Starting treatment simultaneously with sertraline and clonazepam, with subsequent gradual discontinuation of clonazepam, may accelerate the response.[48]

Double-blind comparative studies found sertraline to have the same effect on panic disorder as paroxetine or imipramine.[49] While imprecise, comparison of the results of trials of sertraline with separate trials of other anti-panic agents (clomipramine, imipramine, clonazepam, alprazolam, and fluvoxamine) indicates approximate equivalence of these medications.[44]

Other anxiety disorders

Sertraline has been successfully used for the treatment of social anxiety disorder.[50][51] All three major domains of the disorder (fear, avoidance, and physiological symptoms) respond to sertraline.[20] Maintenance treatment, after the response is achieved, prevents the return of the symptoms.[52] The improvement is greater among the patients with later, adult onset of the disorder.[53] In a comparison trial, sertraline was superior to exposure therapy, but patients treated with the psychological intervention continued to improve during a year-long follow-up, while those treated with sertraline deteriorated after treatment termination.[54] The combination of sertraline and cognitive behavioral therapy appears to be more effective in children and young people than either treatment alone.[55]

Sertraline has not been approved for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder; however, several guidelines recommend it as a first-line medication referring to good quality controlled clinical trials.[56][32][41]

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder

Sertraline is effective in alleviating the symptoms of premenstrual dysphoric disorder, a severe form of premenstrual syndrome.[57] Significant improvement was observed in 50–60% of cases treated with sertraline vs. 20–30% of cases on placebo. The improvement began during the first week of treatment, and in addition to mood, irritability, and anxiety, improvement was reflected in better family functioning, social activity, and general quality of life. Work functioning and physical symptoms, such as swelling, bloating, and breast tenderness, were less responsive to sertraline.[58][59] Taking sertraline only during the luteal phase, that is, the 12–14 days before menses is not as effective as continuous treatment.[57] Continuous treatment with sub-therapeutic doses of sertraline (25 mg vs. usual 50–100 mg) is also effective.[60]

Other indications

Sertraline is approved for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[12] The National Institute for Clinical Excellence recommends it for patients who prefer drug treatment to a psychological one.[61] Other guidelines also suggest sertraline as a first-line option for pharmacological therapy.[62][32] When necessary, long-term pharmacotherapy can be beneficial.[62] There are both negative and positive clinical trial results for sertraline, which may be explained by the types of psychological traumas, symptoms, and comorbidities included in the various studies.[41] Positive results were obtained in trials that included predominantly women (75%) with a majority (60%) having physical or sexual assault as the traumatic event.[62] Somewhat contrary to the above suggestions, a meta-analysis of sertraline clinical trials for PTSD found it to be statistically superior to placebo in the reduction of PTSD symptoms but the effect size was small.[3] Another meta-analysis relegated sertraline to the second line, proposing trauma focused psychotherapy as a first-line intervention. The authors noted that Pfizer had declined to submit the results of a negative trial for inclusion in the meta-analysis making the results unreliable.[4]

Sertraline, when taken daily, can be useful for the treatment of premature ejaculation.[63] A disadvantage of sertraline is that it requires continuous daily treatment to delay ejaculation significantly.[64]

A 2019 systematic review suggested that sertraline may be a good way to control anger, irritability, and hostility in depressed patients and patients with other comorbidities.[65]

Contraindications

Sertraline is contraindicated in individuals taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors or the antipsychotic pimozide. Sertraline concentrate contains ethanol and is therefore contraindicated with disulfiram. The prescribing information recommends that treatment of the elderly and patients with liver impairment "must be approached with caution". Due to the slower elimination of sertraline in these groups, their exposure to sertraline may be as high as three times the average exposure for the same dose.[12]

Side effects

Nausea, ejaculation failure, insomnia, diarrhea, dry mouth, somnolence, dizziness, tremor, headache, excessive sweating, fatigue, restless legs syndrome and decreased libido are the common adverse effects associated with sertraline with the greatest difference from placebo. Those that most often result in interruption of the treatment are nausea, diarrhea, and insomnia.[12] The incidence of diarrhea is higher with sertraline – especially when prescribed at higher doses – in comparison with other SSRIs.[66]

Over more than six months of sertraline therapy for depression, people showed no significant weight increase.[67] A 30-month-long treatment with sertraline for OCD also resulted in no significant weight gain.[68] Although the difference did not reach statistical significance, the average weight gain was lower for fluoxetine (1%) but higher for citalopram, fluvoxamine and paroxetine (2.5%). Of the sertraline group, 4.5% gained a large amount of weight (defined as more than 7% gain). This result compares favorably with placebo, where, according to the literature, 3–6% of patients gained more than 7% of their initial weight. The large weight gain was observed only among female members of the sertraline group; the significance of this finding is unclear because of the small size of the group.[68]

Over a two-week treatment of healthy volunteers, sertraline slightly improved verbal fluency but did not affect word learning, short-term memory, vigilance, flicker fusion time, choice reaction time, memory span, or psychomotor coordination.[69][70] In spite of lower subjective rating, that is, feeling that they performed worse, no clinically relevant differences were observed in the objective cognitive performance in a group of people treated for depression with sertraline for 1.5 years as compared to healthy controls.[71] In children and adolescents taking sertraline for six weeks for anxiety disorders, 18 out of 20 measures of memory, attention, and alertness stayed unchanged. Divided attention was improved and verbal memory under interference conditions decreased marginally. Because of the large number of measures taken, it is possible that these changes were still due to chance.[72] The unique effect of sertraline on dopaminergic neurotransmission may be related to these effects on cognition and vigilance.[73][74]

Sertraline has a low level of exposure of an infant through the breast milk and is recommended as the preferred option for the antidepressant therapy of breast-feeding mothers.[75][76] However, there is 29–42% increase in congenital heart defects among children whose mothers were prescribed sertraline during pregnancy,[5][6] with sertraline use in the first trimester associated with 2.7-fold increase in septal heart defects.[5]

Abrupt interruption of sertraline treatment may result in withdrawal or discontinuation syndrome. Dizziness, insomnia, anxiety, agitation, and irritability are common symptoms.[77] It typically occurs within a few days from drug discontinuation and lasts a few weeks.[78] The withdrawal symptoms for sertraline are less severe and frequent than for paroxetine, and more frequent than for fluoxetine.[77][78] In most cases symptoms are mild, short-lived, and resolve without treatment. More severe cases are often successfully treated by temporary reintroduction of the drug with a slower tapering-off rate.[79]

Sertraline and SSRI antidepressants in general may be associated with bruxism and other movement disorders.[80][81] Sertraline appears to be associated with microscopic colitis, a rare condition of unknown etiology.[82]

Sexual

Like other SSRIs, sertraline is associated with sexual side effects, including sexual arousal disorder, erectile dysfunction and difficulty achieving orgasm. While nefazodone and bupropion do not have negative effects on sexual functioning, 67% of men on sertraline experienced ejaculation difficulties versus 18% before the treatment.[83] Sexual arousal disorder, defined as "inadequate lubrication and swelling for women and erectile difficulties for men", occurred in 12% of people on sertraline as compared with 1% of patients on placebo. The mood improvement resulting from the treatment with sertraline sometimes counteracted these side effects, so that sexual desire and overall satisfaction with sex stayed the same as before the sertraline treatment. However, under the action of placebo the desire and satisfaction slightly improved.[84] Some people continue experiencing sexual side effects after they stop taking SSRIs.[85]

Suicide

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires all antidepressants, including sertraline, to carry a boxed warning stating that antidepressants increase the risk of suicide in persons younger than 25 years.[86][87][88] This warning is based on statistical analyses conducted by two independent groups of FDA experts that found a 100% increase of suicidal thoughts and behavior in children and adolescents, and a 50% increase in the 18–24 age group.[89][90][91]

Suicidal ideation and behavior in clinical trials are rare. For the above analysis, the FDA combined the results of 295 trials of 11 antidepressants for psychiatric indications to obtain statistically significant results. Considered separately, sertraline use in adults decreased the odds of suicidal behavior with a marginal statistical significance of 37%[91] or 50%[90] depending on the statistical technique used. The authors of the FDA analysis note that "given the large number of comparisons made in this review, chance is a very plausible explanation for this difference".[90] The more complete data submitted later by the sertraline manufacturer Pfizer indicated increased suicidal behavior.[92] Similarly, the analysis conducted by the UK MHRA found a 50% increase of odds of suicide-related events, not reaching statistical significance, in the patients on sertraline as compared to the ones on placebo.[93][94]

Therapeutic dosage

The therapeutic dosage varies according to the patient's age and/or clinical condition, but for all treatments with sertraline, it is recommended to start with lower dosages (25 to 50 mg/daily) and adjust according to the patient's therapeutic response, with a maximum maintenance dose of up to 200 mg per day.[95]

Overdose

Acute overdosage is often manifested by emesis, lethargy, ataxia, tachycardia and seizures. Plasma, serum or blood concentrations of sertraline and norsertraline, its major active metabolite, may be measured to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients or to aid in the medicolegal investigation of fatalities.[96] As with most other SSRIs its toxicity in overdose is considered relatively low.[97][98]

Interactions

As with other SSRIs, sertraline may increase the risk of bleeding with NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen, mefenamic acid), antiplatelet drugs, anticoagulants, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin E, and garlic supplements due to sertraline's inhibitory effects on platelet aggregation via blocking serotonin transporters on platelets.[99] Sertraline, in particular, may potentially diminish the efficacy of levothyroxine.[100]

Sertraline is a moderate inhibitor of CYP2D6 and CYP2B6 in vitro.[101] Accordingly, in human trials it caused increased blood levels of CYP2D6 substrates such as metoprolol, dextromethorphan, desipramine, imipramine and nortriptyline, as well as the CYP3A4/CYP2D6 substrate haloperidol.[102][103][104] This effect is dose-dependent; for example, co-administration with 50 mg of sertraline resulted in 20% greater exposure to desipramine, while 150 mg of sertraline led to a 70% increase.[105][106] In a placebo-controlled study, the concomitant administration of sertraline and methadone caused a 40% increase in blood levels of the latter, which is primarily metabolized by CYP2B6.[107] Bupropion is metabolized by CYP2B6, which is inhibited by sertraline, and this may result in an interaction between sertraline and bupropion.[108][109][110]

Sertraline had a slight inhibitory effect on the metabolism of diazepam, tolbutamide, and warfarin, which are CYP2C9 or CYP2C19 substrates; the clinical relevance of this effect was unclear.[105] As expected from in vitro data, sertraline did not alter the human metabolism of the CYP3A4 substrates erythromycin, alprazolam, carbamazepine, clonazepam, and terfenadine; neither did it affect metabolism of the CYP1A2 substrate clozapine.[105][12][111][101]

Sertraline did not affect the actions of digoxin and atenolol, which are not metabolized in the liver.[112] Case reports suggest that taking sertraline with phenytoin or zolpidem may induce sertraline metabolism and decrease its efficacy,[113][114] and that taking sertraline with lamotrigine may increase the blood level of lamotrigine, possibly by inhibition of glucuronidation.[115]

CYP2C19 inhibitor esomeprazole increased sertraline concentrations in blood plasma by approximately 40%.[116]

Clinical reports indicate that interaction between sertraline and the MAOIs isocarboxazid and tranylcypromine may cause serotonin syndrome. In a placebo-controlled study in which sertraline was co-administered with lithium, 35% of the subjects experienced tremors, while none of those taking placebo did.[105]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | Ki (nM) | Species | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NET | 420–925 | Human | [117][118][119] | |

| DAT | 22–315 | Human | [117][118][119] | |

| 5-HT1A | 35000+ | Human | [120] | |

| 5-HT2A | 2207 | Rat | [119] | |

| 5-HT2C | 2298 | Pig | [119] | |

| α1A | 1900 | Human | [121] | |

| α1B | 3500 | Human | [121] | |

| α1D | 2500 | Human | [121] | |

| α2 | 477–4100 | Human | [118][120] | |

| D2 | 10700 | Human | [120] | |

| H1 | 24000 | Human | [120] | |

| σ1 | 32–57 | Rat | [122][123] | |

| σ2 | 5297 | Rat | [123] | |

| Values are Ki (nM), unless otherwise noted. The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to or inhibits the site. | ||||

Sertraline is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). By binding to the serotonin transporter (SERT) it inhibits neuronal reuptake of serotonin and potentiates serotonergic activity in the central nervous system.[12] Over time, this leads to a downregulation of pre-synaptic 5-HT1A receptors, which is associated with an improvement in passive stress tolerance, and delayed downstream increase in expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which may contribute to a reduction in negative affective biases.[124][125] It does not significantly affect histamine, acetylcholine, GABA or benzodiazepine receptors.[12]

Sertraline also shows relatively high activity as an inhibitor of the dopamine transporter (DAT) occupying ~20% of DAT receptors at doses 200mg and above,[117][126][127] and antagonist of the sigma σ1 receptor (but not the σ2 receptor).[122][123][128] However, sertraline affinity for its main target (SERT) is much greater than its affinity for σ1 receptor and DAT.[129][117][123][122] Although there could be a role for the σ1 receptor in the pharmacology of sertraline, the significance of this receptor in its actions is unclear.[23] Similarly, the clinical relevance of sertraline's blockade of the dopamine transporter is uncertain.[117]

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Following a single oral dose of sertraline, mean peak blood levels of sertraline occur between 4.5 and 8.4 hours.[112] Bioavailability is likely linear and dose-proportional over a dose range of 150 to 200 mg.[112] Concomitant intake of sertraline with food slightly increases sertraline peak levels and total exposure.[112] There is an approximate 2-fold accumulation of sertraline with continuous administration and steady-state levels are reached within one week.[112]

Distribution

Sertraline is highly plasma protein bound (98.5%) across a concentration range of 20 to 500 ng/mL.[112] Despite the high plasma protein binding, sertraline and its metabolite desmethylsertraline at respective tested concentrations of 300 ng/mL and 200 ng/mL were found not to interfere with the plasma protein binding of warfarin and propranolol, two other highly plasma protein-bound drugs.[112]

Metabolism

Sertraline is subject to extensive first-pass metabolism, as indicated by a small study of radiolabeled sertraline in which less than 5% of plasma radioactivity was unchanged sertraline in two males.[112] The principal metabolic pathway for sertraline is N-demethylation into desmethylsertraline (N-desmethylsertraline) mainly by CYP2B6.[112][130] Reduction, hydroxylation, and glucuronide conjugation of both sertraline and desmethylsertraline also occur.[112] Desmethylsertraline, while pharmacologically active, is substantially (50-fold) weaker than sertraline as a serotonin reuptake inhibitor and its influence on the clinical effects of sertraline is thought to be negligible.[112][118][131] Based on in vitro studies, sertraline is metabolized by multiple cytochrome 450 isoforms;[130][132] however, it appears that in the human body CYP2C19 plays the most important role, followed by CYP2B6.[133] In addition to the cytochrome P450 system, sertraline can be oxidatively deaminated in vitro by monoamine oxidases;[112] however, this metabolic pathway has never been studied in vivo.[130]

Elimination

The elimination half-life of sertraline is on average 26 hours, with a range of 13 to 45 hours.[112][105] The elimination half-life of desmethylsertraline is 62 to 104 hours.[112]

In a small study of two males, sertraline was excreted to similar degrees in urine and feces (40 to 45% each within 9 days).[112] Unchanged sertraline was not detectable in urine, whereas 12 to 14% of unchanged sertraline was present in feces.[112]

Pharmacogenomics

CYP2C19 and CYP2B6 are thought to be the key cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the metabolism of sertraline.[133] Relative to CYP2C19 normal (extensive) metabolizers, poor metabolizers have 2.7-fold higher levels of sertraline[134] and intermediate metabolizers have 1.4-fold higher levels.[135] In contrast, CYP2B6 poor metabolizers have 1.6-fold higher levels of sertraline and intermediate metabolizers have 1.2-fold higher levels.[133]

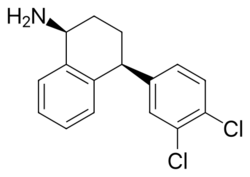

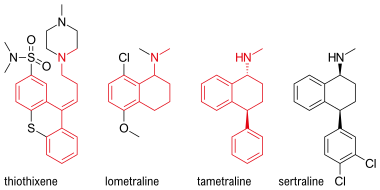

Chemistry

In terms of chemical structure, sertraline is a 1-aminotetralin.[136] Several notable analogues sertraline are known, including desmethylsertraline, dasotraline, tametraline, and lometraline.[136]

History

The history of sertraline dates back to the early 1970s when Pfizer chemist Reinhard Sarges invented a novel series of psychoactive compounds, including lometraline, based on the structures of the neuroleptics thiothixene and pinoxepin.[137][138] Further work on these compounds led to tametraline, a norepinephrine and weaker dopamine reuptake inhibitor. Development of tametraline was soon stopped because of undesired stimulant effects observed in animals. A few years later, in 1977, pharmacologist Kenneth Koe, after comparing the structural features of a variety of reuptake inhibitors, became interested in the tametraline series. He asked another Pfizer chemist, Willard Welch, to synthesize some previously unexplored tametraline derivatives. Welch generated several potent norepinephrine and triple reuptake inhibitors, but to the surprise of the scientists, one representative of the generally inactive cis-analogs was a serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Welch then prepared stereoisomers of this compound, which were tested in vivo by animal behavioral scientist Albert Weissman. The most potent and selective (+)-isomer[lower-alpha 1] was taken into further development and eventually named sertraline. Weissman and Koe recalled that the group did not set up to produce an antidepressant of the SSRI type—in that sense their inquiry was not "very goal driven", and the invention of the sertraline molecule was serendipitous. According to Welch, they worked outside the mainstream at Pfizer, and even "did not have a formal project team". The group had to overcome initial bureaucratic reluctance to pursue sertraline development, as Pfizer was considering licensing an antidepressant candidate from another company.[137][141][142]

Sertraline was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1991 based on the recommendation of the Psychopharmacological Drugs Advisory Committee; it had already become available in the United Kingdom the previous year.[143] The FDA committee achieved a consensus that sertraline was safe and effective for the treatment of major depression. During the discussion, Paul Leber, the director of the FDA Division of Neuropharmacological Drug Products, noted that granting approval was a "tough decision", since the treatment effect on outpatients with depression had been "modest to minimal". Other experts emphasized that the drug's effect on inpatients had not differed from placebo and criticized the poor design of the clinical trials by Pfizer.[144] For example, 40% of participants dropped out of the trials, significantly decreasing their validity.[145]

Until 2002, sertraline was only approved for use in adults ages 18 and over; that year, it was approved by the FDA for use in treating children aged 6 or older with severe OCD. In 2003, the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency issued guidance that, apart from fluoxetine (Prozac), SSRIs are not suitable for the treatment of depression in patients under 18.[146][147] However, sertraline can still be used in the UK for the treatment of OCD in children and adolescents.[148] In 2005, the FDA added a boxed warning concerning pediatric suicidal behavior to all antidepressants, including sertraline. In 2007, labeling was again changed to add a warning regarding suicidal behavior in young adults ages 18 to 24.[149]

Society and culture

Generic availability

The US patent for Zoloft expired in 2006,[150] and sertraline is available in generic form and is marketed under many brand names worldwide.[151]

Brand names

In the US, Zoloft is marketed by Viatris after Upjohn was spun off from Pfizer.[152][153][154]

Interest during COVID-19 pandemic

Sertraline has been the most sought-after antidepressant worldwide before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic, according to Google Trends data. The pandemic has led to an increase in searches for antidepressants, with sertraline, fluoxetine, duloxetine, and venlafaxine showing the highest search volumes, whereas searches of citalopram decreased during the pandemic.[155]

Research

Sertraline may be useful to treat murine Zaire ebolavirus (murine EBOV).[156] The World Health Organization (WHO) considers this a promising area of research.[156]

Lass-Flörl et al., 2003 finds it significantly inhibits phospholipase B in the fungal genus Candida, reducing virulence.[157]

Sertraline is also a very effective leishmanicide.[158] Specifically, Palit & Ali 2008 find that sertraline kills almost all promastigotes of Leishmania donovani.[158]

Sertraline is strongly antibacterial against some species.[158] It is also known to act as a photosensitizer of bacterial surfaces.[159] In combination with antibacterials its photosensitization effect reverses antibacterial resistance.[159] As such sertraline shows promise for food preservation.[159]

Lass-Flörl et al., 2003 finds this compound acts as a fungicide against Candida parapsilosis.[160] Its anti-Cp effect is indeed due to its serotonergic activity and not its other effects.[160]

Sertraline is a promising trypanocide.[161] It acts at several different life stages and against several strains.[161] Sertraline's trypanocidal mechanism of action is by way of interference with bioenergetics.[161]

When mothers take sertraline during pregnancy, there is research evidence that the newborn may experience sertraline withdrawal symptoms.[162]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Sertraline Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. https://www.drugs.com/monograph/sertraline-hydrochloride.html.

- ↑ "Symptom-Onset Dosing of Sertraline for the Treatment of Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial". JAMA Psychiatry 72 (10): 1037–1044. October 2015. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1472. PMID 26351969.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Pharmacotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis". Br J Psychiatry 206 (2): 93–100. February 2015. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.114.148551. PMID 25644881.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Psychotherapy Versus Pharmacotherapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Systemic Review and Meta-Analyses to Determine First-Line Treatments". Depression and Anxiety 33 (9): 792–806. September 2016. doi:10.1002/da.22511. PMID 27126398. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1167&context=usuhs.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use during early pregnancy and congenital malformations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies of more than 9 million births". BMC Med 16 (1). November 2018. doi:10.1186/s12916-018-1193-5. PMID 30415641.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Considering the Risk for Congenital Heart Defects of Antidepressant Classes and Individual Antidepressants". Drug Saf 44 (3): 291–312. March 2021. doi:10.1007/s40264-020-01027-x. ISSN 0114-5916. PMID 33354752. https://unisa.alma.exlibrisgroup.com/view/delivery/61USOUTHAUS_INST/12212569530001831.

- ↑ The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2023. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ↑ "Top 25 Psychiatric Medications for 2016". Psych Central. 12 October 2017. https://psychcentral.com/blog/top-25-psychiatric-medications-for-2016/.

- ↑ "Top 300 of 2023". https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Top300Drugs.aspx.

- ↑ "Sertraline Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2014 - 2023". https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Sertraline.

- ↑ "Medicines in the health system". 2 July 2024. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/medicines/medicines-in-the-health-system.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 12.8 "DailyMed - ZOLOFT- sertraline hydrochloride tablet, film coated ZOLOFT- sertraline hydrochloride solution, concentrate". https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=fe9e8b7d-61ea-409d-84aa-3ebd79a046b5.

- ↑ "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus placebo in patients with major depressive disorder. A systematic review with meta-analysis and Trial Sequential Analysis.". BMC Psychiatry 17 (1). Feb 2017. doi:10.1186/s12888-016-1173-2. PMID 28178949.

- ↑ "Comparative efficacy and acceptability of twenty-one antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". Lancet 391 (10128): 1357–1366. April 2018. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7. PMID 29477251.

- ↑ "What does the latest meta-analysis really tell us about antidepressants?". Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 27 (5): 430–432. Oct 2018. doi:10.1017/S2045796018000240. PMID 29804550.

- ↑ "Should antidepressants be used for major depressive disorder?". BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine 25 (4): 130. August 2020. doi:10.1136/bmjebm-2019-111238. PMID 31554608.

- ↑ "The clinical effectiveness of sertraline in primary care and the role of depression severity and duration (PANDA): a pragmatic, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomised trial". Lancet Psychiatry 6 (11): 903–914. Nov 2019. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30366-9. PMID 31543474.

- ↑ "Sertraline in primary care: comments on the PANDA trial". Lancet Psychiatry 7 (1): 17. Jan 2020. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30381-5. PMID 31860449.

- ↑ "Sertraline in primary care: comments on the PANDA trial". Lancet Psychiatry 7 (1): 18–19. Jan 2020. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30441-9. PMID 31860451.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 "An evidence-based review of the clinical use of sertraline in mood and anxiety disorders". Int Clin Psychopharmacol 24 (2): 43–60. March 2009. doi:10.1097/yic.0b013e3282f4b616. PMID 21456103.

- ↑ "Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): Part I. Practice Preparation, Identification, Assessment, and Initial Management". Pediatrics 141 (3). March 2018. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-4081. PMID 29483200.

- ↑ Depression in children and young people: identification and management: NICE Guideline. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 25 June 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547251/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK547251.pdf.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 "The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor sertraline: its profile and use in psychiatric disorders". CNS Drug Reviews 7 (1): 1–24. 2001. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2001.tb00188.x. PMID 11420570.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". Lancet 373 (9665): 746–58. February 2009. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60046-5. PMID 19185342.; Lay summary in: "Zoloft, Lexapro best new antidepressants-study". Reuters. 28 January 2009. https://www.reuters.com/article/health-depression-idUKLS30284720090129.

- ↑ "A metaanalysis of clinical trials comparing moclobemide with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of major depressive disorder". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 51 (12): 783–90. October 2006. doi:10.1177/070674370605101208. PMID 17168253.

- ↑ "Nefazodone versus sertraline in outpatients with major depression: focus on efficacy, tolerability, and effects on sexual function and satisfaction". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 57 57 (Suppl 2): 53–62. 1996. PMID 8626364.

- ↑ "Double-blind comparison of bupropion sustained release and sertraline in depressed outpatients". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 58 (12): 532–7. December 1997. doi:10.4088/JCP.v58n1204. PMID 9448656.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "The burden of severe depression: a review of diagnostic challenges and treatment alternatives". J Psychiatr Res 41 (3–4): 189–206. 2007. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.05.008. PMID 16870212.

- ↑ For the review, see:"Efficacy and safety of second-generation antidepressants in the treatment of major depressive disorder". Annals of Internal Medicine 143 (6): 415–26. September 2005. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-143-6-200509200-00006. PMID 16172440.

- ↑ "Sertraline versus other antidepressive agents for depression". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4). April 2010. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006117.pub4. PMID 20393946.

- ↑ "Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: A revision of the 2008 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines". J Psychopharmacol 29 (5): 459–525. May 2015. doi:10.1177/0269881115581093. PMID 25969470. https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/ws/files/52545391/PMH_24_3_15_British_Association_forPsychopharmacology_Final_Reconciliation_Draft_2_.docx.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 "World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and posttraumatic stress disorders". World J Biol Psychiatry 3 (4): 171–99. October 2002. doi:10.3109/15622970209150621. PMID 12516310.

- ↑ "Sertraline: a review of its use in the management of major depressive disorder in elderly patients". Drugs & Aging 19 (5): 377–92. 2002. doi:10.2165/00002512-200219050-00006. PMID 12093324.

- ↑ "Comparative efficacy and safety of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors in older adults: a network meta-analysis". J Am Geriatr Soc 19 (63): 1002–1009. 2015. doi:10.1111/jgs.13395. PMID 25945410.

- ↑ "An 8-week multicenter, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of sertraline in elderly outpatients with major depression". The American Journal of Psychiatry 160 (7): 1277–85. July 2003. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1277. PMID 12832242. http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/1777/bf5a7e6a25f2cf957742741b3b14d7677b88.pdf.

- ↑ "Study of the use of antidepressants for depression in dementia: the HTA-SADD trial--a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of sertraline and mirtazapine". Health Technology Assessment 17 (7): 1–166. February 2013. doi:10.3310/hta17070. PMID 23438937.

- ↑ "Antidepressants for children and teenagers: what works for anxiety and depression?". NIHR Evidence (National Institute for Health and Care Research). 3 November 2022. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_53342. https://evidence.nihr.ac.uk/collection/antidepressants-for-children-and-teenagers-what-works-anxiety-depression/.

- ↑ "Antidepressants in Children and Adolescents: Meta-Review of Efficacy, Tolerability and Suicidality in Acute Treatment". Frontiers in Psychiatry 11. 2 September 2020. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00717. PMID 32982805.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 "Efficacy and acceptability of pharmacological, psychosocial, and brain stimulation interventions in children and adolescents with mental disorders: an umbrella review". World Psychiatry 20 (2): 244–275. June 2021. doi:10.1002/wps.20881. PMID 34002501.

- ↑ "Pharmacologic treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: comparative studies". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 58 58 (Suppl 12): 18–22. 1997. PMID 9393392.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 "Canadian clinical practice guidelines for the management of anxiety, posttraumatic stress and obsessive-compulsive disorders". BMC Psychiatry 14 (Suppl 1): S1. 2014. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-14-S1-S1. PMID 25081580.

- ↑ "Issues In The Pharmacological Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: First-Line Treatment Options for OCD". medscape.com. 19 July 2007. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/559370_6.

- ↑ "Pharmacotherapies in the management of obsessive-compulsive disorder". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 51 (7): 417–30. June 2006. doi:10.1177/070674370605100703. PMID 16838823.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 "Sertraline in the treatment of anxiety disorders". Depression and Anxiety 11 (4): 139–57. 2000. doi:10.1002/1520-6394(2000)11:4<139::AID-DA1>3.0.CO;2-C. PMID 10945134.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 "Sex differences in clinical presentation and response in panic disorder: pooled data from sertraline treatment studies". Archives of Women's Mental Health 9 (3): 151–7. May 2006. doi:10.1007/s00737-005-0111-y. PMID 16292466.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 "Sertraline treatment of panic disorder: response in patients at risk for poor outcome". J Clin Psychiatry 61 (12): 922–7. December 2000. doi:10.4088/JCP.v61n1206. PMID 11206597.

- ↑ "Panic disorder and response to sertraline: the effect of previous treatment with benzodiazepines". J Clin Psychopharmacol 21 (1): 104–7. February 2001. doi:10.1097/00004714-200102000-00019. PMID 11199932.

- ↑ "Benzodiazepines in Panic Disorder". Panic Disorder. Springer International Publishing. 2016. pp. 237–253. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-12538-1_16. ISBN 978-3-319-12537-4. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12538-1_16.

- ↑ "New treatment options for panic disorder: clinical trials from 2000 to 2010". Expert Opin Pharmacother 12 (9): 1419–28. June 2011. doi:10.1517/14656566.2011.562200. PMID 21342080.

- ↑ "Efficacy and tolerability of second-generation antidepressants in social anxiety disorder". International Clinical Psychopharmacology 23 (3): 170–9. May 2008. doi:10.1097/YIC.0b013e3282f4224a. PMID 18408531.

- ↑ "Pharmacotherapy of social anxiety disorder: what does the evidence tell us?". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 67 (Suppl 12): 20–6. 2006. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.002. PMID 17092192.

- ↑ "Social anxiety disorder". Lancet 371 (9618): 1115–25. March 2008. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60488-2. PMID 18374843.

- ↑ "World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of personality disorders". World J Biol Psychiatry 8 (4): 212–44. 2007. doi:10.1080/15622970701685224. PMID 17963189.

- ↑ "Enduring effects for cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of depression and anxiety". Annu Rev Psychol 57: 285–315. 2006. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190044. PMID 16318597.

- ↑ "Evaluation of the pharmacokinetics, safety and clinical efficacy of sertraline used to treat social anxiety". Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 9 (11): 1495–505. November 2013. doi:10.1517/17425255.2013.816675. PMID 23834458.

- ↑ "www.nice.org.uk". https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg113/resources/generalised-anxiety-disorder-and-panic-disorder-in-adults-management-pdf-35109387756997.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2024 (8). August 2024. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001396.pub4. PMID 39140320.

- ↑ "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual dysphoric disorder: the emerging gold standard?". Drugs 62 (13): 1869–85. 2002. doi:10.2165/00003495-200262130-00004. PMID 12215058.

- ↑ "Rational treatment choices for non-major depressions in primary care: an evidence-based review". Journal of General Internal Medicine 17 (4): 293–301. April 2002. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10350.x. PMID 11972726.

- ↑ "Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: Epidemiology and Treatment". Curr Psychiatry Rep 17 (11). November 2015. doi:10.1007/s11920-015-0628-3. PMID 26377947.

- ↑ "www.nice.org.uk". https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng116/resources/posttraumatic-stress-disorder-pdf-66141601777861.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 "Long-term pharmacotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder". CNS Drugs 20 (6): 465–76. 2006. doi:10.2165/00023210-200620060-00003. PMID 16734498.

- ↑ "Pharmacologic treatment of rapid ejaculation: levels of evidence-based review". Current Clinical Pharmacology 1 (3): 243–54. September 2006. doi:10.2174/157488406778249352. PMID 18666749.

- ↑ "Premature ejaculation: state of the art". The Urologic Clinics of North America 34 (4): 591–9, vii–viii. November 2007. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2007.08.011. PMID 17983899.

- ↑ "Is Sertraline a Good Pharmacological Strategy to Control Anger? Results of a Systematic Review". Behavioral Sciences 9 (5): 57. May 2019. doi:10.3390/bs9050057. PMID 31126061.

- ↑ "A comparative review of escitalopram, paroxetine, and sertraline: Are they all alike?". International Clinical Psychopharmacology 29 (4): 185–96. July 2014. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000023. PMID 24424469.

- ↑ "Fluoxetine versus sertraline and paroxetine in major depressive disorder: changes in weight with long-term treatment". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61 (11): 863–7. November 2000. doi:10.4088/JCP.v61n1109. PMID 11105740.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 "Weight gain during long-term treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a prospective comparison between serotonin reuptake inhibitors". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65 (10): 1365–71. October 2004. doi:10.4088/JCP.v65n1011. PMID 15491240.

- ↑ "Non-serotonergic pharmacological profiles and associated cognitive effects of serotonin reuptake inhibitors". Journal of Psychopharmacology 15 (3): 173–9. September 2001. doi:10.1177/026988110101500304. PMID 11565624.

- ↑ "Effects of sertraline on autonomic and cognitive functions in healthy volunteers". Psychopharmacology 168 (3): 293–8. July 2003. doi:10.1007/s00213-003-1448-4. PMID 12692706.

- ↑ "Cognitive performance in depressed patients after chronic use of antidepressants". Psychopharmacology 185 (1): 84–92. March 2006. doi:10.1007/s00213-005-0274-2. PMID 16485140.

- ↑ "The influence of sertraline on attention and verbal memory in children and adolescents with anxiety disorders". Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 15 (4): 608–18. August 2005. doi:10.1089/cap.2005.15.608. PMID 16190792.

- ↑ "[The effect of sertraline on cognitive functions in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder]". Psychiatria Polska 36 (6 Suppl): 289–95. 2002. PMID 12647451.

- ↑ "Additional dopamine reuptake inhibition attenuates vigilance impairment induced by serotonin reuptake inhibition in man". Journal of Psychopharmacology 16 (3): 207–14. September 2002. doi:10.1177/026988110201600303. PMID 12236626. https://cris.maastrichtuniversity.nl/en/publications/3ff8af50-7c4a-4dc0-84a1-35e697e6ef8e.

- ↑ "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) use during pregnancy and effects on the fetus and newborn: a meta-analysis". Journal of Perinatology 25 (9): 595–604. September 2005. doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7211352. PMID 16015372.

- ↑ "British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus guidance on the use of psychotropic medication preconception, in pregnancy and postpartum 2017". J Psychopharmacol 31 (5): 519–552. May 2017. doi:10.1177/0269881117699361. PMID 28440103. http://orca.cf.ac.uk/102601/1/British%20Association%20for%20Psychopharmacology%20consensus%20guidance%20on%20the%20use%20of%20psychotropic%20medication%20preconception.pdf.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant treatment discontinuation syndrome: a review of the clinical evidence and the possible mechanisms involved". Front Pharmacol 4: 45. 2013. doi:10.3389/fphar.2013.00045. PMID 23596418.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 "Withdrawal Symptoms after Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Discontinuation: A Systematic Review". Psychother Psychosom 84 (2): 72–81. 2015. doi:10.1159/000370338. PMID 25721705.

- ↑ "Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome". American Family Physician 74 (3): 449–56. August 2006. PMID 16913164.

- ↑ "Antidepressants and movement disorders: a postmarketing study in the world pharmacovigilance database". BMC Psychiatry 20 (1). June 2020. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02711-z. PMID 32546134.

- ↑ "SSRI-associated bruxism: A systematic review of published case reports". Neurology. Clinical Practice 8 (2): 135–141. April 2018. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000433. PMID 29708207.

- ↑ "Management of microscopic colitis: challenges and solutions". Clin Exp Gastroenterol 12: 111–120. 2019. doi:10.2147/CEG.S165047. PMID 30881078.

- ↑ "The effects of antidepressants on sexual functioning in depressed patients: a review". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 62 62 (Suppl 3): 22–34. 2001. PMID 11229450.

- ↑ "A placebo-controlled comparison of the antidepressant efficacy and effects on sexual functioning of sustained-release bupropion and sertraline". Clinical Therapeutics 21 (4): 643–58. April 1999. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(00)88317-4. PMID 10363731.

- ↑ "Post-SSRI Sexual Dysfunction: A Literature Review". Sexual Medicine Reviews 6 (1): 29–34. January 2018. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.07.002. PMID 28778697.

- ↑ "The FDA "Black Box" Warning on Antidepressant Suicide Risk in Young Adults: More Harm Than Benefits?". Frontiers in Psychiatry 10. 2019. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00294. PMID 31130881.

- ↑ "Antidepressants' black-box warning--10 years later". The New England Journal of Medicine 371 (18): 1666–8. October 2014. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1408480. PMID 25354101.

- ↑ "The FDA warning on antidepressants and suicidality--why the controversy?". The New England Journal of Medicine 371 (18): 1668–71. October 2014. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1411138. PMID 25354102.

- ↑ "Antidepressants and Suicidality in Adults: Statistical Evaluation. (Presentation at Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee; December 13, 2006)". FDA. https://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/06/slides/2006-4272s1-04-FDA.ppt.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 90.2 , Wikidata Q118139691

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 , Wikidata Q118139771

- ↑ Pfizer Inc. (30 November 2006). "Memorandum from Pfizer Global Pharmaceuticals Re: DOCKET: 2006N-0414 –"Suicidality data from adult antidepressant trials" Background package for December 13 Advisory Committee". FDA DOCKET 2006N-0414. FDA. https://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/dockets/06n0414/06N-0414-EC32-Attach-1.pdf.

- ↑ "Report of the CSM expert working group on the safety of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants". MHRA. December 2004. http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/pl-p/documents/drugsafetymessage/con019472.pdf.

- ↑ "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and suicide in adults: meta-analysis of drug company data from placebo controlled, randomised controlled trials submitted to the MHRA's safety review". BMJ 330 (7488): 385. February 2005. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7488.385. PMID 15718537.

- ↑ "Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs" (in en). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=019839.

- ↑ Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, California: Biomedical Publications. 2008. pp. 1399–1400.

- ↑ The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. 2012. ISBN 978-0-470-97948-8.

- ↑ "Suicidal antidepressant overdoses: a comparative analysis by antidepressant type". Journal of Medical Toxicology 4 (4): 238–50. December 2008. doi:10.1007/BF03161207. PMID 19031375.

- ↑ "UpToDate". https://www.uptodate.com/content-not-available.

- ↑ AbbVie (February 2017). "SYNTHROID® (levothyroxine sodium) tablets, for oral use". https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/021402s024s028lbl.pdf.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 "The utility of in vitro cytochrome P450 inhibition data in the prediction of drug–drug interactions". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 316 (1): 336–48. January 2006. doi:10.1124/jpet.105.093229. PMID 16192315.

- ↑ "The extent and determinants of changes in CYP2D6 and CYP1A2 activities with therapeutic doses of sertraline". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 18 (1): 55–61. February 1998. doi:10.1097/00004714-199802000-00009. PMID 9472843.

- ↑ "CYP2D6 status of extensive metabolizers after multiple-dose fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, or sertraline". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 19 (2): 155–63. April 1999. doi:10.1097/00004714-199904000-00011. PMID 10211917.

- ↑ "CYP2D6 inhibition by fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine in a crossover study: intraindividual variability and plasma concentration correlations". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 40 (1): 58–66. January 2000. doi:10.1177/009127000004000108. PMID 10631623.

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 105.2 105.3 105.4 "Clinical pharmacokinetics of sertraline". Clin Pharmacokinet 41 (15): 1247–66. 2002. doi:10.2165/00003088-200241150-00002. PMID 12452737.

- ↑ "Comparison of duloxetine, escitalopram, and sertraline effects on cytochrome P450 2D6 function in healthy volunteers". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 27 (1): 28–34. February 2007. doi:10.1097/00004714-200702000-00005. PMID 17224709.

- ↑ "The effect of sertraline on methadone plasma levels in methadone-maintenance patients". The American Journal on Addictions 9 (1): 63–9. 2000. doi:10.1080/10550490050172236. PMID 10914294.

- ↑ "Cytochrome P450 2B6: function, genetics, and clinical relevance". Drug Metabol Drug Interact 27 (4): 185–197. 2012. doi:10.1515/dmdi-2012-0027. PMID 23152403.

- ↑ The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychopharmacology, Sixth Edition. American Psychiatric Association Publishing. 2024. p. 448. ISBN 978-1-61537-435-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=zKL-EAAAQBAJ&pg=PA448. Retrieved 19 September 2024. "The degree of sertraline's inhibition of the CYP system, most significantly CYP2D6, is relatively minor compared with that of other SSRIs such as fluoxetine and paroxetine (Preskorn et al. 2007), although mouse data have shown a mild pharmacokinetic drug-drug interaction between bupropion and sertraline that leads to a small elevation in bupropion metabolism (Molnari et al. 2012). Because TCAs are substrates of CYP2D6, drug levels, and dosages must be closely monitored when TCAs are used in combination with sertraline."

- ↑ "Effects of sertraline on the pharmacokinetics of bupropion and its major metabolite, hydroxybupropion, in mice". Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 37 (1): 57–63. March 2012. doi:10.1007/s13318-011-0065-6. PMID 21928040.

- ↑ "Comparative CYP3A4 inhibitory effects of venlafaxine, fluoxetine, sertraline, and nefazodone in healthy volunteers". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 24 (1): 4–10. February 2004. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000104908.75206.26. PMID 14709940.

- ↑ 112.00 112.01 112.02 112.03 112.04 112.05 112.06 112.07 112.08 112.09 112.10 112.11 112.12 112.13 112.14 112.15 Sertraline FDA Label Last updated May 2014

- ↑ "Coadministration of short-term zolpidem with sertraline in healthy women". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 39 (2): 184–91. February 1999. doi:10.1177/00912709922007624. PMID 11563412.

- ↑ "Elevated serum phenytoin concentrations associated with coadministration of sertraline". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 17 (2): 107–9. April 1997. doi:10.1097/00004714-199704000-00008. PMID 10950473.

- ↑ "Lamotrigine toxicity secondary to sertraline". Seizure 7 (2): 163–5. April 1998. doi:10.1016/S1059-1311(98)80074-5. PMID 9627209.

- ↑ "Effect of proton pump inhibitors on the serum concentrations of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors citalopram, escitalopram, and sertraline". Ther Drug Monit 37 (1): 90–7. February 2015. doi:10.1097/FTD.0000000000000101. PMID 24887634.

- ↑ 117.0 117.1 117.2 117.3 117.4 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedpmid9537821 - ↑ 118.0 118.1 118.2 118.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedpmid9400006 - ↑ 119.0 119.1 119.2 119.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedpmid11543737 - ↑ 120.0 120.1 120.2 120.3 "Binding of antidepressants to human brain receptors: focus on newer generation compounds". Psychopharmacology 114 (4): 559–65. May 1994. doi:10.1007/bf02244985. PMID 7855217.

- ↑ 121.0 121.1 121.2 "The affinity and selectivity of α-adrenoceptor antagonists, antidepressants, and antipsychotics for the human α1A, α1B, and α1D-adrenoceptors". Pharmacol Res Perspect 8 (4). August 2020. doi:10.1002/prp2.602. PMID 32608144.

- ↑ 122.0 122.1 122.2 "Sigma-1 Receptor Agonists and Their Clinical Implications in Neuropsychiatric Disorders". Sigma Receptors: Their Role in Disease and as Therapeutic Targets. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 964. 2017. pp. 153–161. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-50174-1_11. ISBN 978-3-319-50172-7.

- ↑ 123.0 123.1 123.2 123.3 "Cognition and depression: the effects of fluvoxamine, a sigma-1 receptor agonist, reconsidered". Human Psychopharmacology 25 (3): 193–200. April 2010. doi:10.1002/hup.1106. PMID 20373470.

- ↑ "Serotonin and brain function: a tale of two receptors". Journal of Psychopharmacology 31 (9): 1091–1120. September 2017. doi:10.1177/0269881117725915. PMID 28858536.

- ↑ "How do antidepressants work? New perspectives for refining future treatment approaches". The Lancet. Psychiatry 4 (5): 409–418. May 2017. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30015-9. PMID 28153641.

- ↑ "Pharmacology of antidepressants". Mayo Clinic Proceedings 76 (5): 511–27. May 2001. doi:10.4065/76.5.511. PMID 11357798.

- ↑ Pharmacology and Physiology for Anesthesia E-Book: Foundations and Clinical Application. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2012. pp. 183–. ISBN 978-1-4557-3793-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=am_DS7rgypAC&pg=PA183.

- ↑ "Sigma-1 receptors and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: clinical implications of their relationship". Central Nervous System Agents in Medicinal Chemistry 9 (3): 197–204. September 2009. doi:10.2174/1871524910909030197. PMID 20021354.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedPDSP - ↑ 130.0 130.1 130.2 "Sertraline is metabolized by multiple cytochrome P450 enzymes, monoamine oxidases, and glucuronyl transferases in human: an in vitro study". Drug Metabolism and Disposition 33 (2): 262–70. February 2005. doi:10.1124/dmd.104.002428. PMID 15547048.

- ↑ "Comparison of the effects of sertraline and its metabolite desmethylsertraline on blockade of central 5-HT reuptake in vivo". Neuropsychopharmacology 14 (4): 225–231. April 1996. doi:10.1016/0893-133X(95)00112-Q. PMID 8924190.

- ↑ "Sertraline N-demethylation is catalyzed by multiple isoforms of human cytochrome P-450 in vitro". Drug Metabolism and Disposition 27 (7): 763–6. July 1999. doi:10.1016/S0090-9556(24)15222-1. PMID 10383917.

- ↑ 133.0 133.1 133.2 "Effect of Polymorphisms on the Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics and Safety of Sertraline in Healthy Volunteers". Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology 122 (5): 501–511. May 2018. doi:10.1111/bcpt.12938. PMID 29136336.

- ↑ "Impact of CYP2C19 genotype on sertraline exposure in 1200 Scandinavian patients". Neuropsychopharmacology 45 (3): 570–576. February 2020. doi:10.1038/s41386-019-0554-x. PMID 31649299.

- ↑ "Association of CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 Poor and Intermediate Metabolizer Status With Antidepressant and Antipsychotic Exposure: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA Psychiatry 78 (3): 270–280. November 2020. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.3643. PMID 33237321.

- ↑ 136.0 136.1 "Shaping the future of medicine through diverse therapeutic applications of tetralin derivatives". Medicinal Chemistry Research 34 (1): 86–113. 2025. doi:10.1007/s00044-024-03331-y. ISSN 1054-2523. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/385559544.

- ↑ 137.0 137.1 Discovery and Development of Sertraline. Advances in Medicinal Chemistry. 3. 1995. pp. 113–148. doi:10.1016/S1067-5698(06)80005-2. ISBN 978-1-55938-798-9.

- ↑ "5,8-Disubstituted 1-aminotetralins. A class of compounds with a novel profile of central nervous system activity". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 16 (9): 1003–11. September 1973. doi:10.1021/jm00267a010. PMID 4795663.

- ↑ "PharmGKB summary: sertraline pathway, pharmacokinetics". Pharmacogenetics and Genomics 30 (2): 26–33. February 2020. doi:10.1097/FPC.0000000000000392. PMID 31851125.

- ↑ U.S. Patent 4,556,676

- ↑ See also: "ACS Award for Team Innovation". Chemical & Engineering News 84 (5): 45–52. 2006. doi:10.1021/cen-v084n010.p045.

- ↑ A short blurb on the history of sertraline, see: "The brains behind blockbusters". Science 309 (5735): 728. July 2005. doi:10.1126/science.309.5735.728. PMID 16051786.

- ↑ The Antidepressant Era. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 1999. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-674-03958-2.

- ↑ "Minutes of the 33rd Meeting of Psychopharmacological Drugs Advisory Committee on November 19, 1990". FDA. 1990. http://www.healyprozac.com/PDAC/PDAC-Zoloft%20Nov%2090.pdf.

- ↑ See also:"Sertraline safety and efficacy in major depression: a double-blind fixed-dose comparison with placebo". Biological Psychiatry 38 (9): 592–602. November 1995. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(95)00178-8. PMID 8573661.

- ↑ "Safety review of antidepressants used by children completed". MHRA. 10 December 2003. http://www.mhra.gov.uk/NewsCentre/Pressreleases/CON002045.

- ↑ "Drugs for depressed children banned". The Guardian. 10 December 2003. https://www.theguardian.com/uk_news/story/0,3604,1103563,00.html.

- ↑ "Overview of regulatory status and CSM advice relating to major depressive disorder in children and adolescents". MHRA. http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Safetyinformation/Safetywarningsalertsandrecalls/Safetywarningsandmessagesformedicines/CON019494.

- ↑ Food and Drug Administration (2 May 2007). "FDA Proposes New Warnings About Suicidal Thinking, Behavior in Young Adults Who Take Antidepressant Medications". https://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2007/NEW01624.html.

- ↑ "Pfizer needs more drugs". CNN. 17 July 2006. https://money.cnn.com/2006/07/17/news/companies/pfizer/index.htm.

- ↑ "Sertraline international". https://www.drugs.com/international/sertraline.html.

- ↑ "Pfizer Completes Transaction to Combine Its Upjohn Business with Mylan". Pfizer. 16 November 2020. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20201116005378/en/.

- ↑ "Zoloft". https://www.pfizer.com/products/product-detail/zoloft.

- ↑ "Brands". 16 November 2020. https://www.viatris.com/en/products/brands.

- ↑ "The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Interest in Antidepressants: An Analysis of Worldwide Internet Searches With Google Trends Data". Cureus 15 (9). September 2023. doi:10.7759/cureus.45558. PMID 37731683.

- ↑ 156.0 156.1

Slovene pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Thai pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Neukirch, Jürgen; Schmidt, Alexander; Wingberg, Kay (2000), Cohomology of Number Fields, Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften, 323, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-66671-4Template:ScribuntoPersian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]{| class="wikitable" width="100%" This page may be too long to read and navigate comfortably.

This page may be too long to read and navigate comfortably.! rowspan="3" colspan="2" width="14%" style="border-bottom:2px solid grey;" | Date/Time (UTC) ! Configuration ! Serial number ! Launch site ! Outcome |-

|style="text-align:center;background-color:#e3e9e9;" | Payload |style="text-align:center;background-color:#e3e9e9;" | Separation orbit |style="text-align:center;background-color:#e3e9e9;" | Operator |style="text-align:center;background-color:#e3e9e9;" | Function |- | colspan="4" style="text-align:center;background-color:#e4dfdf;border-bottom:2px solid grey;" | Remarks |-

Parameter 1=time required!Hawaiian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]German pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Dutch pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Belarusian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Catalan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]{{{1}}}Mongolian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Javanese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]

This template does not display in the mobile view of Wikipedia; it is desktop only. See Template:Navbox visibility for a brief explanation. This is a navigational template created using {{navbox}}. It can be transcluded on pages by placing

{{Sertraline}}below the standard article appendices.Initial visibility

This template's initial visibility currently defaults to

autocollapse, meaning that if there is another collapsible item on the page (a navbox, sidebar, or table with the collapsible attribute), it is hidden apart from its title bar; if not, it is fully visible.To change this template's initial visibility, the

|state=parameter may be used:{{Sertraline|state=collapsed}}will show the template collapsed, i.e. hidden apart from its title bar.{{Sertraline|state=expanded}}will show the template expanded, i.e. fully visible.

Templates using the classes

class=navbox({{navbox}}) orclass=nomobile({{sidebar}}) are not displayed in article space on the mobile web site of English Wikipedia. Mobile page views accounted for 60% to 70% of all page views from 2020 through 2025. Briefly, these templates are not included in articles because 1) they are not well designed for mobile, and 2) they significantly increase page sizes—bad for mobile downloads—in a way that is not useful for the mobile use case. You can review/watch phab:T124168 for further discussion.TemplateData

A navigational box that can be placed at the bottom of articles.

Template parameters[Edit template data]

Parameter Description Type Status State stateThe initial visibility of the navbox

- Suggested values

collapsedexpandedautocollapse

String suggested Template transclusions

Transclusion maintenance Check completeness of transclusions  Not doneLatin pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]

Not doneLatin pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]

| rowspan="1" colspan="2" style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" |

| style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" | | style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" | | style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" | | style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" |

|-

|-

Vietnamese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Piedmontese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Slovak pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]text-align: auto;Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "{"./Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "{". (age Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "{".–Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "{".)Occitan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]data-sort-value="" style="background: #ececec; color: #2C2C2C; vertical-align: middle; font-size: smaller; text-align: center; " class="table-na" | VariesHejazi pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Spanish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Portuguese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Irish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Mayan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Nahuatl pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Kyrgyz pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Scottish Gaelic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Ukrainian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Burmese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Hindi pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]-4500 —–-4000 —–-3500 —–-3000 —–-2500 —–-2000 —–-1500 —–-1000 —–-500 —–0 — Done

Done To doRussian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Greek pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]

To doRussian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Greek pronunciation: [{{{1}}}] Danish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Northern Sami pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Mandarin pronunciation: [{{{ipa}}}]Cantonese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Entry from Sertraline from TCI Europe, retrieved on {{{Date}}}Chambers, Robert; Thomson, Thomas Napier (1857). "[[s:A biographical dictionary of eminent Scotsmen/|]]". A Biographical Dictionary of Eminent Scotsmen. Glasgow: Blackie and Son.{{{1}}}Polish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Malagasy pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Japanese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Armenian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Czech pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]∶Manx pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/full/{{{1}}}/0 Alemannic German pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Tagalog pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Egyptian Arabic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]French pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Error: Invalid time.

Danish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Northern Sami pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Mandarin pronunciation: [{{{ipa}}}]Cantonese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Entry from Sertraline from TCI Europe, retrieved on {{{Date}}}Chambers, Robert; Thomson, Thomas Napier (1857). "[[s:A biographical dictionary of eminent Scotsmen/|]]". A Biographical Dictionary of Eminent Scotsmen. Glasgow: Blackie and Son.{{{1}}}Polish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Malagasy pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Japanese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Armenian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Czech pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]∶Manx pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/full/{{{1}}}/0 Alemannic German pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Tagalog pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Egyptian Arabic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]French pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Error: Invalid time.

This template does not display in the mobile view of Wikipedia; it is desktop only. See Template:Navbox visibility for a brief explanation. This is a navigational template created using {{navbox}}. It can be transcluded on pages by placing

{{Sertraline}}below the standard article appendices.Initial visibility

This template's initial visibility currently defaults to

autocollapse, meaning that if there is another collapsible item on the page (a navbox, sidebar, or table with the collapsible attribute), it is hidden apart from its title bar; if not, it is fully visible.To change this template's initial visibility, the

|state=parameter may be used:{{Sertraline|state=collapsed}}will show the template collapsed, i.e. hidden apart from its title bar.{{Sertraline|state=expanded}}will show the template expanded, i.e. fully visible.

Templates using the classes

class=navbox({{navbox}}) orclass=nomobile({{sidebar}}) are not displayed in article space on the mobile web site of English Wikipedia. Mobile page views accounted for 60% to 70% of all page views from 2020 through 2025. Briefly, these templates are not included in articles because 1) they are not well designed for mobile, and 2) they significantly increase page sizes—bad for mobile downloads—in a way that is not useful for the mobile use case. You can review/watch phab:T124168 for further discussion.TemplateData

A navigational box that can be placed at the bottom of articles.

Template parameters[Edit template data]

Parameter Description Type Status State stateThe initial visibility of the navbox

- Suggested values

collapsedexpandedautocollapse

String suggested  In progressPalomares, M. L. D. and Pauly, D., eds. (2011). "{{{1}}} {{{2}}}" in SeaLifeBase. April 2011 version.Turkish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Finnish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2006). "{{{1}}} {{{2}}}" in FishBase. April 2006 version.

In progressPalomares, M. L. D. and Pauly, D., eds. (2011). "{{{1}}} {{{2}}}" in SeaLifeBase. April 2011 version.Turkish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Finnish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2006). "{{{1}}} {{{2}}}" in FishBase. April 2006 version.

|- | ... | — | — | — | — | — | —

|-Old Norse pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Salish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Basque pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]{{{1}}}data-sort-value="" style="background: #ececec; color: #2C2C2C; vertical-align: middle; font-size: smaller; text-align: center; " class="table-na" | UnreleasedNorwegian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}] (aged {{{4}}})Hungarian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Quechua pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Arabic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Punjabi pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Afrikaans pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Romanian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Hebrew pronunciation: [{{{1}}}][INVALID OR MISSING PARAMETER IN TEMPLATE Sertraline]Uto-Aztecan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Tamil pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Hindustani pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Swedish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Kazakh pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Lao pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Tibetan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Khmer pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]data-sort-value="" style="vertical-align:middle; text-align:center" class="table-na" | —{{{1}}}Welsh pronunciation: [{{{1}}}] Partially doneAthabaskan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Māori pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]IPA: [{{{1}}}]Bulgarian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Korean pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Icelandic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Sanskrit pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Bengali pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Indonesian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Serbo-Croatian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]CROSBI {{{1}}} "Will There Be a Cure for Ebola?". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology (Annual Reviews) 57 (1): 329–348. January 2017. doi:10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010716-105055. PMID 27959624.

Partially doneAthabaskan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Māori pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]IPA: [{{{1}}}]Bulgarian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Korean pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Icelandic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Sanskrit pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Bengali pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Indonesian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Serbo-Croatian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]CROSBI {{{1}}} "Will There Be a Cure for Ebola?". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology (Annual Reviews) 57 (1): 329–348. January 2017. doi:10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010716-105055. PMID 27959624.

Slovene pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Thai pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Neukirch, Jürgen; Schmidt, Alexander; Wingberg, Kay (2000), Cohomology of Number Fields, Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften, 323, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-66671-4Template:ScribuntoPersian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]{| class="wikitable" width="100%" This page may be too long to read and navigate comfortably.

This page may be too long to read and navigate comfortably.! rowspan="3" colspan="2" width="14%" style="border-bottom:2px solid grey;" | Date/Time (UTC) ! Configuration ! Serial number ! Launch site ! Outcome |-

|style="text-align:center;background-color:#e3e9e9;" | Payload |style="text-align:center;background-color:#e3e9e9;" | Separation orbit |style="text-align:center;background-color:#e3e9e9;" | Operator |style="text-align:center;background-color:#e3e9e9;" | Function |- | colspan="4" style="text-align:center;background-color:#e4dfdf;border-bottom:2px solid grey;" | Remarks |-

Parameter 1=time required!Hawaiian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]German pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Dutch pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Belarusian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Catalan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]{{{1}}}Mongolian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Javanese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]

This template does not display in the mobile view of Wikipedia; it is desktop only. See Template:Navbox visibility for a brief explanation. This is a navigational template created using {{navbox}}. It can be transcluded on pages by placing

{{Sertraline}}below the standard article appendices.Initial visibility

This template's initial visibility currently defaults to

autocollapse, meaning that if there is another collapsible item on the page (a navbox, sidebar, or table with the collapsible attribute), it is hidden apart from its title bar; if not, it is fully visible.To change this template's initial visibility, the

|state=parameter may be used:{{Sertraline|state=collapsed}}will show the template collapsed, i.e. hidden apart from its title bar.{{Sertraline|state=expanded}}will show the template expanded, i.e. fully visible.

Templates using the classes

class=navbox({{navbox}}) orclass=nomobile({{sidebar}}) are not displayed in article space on the mobile web site of English Wikipedia. Mobile page views accounted for 60% to 70% of all page views from 2020 through 2025. Briefly, these templates are not included in articles because 1) they are not well designed for mobile, and 2) they significantly increase page sizes—bad for mobile downloads—in a way that is not useful for the mobile use case. You can review/watch phab:T124168 for further discussion.TemplateData

A navigational box that can be placed at the bottom of articles.

Template parameters[Edit template data]

Parameter Description Type Status State stateThe initial visibility of the navbox

- Suggested values

collapsedexpandedautocollapse

String suggested Template transclusions

Transclusion maintenance Check completeness of transclusions  Not doneLatin pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]

Not doneLatin pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]

| rowspan="1" colspan="2" style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" |

| style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" | | style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" | | style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" | | style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" |

|-

|-