Chemistry:Flupentixol

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Depixol, Fluanxol |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, IM (including a depot) |

| Drug class | Typical antipsychotic |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 40–55% (oral)[1] |

| Metabolism | Gut wall, hepatic[3] |

| Elimination half-life | 35 hours[1] |

| Excretion | Renal (negligible)[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

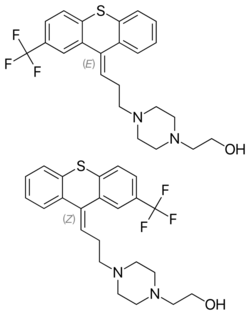

| Formula | C23H25F3N2OS |

| Molar mass | 434.52 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Flupentixol (INN), also known as flupenthixol (former BAN), marketed under brand names such as Depixol and Fluanxol is a typical antipsychotic drug of the thioxanthene class. It was introduced in 1965 by Lundbeck. In addition to single drug preparations, it is also available as flupentixol/melitracen—a combination product containing both melitracen (a tricyclic antidepressant) and flupentixol (marketed as Deanxit). Flupentixol is not approved for use in the United States. It is, however, approved for use in the United Kingdom ,[4] Australia ,[5] Canada , Russian Federation,[6] South Africa , New Zealand, Philippines , Iran, Germany , and various other countries.

Medical uses

Flupentixol's main use is as a long-acting injection given once in every two or three weeks to individuals with schizophrenia who have poor compliance with medication and have frequent relapses of illness, though it is also commonly given as a tablet. There is little formal evidence to support its use for this indication but it has been in use for over fifty years.[4][7]

Flupentixol is also used in low doses as an antidepressant.[4][8][9][10][11][12][13] There is tentative evidence that it reduces the rate of deliberate self-harm, among those who self-harm repeatedly.[14]

Adverse effects

Adverse effect incidence[1][4][5][15][16]

- Common (>1% incidence) adverse effects include

- Extrapyramidal side effects such as: (which usually become apparent soon after therapy is begun or soon after an increase in dose is made)

- Muscle rigidity

- Hypokinesia

- Hyperkinesia

- Parkinsonism

- Tremor

- Akathisia

- Dystonia

- Dry mouth

- Constipation

- Hypersalivation – excessive salivation

- Blurred vision

- Diaphoresis – excessive sweating

- Nausea

- Dizziness

- Somnolence

- Restlessness

- Insomnia

- Overactivity

- Headache

- Nervousness

- Fatigue

- Myalgia

- Hyperprolactinemia and its complications such as: (acutely)

- Sexual dysfunction

- Amenorrhea – cessation of menstrual cycles

- Gynecomastia – enlargement of breast tissue in males

- Galactorrhea – the expulsion of breast milk that's not related to breastfeeding or pregnancy

- and if the hyperprolactinemia persists chronically, the following adverse effects may be seen:

- Reduced bone mineral density leading to osteoporosis (brittle bones)

- Infertility

- Dyspepsia – indigestion

- Abdominal pain

- Flatulence

- Nasal congestion

- Polyuria – passing more urine than usual

- Uncommon (0.1–1% incidence) adverse effects include

- Fainting

- Palpitations

- Rare (<0.1% incidence) adverse effects include

- Blood dyscrasias (abnormalities in the cell composition of blood), such as:

- Agranulocytosis – a drop in white blood cell counts that leaves one open to potentially life-threatening infections

- Neutropenia – a drop in the number of neutrophils (white blood cells that specifically fight bacteria) in one's blood

- Leucopenia – a less severe drop in white blood cell counts than agranulocytosis

- Thrombocytopenia – a drop in the number of platelets in the blood. Platelets are responsible for blood clotting and hence this leads to an increased risk of bruising and other bleeds

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome – a potentially fatal condition that appear to result from central D2 receptor blockade. The symptoms include:

- Hyperthermia

- Muscle rigidity

- Rhabdomyolysis

- Autonomic instability (e.g., tachycardia, diarrhea, diaphoresis, etc.)

- Mental status changes (e.g., coma, agitation, anxiety, confusion, etc.)

- Unknown incidence adverse effects include

- Jaundice

- Abnormal liver function test results

- Tardive dyskinesia – an often incurable movement disorder that usually results from years of continuous treatment with antipsychotic drugs, especially typical antipsychotics like flupenthixol. It presents with repetitive, involuntary, purposeless and slow movements; TD can be triggered by a fast dose reduction in any antipsychotic.

- Hypotension

- Confusional state

- Seizures

- Mania

- Hypomania

- Depression

- Hot flush

- Anergia

- Appetite changes

- Weight changes

- Hyperglycemia – high blood glucose (sugar) levels

- Abnormal glucose tolerance

- Pruritus – itchiness

- Rash

- Dermatitis

- Photosensitivity – sensitivity to light

- Oculogyric crisis

- Accommodation disorder

- Sleep disorder

- Impaired concentration

- Tachycardia

- QTc interval prolongation – an abnormality in the electrical activity of the heart that can lead to potentially fatal changes in heart rhythm (only in overdose or <10 ms increases in QTc)[17][18]

- Torsades de pointes

- Miosis – constriction of the pupil of the eye

- Paralytic ileus – paralysis of the bowel muscles leading to severe constipation, inability to pass wind, etc.

- Mydriasis

- Glaucoma

Interactions

It should not be used concomitantly with medications known to prolong the QTc interval (e.g., 5-HT3 antagonists, tricyclic antidepressants, citalopram, etc.) as this may lead to an increased risk of QTc interval prolongation.[16][1] Neither should it be given concurrently with lithium (medication) as it may increase the risk of lithium toxicity and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.[4][5][16] It should not be given concurrently with other antipsychotics due to the potential for this to increase the risk of side effects, especially neurological side effects such as neuroleptic malignant syndrome.[4][5][16] It should be avoided in patients on CNS depressants such as opioids, alcohol and barbiturates.[16]

Contraindications

It should not be given in the following disease states:[1][4][5][16]

- Pheochromocytoma

- Prolactin-dependent tumors such as pituitary prolactinomas and breast cancer

- Long QT syndrome

- Coma

- Circulatory collapse

- Subcortical brain damage

- Blood dyscrasia

- Parkinson's disease

- Dementia with Lewy bodies

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Binding profile[19]

| Protein | cis-flupentixol | trans-flupentixol |

|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | 8028 | — |

| 5-HT2A | 87.5 (HFC) | — |

| 5-HT2C | 102.2 (RC) | — |

| mAChRs[20] | Neg. | Neg. |

| D1 | 3.5 | 474 (MB) |

| D2 | 0.35 | 120 |

| D3 | 1.75 | 162.5 |

| D4 | 66.3 | >1000 |

| H1 | 0.86 | 5.73 |

Acronyms used:

HFC – Human frontal cortex receptor

MB – Mouse brain receptor

RC – Cloned rat receptor

A study measuring the in vivo receptor occupancies of 13 schizophrenic patients treated with 5.7 ± 1.4 mg/day of flupentixol found 50-70% receptor occupancy for D2, 20 ± 5% for D1, and 20 ± 10% for 5-HT2A.[21]

Its antipsychotic effects are predominantly a function of D2 antagonism.

Its antidepressant effects at lower doses are not well understood; however, it may be mediated by functional selectivity and/or preferentially binding to D2 autoreceptors at low doses, resulting in increased postsynaptic activation via higher dopamine levels. Flupentixol's demonstrated ability to raise dopamine levels in mice[22] and flies[23] lends credibility to the supposition of autoreceptor bias. Functional selectivity may be responsible through causing preferential autoreceptor binding or other means. The effective dosage guideline for an antipsychotic is very closely related to its receptor residency time (i.e., where drugs like aripiprazole take several minutes or more to disassociate from a receptor while drugs like quetiapine and clozapine—with guideline dosages in the hundreds of milligrams—take under 30s)[24][25][26] and long receptor residency time is strongly correlated with likehood of pronounced functional selectivity;[27] thus, with a maximum guideline dose of only 18 mg/day for schizophrenia, there is a significant possibility of this drug possessing unique signalling characteristics that permit counterintuitive dopaminergic action at low doses.

Pharmacokinetics

History

In March 1963 the Danish pharmaceutical company Lundbeck began research into further agents for schizophrenia, having already developed the thioxanthene derivatives clopenthixol and chlorprothixene. By 1965 the promising agent flupenthixol had been developed and trialled in two hospitals in Vienna by Austrian psychiatrist Heinrich Gross.[28] The long- acting decanoate preparation was synthesised in 1967 and introduced into hospital practice in Sweden in 1968, with a reduction in relapses among patients who were put on the depot.[29]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 "Depixol Tablets 3mg - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. Lundbeck Ltd. 27 December 2012. http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/1076/SPC/Depixol+Tablets+3mg/.

- ↑ "Antipsychotic drugs. Clinical pharmacokinetics of potential candidates for plasma concentration monitoring". Clinical Pharmacokinetics 13 (2): 65–90. August 1987. doi:10.2165/00003088-198713020-00001. PMID 2887326.

- ↑ "Clinical pharmacokinetics of the depot antipsychotics". Clinical Pharmacokinetics 10 (4): 315–333. July–August 1985. doi:10.2165/00003088-198510040-00003. PMID 2864156.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Joint Formulary Committee (2013). British National Formulary (BNF) (65 ed.). London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85711-084-8. https://archive.org/details/bnf65britishnati0000unse.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Rossi, S, ed (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- ↑ "Fluanxol® (flupentixol) Tablets Registration Certificate". Russian State Register of Medicinal Products. http://grls.rosminzdrav.ru/Grls_View.aspx?idReg=5644&isOld=1&t=.

- ↑ Shen, Xiaohong, ed (November 2012). "Flupenthixol versus placebo for schizophrenia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 11: CD009777. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009777.pub2. PMID 23152280.

- ↑ "The antidepressant action of flupenthixol". The Practitioner 225 (1355): 761–763. May 1981. PMID 7291129.

- ↑ "Depression-inducing and antidepressive effects of neuroleptics. Experiences with flupenthixol and flupenthixol decanoate". Neuropsychobiology 10 (2–3): 131–136. 1983. doi:10.1159/000117999. PMID 6674820.

- ↑ "A double-blind comparison of flupenthixol, nortriptyline and diazepam in neurotic depression". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 59 (1): 1–8. January 1979. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1979.tb06940.x. PMID 369298.

- ↑ "A controlled comparison of flupenthixol and amitriptyline in depressed outpatients". British Medical Journal 1 (6018): 1116–1118. May 1976. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.6018.1116. PMID 773506.

- ↑ "Effect of flupenthixol on depression with special reference to combination use with tricyclic antidepressants. An uncontrolled pilot study with 45 patients". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 54 (2): 99–105. August 1976. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1976.tb00101.x. PMID 961463.

- ↑ "A controlled comparison of flupenthixol decanoate injections and oral amitriptyline in depressed out-patients". The British Journal of Psychiatry 140 (3): 287–291. March 1982. doi:10.1192/bjp.140.3.287. PMID 7093597.

- ↑ "Pharmacological interventions for self-harm in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015 (7): CD011777. July 2015. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011777. PMID 26147958.

- ↑ "Antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia". Pharmacotherapy 29 (1): 64–73. January 2009. doi:10.1592/phco.29.1.64. PMID 19113797.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 "FLUANXOL® DEPOT FLUANXOL® CONCENTRATED DEPOT". TGA eBusiness Services. Lundbeck Australia Pty Ltd. 28 June 2013. https://www.ebs.tga.gov.au/ebs/picmi/picmirepository.nsf/pdf?OpenAgent&id=CP-2010-PI-05706-3.

- ↑ "Guidelines for the Management of QTc Prolongation in Adults Prescribed Antipsychotics". https://www.england.nhs.uk/north/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2018/12/QTc-flow-diagram-with-medications-final-Dec-17-A3-with-logos.pdf.

- ↑ "British Heart Rhythm Society Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Patients Developing QT Prolongation on Antipsychotic Medication". Arrhythmia & Electrophysiology Review 8 (3): 161–165. July 2019. doi:10.15420/aer.2019.8.3.G1. PMID 31463053.

- ↑ "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. 12 January 2011. http://pdsp.med.unc.edu/pdsp.php.

- ↑ "The binding of some antidepressant drugs to brain muscarinic acetylcholine receptors". British Journal of Pharmacology 68 (3): 541–549. March 1980. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1980.tb14570.x. PMID 7052344.

- ↑ "Occupancy of dopamine D(1), D (2) and serotonin (2A) receptors in schizophrenic patients treated with flupentixol in comparison with risperidone and haloperidol". Psychopharmacology 190 (2): 241–249. February 2007. doi:10.1007/s00213-006-0611-0. PMID 17111172.

- ↑ "Changes in dopamine synthesis rate in the supersensitivity phase after treatment with a single dose of neuroleptics". Psychopharmacology 51 (2): 205–207. January 1977. doi:10.1007/BF00431742. PMID 14353.

- ↑ "Drosophila Dopamine2-like receptors function as autoreceptors". ACS Chemical Neuroscience 2 (12): 723–729. December 2011. doi:10.1021/cn200057k. PMID 22308204.

- ↑ "Does fast dissociation from the dopamine d(2) receptor explain the action of atypical antipsychotics?: A new hypothesis". The American Journal of Psychiatry 158 (3): 360–369. March 2001. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.360. PMID 11229973.

- ↑ "Antipsychotic agents differ in how fast they come off the dopamine D2 receptors. Implications for atypical antipsychotic action". Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience 25 (2): 161–166. March 2000. PMID 10740989.

- ↑ "Slow dissociation of partial agonists from the D₂ receptor is linked to reduced prolactin release". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 15 (5): 645–656. June 2012. doi:10.1017/S1461145711000824. PMID 21733233.

- ↑ "The role of kinetic context in apparent biased agonism at GPCRs". Nature Communications 7: 10842. February 2016. doi:10.1038/ncomms10842. PMID 26905976. Bibcode: 2016NatCo...710842K.

- ↑ "Flupenthixol (Fluanxol®), ein Neues Neuroleptikum aus der Thiaxanthenreihe (Klinische Erfahrungen bei Einem Psychiatrischen Krankengut)". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 41: 42–56. 1965. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1965.tb04969.x.

- ↑ "Flupenthixol decanoate--in treatment of out-patients". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum 255: 15–24. 1974. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1974.tb08890.x. PMID 4533707.

|