Chemistry:Cyproheptadine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌsaɪproʊˈhɛptədiːn/[1] |

| Trade names | Periactin, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682541 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 96 to 99% |

| Metabolism | Liver,[3][4] mostly CYP3A4 mediated. |

| Elimination half-life | 8.6 hours[2] |

| Excretion | Faecal (2–20%; of which, 34% as unchanged drug) and renal (40%; none as unchanged drug)[3][4] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

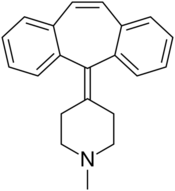

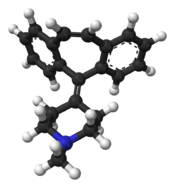

| Formula | C21H21N |

| Molar mass | 287.406 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Cyproheptadine, sold under the brand name Periactin among others, is a first-generation antihistamine with additional anticholinergic, antiserotonergic, and local anesthetic properties.

It was patented in 1959 and came into medical use in 1961.[5] In 2021, it was the 280th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 800,000 prescriptions.[6][7]

Medical uses

Cyproheptadine is used to treat allergic reactions (specifically hay fever).[8] The evidence for its use for this purpose indicates its effectiveness but second generation antihistamines such as ketotifen and loratadine have shown equal results with fewer side effects.[9]

It is also used as a preventive treatment against migraine. In a 2013 study the frequency of migraine was dramatically reduced in patients within 7 to 10 days after starting treatment. The average frequency of migraine attacks in these patients before administration was 8.7 times per month, this was decreased to 3.1 times per month at 3 months after the start of treatment.[9][10] This use is on the label in the UK and some other countries.

It is also used off-label in the treatment of cyclical vomiting syndrome in infants; the only evidence for this use comes from retrospective studies.[11]

Cyproheptadine is sometimes used off-label to improve akathisia in people on antipsychotic medications.[12]

It is used off-label to treat various dermatological conditions, including psychogenic itch[13] drug-induced hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating),[14] and prevention of blister formation for some people with epidermolysis bullosa simplex.[15]

One of the effects of the drug is increased appetite and weight gain, which has led to its use (off-label in the USA) for this purpose in children who are wasting as well as people with cystic fibrosis.[16][17][18][19]

It is also used off-label in the management of moderate to severe cases of serotonin syndrome, a complex of symptoms associated with the use of serotonergic drugs, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (and monoamine oxidase inhibitors), and in cases of high levels of serotonin in the blood resulting from a serotonin-producing carcinoid tumor.[20][21]

Cyproheptadine has sedative effects and can be used to treat insomnia similarly to other centrally-acting antihistamines.[22][23][24][25] The recommended dose for this use is 4 to 8 mg.[23]

Adverse effects

Adverse effects include:[3][4]

- Sedation and sleepiness (often transient)

- Dizziness

- Disturbed coordination

- Confusion

- Restlessness

- Excitation

- Nervousness

- Tremor

- Irritability

- Insomnia

- Paresthesias

- Neuritis

- Convulsions

- Euphoria

- Hallucinations

- Hysteria

- Faintness

- Allergic manifestation of rash and edema

- Diaphoresis

- Urticaria

- Photosensitivity

- Acute labyrinthitis

- Diplopia (seeing double)

- Vertigo

- Tinnitus

- Hypotension (low blood pressure)

- Palpitation

- Extrasystoles

- Anaphylactic shock

- Hemolytic anemia

- Blood dyscrasias such as leukopenia, agranulocytosis and thrombocytopenia

- Cholestasis

- Hepatic (liver) side effects such as:

- Epigastric distress

- Anorexia

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Anticholinergic side effects such as:

- Blurred vision

- Constipation

- Xerostomia (dry mouth)

- Tachycardia (high heart rate)

- Urinary retention

- Difficulty passing urine

- Nasal congestion

- Nasal or throat dryness

- Urinary frequency

- Early menses

- Thickening of bronchial secretions

- Tightness of chest and wheezing

- Fatigue

- Chills

- Headache

- Increased appetite

- Weight gain

Overdose

Gastric decontamination measures such as activated charcoal are sometimes recommended in cases of overdose. The symptoms are usually indicative of CNS depression (or conversely CNS stimulation in some) and excess anticholinergic side effects. The LD50 in mice is 123 mg/kg and 295 mg/kg in rats.[3][4]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | Ki (nM)[lower-alpha 1] | Action[lower-alpha 2] | Species | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | 0.06 | ↓ | Human | |

| H2 | ND | ND | ||

| H3 | >10,000 | Human | ||

| H4 | 202 | Human | ||

| M1 | 12 | ↓ | Human | |

| M2 | 7 | ↓ | Human | |

| M3 | 12 | ↓ | Human | |

| M4 | 8 | ↓ | Human | |

| M5 | 11.8 | ↓ | Human | |

| 5-HT1A | 59 | ↓ | Human | |

| 5-HT2A | 1.67 | ↓ | Human | |

| 5-HT2B | 1.54 | ↓ | Human | |

| 5-HT2C | 2.23 | ↓ | Human | |

| 5-HT3 | 228 | Mouse | ||

| 5-HT6 | 142 | Human | ||

| 5-HT7 | 123 | Human | ||

| D1 | 117 | Human | ||

| D2 | 112 | ↓ | Human | |

| D3 | 8 | Human | ||

| SERT | 4,100 | Rat | ||

| NET | 290 | Rat | ||

| DAT | ND | ND | ||

| ||||

Cyproheptadine is a very potent antihistamine or inverse agonist of the H1 receptor. At higher concentrations, it also has anticholinergic, antiserotonergic, and antidopaminergic activities. Of the serotonin receptors, it is an especially potent antagonist of the 5-HT2 receptors. This is thought to underlie its effectiveness in the treatment of serotonin syndrome.[27] However, it is possible that blockade of 5-HT1 receptors may also contribute to its effectiveness in serotonin syndrome.[28] Cyproheptadine has been reported to block 85% of 5-HT2 receptors in the human brain at a dose of 4 mg three times per day (12 mg/day total) and to block 95% of 5-HT2 receptors in the human brain at a dose of 6 mg three times per day (18 mg/day total) as measured with positron emission tomography (PET).[29] The dose of cyproheptadine recommended to ensure blockade of the 5-HT2 receptors for serotonin syndrome is 20 to 30 mg.[27] Besides its activity at neurotransmitter targets, cyproheptadine has been reported to possess weak antiandrogenic activity.[30]

Pharmacokinetics

Cyproheptadine is well-absorbed following oral ingestion, with peak plasma levels occurring after 1 to 3 hours.[31] Its terminal half-life when taken orally is approximately 8 hours.[2]

Chemistry

Cyproheptadine is a tricyclic benzocycloheptene and is closely related to pizotifen and ketotifen as well as to tricyclic antidepressants.

Research

Cyproheptadine was studied in one small trial as an adjunct in people with schizophrenia whose condition was stable and were on other medication; while attention and verbal fluency appeared to be improved, the study was too small to draw generalizations from.[32] It has also been studied as an adjuvant in two other trials in people with schizophrenia, around fifty people overall, and did not appear to have an effect.[33]

There have been some trials to see if cyproheptadine could reduce sexual dysfunction caused by SSRI and antipsychotic medications.[34]

Cyproheptadine has been studied for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder.[33]

Veterinary use

Cyproheptadine is used in cats as an appetite stimulant[35][36](p1371) and as an adjunct in the treatment of asthma.[37] Possible adverse effects include excitement and aggressive behavior.[38] The elimination half-life of cyproheptadine in cats is 12 hours.[37]

Cyproheptadine is a second line treatment for pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction in horses.[39][40]

References

- ↑ "Cyproheptadine". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House. https://www.dictionary.com/browse/Cyproheptadine.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "A comparison of the pharmacokinetics of oral and sublingual cyproheptadine". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology 42 (1): 79–83. 2004. doi:10.1081/clt-120028749. PMID 15083941.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Cyproheptadine Hydrochloride tablet [Boscogen, Inc."] (PDF). DailyMed. U.S. National Library of Medicine. November 2010. http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=f90faaa3-f40f-4653-8fb8-144d61c6b1d4.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "Product Information: Periactin (cyproheptadine hydrochloride)". Aspen Pharmacare Australia Pty Ltd. 17 November 2011. http://www.aspenpharma.com.au/product_info/pi/Periactin_PI_17Nov11.pdf.

- ↑ (in en) Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. 2006. p. 547. ISBN 9783527607495. https://books.google.com/books?id=FjKfqkaKkAAC&pg=PA547.

- ↑ "The Top 300 of 2021". https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Top300Drugs.aspx.

- ↑ "Cyproheptadine - Drug Usage Statistics". https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Cyproheptadine.

- ↑ "Cyproheptadine". MedlinePlus Drug Information. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/medmaster/a682541.html.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Are antihistamines effective in children? A review of the evidence". Archives of Disease in Childhood 102 (1): 56–60. January 2017. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2015-310416. PMID 27335428.

- ↑ "Reconsideration of the diagnosis and treatment of childhood migraine: A practical review of clinical experiences". Brain & Development 39 (5): 386–394. May 2017. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2016.11.011. PMID 27993427.

- ↑ "Pharmacological interventions on early functional gastrointestinal disorders". Italian Journal of Pediatrics 42 (1): 68. July 2016. doi:10.1186/s13052-016-0272-5. PMID 27423188.

- ↑ The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry. John Wiley & Sons. 2015. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-118-75457-3.

- ↑ "Psychogenic Itch Management". Current Problems in Dermatology 50: 124–132. 2016. doi:10.1159/000446055. ISBN 978-3-318-05888-8. PMID 27578081.

- ↑ "Cyproheptadine for drug-induced sweating". The American Journal of Psychiatry 159 (5): 874–875. May 2002. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.874-a. PMID 11986151.

- ↑ "Epidermolysis Bullosa Simplex". GeneReviews. University of Washington, Seattle. 1993. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1369/.

- ↑ "Ciproheptadina, estimulante del apetito" (in Spanish). vademecum.es. https://www.vademecum.es/principios-activos-ciproheptadina%2C+estimulante+del+apetito-a15+m1.

- ↑ "Bioplex NF". https://www.caillon.com.uy/productos_ventana.php?id=39.

- ↑ "Use of cyproheptadine to stimulate appetite and body weight gain: A systematic review". Appetite 137: 62–72. June 2019. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2019.02.012. PMID 30825493.

- ↑ "Efficacy and Tolerability of Cyproheptadine in Poor Appetite: A Multicenter, Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Study". Clinical Therapeutics 43 (10): 1757–1772. October 2021. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2021.08.001. PMID 34509304.

- ↑ Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. 2013. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- ↑ "Overview of serotonin syndrome". Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 24 (4): 310–318. November 2012. PMID 23145389.

- ↑ "Cyproheptadine: a psychopharmacological treasure trove?". CNS Spectrums 27 (5): 533–535. October 2022. doi:10.1017/S1092852921000250. PMID 33632345.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Medications Used for Pediatric Insomnia". Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 30 (1): 85–99. January 2021. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2020.09.001. PMID 33223070.

- ↑ Rombaut NE (1995). Antihistamines and Sedation: Methods and Measures (Thesis). OCLC 59660401. ProQuest 301570569.

- ↑ "Primary acquired cold urticaria. Double-blind comparative study of treatment with cyproheptadine, chlorpheniramine, and placebo". Archives of Dermatology 113 (10): 1375–1377. October 1977. doi:10.1001/archderm.113.10.1375. PMID 334082.

- ↑ "Cyproheptadine-Induced Acute Liver Failure". ACG Case Reports Journal 1 (4): 212–213. July 2014. doi:10.14309/crj.2014.56. PMID 25580444.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "The serotonin syndrome and its treatment". Journal of Psychopharmacology 13 (1): 100–109. 1999. doi:10.1177/026988119901300111. PMID 10221364.

- ↑ "The serotonin syndrome. Implicated drugs, pathophysiology and management". Drug Safety 13 (2): 94–104. August 1995. doi:10.2165/00002018-199513020-00004. PMID 7576268.

- ↑ "Cyproheptadine: a potent in vivo serotonin antagonist". The American Journal of Psychiatry 154 (6): 884a–884. June 1997. doi:10.1176/ajp.154.6.884a. PMID 9167527.

- ↑ "Treatment of androgen excess in females: yesterday, today and tomorrow". Gynecological Endocrinology 11 (6): 411–433. December 1997. doi:10.3109/09513599709152569. PMID 9476091.

- ↑ Toxicology Handbook. Elsevier Australia. 15 January 2011. p. 388. ISBN 978-0-7295-3939-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=KDOeIldGWxQC&pg=PT388. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ↑ "May non-antipsychotic drugs improve cognition of schizophrenia patients?". Pharmacopsychiatry 48 (2): 41–50. March 2015. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1396801. PMID 25584772.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 "Potential benefits of cyproheptadine in HIV-positive patients under treatment with antiretroviral drugs including efavirenz". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 13 (18): 2613–2624. December 2012. doi:10.1517/14656566.2012.742887. PMID 23140169.

- ↑ "Strategies for the treatment of antipsychotic-induced sexual dysfunction and/or hyperprolactinemia among patients of the schizophrenia spectrum: a review". Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy 38 (3): 281–301. 2012. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2011.606883. PMID 22533871.

- ↑ "Pharmacological appetite stimulation: rational choices in the inappetent cat". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 16 (9): 749–756. September 2014. doi:10.1177/1098612X14545273. PMID 25146662.

- ↑ Veterinary Toxicology : Basic and Clinical Principles (2 ed.). Amsterdam Boston: Academic Press. 2012. pp. xii+1438. ISBN 978-0-12-385926-6. OCLC 794491298.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 "Systemic Therapy of Airway Disease: Cyproheptadine". The Merck Veterinary Manual (9th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. 8 February 2005. ISBN 978-0-911910-50-6. http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/index.jsp?cfile=htm/bc/190907.htm. Retrieved on 26 October 2008.

- ↑ "Drugs Affecting Appetite". The Merck Veterinary Manual (9th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. 8 February 2005. ISBN 978-0-911910-50-6. http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/index.jsp?cfile=htm/bc/190302.htm. Retrieved on 26 October 2008.

- ↑ "Therapeutics for Equine Endocrine Disorders". The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Equine Practice 33 (1): 127–139. April 2017. doi:10.1016/j.cveq.2016.11.003. PMID 28190613.

- ↑ "Hirsutism Associated with Adenomas of the Pars Intermedia". Merck Vet Manual. July 2019. https://www.merckvetmanual.com/endocrine-system/the-pituitary-gland/hypertrichosis-associated-with-adenomas-of-the-pars-intermedia.

|