Chemistry:Amoxapine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | A-mox-a-peen[1] |

| Trade names | Asendin, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682202 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | >60%[2] |

| Protein binding | 90%[3] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (cytochrome P450 system)[2] |

| Elimination half-life | 8–10 hours (30 hours for chief active metabolite)[3] |

| Excretion | Renal (60%), feces (18%)[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

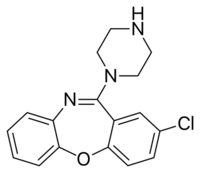

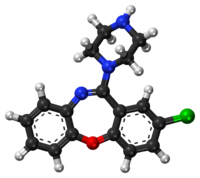

| Formula | C17H16ClN3O |

| Molar mass | 313.79 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Amoxapine, sold under the brand name Asendin among others, is a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA). It is the N-demethylated metabolite of loxapine. Amoxapine first received marketing approval in the United States in 1980, approximately 10 to 20 years after most of the other TCAs were introduced in the United States.[4]

Medical uses

Amoxapine is used in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Compared to other antidepressants it is believed to have a faster onset of action, with therapeutic effects seen within four to seven days.[5][6] In excess of 80% of patients that do respond to amoxapine are reported to respond within two weeks of the beginning of treatment.[7] It also has properties similar to those of the atypical antipsychotics,[8][9][10] and may behave as one[11][12] and thus may be used in the treatment of schizophrenia off-label. Despite its apparent lack of extrapyramidal side effects in patients with schizophrenia it has been found to exacerbate motor symptoms in patients with Parkinson's disease and psychosis.[13]

Contraindications

As with all FDA-approved antidepressants it carries a black-box warning about the potential of an increase in suicidal thoughts or behaviour in children, adolescents and young adults under the age of 25.[2] Its use is also advised against in individuals with known hypersensitivities to either amoxapine or other ingredients in its oral formulations.[2] Its use is also recommended against in the following disease states:[2]

- Severe cardiovascular disorders (potential of cardiotoxic adverse effects such as QT interval prolongation)

- Uncorrected narrow angle glaucoma

- Acute recovery post-myocardial infarction

Its use is also advised against in individuals concurrently on monoamine oxidase inhibitors or if they have been on one in the past 14 days and in individuals on drugs that are known to prolong the QT interval (e.g. ondansetron, citalopram, pimozide, sertindole, ziprasidone, haloperidol, chlorpromazine, thioridazine, etc.).[2]

Lactation

Its use in breastfeeding mothers not recommended as it is excreted in breast milk and the concentration found in breast milk is approximately a quarter that of the maternal serum level.[5][14]

Side effects

Adverse effects by incidence:[2][15]

Note: Serious (that is, those that can either result in permanent injury or are irreversible or are potentially life-threatening) are written in bold text.

Very common (>10% incidence) adverse effects include:

- Constipation

- Dry mouth

- Sedation

Common (1–10% incidence) adverse effects include:

- Anxiety

- Ataxia

- Blurred vision

- Confusion

- Dizziness

- Headache

- Fatigue

- Nausea

- Nervousness/restlessness

- Excessive appetite

- Rash

- Increased perspiration (sweating)

- Tremor

- Palpitations

- Nightmares

- Excitement

- Weakness

- ECG changes

- Oedema. An abnormal accumulation of fluids in the tissues of the body leading to swelling.

- Prolactin levels increased. Prolactin is a hormone that regulates the generation of breast milk. Prolactin elevation is not as significant as with risperidone or haloperidol.

Uncommon/Rare (<1% incidence) adverse effects include:

- Diarrhoea

- Flatulence

- Hypertension (high blood pressure)

- Hypotension (low blood pressure)

- Syncope (fainting)

- Tachycardia (high heart rate)

- Menstrual irregularity

- Disturbance of accommodation

- Mydriasis (pupil dilation)

- Orthostatic hypotension (a drop in blood pressure that occurs upon standing up)

- Seizure

- Urinary retention (being unable to pass urine)

- Urticaria (hives)

- Vomiting

- Nasal congestion

- Photosensitization

- Hypomania (a dangerously elated/irritable mood)

- Tingling

- Paresthesias of the extremities

- Tinnitus

- Disorientation

- Numbness

- Incoordination

- Disturbed concentration

- Epigastric distress

- Peculiar taste in the mouth

- Increased or decreased libido

- Impotence (difficulty achieving an erection)

- Painful ejaculation

- Lacrimation (crying without an emotional cause)

- Weight gain

- Altered liver function

- Breast enlargement

- Drug fever

- Pruritus (itchiness)

- Vasculitis a disorder where blood vessels are destroyed by inflammation. Can be life-threatening if it affects the right blood vessels.

- Galactorrhoea (lactation that is not associated with pregnancy or breast feeding)

- Delayed micturition (that is, delays in urination from when a conscious effort to urinate is made)

- Hyperthermia (elevation of body temperature; its seriousness depends on the extent of the hyperthermia)

- Syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) this is basically when the body's level of the hormone, antidiuretic hormone, which regulates the conservation of water and the restriction of blood vessels, is elevated. This is potentially fatal as it can cause electrolyte abnormalities including hyponatraemia (low blood sodium), hypokalaemia (low blood potassium) and hypocalcaemia (low blood calcium) which can be life-threatening.

- Agranulocytosis a drop in white blood cell counts. The white blood cells are the cells of the immune system that fight off foreign invaders. Hence agranulocytosis leaves an individual open to life-threatening infections.

- Leukopaenia the same as agranulocytosis but less severe.

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (a potentially fatal reaction to antidopaminergic agents, most often antipsychotics. It is characterised by hyperthermia, diarrhoea, tachycardia, mental status changes [e.g. confusion], rigidity, extrapyramidal side effects)

- Tardive dyskinesia a most often irreversible neurologic reaction to antidopaminergic treatment, characterised by involuntary movements of facial muscles, tongue, lips, and other muscles. It develops most often only after prolonged (months, years or even decades) exposure to antidopaminergics.

- Extrapyramidal side effects. Motor symptoms such as tremor, parkinsonism, involuntary movements, reduced ability to move one's voluntary muscles, etc.

Unknown incidence or relationship to drug treatment adverse effects include:

- Paralytic ileus (paralysed bowel)

- Atrial arrhythmias including atrial fibrillation

- Myocardial infarction (heart attack)

- Stroke

- Heart block

- Hallucinations

- Purpura

- Petechiae

- Parotid swelling

- Changes in blood glucose levels

- Pancreatitis swelling of the pancreas

- Hepatitis swelling of the liver

- Urinary frequency

- Testicular swelling

- Anorexia (weight loss)

- Alopecia (hair loss)

- Thrombocytopenia a significant drop in platelet count that leaves one open to life-threatening bleeds.

- Eosinophilia an elevated level of the eosinophils of the body. Eosinophils are the type of immune cell that's job is to fight off parasitic invaders.

- Jaundice yellowing of the skin, eyes and mucous membranes due to an impaired ability of the body to clear the by product of haem breakdown, bilirubin, most often the result of liver damage as it is the liver's responsibility to clear bilirubin.

It tends to produce less anticholinergic effects, sedation and weight gain than some of the earlier TCAs (e.g. amitriptyline, clomipramine, doxepin, imipramine, trimipramine).[16] It may also be less cardiotoxic than its predecessors.[17]

Overdose

It is considered particularly toxic in overdose,[18] with a high rate of renal failure (which usually takes 2–5 days), rhabdomyolysis, coma, seizures and even status epilepticus.[17] Some believe it to be less cardiotoxic than other TCAs in overdose, although reports of cardiotoxic overdoses have been made.[5][15]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | Ki (nM) | Species | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| NET | 16 | Human | [19] |

| DAT | 4,310 | Human | [19] |

| 5-HT2A | 0.5 | Human | [20] |

| 5-HT2C | 2.0 | Monkey | [21] |

| 5-HT6 | 6.0–50 | Human | [21][22] |

| 5-HT7 | 41 | Monkey | [21] |

| α1 | 50 | Human | [23] |

| α2 | 2,600 | Human | [23] |

| D2 | 3.6–160 | Human | [24][20][23] |

| D3 | 11 | Human | [20] |

| D4 | 2.0–40 | Human | [20] |

| H1 | 7.9–25 | Human | [25][23] |

| H2 | ND | ND | ND |

| H3 | >100,000 | Human | [25] |

| H4 | 6,310 | Human | [25] |

| mACh | 1,000 | Human | [23] |

| Values are Ki (nM). The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. | |||

Amoxapine possesses a wide array of pharmacological effects. It is a moderate and strong reuptake inhibitor of serotonin and norepinephrine, respectively,[19] and binds to the 5-HT2A,[26] 5-HT2B,[27] 5-HT2C,[26] 5-HT3,[28] 5-HT6,[21] 5-HT7,[21] D2,[23] α1-adrenergic,[23] D3,[24] D4,[24] and H1 receptors[23] with varying but significant affinity, where it acts as an antagonist (or inverse agonist depending on the receptor in question) at all sites. It has weak but negligible affinity for the dopamine transporter and the 5-HT1A,[28] 5-HT1B,[28] D1,[29] α2-adrenergic,[23] H4,[30] mACh,[23] and GABAA receptors,[29] and no affinity for the β-adrenergic receptors or the allosteric benzodiazepine site on the GABAA receptor.[29] Amoxapine is also a weak GlyT2 blocker,[31] as well as a weak (Ki = 2.5 μM, EC50 = 0.98 μM) δ-opioid receptor partial agonist.[32]

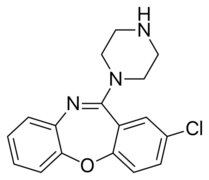

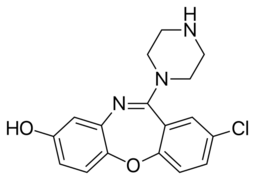

7-Hydroxyamoxapine, a major active metabolite of amoxapine, is a more potent dopamine receptor antagonist and contributes to its neuroleptic efficacy,[8] whereas 8-hydroxyamoxapine is a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor but a stronger serotonin reuptake inhibitor and helps to balance amoxapine's ratio of serotonin to norepinephrine transporter blockade.[33]

Pharmacokinetics

Amoxapine is metabolised into two main active metabolites: 7-hydroxyamoxapine and 8-hydroxyamoxapine.[34]

|

x180px|7-hydroxyamoxapine |  |

| Compound[34][35][36] | t1/2 (hr)[37] | tmax (hr) | CSS (ng/mL) | Protein binding[2] | Vd[2] | Excretion[2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amoxapine | 8 | 1-2 | 17-93 ng/mL (divided dosing), 13-209 ng/mL (single daily dosing) | 90% | 0.9-1.2 L/kg | Urine (60%), feces (18%) |

| 8-hydroxyamoxapine | 30 | 5.3 (single dosing) | 158-512 ng/mL (divided dosing), 143-593 ng/mL (single dose) | ? | ? | ? |

| 7-hydroxyamoxapine | 6.5 | 2.6-5.4 (single dosing) | ? | ? | ? | ? |

Where:

- t1/2 is the elimination half life of the compound.

- tmax is the time to peak plasma levels after oral administration of amoxapine.

- CSS is the steady state plasma concentration.

- protein binding is the extent of plasma protein binding.

- Vd is the volume of distribution of the compound.

Society and culture

Brand names

Brand names for amoxapine include (where † denotes discontinued brands):[5][38]

- Adisen (South Korea )

- Amolife (India )

- Amoxan (Japan )

- Asendin† (previously marketed in Canada , NZ, United States of America )

- Asendis† (previously marketed in IE, United Kingdom )

- Défanyl (France )

- Demolox (Denmark †, India , Spain †)

- Oxamine (India )

- Oxcap (India )

See also

References

- ↑ "Amoxapine: Indications, Side Effects, Warnings -Drugs.com". Drugs.com. 6 November 2013. https://www.drugs.com/cdi/amoxapine.html.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 "Asendin, (amoxapine) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. http://reference.medscape.com/drug/amoxapine-342937#showall.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Evaluation of amoxapine". Clinical Pharmacy 1 (5): 417–424. September–October 1982. PMID 6764165.

- ↑ National Center for Drugs and Biologics (U.S.) (1984). Approved Prescription Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations (5th, Cumulative Supplement 3 ed.). Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Food and Drug Administration. p. IV-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=qARg2DWrVawC&pg=PAIV-9&dq=asendin.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Amoxapine. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. 30 January 2013. https://www.medicinescomplete.com/mc/martindale/current/2503-q.htm. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ "Systematic studies with amoxapine, a new antidepressant". International Pharmacopsychiatry 17 (1): 18–27. 1982. doi:10.1159/000468553. PMID 7045016.

- ↑ Product Information: Asendin(R), amoxapine tablets. Physicians' Desk Reference (electronic version), MICROMEDEX, Inc, Englewood, CO, USA, 1999.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Amoxapine: neuroleptic as well as antidepressant?". The American Journal of Psychiatry 139 (9): 1165–1167. September 1982. doi:10.1176/ajp.139.9.1165. PMID 6126130.

- ↑ "Is amoxapine an atypical antipsychotic? Positron-emission tomography investigation of its dopamine2 and serotonin2 occupancy". Biological Psychiatry 45 (9): 1217–1220. May 1999. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(98)00204-2. PMID 10331115.

- ↑ "Antipsychoticlike effects of amoxapine, without catalepsy, using the prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle reflex test in rats". Biological Psychiatry 47 (7): 670–676. April 2000. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00267-X. PMID 10745061.

- ↑ "Amoxapine as an atypical antipsychotic: a comparative study vs risperidone". Neuropsychopharmacology 30 (12): 2236–2244. December 2005. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300796. PMID 15956984.

- ↑ "Amoxapine as an antipsychotic: comparative study versus haloperidol". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 27 (6): 575–581. December 2007. doi:10.1097/jcp.0b013e31815a4424. PMID 18004123.

- ↑ "Amoxapine shows an antipsychotic effect but worsens motor function in patients with Parkinson's disease and psychosis". Clinical Neuropharmacology 24 (4): 242–244. July–August 2001. doi:10.1097/00002826-200107000-00010. PMID 11479398.

- ↑ "Galactorrhea and hyperprolactinemia associated with amoxapine therapy. Report of a case". JAMA 242 (17): 1900–1901. October 1979. doi:10.1001/jama.1979.03300170046029. PMID 573343.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "AMOXAPINE TABLET [WATSON LABORATORIES, INC."]. DailyMed. Watson Laboratories, Inc.. July 2010. http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=a16297df-3158-48db-85e5-5cd506885556.

- ↑ "Side effects of antidepressant medications". UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer Health. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/image?imageKey=PC%2F62488&source=image_view&view=print&topicKey=PSYCH/85816&source=see_link&elapsedTimeMs=2.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics (4th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. 2007. ISBN 978-0-7020-4293-5.

- ↑ "Suicidal antidepressant overdoses: a comparative analysis by antidepressant type". Journal of Medical Toxicology 4 (4): 238–250. December 2008. doi:10.1007/BF03161207. PMID 19031375.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedpmid9537821 - ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 "Antipsychotic drugs which elicit little or no parkinsonism bind more loosely than dopamine to brain D2 receptors, yet occupy high levels of these receptors". Molecular Psychiatry 3 (2): 123–134. March 1998. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4000336. PMID 9577836.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 "Binding of typical and atypical antipsychotic agents to 5-hydroxytryptamine-6 and 5-hydroxytryptamine-7 receptors". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 268 (3): 1403–1410. March 1994. PMID 7908055.

- ↑ "Cloning, characterization, and chromosomal localization of a human 5-HT6 serotonin receptor". Journal of Neurochemistry 66 (1): 47–56. January 1996. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66010047.x. PMID 8522988.

- ↑ 23.00 23.01 23.02 23.03 23.04 23.05 23.06 23.07 23.08 23.09 "Antagonism by antidepressants of neurotransmitter receptors of normal human brain in vitro". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 230 (1): 94–102. July 1984. PMID 6086881.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 "Intrinsic efficacy of antipsychotics at human D2, D3, and D4 dopamine receptors: identification of the clozapine metabolite N-desmethylclozapine as a D2/D3 partial agonist". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 315 (3): 1278–1287. December 2005. doi:10.1124/jpet.105.092155. PMID 16135699.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 "Interactions of recombinant human histamine H₁R, H₂R, H₃R, and H₄R receptors with 34 antidepressants and antipsychotics". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology 385 (2): 145–170. February 2012. doi:10.1007/s00210-011-0704-0. PMID 22033803.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "Interactions of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with the serotonin 5-HT2c receptor". Psychopharmacology 126 (3): 234–240. August 1996. doi:10.1007/BF02246453. PMID 8876023.

- ↑ "Further evidence that 5-HT-induced relaxation of pig pulmonary artery is mediated by endothelial 5-HT(2B) receptors". British Journal of Pharmacology 130 (3): 692–698. June 2000. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0703341. PMID 10821800.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 "[Preclinical pharmacology of amoxapine and amitriptyline. Implications of serotoninergic and opiodergic systems in their central effect in rats]" (in fr). L'Encéphale 17 Spec No 3: 415–422. December 1991. PMID 1666997.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 "[Comparison of the affinities of amoxapine and loxapine for various receptors in rat brain and the receptor down-regulation after chronic administration]" (in zh). Yao Xue Xue Bao = Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica 25 (12): 881–885. 1990. PMID 1966571.

- ↑ "Evaluation of histamine H1-, H2-, and H3-receptor ligands at the human histamine H4 receptor: identification of 4-methylhistamine as the first potent and selective H4 receptor agonist". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 314 (3): 1310–1321. September 2005. doi:10.1124/jpet.105.087965. PMID 15947036.

- ↑ Neurotransmitter Transporters. Springer Science & Business Media. 2 August 2006. pp. 472–. ISBN 978-3-540-29784-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=CeZDAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA472.

- ↑ "Direct agonist activity of tricyclic antidepressants at distinct opioid receptor subtypes". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 332 (1): 255–265. January 2010. doi:10.1124/jpet.109.159939. PMID 19828880.

- ↑ "The role of metabolites in a bioequivalence study II: amoxapine, 7-hydroxyamoxapine, and 8-hydroxyamoxapine". International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 37 (9): 428–438. September 1999. PMID 10507241.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "Amoxapine: a review of its pharmacology and efficacy in depressed states". Drugs 24 (1): 1–23. July 1982. doi:10.2165/00003495-198224010-00001. PMID 7049659.

- ↑ "Pharmacokinetics of amoxapine and its active metabolites". International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, Therapy, and Toxicology 23 (4): 180–185. April 1985. PMID 3997304.

- ↑ "Pharmacokinetics of amoxapine and its active metabolites in healthy subjects". Current Therapeutic Research 53 (4): 427–434. April 1993. doi:10.1016/S0011-393X(05)80202-4.

- ↑ "Amoxapine Monograph for Professionals - Drugs.com". Drugs.com. Bethesda, MD, USA: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc.. 1 October 2007. https://www.drugs.com/monograph/amoxapine.html.

- ↑ "Amoxapine -Drugs.com". Drugs.com. 2013. https://www.drugs.com/international/amoxapine.html.

|