Chemistry:Butriptyline

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Evadyne, others |

| Other names | AY-62014[1] |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ?[2] |

| Protein binding | >90%[2] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (N-demethylation) |

| Metabolites | Norbutriptyline[2] |

| Elimination half-life | 20 hours[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII |

|

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H27N |

| Molar mass | 293.454 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| |

| |

| | |

Butriptyline, sold under the brand name Evadyne among others, is a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) that has been used in the United Kingdom and several other European countries for the treatment of depression but appears to no longer be marketed.[1][3][4][5][6] Along with trimipramine, iprindole, and amoxapine, it has been described as an "atypical" or "second-generation" TCA due to its relatively late introduction and atypical pharmacology.[7][8] It was very little-used compared to other TCAs, with the number of prescriptions dispensed only in the thousands.[9]

Medical uses

Butriptyline was used in the treatment of depression.[10] It was usually used at dosages of 150–300 mg/day.[11]

Side effects

Butriptyline is closely related to amitriptyline, and produces similar effects as other TCAs, but its side effects like sedation are said to be reduced in severity and it has a lower risk of interactions with other medications.[5][6][9]

Butriptyline has potent antihistamine effects, resulting in sedation and somnolence.[12] It also has potent anticholinergic effects,[13] resulting in side effects like dry mouth, constipation, urinary retention, blurred vision, and cognitive/memory impairment.[12] The drug has relatively weak effects as an alpha-1 blocker and has no effects as a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor,[14][15] so is associated with little to no antiadrenergic and adrenergic side effects.[14][13][additional citation(s) needed]

Overdose

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | Ki (nM) | Species | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| NET | 5,100 990 1,700 (IC50) |

Human Rat Rat |

[15] [16] [17] |

| DAT | 3,940 2,800 5,200 (IC50) |

Human Rat Rat |

[15] [16] [17] |

| 5-HT1A | 7,000 | Human | [18] |

| 5-HT2A | 380 | Human | [18] |

| 5-HT2C | ND | ND | ND |

| α1 | 570 | Human | [14] |

| α2 | 4,800 | Human | [14] |

| D2 | ND | ND | ND |

| H1 | 1.1 | Human | [14] |

| mACh | 35 | Human | [14] |

| Values are Ki (nM), unless otherwise noted. The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. | |||

In vitro, butriptyline is a strong antihistamine and anticholinergic, moderate 5-HT2 and α1-adrenergic receptor antagonist, and very weak or negligible monoamine reuptake inhibitor.[14][18][15][17] These actions appear to confer a profile similar to that of iprindole and trimipramine with serotonin-blocking effects as the apparent predominant mediator of mood-lifting efficacy.[19][17][16]

However, in small clinical trials, using similar doses, butriptyline was found to be similarly effective to amitriptyline and imipramine as an antidepressant, despite the fact that both of these TCAs are far stronger as both 5-HT2 antagonists and serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.[14][18][20] As a result, it may be that butriptyline has a different mechanism of action, or perhaps functions as a prodrug in the body to a metabolite with different pharmacodynamics.

Pharmacokinetics

Therapeutic concentrations of butriptyline are in the range of 60–280 ng/mL (204–954 nmol/L).[21] Its plasma protein binding is greater than 90%.[2]

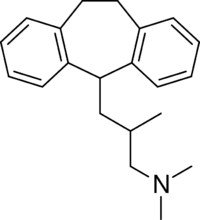

Chemistry

Butriptyline is a tricyclic compound, specifically a dibenzocycloheptadiene, and possesses three rings fused together with a side chain attached in its chemical structure.[22] Other dibenzocycloheptadiene TCAs include amitriptyline, nortriptyline, and protriptyline.[22] Butriptyline is an analogue of amitriptyline with an isobutyl side chain instead of a propylidene side chain.[9][23] It is a tertiary amine TCA, with its side chain-demethylated metabolite norbutriptyline being a secondary amine.[24][25] Other tertiary amine TCAs include amitriptyline, imipramine, clomipramine, dosulepin (dothiepin), doxepin, and trimipramine.[26][27] The chemical name of butriptyline is 3-(10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[a,d]cycloheptene-5-yl)-N,N,2-trimethylpropan-1-amine and its free base form has a chemical formula of C21H27N with a molecular weight of 293.446 g/mol.[1] The drug has been used commercially both as the free base and as the hydrochloride salt.[1][3] The CAS Registry Number of the free base is 15686-37-0 and of the hydrochloride is 5585-73-9.[1][3]

History

Butriptyline was developed by Wyeth and introduced in the United Kingdom in either 1974 or 1975.[4][28][29]

Society and culture

Generic names

Butriptyline is the English and French generic name of the drug and its INN, BAN, and DCF, while butriptyline hydrochloride is its BANM and USAN.[1][3][10] Its generic name in Latin is butriptylinum, in German is butriptylin, and in Spanish is butriptylina.[3]

Brand names

Butriptyline has been marketed under the brand names Evadene, Evadyne, Evasidol, and Centrolese.[1][3][4]

Availability

Butriptyline has been marketed in Europe, including in the United Kingdom , Belgium, Luxembourg, Austria, and Italy.[3][4]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. 14 November 2014. pp. 201–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=0vXTBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA201.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "Dibenzazepines and Related Tricyclic Compounds". Lead Optimization for Medicinal Chemists: Pharmacokinetic Properties of Functional Groups and Organic Compounds. John Wiley & Sons. 4 February 2013. pp. 313–. ISBN 978-3-527-64565-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=YTeY9ZEfNccC&pg=PA313.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Swiss Pharmaceutical Society (2000). Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory (Book with CD-ROM). Boca Raton: Medpharm Scientific Publishers. ISBN 3-88763-075-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=5GpcTQD_L2oC&pg=PA154.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 William Andrew Publishing (22 October 2013). Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia. Elsevier. pp. 777–. ISBN 978-0-8155-1856-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=_J2ti4EkYpkC&pg=PA777.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Tricyclic and tetracyclic antidepressants". Antidepressants, Antipsychotics, Anxiolytics: From Chemistry and Pharmacology to Clinical Application. Wiley. 16 April 2007. pp. 180–. ISBN 978-3-527-31058-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=yXD4QA-Y_Z0C&pg=PA180.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Handbook of Affective Disorders. Guilford Press. 1992. pp. 339–. ISBN 978-0-89862-674-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=r003DuAeZhIC&pg=PA339.

- ↑ "Drug Therapy of Affective Disorders". Textbook Of Pharmacology. Elsevier India. 18 November 2009. pp. 119–. ISBN 978-81-312-1158-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=51ozlZRBvQwC&pg=PA119.

- ↑ "Central Nervous System". Pharmacology (2nd ed.). Elsevier India. 2003. pp. 292–. ISBN 978-81-8147-009-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=X3cCZQCrrjcC&pg=PA292.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Meyler's Side Effects of Psychiatric Drugs. Elsevier. 2009. pp. 7, 18, 31. ISBN 978-0-444-53266-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=s0XYvuPVgaAC&pg=PA31.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. 6 December 2012. pp. 58–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=tsjrCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA58.

- ↑ "Treatment for Affective Disorders". Handbook of Psychiatry: Volume 3, Psychoses of Uncertain Aetiology. CUP Archive. 29 October 1982. pp. 167–. ISBN 978-0-521-28438-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=QFI4AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA167.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Tricyclic antidepressant pharmacology and therapeutic drug interactions updated". British Journal of Pharmacology 151 (6): 737–748. July 2007. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707253. PMID 17471183.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Reactions to Antidepressant Drugs and Lithium Salts". Treatment of Chronic Pain: Possibilities, Limitations, and Long-term Follow-up. CRC Press. 1990. pp. 114–. ISBN 978-3-7186-5027-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=8hHT8OlF3QMC&pg=PA114.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 "Antagonism by antidepressants of neurotransmitter receptors of normal human brain in vitro". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 230 (1): 94–102. July 1984. PMID 6086881.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedpmid9537821 - ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 "Blockade by antidepressants and related compounds of biogenic amine uptake into rat brain synaptosomes: most antidepressants selectively block norepinephrine uptake". European Journal of Pharmacology 104 (3–4): 277–286. September 1984. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(84)90403-5. PMID 6499924.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 "Uptake inhibition of biogenic amines by newer antidepressant drugs: relevance to the dopamine hypothesis of depression". Psychopharmacology 53 (3): 309–314. August 1977. doi:10.1007/BF00492370. PMID 408861.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 "Antagonism by antidepressants of serotonin S1 and S2 receptors of normal human brain in vitro". European Journal of Pharmacology 132 (2–3): 115–121. December 1986. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(86)90596-0. PMID 3816971.

- ↑ "Comparative pharmacological studies on butriptyline and some related standard tricyclic antidepressants". Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology 53 (1): 104–112. February 1975. doi:10.1139/y75-014. PMID 166748.

- ↑ "Tricyclic Antidepressants". Drugs in Psychiatric Practice. Elsevier. 22 October 2013. pp. 194–. ISBN 978-1-4831-9193-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=6gglBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA194.

- ↑ "Radioimmunoassay of Drugs in Body Fluids in a Forensic Context". Forensic Science Progress. Springer Science & Business Media. 6 December 2012. pp. 24–. ISBN 978-3-642-73058-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=JRzrCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA24.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "Appendix 2: List of Pyschotropic Medications". Polypharmacy in Psychiatry Practice, Volume I: Multiple Medication Use Strategies. Springer Science & Business Media. 15 February 2013. pp. 270–271. ISBN 978-94-007-5805-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=jy-LMZU7338C&pg=PA270.

- ↑ "Drug Design and Relationship of Functional Groups to Pharmacological Activity". Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 24 January 2012. pp. 604–. ISBN 978-1-60913-345-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=Sd6ot9ul-bUC&pg=PA604.

- ↑ "Pharmacodynamics of Antidepressants". Pharmacodynamics and Drug Development: Perspectives in Clinical Pharmacology. John Wiley & Sons. 20 September 1994. pp. 160–. ISBN 978-0-471-95052-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=ncRXa8Dq88QC&pg=PA160.

- ↑ "Central Nervous System Drugs". Metabolism of Drugs and Other Xenobiotics. John Wiley & Sons. 23 February 2012. pp. 302–. ISBN 978-3-527-64632-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=f-XHh17NfwgC&pg=PA302.

- ↑ "Drugs Used in the Therapy of Depression". Pharmacology Secrets. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2002. pp. 39–. ISBN 1-56053-470-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=_QQsj3PAUrEC&pg=PA39.

- ↑ "Drugs and Other Physical Treatments". Shorter Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. OUP Oxford. 9 August 2012. pp. 532–. ISBN 978-0-19-162675-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=Y1DtSGq-LnoC&pg=PA532.

- ↑ "Side-effects of tricyclic and related antidepressants". Antidepressants for Elderly People. Springer. 11 November 2013. pp. 182–. ISBN 978-1-4899-3436-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=JVn0BwAAQBAJ&pg=PA182.

- ↑ "Cyclic Antidepressant Drugs". Medical Toxicology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2004. pp. 836–. ISBN 978-0-7817-2845-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=BfdighlyGiwC&pg=PA836.

|