Chemistry:Paroxetine

Paroxetine, sold under the brand name Paxil among others, is an antidepressant medication of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class[1] used to treat major depressive disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), generalized anxiety disorder, and premenstrual dysphoric disorder.[1] It has also been used in the treatment of premature ejaculation, and hot flashes due to menopause.[1][2] It is taken orally (by mouth).[1]

Common side effects include drowsiness, dry mouth, loss of appetite, sweating, trouble sleeping, and sexual dysfunction.[1] Serious side effects may include suicidal thoughts in those under the age of 25, serotonin syndrome, and mania.[1] While the rate of side effects appears similar compared to other SSRIs and SNRIs, antidepressant discontinuation syndrome may occur more often.[3][4] Use in pregnancy is not recommended, while use during breastfeeding is relatively safe.[5] It is believed to work by blocking the reuptake of the chemical serotonin by neurons in the brain.[1]

Paroxetine was approved for medical use in the United States in 1992 and initially sold by GlaxoSmithKline.[1][6] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[7] It is available as a generic medication.[8] In 2023, it was the 72nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 9 million prescriptions.[9][10] In 2018, it was in the top 10 of most prescribed antidepressants in the United States.[11]

Medical uses

Paroxetine is primarily used to treat major depressive disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, social anxiety disorder, and panic disorder. It is also occasionally used for agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, and menopausal hot flashes.[12][13][14][15][16]

Depression

A variety of meta-analyses have been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of paroxetine in depression. They have variously concluded that paroxetine is superior to placebo and that it is equivalent to other antidepressants.[17][18][19] Despite this, there was no clear evidence that paroxetine was better or worse compared with other antidepressants at increasing response to treatment at any point in time.[20]

Anxiety disorders

Paroxetine was the first antidepressant approved in the United States for the treatment of panic disorder.[21] Several studies have concluded that paroxetine is superior to placebo in the treatment of panic disorder.[19][22]

Paroxetine has demonstrated efficacy for the treatment of social anxiety disorder in adults and children.[23][24] It is also beneficial for people with co-occurring social anxiety disorder and alcohol use disorder.[25] It appears to be similar to a number of other SSRIs.[26]

Paroxetine is used in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder.[27] Comparative efficacy of paroxetine is equivalent to that of clomipramine and venlafaxine.[28][29] Paroxetine is also effective for children with obsessive-compulsive disorder.[30]

Paroxetine is approved for the treatment of PTSD in the United States, Japan, and Europe.[31][32][33] In the United States, it is approved for short-term use.[32]

Paroxetine is also FDA-approved for generalized anxiety disorder.[34]

Menopausal hot flashes

In 2013, low-dose paroxetine was approved in the US for the treatment of moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms such as hot flashes and night sweats associated with menopause.[2] At the low dose used for menopausal hot flashes, side effects are similar to placebo and dose tapering is not required for discontinuation.[35]

Fibromyalgia

Studies have also shown paroxetine "appears to be well-tolerated and improve the overall symptomatology in patients with fibromyalgia", but is less robust in helping with the pain involved.[36][37]

Adverse effects

Common side effects include drowsiness, dry mouth, loss of appetite, sweating, insomnia, and sexual dysfunction.[1] Serious side effects may include suicide in those under the age of 25, serotonin syndrome, and mania.[1] While the rate of side effects appears similar compared to other SSRIs and SNRIs, antidepressant discontinuation syndromes may occur more often.[3][4] Use in pregnancy is not recommended, while use during breastfeeding is relatively safe.[5]

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), the U.S. agency responsible for regulating civil aviation, considers paroxetine to be an antidepressant medication that is ineligible for an FAA Authorization of Special Issuance (SI) or Special Consideration (SC) of a medical certificate.[38]

Paroxetine shares many of the common adverse effects of SSRIs, including (with the corresponding rates seen in people treated with placebo in parentheses):

- nausea 26% (9%)

- somnolence 23% (9%)

- dry mouth 18% (12%)

- headache 18% (17%)

- asthenia (weakness) 15% (6%)

- constipation 14% (9%)

- dizziness 13% (6%)

- insomnia 13% (6%)

- diarrhea 12% (8%)

- sweating 11% (2%)

- tremor 8% (2%)

- loss of appetite 6% (2%)

- nervousness 5% (3%)

- blurred vision 4% (1%)

- paraesthesia 4% (2%)

- hypomania 1% (0.3%)

- sexual dysfunction (≥10% incidence).[39]

Most of these adverse effects are transient and go away with continued treatment. Central and peripheral 5-HT3 receptor stimulation is believed to result in the gastrointestinal effects observed with SSRI treatment.[40] Compared to other SSRIs, it has a lower incidence of diarrhea, but a higher incidence of anticholinergic effects (e.g., dry mouth, constipation, blurred vision, etc.), sedation/somnolence/drowsiness, sexual side effects, and weight gain.[41]

Due to reports of adverse withdrawal reactions upon terminating treatment, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use at the European Medicines Agency recommends gradually reducing over several weeks or months if the decision to withdraw is made.[42] See also Discontinuation syndrome (withdrawal).

Mania or hypomania may occur in 1% of patients with depression and up to 12% of patients with bipolar disorder.[43] This side effect can occur in individuals with no history of mania, but it may be more likely to occur in those with bipolar disorder or with a family history of mania.[44]

Paroxetine is described as a 'hepatoxic agent'[45] and has been associated with hepatoxicity and jaundice.[46]

Suicide

Like other antidepressants, paroxetine may increase the risk of suicidal thinking and behaviour in people under the age of 25.[47][48] The FDA conducted a statistical analysis of paroxetine clinical trials in children and adolescents in 2004 and found an increase in suicidality and ideation as compared to placebo, which was observed in trials for both depression and anxiety disorders.[49] In 2015, a paper published in The BMJ that reanalysed the original case notes argued that in Study 329,[50] assessing paroxetine and imipramine against placebo in adolescents with depression, the incidence of suicidal behavior had been under-reported and the efficacy exaggerated for paroxetine.[51][52][53][54][55]

Sexual dysfunction

Sexual dysfunction, including loss of libido, anorgasmia, lack of vaginal lubrication, and erectile dysfunction, is one of the most commonly encountered adverse effects of treatment with paroxetine and other SSRIs. While early clinical trials suggested a relatively low rate of sexual dysfunction, more recent studies in which the investigator actively inquires about sexual problems suggest that the incidence is higher than 70%.[56] Symptoms of sexual dysfunction have been reported to persist after discontinuing SSRIs, although this is thought to be occasional.[57][58][59]

Pregnancy

Antidepressant exposure (including paroxetine) is associated with shorter duration of pregnancy (by three days), increased risk of preterm delivery (by 55%), lower birth weight (by 75 g or 2.6 oz), and lower Apgar scores (by <0.4 points).[60][61] The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that for pregnant women and women planning to become pregnant, paroxetine "be avoided, if possible", as it may be associated with increased risk of birth defects.[62][63]

Babies born to women who used paroxetine during the first trimester have an increased risk of cardiovascular malformations, primarily ventricular and atrial septal defects. Unless the benefits of paroxetine justify continuing treatment, consideration should be given to stopping or switching to another antidepressant.[64] Paroxetine use during pregnancy is associated with about 1.5– to 1.7-fold increase in congenital birth defects, in particular, heart defects, cleft lip and palate, clubbed feet, or any birth defects.[65][66][67][68][69]

Discontinuation syndrome

Many psychoactive medications can cause withdrawal symptoms upon discontinuation from administration. Paroxetine has among the highest incidence rates and severity of withdrawal syndrome of any medication of its class.[70] Common withdrawal symptoms for paroxetine include nausea, dizziness, lightheadedness and vertigo; insomnia, nightmares, and vivid dreams; feelings of electricity in the body, as well as rebound depression and anxiety. A liquid formulation of paroxetine is available and allows a very gradual decrease of the dose, which may prevent discontinuation syndrome. Another recommendation is to temporarily switch to fluoxetine, which has a longer half-life and thus decreases the severity of discontinuation syndrome.[71][72][73]

In 2002, the U.S. FDA published a warning regarding "severe" discontinuation symptoms among those terminating paroxetine treatment, including paraesthesia, nightmares, and dizziness. The agency also warned of case reports describing agitation, sweating, and nausea. In connection with a Glaxo spokesperson's statement that withdrawal reactions occur only in 0.2% of patients and are "mild and short-lived", the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Associations said GSK had breached two of the federation's codes of practice.[74]

Paroxetine prescribing information posted at GlaxoSmithKline has been updated related to the occurrence of a discontinuation syndrome, including serious discontinuation symptoms.[64]

Overdose

Acute overdosage is often manifested by vomiting, lethargy, ataxia, tachycardia, and seizures. Plasma, serum, or blood concentrations of paroxetine may be measured to monitor therapeutic administration, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients or to aid in the medicolegal investigation of fatalities. Plasma paroxetine concentrations are generally in a range of 40–400 μg/L in persons receiving daily therapeutic doses and 200–2,000 μg/L in poisoned patients. Postmortem blood levels have ranged from 1–4 mg/L in acute lethal overdose situations.[75][76] Along with the other SSRIs, sertraline and fluoxetine, paroxetine is considered a low-risk drug in cases of overdose.[77]

Interactions

Interactions with other drugs acting on the serotonin system or impairing the metabolism of serotonin may increase the risk of serotonin syndrome or neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS)-like reaction. Such reactions have been observed with SNRIs and SSRIs alone, but particularly with concurrent use of triptans, MAO inhibitors, antipsychotics, or other dopamine antagonists.

The prescribing information states that paroxetine should "not be used in combination with an MAOI (including linezolid, an antibiotic which is a reversible non-selective MAOI), or within 14 days of discontinuing treatment with an MAOI", and should not be used in combination with pimozide, thioridazine, tryptophan, or warfarin.[64]

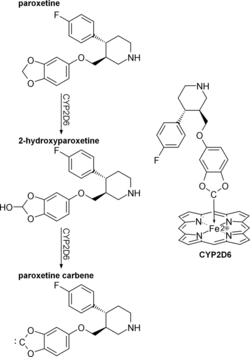

Paroxetine interacts with the following cytochrome P450 enzymes:[41][78]

- CYP2D6 for which it is both a substrate and a potent inhibitor.[79][41]

- CYP2B6 (strong) inhibitor.

- CYP3A4 (weak) inhibitor.

- CYP1A2 (weak) inhibitor.

- CYP2C9 (weak) inhibitor.

- CYP2C19 (weak) inhibitor.

Paroxetine has been shown to be an inhibitor of G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2).[80][81]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Paroxetine is the most potent and one of the most specific selective serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).[83] It also binds to the allosteric site of the serotonin transporter, similarly to escitalopram, though less potently so.[84] Paroxetine also inhibits the reuptake of norepinephrine to a lesser extent (<50 nmol/L).[85] Based on evidence from four weeks of administration in rats, the equivalent of 20 mg paroxetine taken once daily occupies approximately 88% of serotonin transporters in the prefrontal cortex.[78] Paroxetine is a phenylpiperidine and might have some affinity for opioid receptors.[86][87]

| Receptor | Ki (nM) |

|---|---|

| SERT | 0.07 – 0.2 |

| NET | 40 – 85 |

| DAT | 490 |

| D2 | 7,700 |

| 5-HT1A | 21,200 |

| 5-HT2A | 6,300 |

| 5-HT2C | 9,000 |

| α1 | 1,000 – 2,700 |

| α2 | 3,900 |

| M1 | 72 |

| H1 | 13,700 – 23,700 |

Pharmacokinetics

Paroxetine is well-absorbed following oral administration.[78] It has an absolute bioavailability of about 50%, with evidence of a saturable first pass effect.[88] When taken orally, it achieves maximum concentration in about 6–10 hours[78] and reaches steady-state in 7–14 days.[88] Paroxetine exhibits significant interindividual variations in volume of distribution and clearance.[88] Less than 2% of an oral dose is excreted in urine unchanged.[88]

Paroxetine is a mechanism-based inhibitor of CYP2D6.[82][89]

Society and culture

Paroxetine was approved for medical use in the United States in 1992 and initially sold by GlaxoSmithKline.[1][90] It is available as a generic medication.[8] In 2022, it was the 92nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 7 million prescriptions.[91][10] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[7]

GlaxoSmithKline has paid substantial fines, paid settlements in class-action lawsuits, and become the subject of several highly critical books about its marketing of paroxetine, in particular, the off-label marketing of paroxetine for children, the suppression of negative research results relating to its use in children, and allegations that it failed to warn consumers of substantial withdrawal effects associated with the use of the drug.[92][93]

Marketing

In 2004, GSK agreed to settle charges of consumer fraud for $2.5 million.[94] The legal discovery process also uncovered evidence of deliberate, systematic suppression of unfavorable Paxil research results. One of GSK's internal documents read, "It would be commercially unacceptable to include a statement that efficacy [in children] had not been demonstrated, as this would undermine the profile of paroxetine".[95]

In 2012, the United States Department of Justice fined GlaxoSmithKline $3 billion for withholding data, unlawfully promoting use in those under 18, and preparing an article that misleadingly reported the effects of paroxetine in adolescents with depression following its clinical trial study 329.[92][93][96]

In February 2016, the UK Competition and Markets Authority imposed record fines of £45 million on companies that were found to have infringed European Union and UK Competition law by entering into agreements to delay the market entry of generic versions of the drug in the UK. GlaxoSmithKline received the bulk of the fines, being fined £37,600,757. Other companies that produce generics were issued fines which collectively total £7,384,146. UK public health services are likely to claim damages for being overcharged in the period where the generic versions of the drug were illegally blocked from the market, as the generics are over 70% less expensive. GlaxoSmithKline may also face actions from other generic manufacturers who incurred losses as a result of the anticompetitive conduct.[97] In April 2016, appeals were lodged with the Competition Appeal Tribunal by the companies which were fined.[98][99][100][101][102]

GSK marketed paroxetine through television advertisements in the 1990s and 2000s. Commercials also aired for the CR version of the drug beginning in 2003.[103]

Economics

In 2007, paroxetine was ranked 94th on the list of bestselling drugs, with over $1 billion in sales. In 2006, paroxetine was the fifth-most prescribed antidepressant in the U.S. retail market, with more than 19.7 million prescriptions.[104] In 2007, sales had dropped slightly to 18.1 million but paroxetine remained the fifth-most prescribed antidepressant in the U.S.[105][106]

Brand names

Brand names include Aropax, Paretin, Brisdelle, Deroxat, Paxil,[107][108] Pexeva, Paxtine, Paxetin, Paroxat, Paraxyl,[109] Sereupin, Daparox and Seroxat.

Research

Several studies have suggested that paroxetine can be used in the treatment of premature ejaculation. In particular, intravaginal ejaculation latency time (IELT) was found to increase 6- to 13-fold, which was somewhat longer than the delay achieved by the treatment with other SSRIs (fluvoxamine, fluoxetine, sertraline, and citalopram).[110][111][112] However, paroxetine taken acutely ("on demand") 3–10 hours before coitus resulted only in a "clinically irrelevant and sexually unsatisfactory" 1.5-fold delay of ejaculation and was inferior to clomipramine, which induced a fourfold delay.[112]

There is also evidence that paroxetine may be effective in the treatment of compulsive gambling[113] and hot flashes.[114]

Benefits of paroxetine prescription for diabetic neuropathy[115] or chronic tension headache[116] are uncertain.

Although the evidence is conflicting, paroxetine may be effective for the treatment of dysthymia, a chronic disorder involving depressive symptoms for most days of the year.[117]

There is evidence to support that paroxetine selectively binds to and inhibits G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2) in mice with heart failure. Since GRK2 regulates the activity of the beta adrenergic receptor, which becomes desensitized in cases of heart failure, paroxetine (or a paroxetine derivative) could be used as a heart failure treatment in the future.[80][81][118]

Paroxetine has been identified as a potential disease-modifying osteoarthritis drug.[119]

Veterinary use

Paroxetine may be useful in the treatment of canine or feline behavioral diagnoses and is effective in the treatment of social anxiety, depression, and agitation associated with depression.[120]

Other organisms

Paroxetine is a common finding in wastewater.[121] It is highly toxic to the alga Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata (syn. Raphidocelis subcapitata).[121]

It also is toxic to the soil nematode Caenorhabditis elegans.[122]

Alberca et al., 2016 found that paroxetine acts as a trypanocide against T. cruzi.[123]

Alberca et al., 2016 finds a leishmanicide effect.[124] Alberca finds that paroxetine produces cell death of the promastigotes of L. infantum.[124] The mechanism of action remains unknown.[124]

Various types of bacteria can break down paroxetine in the environment. These include, for example Pseudomonas sp., Bosea sp., Shewanella sp., Species of Chitinophagaceae and Acinetobacter sp.[125][126]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 "Paroxetine Hydrochloride Monograph for Professionals". American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. https://www.drugs.com/monograph/paroxetine-hydrochloride.html.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Fischer A (28 June 2013). "FDA approves the first non-hormonal treatment for hot flashes associated with menopause" (Press release). Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "SSRIs and SNRIs: A review of the Discontinuation Syndrome in Children and Adolescents". Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 20 (1): 60–67. February 2011. PMID 21286371.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Paroxetine: current status in psychiatry". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics 7 (2): 107–120. February 2007. doi:10.1586/14737175.7.2.107. PMID 17286545.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Paroxetine Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Drugs.com. https://www.drugs.com/pregnancy/paroxetine.html.

- ↑ Food and Drug Administration (2011). Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations – FDA Orange Book 31st Edition (2011): FDA Orange Book 31st Edition (2011). DrugPatentWatch.com. p. 344. ISBN 978-1-934899-81-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=JDZ4DAAAQBAJ&pg=PR344. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2023. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 British national formulary: BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. pp. 363. ISBN 978-0-85711-338-2.

- ↑ "Top 300 of 2023". https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Top300Drugs.aspx.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Paroxetine Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2023". https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Paroxetine.

- ↑ "Top 25 Psychiatric Medications for 2018". 15 December 2019. https://psychcentral.com/blog/top-25-psychiatric-medications-for-2018/.

- ↑ "Paroxetine: an update of its use in psychiatric disorders in adults". Drugs 62 (4): 655–703. March 2002. doi:10.2165/00003495-200262040-00010. PMID 11893234.

- ↑ "Paroxetine controlled release was effective and tolerable for treating menopausal hot flash symptoms in women". Evidence Based Medicine 9 (1): 23. 1 January 2004. doi:10.1136/ebm.9.1.23. ISSN 1473-6810. http://ebm.bmj.com/content/9/1/23.full. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- ↑ "Paroxetine: an antidepressant". 29 August 2018. https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/paroxetine/.

- ↑ "Paroxetine 20 mg Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (emc)". https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/4168/smpc.

- ↑ "Product and Consumer Medicine Information". Therapeutic Goods Administration. https://www.ebs.tga.gov.au/ebs/picmi/picmirepository.nsf/PICMI?OpenForm&t=&q=paroxetine.

- ↑ "Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". Lancet 373 (9665): 746–758. February 2009. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60046-5. PMID 19185342.

- ↑ "A double-blind study of paroxetine, fluoxetine, and placebo in outpatients with major depression". Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 10 (4): 145–150. December 1998. doi:10.3109/10401239809147030. PMID 9988054.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "The efficacy of paroxetine and placebo in treating anxiety and depression: a meta-analysis of change on the Hamilton Rating Scales". PLOS ONE 9 (8). 27 August 2014. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0106337. PMID 25162656. Bibcode: 2014PLoSO...9j6337S.

- ↑ "Paroxetine versus other anti-depressive agents for depression". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014 (4). April 2014. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006531.pub2. PMID 24696195.

- ↑ Social Work Diagnosis in Contemporary Practice. Oxford University Press US. 2005. ISBN 978-0-19-516878-5.

- ↑ "Double-blind, fixed-dose, placebo-controlled study of paroxetine in the treatment of panic disorder". The American Journal of Psychiatry 155 (1): 36–42. January 1998. doi:10.1176/ajp.155.1.36. PMID 9433336.

- ↑ "Paroxetine treatment of generalized social phobia (social anxiety disorder): a randomized controlled trial". JAMA 280 (8): 708–713. August 1998. doi:10.1001/jama.280.8.708. PMID 9728642.

- ↑ "Paroxetine improves social anxiety disorder in children and adolescents". Evidence-Based Mental Health 8 (2): 43. May 2005. doi:10.1136/ebmh.8.2.43. PMID 15851806. http://ebmh.bmj.com/content/8/2/43.full. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- ↑ "Paroxetine for social anxiety and alcohol use in dual-diagnosed patients". Depression and Anxiety 14 (4): 255–262. 1 January 2001. doi:10.1002/da.1077. PMID 11754136.

- ↑ "The evidence-based pharmacotherapy of social anxiety disorder". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 16 (1): 235–249. February 2013. doi:10.1017/S1461145712000119. PMID 22436306. "There were no significant differences between the three SSRIs that had been tested in placebo-controlled studies: paroxetine; sertraline; fluvoxamine.".

- ↑ "Paroxetine hydrochloride". Profiles of Drug Substances, Excipients, and Related Methodology. Analytical Profiles of Drug Substances and Excipients 38: 367–406. 2013. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-407691-4.00008-3. ISBN 978-0-12-407691-4. PMID 23668408.

- ↑ "Paroxetine versus clomipramine in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. OCD Paroxetine Study Investigators". The British Journal of Psychiatry 169 (4): 468–474. October 1996. doi:10.1192/bjp.169.4.468. PMID 8894198.

- ↑ "A double blind comparison of venlafaxine and paroxetine in obsessive-compulsive disorder". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 23 (6): 568–575. December 2003. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000095342.32154.54. PMID 14624187.

- ↑ "Pharmacotherapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3). July 2009. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005170.pub2. PMID 19588367.

- ↑ "Pharmacotherapy for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder In Combat Veterans: Focus on Antidepressants and Atypical Antipsychotic Agents". P & T 37 (1): 32–38. January 2012. PMID 22346334.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 "Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 15 (6): 825–840. July 2012. doi:10.1017/S1461145711001209. PMID 21798109.

- ↑ "Search results detail| Kusurino-Shiori (Drug information Sheet)". http://www.rad-ar.or.jp/siori/english/kekka.cgi?n=34488.

- ↑ "FDA Approves Antidepressant For Generalized Anxiety Disorder". Psychiatric News 36 (10): 14. 18 May 2001. doi:10.1176/pn.36.10.0014b.

- ↑ "FDA approval of paroxetine for menopausal hot flushes". The New England Journal of Medicine 370 (19): 1777–1779. May 2014. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1402080. PMID 24806158.

- ↑ "A randomized, controlled, trial of controlled release paroxetine in fibromyalgia". The American Journal of Medicine 120 (5): 448–454. May 2007. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.06.006. PMID 17466657.

- ↑ "Efficacy and tolerability of paroxetine in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: a single-blind study". Current Therapeutic Research 60 (12): 696–702. December 1999. doi:10.1016/S0011-393X(99)90008-5.

- ↑ "Guide for Aviation Medical Examiners". 2024-04-24. https://www.faa.gov/ame_guide/app_process/exam_tech/item47/amd/antidepressants. "An individual may be considered for an FAA Authorization of a Special Issuance (SI) or Special Consideration (SC) of a Medical Certificate (Authorization) if: […] 3. The medication used is one of the conditionally acceptable Antidepressant Medications […]."

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMSR - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedGG - ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Pharmacotherapy of Depression (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Humana Press. 2011. doi:10.1007/978-1-60327-435-7. ISBN 978-1-60327-434-0.

- ↑ "Press release, CHMP meeting on Paroxetine and other SSRIs". European Medicines Agency. 9 December 2004. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Press_release/2009/11/WC500015202.pdf.

- ↑ "Prescribing Information Paxil (paroxetine hydrochloride) Tablets and Oral Suspension". http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/020031s067,020710s031.pdf.

- ↑ "Induction of mania in depression by paroxetine". Human Psychopharmacology 18 (7): 565–568. October 2003. doi:10.1002/hup.531. PMID 14533140.

- ↑ "Paroxetine". https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Paroxetine.

- ↑ "Severe hepatotoxicity with jaundice associated with paroxetine". The American Journal of Gastroenterology 96 (8): 2494–2496. August 2001. doi:10.1016/S0002-9270(01)02623-5. PMID 11513198. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0002927001026235.

- ↑ "Medication Guide About Using Antidepressants in Children and Teenagers". FDA. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/drugsafety/informationbydrugclass/UCM161646.pdf.

- ↑ "FDA Launches a Multi-Pronged Strategy to Strengthen Safeguards for Children Treated With Antidepressant Medications". October 15, 2004. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2004/ucm108363.htm.

- ↑ "Review and evaluation of clinical data: relationship between psychotropic drugs and pediatric suicidality". FDA. 16 August 2004. p. 30. https://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/04/briefing/2004-4065b1-10-TAB08-Hammads-Review.pdf.

- ↑ "Efficacy of paroxetine in the treatment of adolescent major depression: a randomized, controlled trial". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 40 (7): 762–772. July 2001. doi:10.1097/00004583-200107000-00010. PMID 11437014.

- ↑ "Restoring Study 329: efficacy and harms of paroxetine and imipramine in treatment of major depression in adolescence". BMJ 351. September 2015. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4320. PMID 26376805.

- ↑ "Study 329". BMJ 351. 17 September 2015. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4973.

- ↑ "No correction, no retraction, no apology, no comment: paroxetine trial reanalysis raises questions about institutional responsibility". BMJ 351. September 2015. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4629. PMID 26377109.

- ↑ "Liberating the data from clinical trials". BMJ 351. September 2015. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4601. PMID 26377210.

- ↑ "Seroxat study under-reported harmful effects on young people, say scientists". The Guardian. 16 September 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2015/sep/16/seroxat-study-harmful-effects-young-people.

- ↑ "Clinical inquiry: How do antidepressants affect sexual function?". The Journal of Family Practice 62 (11): 660–661. November 2013. PMID 24288712.

- ↑ "Persistent sexual dysfunction after discontinuation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors". The Journal of Sexual Medicine 5 (1): 227–233. January 2008. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00630.x. PMID 18173768.

- ↑ "Persistent sexual side effects after SSRI discontinuation". Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 75 (3): 187–188. 2006. doi:10.1159/000091777. PMID 16636635. http://www.mediafire.com/view/hn31cmg4n28bq3x/06_pssd_Csoka.pdf. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- ↑ http://pi.lilly.com/us/prozac.pdf Page 14.

- ↑ "Selected pregnancy and delivery outcomes after exposure to antidepressant medication: a systematic review and meta-analysis". JAMA Psychiatry 70 (4): 436–443. April 2013. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.684. PMID 23446732.

- ↑ "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) use during pregnancy and effects on the fetus and newborn: a meta-analysis". Journal of Perinatology 25 (9): 595–604. September 2005. doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7211352. PMID 16015372.

- ↑ ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice (December 2006). "ACOG Committee Opinion No. 354: Treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy". Obstetrics and Gynecology 108 (6): 1601–1603. doi:10.1097/00006250-200612000-00058. PMID 17138801.

- ↑ "Antidepressant use in pregnant and postpartum women". Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 10: 369–392. 2014. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153626. PMID 24313569.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 "PAXIL (paroxetine hydrochloride) Tablets and Oral Suspension: Prescribing Information". Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline. August 2007. http://us.gsk.com/products/assets/us_paxil.pdf.

- ↑ "Paroxetine use during pregnancy: is it safe?". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy 40 (10): 1834–1837. October 2006. doi:10.1345/aph.1H116. PMID 16926304.

- ↑ "Safety of newer antidepressants in pregnancy". Pharmacotherapy 27 (4): 546–552. April 2007. doi:10.1592/phco.27.4.546. PMID 17381382.

- ↑ "Serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy and the risk of major malformations: a systematic review". Human Psychopharmacology 22 (3): 121–128. April 2007. doi:10.1002/hup.836. PMID 17397101.

- ↑ "The safety of antidepressant drugs during pregnancy". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety 6 (4): 357–370. July 2007. doi:10.1517/14740338.6.4.357. PMID 17688379.

- ↑ "Paroxetine and congenital malformations: meta-Analysis and consideration of potential confounding factors". Clinical Therapeutics 29 (5): 918–926. May 2007. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.05.003. PMID 17697910.

- ↑ "Withdrawal Symptoms after Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Discontinuation: A Systematic Review". Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 84 (2): 72–81. 2015. doi:10.1159/000370338. PMID 25721705.

- ↑ "Antidepressant discontinuation syndromes". Drug Safety 24 (3): 183–197. March 2001. doi:10.2165/00002018-200124030-00003. PMID 11347722.

- ↑ "Recognising and managing antidepressant discontinuation symptoms". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 13 (6): 447–457. November 2007. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.105.001966.

- ↑ "Dependence on Antidepressants & Halting SSRIs". http://www.benzo.org.uk/healy.htm.

- ↑ "Withdrawal from paroxetine can be severe, warns FDA". BMJ 324 (7332): 260. February 2002. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7332.260. PMID 11823353.

- ↑ "Postmortem forensic toxicology of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a review of pharmacology and report of 168 cases". Journal of Forensic Sciences 45 (3): 633–648. May 2000. doi:10.1520/JFS14740J. PMID 10855970.

- ↑ R. Baselt,Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 1190–1193.

- ↑ "Suicidal antidepressant overdoses: a comparative analysis by antidepressant type". Journal of Medical Toxicology 4 (4): 238–250. December 2008. doi:10.1007/BF03161207. PMID 19031375.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 78.2 78.3 "A comparative review of escitalopram, paroxetine, and sertraline: Are they all alike?". International Clinical Psychopharmacology 29 (4): 185–196. July 2014. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000023. PMID 24424469.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedTGA - ↑ 80.0 80.1 "Paroxetine is a direct inhibitor of g protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 and increases myocardial contractility". ACS Chemical Biology 7 (11): 1830–1839. November 2012. doi:10.1021/cb3003013. PMID 22882301.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 "Structure-Based Design of Highly Selective and Potent G Protein-Coupled Receptor Kinase 2 Inhibitors Based on Paroxetine". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 60 (7): 3052–3069. April 2017. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00112. PMID 28323425.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 "Metabolism-guided drug design". MedChemComm 4 (4): 631. 2013. doi:10.1039/C2MD20317K.

- ↑ "High affinity binding of 3H-paroxetine and 3H-imipramine to rat neuronal membranes". Psychopharmacology 89 (4): 436–439. July 1986. doi:10.1007/BF02412117. PMID 2944152.

- ↑ "Allosteric modulation of the effect of escitalopram, paroxetine and fluoxetine: in-vitro and in-vivo studies". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 10 (1): 31–40. February 2007. doi:10.1017/S1461145705006462. PMID 16448580.

- ↑ "[Second generation SSRIS: human monoamine transporter binding profile of escitalopram and R-fluoxetine]". L'Encephale 28 (4): 350–355. 1 August 2002. PMID 12232544.

- ↑ "Paroxetine Increases δ Opioid Responsiveness in Sensory Neurons". eNeuro 9 (4). 2022. doi:10.1523/ENEURO.0063-22.2022. PMID 35882549. ""Paroxetine is a phenylpiperidine and nearly all phenylpiperidines used clinically in research capacities are opioids. Interestingly, this structure is part of the morphine and fentanyl molecules. Furthermore, paroxetine-induced analgesia is dose dependently reversed by opioid receptor antagonists"".

- ↑ "Possible Involvement of Opioidergic and Serotonergic Mechanisms in Antinociceptive Effect of Paroxetine in Acute Pain". Journal of Pharmacological Sciences 94 (2): 161–165. 2004. doi:10.1254/jphs.94.161. PMID 14978354. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1347861319325216. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 88.2 88.3 "A review of the metabolism and pharmacokinetics of paroxetine in man". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum 350: 60–75. 1989. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb07176.x. PMID 2530793.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 "Identification of cytochrome P450 isoforms involved in the metabolism of paroxetine and estimation of their importance for human paroxetine metabolism using a population-based simulator". Drug Metabolism and Disposition 38 (3): 376–385. March 2010. doi:10.1124/dmd.109.030551. PMID 20007670.

- ↑ Food and Drug Administration (2011). Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations – FDA Orange Book 31st Edition (2011): FDA Orange Book 31st Edition (2011). DrugPatentWatch.com. p. 344. ISBN 978-1-934899-81-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=JDZ4DAAAQBAJ&pg=PR344. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ↑ "The Top 300 of 2022". https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Top300Drugs.aspx.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 "GlaxoSmithKline to Plead Guilty and Pay $3 Billion to Resolve Fraud Allegations and Failure to Report Safety Data" (Press release). United States Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs. 2 July 2012. Archived from the original on 9 September 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

The United States alleges that, among other things, GSK participated in preparing, publishing and distributing a misleading medical journal article that misreported that a clinical trial of Paxil demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of depression in patients under age 18, when the study failed to demonstrate efficacy.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 United States ex rel. Greg Thorpe, et al. v. GlaxoSmithKline PLC, and GlaxoSmithKline LLC, pp. 3–19 (D. Mass. 26 October 2011). Text

- ↑ "Drug Companies & Doctors: A Story of Corruption". New York Review of Books 56 (1). 15 January 2009.

- ↑ "Drug company experts advised staff to withhold data about SSRI use in children". CMAJ 170 (5): 783. March 2004. doi:10.1503/cmaj.1040213. PMID 14993169.

- ↑ "Glaxo Agrees to Pay $3 Billion in Fraud Settlement". The New York Times. 2 July 2012. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/03/business/glaxosmithkline-agrees-to-pay-3-billion-in-fraud-settlement.html.

- ↑ "CMA fines pharma companies £45 million". https://www.gov.uk/government/news/cma-fines-pharma-companies-45-million.

- ↑ "GlaxoSmithKline Summary". http://www.catribunal.org.uk/files/1252_GlaxoSmithKline_Summary_180416.pdf.

- ↑ "Generics Summary". http://www.catribunal.org.uk/files/1251_Generics_Summary_180416.pdf.

- ↑ "Xellia Summary". http://www.catribunal.org.uk/files/1253_Xellia_Summary_180416.pdf.

- ↑ "Merck Summary". http://www.catribunal.org.uk/files/1255_Merck_Summary_180416.pdf.

- ↑ "Actavis Summary". http://www.catribunal.org.uk/files/1254_Actavis_Summary_180416.pdf.

- ↑ "Paxil CR -- Nametag -- (2003) :30 (USA) | Adland". 3 April 2004. https://adland.tv/adnews/paxil-cr-nametag-2003-30-usa.

- ↑ The paroxetine prescriptions were calculated as a total of prescriptions for Paxil CR and generic paroxetine using data from the charts for generic and brand-name drugs."Top 200 generic drugs by units in 2006. Top 200 brand-name drugs by units". http://www.drugtopics.com/drugtopics/article/articleDetail.jsp?id=407652.

- ↑ The paroxetine prescriptions were calculated as a total of prescriptions for Paxil CR and generic paroxetine using data from the charts for generic and brand-name drugs."Top 200 generic drugs by units in 2007". 18 February 2008. http://drugtopics.modernmedicine.com/drugtopics/Top200Drugs/ArticleStandard/article/detail/491194.

- ↑ "Top 200 brand drugs by units in 2007". http://drugtopics.modernmedicine.com/drugtopics/PharmacyFactsAndFigures/ArticleStandard/article/detail/491210.

- ↑ "Paroxetine-The Antidepressant from Hell? Probably Not, But Caution Required". Psychopharmacology Bulletin 46 (1): 77–104. March 2016. PMID 27738376.

- ↑ Dictionary of Psychology (Second ed.). Oxford University Press. 2006. p. 552.

- ↑ Dictionary of Psychology (Second ed.). Oxford University Press. 2006. p. 161.

- ↑ "Effect of SSRI antidepressants on ejaculation: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study with fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, and sertraline". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 18 (4): 274–281. August 1998. doi:10.1097/00004714-199808000-00004. PMID 9690692.

- ↑ "SSRIs and ejaculation: a double-blind, randomized, fixed-dose study with paroxetine and citalopram". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 21 (6): 556–560. December 2001. doi:10.1097/00004714-200112000-00003. PMID 11763001.

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 "On-demand treatment of premature ejaculation with clomipramine and paroxetine: a randomized, double-blind fixed-dose study with stopwatch assessment". European Urology 46 (4): 510–5; discussion 516. October 2004. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2004.05.005. PMID 15363569.

- ↑ "A double-blind placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of paroxetine in the treatment of pathological gambling". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 63 (6): 501–507. June 2002. doi:10.4088/JCP.v63n0606. PMID 12088161.

- ↑ "A pilot trial of paroxetine for the treatment of hot flashes and associated symptoms in women with breast cancer". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 23 (4): 337–345. April 2002. doi:10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00379-2. PMID 11997203.

- ↑ "The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor paroxetine is effective in the treatment of diabetic neuropathy symptoms". Pain 42 (2): 135–144. August 1990. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(90)91157-E. PMID 2147235.

- ↑ "Sulpiride and paroxetine in the treatment of chronic tension-type headache. An explanatory double-blind trial". Headache 34 (1): 20–24. January 1994. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1994.hed3401020.x. PMID 8132436.

- ↑ "Comparative benefits and harms of second-generation antidepressants: background paper for the American College of Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine 149 (10): 734–750. November 2008. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-149-10-200811180-00008. PMID 19017592.

- ↑ "Common antidepressant may hold key to heart failure reversal". https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/03/150304152607.htm.

- ↑ "Paroxetine-mediated GRK2 inhibition is a disease-modifying treatment for osteoarthritis". Science Translational Medicine 13 (580). February 2021. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aau8491. PMID 33568523.

- ↑ "Pharmacological Treatment in Behavioural Medicine: The Importance of Neurochemistry, Molecular Biology and Mechanistic Hypotheses". The Veterinary Journal 162 (1): 9–23. 2001. doi:10.1053/tvjl.2001.0568. PMID 11409925.

- ↑ 121.0 121.1

Slovene pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Thai pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Neukirch, Jürgen; Schmidt, Alexander; Wingberg, Kay (2000), Cohomology of Number Fields, Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften, 323, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-66671-4Template:ScribuntoPersian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]{| class="wikitable" width="100%" This page may be too long to read and navigate comfortably.

This page may be too long to read and navigate comfortably.! rowspan="3" colspan="2" width="14%" style="border-bottom:2px solid grey;" | Date/Time (UTC) ! Configuration ! Serial number ! Launch site ! Outcome |-

|style="text-align:center;background-color:#e3e9e9;" | Payload |style="text-align:center;background-color:#e3e9e9;" | Separation orbit |style="text-align:center;background-color:#e3e9e9;" | Operator |style="text-align:center;background-color:#e3e9e9;" | Function |- | colspan="4" style="text-align:center;background-color:#e4dfdf;border-bottom:2px solid grey;" | Remarks |-

Parameter 1=time required!Hawaiian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]German pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Dutch pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Belarusian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Catalan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]{{{1}}}Mongolian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Javanese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]

This template does not display in the mobile view of Wikipedia; it is desktop only. See Template:Navbox visibility for a brief explanation. This is a navigational template created using {{navbox}}. It can be transcluded on pages by placing

{{Paroxetine}}below the standard article appendices.Initial visibility

This template's initial visibility currently defaults to

autocollapse, meaning that if there is another collapsible item on the page (a navbox, sidebar, or table with the collapsible attribute), it is hidden apart from its title bar; if not, it is fully visible.To change this template's initial visibility, the

|state=parameter may be used:{{Paroxetine|state=collapsed}}will show the template collapsed, i.e. hidden apart from its title bar.{{Paroxetine|state=expanded}}will show the template expanded, i.e. fully visible.

Templates using the classes

class=navbox({{navbox}}) orclass=nomobile({{sidebar}}) are not displayed in article space on the mobile web site of English Wikipedia. Mobile page views accounted for 60% to 70% of all page views from 2020 through 2025. Briefly, these templates are not included in articles because 1) they are not well designed for mobile, and 2) they significantly increase page sizes—bad for mobile downloads—in a way that is not useful for the mobile use case. You can review/watch phab:T124168 for further discussion.TemplateData

A navigational box that can be placed at the bottom of articles.

Template parameters[Edit template data]

Parameter Description Type Status State stateThe initial visibility of the navbox

- Suggested values

collapsedexpandedautocollapse

String suggested Template transclusions

Transclusion maintenance Check completeness of transclusions  Not doneLatin pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]

Not doneLatin pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]

| rowspan="1" colspan="2" style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" |

| style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" | | style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" | | style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" | | style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" |

|-

|-

Vietnamese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Piedmontese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Slovak pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]text-align: auto;Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "{"./Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "{". (age Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "{".–Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "{".)Occitan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]data-sort-value="" style="background: #ececec; color: #2C2C2C; vertical-align: middle; font-size: smaller; text-align: center; " class="table-na" | VariesHejazi pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Spanish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Portuguese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Irish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Mayan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Nahuatl pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Kyrgyz pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Scottish Gaelic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Ukrainian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Burmese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Hindi pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]-4500 —–-4000 —–-3500 —–-3000 —–-2500 —–-2000 —–-1500 —–-1000 —–-500 —–0 — Done

Done To doRussian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Greek pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]

To doRussian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Greek pronunciation: [{{{1}}}] Danish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Northern Sami pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Mandarin pronunciation: [{{{ipa}}}]Cantonese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Entry from Paroxetine from TCI Europe, retrieved on {{{Date}}}Chambers, Robert; Thomson, Thomas Napier (1857). "[[s:A biographical dictionary of eminent Scotsmen/|]]". A Biographical Dictionary of Eminent Scotsmen. Glasgow: Blackie and Son.{{{1}}}Polish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Malagasy pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Japanese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Armenian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Czech pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]∶Manx pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/full/{{{1}}}/0 Alemannic German pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Tagalog pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Egyptian Arabic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]French pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Error: Invalid time.

Danish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Northern Sami pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Mandarin pronunciation: [{{{ipa}}}]Cantonese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Entry from Paroxetine from TCI Europe, retrieved on {{{Date}}}Chambers, Robert; Thomson, Thomas Napier (1857). "[[s:A biographical dictionary of eminent Scotsmen/|]]". A Biographical Dictionary of Eminent Scotsmen. Glasgow: Blackie and Son.{{{1}}}Polish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Malagasy pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Japanese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Armenian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Czech pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]∶Manx pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/full/{{{1}}}/0 Alemannic German pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Tagalog pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Egyptian Arabic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]French pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Error: Invalid time.

This template does not display in the mobile view of Wikipedia; it is desktop only. See Template:Navbox visibility for a brief explanation. This is a navigational template created using {{navbox}}. It can be transcluded on pages by placing

{{Paroxetine}}below the standard article appendices.Initial visibility

This template's initial visibility currently defaults to

autocollapse, meaning that if there is another collapsible item on the page (a navbox, sidebar, or table with the collapsible attribute), it is hidden apart from its title bar; if not, it is fully visible.To change this template's initial visibility, the

|state=parameter may be used:{{Paroxetine|state=collapsed}}will show the template collapsed, i.e. hidden apart from its title bar.{{Paroxetine|state=expanded}}will show the template expanded, i.e. fully visible.

Templates using the classes

class=navbox({{navbox}}) orclass=nomobile({{sidebar}}) are not displayed in article space on the mobile web site of English Wikipedia. Mobile page views accounted for 60% to 70% of all page views from 2020 through 2025. Briefly, these templates are not included in articles because 1) they are not well designed for mobile, and 2) they significantly increase page sizes—bad for mobile downloads—in a way that is not useful for the mobile use case. You can review/watch phab:T124168 for further discussion.TemplateData

A navigational box that can be placed at the bottom of articles.

Template parameters[Edit template data]

Parameter Description Type Status State stateThe initial visibility of the navbox

- Suggested values

collapsedexpandedautocollapse

String suggested  In progressPalomares, M. L. D. and Pauly, D., eds. (2011). "{{{1}}} {{{2}}}" in SeaLifeBase. April 2011 version.Turkish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Finnish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2006). "{{{1}}} {{{2}}}" in FishBase. April 2006 version.

In progressPalomares, M. L. D. and Pauly, D., eds. (2011). "{{{1}}} {{{2}}}" in SeaLifeBase. April 2011 version.Turkish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Finnish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2006). "{{{1}}} {{{2}}}" in FishBase. April 2006 version.

|- | ... | — | — | — | — | — | —

|-Old Norse pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Salish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Basque pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]{{{1}}}data-sort-value="" style="background: #ececec; color: #2C2C2C; vertical-align: middle; font-size: smaller; text-align: center; " class="table-na" | UnreleasedNorwegian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}] (aged {{{4}}})Hungarian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Quechua pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Arabic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Punjabi pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Afrikaans pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Romanian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Hebrew pronunciation: [{{{1}}}][INVALID OR MISSING PARAMETER IN TEMPLATE Paroxetine]Uto-Aztecan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Tamil pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Hindustani pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Swedish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Kazakh pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Lao pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Tibetan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Khmer pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]data-sort-value="" style="vertical-align:middle; text-align:center" class="table-na" | —{{{1}}}Welsh pronunciation: [{{{1}}}] Partially doneAthabaskan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Māori pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]IPA: [{{{1}}}]Bulgarian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Korean pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Icelandic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Sanskrit pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Bengali pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Indonesian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Serbo-Croatian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]CROSBI {{{1}}} "Susceptibility of phytoplankton to the increasing presence of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in the aquatic environment: A review". Aquatic Toxicology (Elsevier) 234. May 2021. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2021.105809. PMID 33780670. Bibcode: 2021AqTox.23405809C.

Partially doneAthabaskan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Māori pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]IPA: [{{{1}}}]Bulgarian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Korean pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Icelandic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Sanskrit pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Bengali pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Indonesian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Serbo-Croatian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]CROSBI {{{1}}} "Susceptibility of phytoplankton to the increasing presence of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in the aquatic environment: A review". Aquatic Toxicology (Elsevier) 234. May 2021. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2021.105809. PMID 33780670. Bibcode: 2021AqTox.23405809C.

Slovene pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Thai pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Neukirch, Jürgen; Schmidt, Alexander; Wingberg, Kay (2000), Cohomology of Number Fields, Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften, 323, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-66671-4Template:ScribuntoPersian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]{| class="wikitable" width="100%" This page may be too long to read and navigate comfortably.

This page may be too long to read and navigate comfortably.! rowspan="3" colspan="2" width="14%" style="border-bottom:2px solid grey;" | Date/Time (UTC) ! Configuration ! Serial number ! Launch site ! Outcome |-

|style="text-align:center;background-color:#e3e9e9;" | Payload |style="text-align:center;background-color:#e3e9e9;" | Separation orbit |style="text-align:center;background-color:#e3e9e9;" | Operator |style="text-align:center;background-color:#e3e9e9;" | Function |- | colspan="4" style="text-align:center;background-color:#e4dfdf;border-bottom:2px solid grey;" | Remarks |-

Parameter 1=time required!Hawaiian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]German pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Dutch pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Belarusian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Catalan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]{{{1}}}Mongolian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Javanese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]

This template does not display in the mobile view of Wikipedia; it is desktop only. See Template:Navbox visibility for a brief explanation. This is a navigational template created using {{navbox}}. It can be transcluded on pages by placing

{{Paroxetine}}below the standard article appendices.Initial visibility

This template's initial visibility currently defaults to

autocollapse, meaning that if there is another collapsible item on the page (a navbox, sidebar, or table with the collapsible attribute), it is hidden apart from its title bar; if not, it is fully visible.To change this template's initial visibility, the

|state=parameter may be used:{{Paroxetine|state=collapsed}}will show the template collapsed, i.e. hidden apart from its title bar.{{Paroxetine|state=expanded}}will show the template expanded, i.e. fully visible.

Templates using the classes

class=navbox({{navbox}}) orclass=nomobile({{sidebar}}) are not displayed in article space on the mobile web site of English Wikipedia. Mobile page views accounted for 60% to 70% of all page views from 2020 through 2025. Briefly, these templates are not included in articles because 1) they are not well designed for mobile, and 2) they significantly increase page sizes—bad for mobile downloads—in a way that is not useful for the mobile use case. You can review/watch phab:T124168 for further discussion.TemplateData

A navigational box that can be placed at the bottom of articles.

Template parameters[Edit template data]

Parameter Description Type Status State stateThe initial visibility of the navbox

- Suggested values

collapsedexpandedautocollapse

String suggested Template transclusions

Transclusion maintenance Check completeness of transclusions  Not doneLatin pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]

Not doneLatin pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]

| rowspan="1" colspan="2" style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" |

| style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" | | style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" | | style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" | | style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" |

|-

|-

Vietnamese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Piedmontese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Slovak pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]text-align: auto;Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "{"./Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "{". (age Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "{".–Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "{".)Occitan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]data-sort-value="" style="background: #ececec; color: #2C2C2C; vertical-align: middle; font-size: smaller; text-align: center; " class="table-na" | VariesHejazi pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Spanish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Portuguese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Irish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Mayan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Nahuatl pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Kyrgyz pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Scottish Gaelic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Ukrainian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Burmese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Hindi pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]-4500 —–-4000 —–-3500 —–-3000 —–-2500 —–-2000 —–-1500 —–-1000 —–-500 —–0 — Done

Done To doRussian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Greek pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]

To doRussian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Greek pronunciation: [{{{1}}}] Danish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Northern Sami pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Mandarin pronunciation: [{{{ipa}}}]Cantonese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Entry from Paroxetine from TCI Europe, retrieved on {{{Date}}}Chambers, Robert; Thomson, Thomas Napier (1857). "[[s:A biographical dictionary of eminent Scotsmen/|]]". A Biographical Dictionary of Eminent Scotsmen. Glasgow: Blackie and Son.{{{1}}}Polish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Malagasy pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Japanese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Armenian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Czech pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]∶Manx pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/full/{{{1}}}/0 Alemannic German pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Tagalog pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Egyptian Arabic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]French pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Error: Invalid time.

Danish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Northern Sami pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Mandarin pronunciation: [{{{ipa}}}]Cantonese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Entry from Paroxetine from TCI Europe, retrieved on {{{Date}}}Chambers, Robert; Thomson, Thomas Napier (1857). "[[s:A biographical dictionary of eminent Scotsmen/|]]". A Biographical Dictionary of Eminent Scotsmen. Glasgow: Blackie and Son.{{{1}}}Polish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Malagasy pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Japanese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Armenian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Czech pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]∶Manx pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/full/{{{1}}}/0 Alemannic German pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Tagalog pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Egyptian Arabic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]French pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Error: Invalid time.

This template does not display in the mobile view of Wikipedia; it is desktop only. See Template:Navbox visibility for a brief explanation. This is a navigational template created using {{navbox}}. It can be transcluded on pages by placing

{{Paroxetine}}below the standard article appendices.Initial visibility

This template's initial visibility currently defaults to

autocollapse, meaning that if there is another collapsible item on the page (a navbox, sidebar, or table with the collapsible attribute), it is hidden apart from its title bar; if not, it is fully visible.To change this template's initial visibility, the

|state=parameter may be used:{{Paroxetine|state=collapsed}}will show the template collapsed, i.e. hidden apart from its title bar.{{Paroxetine|state=expanded}}will show the template expanded, i.e. fully visible.

Templates using the classes

class=navbox({{navbox}}) orclass=nomobile({{sidebar}}) are not displayed in article space on the mobile web site of English Wikipedia. Mobile page views accounted for 60% to 70% of all page views from 2020 through 2025. Briefly, these templates are not included in articles because 1) they are not well designed for mobile, and 2) they significantly increase page sizes—bad for mobile downloads—in a way that is not useful for the mobile use case. You can review/watch phab:T124168 for further discussion.TemplateData

A navigational box that can be placed at the bottom of articles.

Template parameters[Edit template data]

Parameter Description Type Status State stateThe initial visibility of the navbox

- Suggested values

collapsedexpandedautocollapse

String suggested  In progressPalomares, M. L. D. and Pauly, D., eds. (2011). "{{{1}}} {{{2}}}" in SeaLifeBase. April 2011 version.Turkish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Finnish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2006). "{{{1}}} {{{2}}}" in FishBase. April 2006 version.

In progressPalomares, M. L. D. and Pauly, D., eds. (2011). "{{{1}}} {{{2}}}" in SeaLifeBase. April 2011 version.Turkish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Finnish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2006). "{{{1}}} {{{2}}}" in FishBase. April 2006 version.

|- | ... | — | — | — | — | — | —

|-Old Norse pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Salish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Basque pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]{{{1}}}data-sort-value="" style="background: #ececec; color: #2C2C2C; vertical-align: middle; font-size: smaller; text-align: center; " class="table-na" | UnreleasedNorwegian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}] (aged {{{4}}})Hungarian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Quechua pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Arabic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Punjabi pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Afrikaans pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Romanian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Hebrew pronunciation: [{{{1}}}][INVALID OR MISSING PARAMETER IN TEMPLATE Paroxetine]Uto-Aztecan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Tamil pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Hindustani pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Swedish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Kazakh pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Lao pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Tibetan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Khmer pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]data-sort-value="" style="vertical-align:middle; text-align:center" class="table-na" | —{{{1}}}Welsh pronunciation: [{{{1}}}] Partially doneAthabaskan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Māori pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]IPA: [{{{1}}}]Bulgarian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Korean pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Icelandic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Sanskrit pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Bengali pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Indonesian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Serbo-Croatian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]CROSBI {{{1}}} "Mixture and single-substance toxicity of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors toward algae and crustaceans". Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (John Wiley & Sons, Inc.) 26 (1): 85–91. January 2007. doi:10.1897/06-219R.1. PMID 17269464. Bibcode: 2007EnvTC..26...85C.

Partially doneAthabaskan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Māori pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]IPA: [{{{1}}}]Bulgarian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Korean pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Icelandic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Sanskrit pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Bengali pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Indonesian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Serbo-Croatian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]CROSBI {{{1}}} "Mixture and single-substance toxicity of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors toward algae and crustaceans". Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (John Wiley & Sons, Inc.) 26 (1): 85–91. January 2007. doi:10.1897/06-219R.1. PMID 17269464. Bibcode: 2007EnvTC..26...85C.

- ↑

Slovene pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Thai pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Neukirch, Jürgen; Schmidt, Alexander; Wingberg, Kay (2000), Cohomology of Number Fields, Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften, 323, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-66671-4Template:ScribuntoPersian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]{| class="wikitable" width="100%" This page may be too long to read and navigate comfortably.

This page may be too long to read and navigate comfortably.! rowspan="3" colspan="2" width="14%" style="border-bottom:2px solid grey;" | Date/Time (UTC) ! Configuration ! Serial number ! Launch site ! Outcome |-

|style="text-align:center;background-color:#e3e9e9;" | Payload |style="text-align:center;background-color:#e3e9e9;" | Separation orbit |style="text-align:center;background-color:#e3e9e9;" | Operator |style="text-align:center;background-color:#e3e9e9;" | Function |- | colspan="4" style="text-align:center;background-color:#e4dfdf;border-bottom:2px solid grey;" | Remarks |-

Parameter 1=time required!Hawaiian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]German pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Dutch pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Belarusian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Catalan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]{{{1}}}Mongolian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Javanese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]

This template does not display in the mobile view of Wikipedia; it is desktop only. See Template:Navbox visibility for a brief explanation. This is a navigational template created using {{navbox}}. It can be transcluded on pages by placing

{{Paroxetine}}below the standard article appendices.Initial visibility

This template's initial visibility currently defaults to

autocollapse, meaning that if there is another collapsible item on the page (a navbox, sidebar, or table with the collapsible attribute), it is hidden apart from its title bar; if not, it is fully visible.To change this template's initial visibility, the

|state=parameter may be used:{{Paroxetine|state=collapsed}}will show the template collapsed, i.e. hidden apart from its title bar.{{Paroxetine|state=expanded}}will show the template expanded, i.e. fully visible.

Templates using the classes

class=navbox({{navbox}}) orclass=nomobile({{sidebar}}) are not displayed in article space on the mobile web site of English Wikipedia. Mobile page views accounted for 60% to 70% of all page views from 2020 through 2025. Briefly, these templates are not included in articles because 1) they are not well designed for mobile, and 2) they significantly increase page sizes—bad for mobile downloads—in a way that is not useful for the mobile use case. You can review/watch phab:T124168 for further discussion.TemplateData

A navigational box that can be placed at the bottom of articles.

Template parameters[Edit template data]

Parameter Description Type Status State stateThe initial visibility of the navbox

- Suggested values

collapsedexpandedautocollapse

String suggested Template transclusions

Transclusion maintenance Check completeness of transclusions  Not doneLatin pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]

Not doneLatin pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]

| rowspan="1" colspan="2" style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" |

| style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" | | style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" | | style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" | | style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" |

|-

|-

Vietnamese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Piedmontese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Slovak pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]text-align: auto;Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "{"./Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "{". (age Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "{".–Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "{".)Occitan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]data-sort-value="" style="background: #ececec; color: #2C2C2C; vertical-align: middle; font-size: smaller; text-align: center; " class="table-na" | VariesHejazi pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Spanish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Portuguese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Irish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Mayan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Nahuatl pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Kyrgyz pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Scottish Gaelic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Ukrainian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Burmese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Hindi pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]-4500 —–-4000 —–-3500 —–-3000 —–-2500 —–-2000 —–-1500 —–-1000 —–-500 —–0 — Done

Done To doRussian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Greek pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]

To doRussian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Greek pronunciation: [{{{1}}}] Danish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Northern Sami pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Mandarin pronunciation: [{{{ipa}}}]Cantonese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Entry from Paroxetine from TCI Europe, retrieved on {{{Date}}}Chambers, Robert; Thomson, Thomas Napier (1857). "[[s:A biographical dictionary of eminent Scotsmen/|]]". A Biographical Dictionary of Eminent Scotsmen. Glasgow: Blackie and Son.{{{1}}}Polish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Malagasy pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Japanese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Armenian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Czech pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]∶Manx pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/full/{{{1}}}/0 Alemannic German pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Tagalog pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Egyptian Arabic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]French pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Error: Invalid time.

Danish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Northern Sami pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Mandarin pronunciation: [{{{ipa}}}]Cantonese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Entry from Paroxetine from TCI Europe, retrieved on {{{Date}}}Chambers, Robert; Thomson, Thomas Napier (1857). "[[s:A biographical dictionary of eminent Scotsmen/|]]". A Biographical Dictionary of Eminent Scotsmen. Glasgow: Blackie and Son.{{{1}}}Polish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Malagasy pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Japanese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Armenian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Czech pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]∶Manx pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/full/{{{1}}}/0 Alemannic German pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Tagalog pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Egyptian Arabic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]French pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Error: Invalid time.

This template does not display in the mobile view of Wikipedia; it is desktop only. See Template:Navbox visibility for a brief explanation. This is a navigational template created using {{navbox}}. It can be transcluded on pages by placing

{{Paroxetine}}below the standard article appendices.Initial visibility

This template's initial visibility currently defaults to

autocollapse, meaning that if there is another collapsible item on the page (a navbox, sidebar, or table with the collapsible attribute), it is hidden apart from its title bar; if not, it is fully visible.To change this template's initial visibility, the

|state=parameter may be used:{{Paroxetine|state=collapsed}}will show the template collapsed, i.e. hidden apart from its title bar.{{Paroxetine|state=expanded}}will show the template expanded, i.e. fully visible.

Templates using the classes

class=navbox({{navbox}}) orclass=nomobile({{sidebar}}) are not displayed in article space on the mobile web site of English Wikipedia. Mobile page views accounted for 60% to 70% of all page views from 2020 through 2025. Briefly, these templates are not included in articles because 1) they are not well designed for mobile, and 2) they significantly increase page sizes—bad for mobile downloads—in a way that is not useful for the mobile use case. You can review/watch phab:T124168 for further discussion.TemplateData

A navigational box that can be placed at the bottom of articles.

Template parameters[Edit template data]

Parameter Description Type Status State stateThe initial visibility of the navbox

- Suggested values

collapsedexpandedautocollapse

String suggested  In progressPalomares, M. L. D. and Pauly, D., eds. (2011). "{{{1}}} {{{2}}}" in SeaLifeBase. April 2011 version.Turkish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Finnish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2006). "{{{1}}} {{{2}}}" in FishBase. April 2006 version.

In progressPalomares, M. L. D. and Pauly, D., eds. (2011). "{{{1}}} {{{2}}}" in SeaLifeBase. April 2011 version.Turkish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Finnish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2006). "{{{1}}} {{{2}}}" in FishBase. April 2006 version.

|- | ... | — | — | — | — | — | —

|-Old Norse pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Salish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Basque pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]{{{1}}}data-sort-value="" style="background: #ececec; color: #2C2C2C; vertical-align: middle; font-size: smaller; text-align: center; " class="table-na" | UnreleasedNorwegian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}] (aged {{{4}}})Hungarian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Quechua pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Arabic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Punjabi pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Afrikaans pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Romanian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Hebrew pronunciation: [{{{1}}}][INVALID OR MISSING PARAMETER IN TEMPLATE Paroxetine]Uto-Aztecan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Tamil pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Hindustani pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Swedish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Kazakh pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Lao pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Tibetan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Khmer pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]data-sort-value="" style="vertical-align:middle; text-align:center" class="table-na" | —{{{1}}}Welsh pronunciation: [{{{1}}}] Partially doneAthabaskan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Māori pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]IPA: [{{{1}}}]Bulgarian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Korean pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Icelandic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Sanskrit pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Bengali pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Indonesian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Serbo-Croatian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]CROSBI {{{1}}} "Breakthroughs in Medicinal Chemistry: New Targets and Mechanisms, New Drugs, New Hopes-3". Molecules (MDPI AG) 23 (7): 1596. June 2018. doi:10.3390/molecules23071596. PMID 29966350.

Partially doneAthabaskan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Māori pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]IPA: [{{{1}}}]Bulgarian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Korean pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Icelandic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Sanskrit pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Bengali pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Indonesian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Serbo-Croatian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]CROSBI {{{1}}} "Breakthroughs in Medicinal Chemistry: New Targets and Mechanisms, New Drugs, New Hopes-3". Molecules (MDPI AG) 23 (7): 1596. June 2018. doi:10.3390/molecules23071596. PMID 29966350.

Slovene pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Thai pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Neukirch, Jürgen; Schmidt, Alexander; Wingberg, Kay (2000), Cohomology of Number Fields, Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften, 323, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-66671-4Template:ScribuntoPersian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]{| class="wikitable" width="100%" This page may be too long to read and navigate comfortably.

This page may be too long to read and navigate comfortably.! rowspan="3" colspan="2" width="14%" style="border-bottom:2px solid grey;" | Date/Time (UTC) ! Configuration ! Serial number ! Launch site ! Outcome |-

|style="text-align:center;background-color:#e3e9e9;" | Payload |style="text-align:center;background-color:#e3e9e9;" | Separation orbit |style="text-align:center;background-color:#e3e9e9;" | Operator |style="text-align:center;background-color:#e3e9e9;" | Function |- | colspan="4" style="text-align:center;background-color:#e4dfdf;border-bottom:2px solid grey;" | Remarks |-

Parameter 1=time required!Hawaiian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]German pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Dutch pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Belarusian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Catalan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]{{{1}}}Mongolian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Javanese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]

This template does not display in the mobile view of Wikipedia; it is desktop only. See Template:Navbox visibility for a brief explanation. This is a navigational template created using {{navbox}}. It can be transcluded on pages by placing

{{Paroxetine}}below the standard article appendices.Initial visibility

This template's initial visibility currently defaults to

autocollapse, meaning that if there is another collapsible item on the page (a navbox, sidebar, or table with the collapsible attribute), it is hidden apart from its title bar; if not, it is fully visible.To change this template's initial visibility, the

|state=parameter may be used:{{Paroxetine|state=collapsed}}will show the template collapsed, i.e. hidden apart from its title bar.{{Paroxetine|state=expanded}}will show the template expanded, i.e. fully visible.

Templates using the classes

class=navbox({{navbox}}) orclass=nomobile({{sidebar}}) are not displayed in article space on the mobile web site of English Wikipedia. Mobile page views accounted for 60% to 70% of all page views from 2020 through 2025. Briefly, these templates are not included in articles because 1) they are not well designed for mobile, and 2) they significantly increase page sizes—bad for mobile downloads—in a way that is not useful for the mobile use case. You can review/watch phab:T124168 for further discussion.TemplateData

A navigational box that can be placed at the bottom of articles.

Template parameters[Edit template data]

Parameter Description Type Status State stateThe initial visibility of the navbox

- Suggested values

collapsedexpandedautocollapse

String suggested Template transclusions

Transclusion maintenance Check completeness of transclusions  Not doneLatin pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]

Not doneLatin pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]

| rowspan="1" colspan="2" style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" |

| style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" | | style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" | | style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" | | style="border-top:2px solid #aabbcc;" |

|-

|-

Vietnamese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Piedmontese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Slovak pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]text-align: auto;Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "{"./Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "{". (age Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "{".–Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "{".)Occitan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]data-sort-value="" style="background: #ececec; color: #2C2C2C; vertical-align: middle; font-size: smaller; text-align: center; " class="table-na" | VariesHejazi pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Spanish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Portuguese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Irish pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Mayan pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Nahuatl pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Kyrgyz pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Scottish Gaelic pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Ukrainian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Burmese pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Hindi pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]-4500 —–-4000 —–-3500 —–-3000 —–-2500 —–-2000 —–-1500 —–-1000 —–-500 —–0 — Done

Done To doRussian pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]Greek pronunciation: [{{{1}}}]