Chemistry:Melatonin as a medication and supplement

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌmɛləˈtoʊnɪn/ ( |

| Trade names | Circadin, Slenyto, others[1] |

| Other names | N-Acetyl-5-methoxy tryptamine[2] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Consumer Drug Information |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | Physical: Low[4] Psychological: Low[4] |

| Addiction liability | Low / none[4] |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, sublingual, transdermal |

| Drug class | Melatonin receptor agonist |

| ATC code | |

| Physiology data | |

| Source tissues | Pineal gland |

| Target tissues | Widespread, including brain, retina, and circulatory system |

| Receptors | Melatonin receptor |

| Precursor | N-Acetylserotonin |

| Metabolism | Liver via CYP1A2 mediated 6-hydroxylation |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 2.5–50%[5][6][7] |

| Protein binding | 60%[7] |

| Metabolism | Liver via CYP1A2 mediated 6-hydroxylation |

| Metabolites | 6-Hydroxymelatonin, N-acetyl-5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-methoxytryptamine |

| Elimination half-life | IR: 20–60 minutes[6][8][9] PR: 3.5–4 hours[10][7] |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C13H16N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 232.283 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 117 °C (243 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Melatonin is a dietary supplement and medication as well as naturally occurring hormone.[8][11] As a hormone, melatonin is released by the pineal gland and is involved in sleep–wake cycles.[8][11] As a supplement, it is often used for the attempted short-term treatment of disrupted sleep patterns, such as from jet lag or shift work, and is typically taken orally.[12][13][14] Evidence of its benefit for this use, however, is not strong.[15] A 2017 review found that sleep onset occurred six minutes faster with use, but found no change in total time asleep.[13]

Side effects from melatonin supplements are minimal at low doses for short durations (in the studies reported about equally for both melatonin and placebo).[8][16] Side effects of melatonin are rare but may occur in 1 to 10 patients in 1,000.[16][7] They may include somnolence (sleepiness), headaches, nausea, diarrhea, abnormal dreams, irritability, nervousness, restlessness, insomnia, anxiety, migraine, lethargy, psychomotor hyperactivity, dizziness, hypertension, abdominal pain, heartburn, mouth ulcers, dry mouth, hyperbilirubinaemia, dermatitis, night sweats, pruritus, rash, dry skin, pain in the extremities, symptoms of menopause, chest pain, glycosuria (sugar in the urine), proteinuria (protein in the urine), abnormal liver function tests, increased weight, tiredness, mood swings, aggression and feeling hungover.[7][17][16][18][19] Its use is not recommended during pregnancy or breastfeeding or for those with liver disease.[14][19]

Melatonin acts as an agonist of the melatonin MT1 and MT2 receptors, the biological targets of endogenous melatonin.[20] It is thought to activate these receptors in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus in the brain to regulate the circadian clock and sleep–wake cycles.[20] Immediate-release melatonin has a short elimination half-life of about 20 to 50 minutes.[21][8][9] Prolonged-release melatonin used as a medication has a half-life of 3.5 to 4 hours.[10][7]

Melatonin was discovered in 1958.[8] It is sold over the counter in Canada and the United States;[16][18] in the United Kingdom, it is a prescription-only medication.[14] In Australia and the European Union, it is indicated for difficulty sleeping in people over the age of 54.[22][7] In the European Union, it is indicated for the treatment of insomnia in children and adolescents.[17] The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) treats melatonin as a dietary supplement and as such has not approved it for any medical uses.[16] It was approved for medical use in the European Union in 2007.[7] Besides melatonin, certain synthetic melatonin receptor agonists like ramelteon, tasimelteon, and agomelatine are also used in medicine.[23][24] In 2021, it was the 257th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 1 million prescriptions.[25][26]

Medical uses

Insomnia

There is no good evidence that melatonin helps treat insomnia and its attempted use for this purpose is recommended against by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine.[27]

A prolonged-release form of melatonin is also approved for use as a medication in Europe for the treatment of insomnia in certain people.[10][28]

Circadian rhythm sleep disorders

Melatonin may be useful in the treatment of delayed sleep phase syndrome.[8]

Melatonin is known to reduce jet lag, especially in eastward travel. However, if it is not taken at the correct time, it can instead delay adaptation.[29]

Melatonin appears to have limited use against the sleep problems of people who work shift work.[30] Tentative evidence suggests that it increases the length of time people are able to sleep.[30]

REM sleep behavior disorder

Melatonin is a safer alternative than clonazepam in the treatment of REM sleep behavior disorder – a condition associated with the synucleinopathies like Parkinson's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies.[31][32][33] However, clonazepam may be more effective.[34] In any case, the quality of evidence for both treatments is very low and it is unclear whether either is definitely effective.[34]

Dementia

A 2020 Cochrane review found no evidence that melatonin helped sleep problems in people with moderate to severe dementia due to Alzheimer's disease.[35] A 2019 review found that while melatonin may improve sleep in minimal cognitive impairment, after the onset of Alzheimer's disease it has little to no effect.[36] Melatonin may, however, help with sundowning (increased confusion and restlessness at night) in people with dementia.[37]

Available forms

A prolonged-release 2 mg oral formulation of melatonin sold under the brand name Circadin is approved for use in the European Union in the short-term treatment of insomnia in people age 55 and older.[10][28][7]

Melatonin is also available as an over-the-counter dietary supplement in many countries. It is available in both immediate-release and less commonly prolonged-release forms. The compound is available in supplements at doses ranging from 0.3 mg to 10 mg or more. It is also possible to buy raw melatonin powder by the weight.[38] Immediate-release formulations of melatonin cause blood levels of melatonin to reach their peak in about an hour. The hormone may be administered orally, as capsules, gummies, tablets, or liquids. It is also available for use sublingually, or as transdermal patches.[39]

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) said that the melatonin content in unregulated (without a USP verified mark) supplements can diverge widely from the claimed amount; a study found that the melatonin content ranged from one half to four times the stated dose.[40]

Contraindications

Contraindications of melatonin include hypersensitivity reactions among others.[7] It is not recommended in people with autoimmune diseases due to lack of data in these individuals.[7] Prolonged-release pharmaceutical melatonin (Circadin) contains lactose and should not be used in people with the lactase deficiency or glucose–galactose malabsorption.[7] Use of melatonin is also not recommend in women who are pregnant or breastfeeding or in people with liver disease.[14][19]

Adverse effects

Melatonin appears to cause very few side effects as tested in the short term, up to three months, at low doses.[clarification needed]Template:Dubious inline Two systematic reviews found no adverse effects of exogenous melatonin in several clinical trials, and comparative trials found the adverse effects headaches, dizziness, nausea, and drowsiness were reported about equally for both melatonin and placebo.[41][42] Prolonged-release melatonin is safe with long-term use of up to 12 months.[10] Although not recommended for long-term use beyond this,[43] low-dose melatonin is generally safer, and a better alternative, than many prescription and over-the-counter sleep aids if a sleeping medication must be used for an extended period of time.[citation needed] Low doses of melatonin are usually sufficient to produce a hypnotic effect in most people. Higher doses do not appear to result in a stronger effect but instead appear to cause drowsiness for a longer period of time.[44]

There is emerging evidence that the timing of taking exogenous melatonin in relation to food is also an important factor.[45] Specifically, taking exogenous melatonin shortly after a meal is correlated with impaired glucose tolerance. Therefore, Rubio-Sastre and colleagues recommend waiting at least 2 hours after the last meal before taking a melatonin supplement.[46]

Melatonin can cause nausea, next-day grogginess, and irritability.[47] In autoimmune disorders, evidence is conflicting whether melatonin supplementation may ameliorate or exacerbate symptoms due to immunomodulation.[48][49][needs update]

Melatonin can lower follicle-stimulating hormone levels.[50] Melatonin's effects on human reproduction remain unclear.[51]

Some supplemental melatonin users report an increase in vivid dreaming.[52][unreliable medical source?] Extremely high doses of melatonin increased REM sleep time and dream activity in people both with and without narcolepsy.[53]

Increased use of melatonin in the 21st century has significantly increased reports of melatonin overdose, calls to poison control centers, and related emergency department visits for children. The number of children who unintentionally ingested melatonin supplements in the US has increased 530% from 2012 to 2021. Over 4,000 reported ingestions required a hospital stay, and 287 children required intensive care. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine says there is little evidence that melatonin supplementation is effective in treating insomnia in healthy children.[40]

Overdose

Melatonin appears to be relatively safe in overdose.[7] It has been administered at daily doses of up to 300 mg without causing clinically significant adverse reactions in the literature.[7] The most commonly reported adverse effect of melatonin overdose is somnolence.[7] Upon melatonin overdose, drowsiness may be expected and the compound should be cleared within 12 hours.[7] No special treatment is needed for melatonin overdose.[7]

Interactions

Melatonin is metabolized mainly by CYP1A enzymes. As such, inhibitors and inducers of CYP1A enzymes, such as CYP1A2, can modify melatonin metabolism and exposure.[7] As an example, the CYP1A2 and CYP2C19 inhibitor fluvoxamine increases melatonin peak levels by 12-fold and overall exposure by 17-fold and this combination should be avoided.[7] CYP1A2 inducers like cigarette smoking, carbamazepine, and rifampicin may reduce melatonin exposure due to induction of CYP1A2.[7]

In those taking warfarin, some evidence suggests there may exist a potentiating interaction, increasing the anticoagulant effect of warfarin and the risk of bleeding.[54]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Melatonin acts as an agonist of the melatonin MT1 and MT2 receptors, the biological targets of endogenous melatonin.[20] Endogenous melatonin is normally secreted from the pineal gland of the brain.[20] Melatonin is thought to activate melatonin receptors in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus to regulate the circadian clock and sleep–wake cycles.[20] When used several hours before sleep according to the phase response curve for melatonin in humans, small amounts (0.3 mg[55]) of melatonin shift the circadian clock earlier, thus promoting earlier sleep onset and morning awakening.[56]

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

The bioavailability of melatonin is between 2.5 and 50%.[5][6] Melatonin is rapidly absorbed and distributed, reaching peak plasma concentrations after 60 minutes of administration, and is then eliminated.[5] Usual doses of exogenous melatonin of 1 to 12 mg produce melatonin concentrations 10 to 100 times higher than endogenous peak levels.[6]

Distribution

The plasma protein binding of melatonin is approximately 60%.[7][6] It is mainly bound to albumin, α1-acid glycoprotein, and high-density lipoprotein.[7]

The membrane transport proteins that move melatonin across a membrane include, but are not limited to, glucose transporters, including GLUT1, and the proton-driven oligopeptide transporters PEPT1 and PEPT2.[57][58]

Metabolism

Melatonin is metabolized in the liver by cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP1A2 to 6-hydroxymelatonin. Metabolites are conjugated with sulfuric acid or glucuronic acid for excretion in the urine. Some of the metabolites formed via the reaction of melatonin with a free radical include cyclic 3-hydroxymelatonin, N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine (AFMK), and N1-acetyl-5-methoxykynuramine (AMK).[57][58]

Elimination

In humans, 90% of orally administered exogenous melatonin is cleared in a single passage through the liver, a small amount is excreted in urine, and a small amount is found in saliva.[12] Melatonin is excreted in the urine 2 to 5% as the unchanged drug.[5][7]

Melatonin has an elimination half-life of about 20 to 60 minutes.[21][6][8][9] The half-life of prolonged-release melatonin (Circadin) is 3.5 to 4 hours.[10][7]

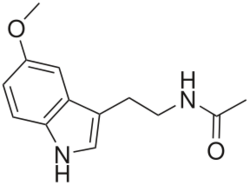

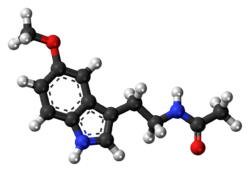

Chemistry

Melatonin, also known as N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine, is a substituted tryptamine and a derivative of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine). It is structurally related to N-acetylserotonin (normelatonin; N-acetyl-5-hydroxytryptamine), which is the chemical intermediate between serotonin and melatonin in the body. Synthetic melatonin receptor agonists used in medicine like ramelteon, tasimelteon, agomelatine, and piromelatine (still in clinical trials) are analogues of melatonin.

History

The first patent for its use in circadian rhythm disorders was granted in 1987 to Roger V Short and Stuart Armstrong at Monash University,[59] and the first patent for its use as a low-dose sleep aid was granted to Richard Wurtman at MIT in 1995.[60] Around the same time, the hormone got a lot of press as a possible treatment for many illnesses.[61] The New England Journal of Medicine editorialized in 2000: "With these recent careful and precise observations in blind persons, the true potential of melatonin is becoming evident, and the importance of the timing of treatment is becoming clear."[62]

It was approved for medical use in the European Union in 2007.[7]

Society and culture

Melatonin is categorized by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a dietary supplement, and is sold over-the-counter in both the US and Canada.[12] FDA regulations applying to medications are not applicable to melatonin,[63] though the FDA has found false claims that it cures cancer.[64] As melatonin may cause harm in combination with certain medications or in the case of certain disorders, a doctor or pharmacist should be consulted before making a decision to take melatonin.[29] In many countries, melatonin is recognized as a neurohormone and it cannot be sold over-the-counter.[65] According to Harriet Hall caution is advisable, since quality control is a documented problem. 71% of products did not contain within 10% of the labelled amount of melatonin, with variations ranging from -83% to +478%, lot-to-lot variability was as high as 465%, and the discrepancies were not correlated to any manufacturer or product type. To make matters worse, 8 out of 31 products were contaminated with the neurotransmitter serotonin.[66][67]

Formerly, melatonin was derived from animal pineal tissue, such as bovine. It is now synthetic, which limits the risk of contamination or the means of transmitting infectious material.[63][68]

Melatonin is the most popular over-the-counter sleep remedy in the United States, resulting in sales in excess of US$400 million during 2017.[69] In 2021, it was the 257th most commonly prescribed medication in the US, with more than 1 million prescriptions.[25][26]

Beverages and snacks containing melatonin were being sold in grocery stores, convenience stores, and clubs in May 2011.[70] The FDA considered whether these food products could continue to be sold with the label "dietary supplements". On 13 January 2010, it issued a Warning Letter to Innovative Beverage, creators of several beverages marketed as drinks, stating that melatonin, while legal as a dietary supplement, was not approved as a food additive.[71] Bebida Beverage Company received a warning letter in 2015 for selling a melatonin-containing beverage.[72]

Research

Psychiatry

Depression

Some research supports an antidepressant effect of melatonin.[73]

Bipolar disorder

Melatonin, along with ramelteon, has been repurposed as a possible adjunctive treatment for manic episodes in bipolar disorder.[74] However, meta-analytic evidence is somehow inconsistent and of limited interest so far, although the small samples of trials do not allow ruling out its beneficial effect.[74] In any case, current evidence does not support the use of add-on melatonin-receptor agonists for mania.[74]

Anxiety

Melatonin in comparison to placebo is effective for reducing preoperative anxiety in adults when given as premedication. It may be just as effective as standard treatment with benzodiazepine in reducing preoperative anxiety. Melatonin may also reduce postoperative anxiety (measured 6 hours after surgery) when compared to placebo.[75]

Headaches

Tentative evidence shows melatonin may help reduce some types of headaches including cluster and hypnic headaches.[76][77]

Cancer

A 2013 review by the National Cancer Institute found insufficient evidence for melatonin having anti-cancer effects.[78] A 2022 review found that melatonin supplementation had a small improvement in survival of people with cancer at one year.[79][80] One review found that melatonin may alleviate chemotherapy-related side effects.[81]

Protection from radiation

Both animal[82] and human[83][84][85] studies have shown melatonin to protect against radiation-induced cellular damage. Melatonin and its metabolites protect organisms from oxidative stress by scavenging reactive oxygen species which are generated during exposure.[86] Nearly 70% of biological damage caused by ionizing radiation is estimated to be attributable to the creation of free radicals, especially the hydroxyl radical that attacks DNA, proteins, and cellular membranes. Melatonin has been described as a broadly protective, readily available, and orally self-administered antioxidant that is without known, major side effects.[87]

Epilepsy

A 2016 review found no beneficial role of melatonin in reducing seizure frequency or improving quality of life in people with epilepsy.[88]

Dysmenorrhea

A 2016 review suggested no strong evidence of melatonin compared to placebo for dysmenorrhea secondary to endometriosis.[89]

Delirium

A 2016 review suggested no clear evidence of melatonin to reduce the incidence of delirium.[90]

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

A 2011 review said melatonin is effective in relieving epigastric pain and heartburn.[91]

Tinnitus

A 2015 review of studies of melatonin in tinnitus found the quality of evidence low, but not entirely without promise.[92]

References

- ↑ "Melatonin – Drugs.com". Drugs.com. https://www.drugs.com/international/melatonin.html.

- ↑ "Melatonin". Sleepdex. http://www.sleepdex.org/melatonin.htm.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 https://www.tga.gov.au/resources/auspar/auspar-melatonin-1

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Pros and cons of melatonin" (in en). https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/adult-health/expert-answers/melatonin-side-effects/faq-20057874.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 "Melatonin: Pharmacology, Functions and Therapeutic Benefits". Current Neuropharmacology 15 (3): 434–443. April 2017. doi:10.2174/1570159X14666161228122115. PMID 28503116.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 "Melatonin: From Pharmacokinetics to Clinical Use in Autism Spectrum Disorder". Int J Mol Sci 22 (3): 1490. February 2021. doi:10.3390/ijms22031490. PMID 33540815.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 7.19 7.20 7.21 7.22 7.23 7.24 Circadin: EPAR - Product Information ANNEX I - SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS (Report). European Medicines Agency (EMA). 2 February 2021. EMEA/H/C/000695 - IA/0066. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/circadin. As PDF. Text was copied from this source which is © European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 "Evidence for the efficacy of melatonin in the treatment of primary adult sleep disorders". Sleep Medicine Reviews 34: 10–22. August 2017. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2016.06.005. PMID 28648359. http://epubs.surrey.ac.uk/813219/1/Riha%20accepted%20MS%202016.pdf.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "Melatonergic drugs in clinical practice". Arzneimittelforschung 58 (1): 1–10. 2008. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1296459. PMID 18368944.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 "Melatonin prolonged release: in the treatment of insomnia in patients aged ≥55 years". Drugs & Aging 29 (11): 911–23. November 2012. doi:10.1007/s40266-012-0018-z. PMID 23044640.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 ADHD: Non-Pharmacologic Interventions, An Issue of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2014. p. 888. ISBN 978-0-323-32602-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=lNSlBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA888.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 "Melatonin for treatment of sleep disorders". Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 108. (Prepared by the University of Alberta Evidence-based Practice Center, Under Contract No. 290-02-0023.) AHRQ Publication No. 05-E002-2. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), US Department of Health and Human Services) (108): 1–7. November 2004. doi:10.1037/e439412005-001. PMID 15635761. PMC 4781368. http://archive.ahrq.gov/downloads/pub/evidence/pdf/melatonin/melatonin.pdf. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Insomnia: Pharmacologic Therapy". American Family Physician 96 (1): 29–35. July 2017. PMID 28671376.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. pp. 482–483. ISBN 978-0-85711-338-2.

- ↑ "Management of Insomnia Disorder[Internet]". AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews 15 (16): EHC027–EF. 2015. PMID 26844312. "Evidence for benzodiazepine hypnotics, melatonin agonists in the general adult population, and most pharmacologic interventions in older adults was generally insufficient".

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 "Melatonin: Side Effects, Uses, Dosage (Kids/Adults)". https://www.drugs.com/melatonin.html.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Slenyto EPAR". 17 September 2018. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/slenyto. Text was copied from this source which is © European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Summary Safety Review – MELATONIN (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine) – Review of the Safety of Melatonin in Children and Adolescents". Health Canada. 10 December 2015. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/medeffect-canada/safety-reviews/summary-safety-review-melatonin-acetyl-methoxytryptamine-review-safety-melatonin-children-adolescents.html.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 "Melatonin- Oral". Health Canada. 28 August 2018. http://webprod.hc-sc.gc.ca/nhpid-bdipsn/atReq.do?atid=melatonin.oral&lang=eng.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 "Melatonin and the circadian system: Keys for health with a focus on sleep". The Human Hypothalamus: Anterior Region. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 179. 2021. pp. 331–343. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-819975-6.00021-2. ISBN 9780128199756.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Melatonin". https://www.drugbank.ca/drugs/DB01065.

- ↑ "Australian Public Assessment Report for Melatonin". January 2011. pp. 2, 4. https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/auspar-circadin-110118.pdf. "Monotherapy for the short term treatment of primary insomnia characterised by poor quality of sleep in patients who are aged 55 or over."

- ↑ "Comparative Review of Approved Melatonin Agonists for the Treatment of Circadian Rhythm Sleep-Wake Disorders". Pharmacotherapy 36 (9): 1028–41. September 2016. doi:10.1002/phar.1822. PMID 27500861.

- ↑ "Drugs for Insomnia beyond Benzodiazepines: Pharmacology, Clinical Applications, and Discovery". Pharmacol Rev 70 (2): 197–245. April 2018. doi:10.1124/pr.117.014381. PMID 29487083.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "The Top 300 of 2021". https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Top300Drugs.aspx.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "Melatonin - Drug Usage Statistics". https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Melatonin.

- ↑ "Chapter 10: Insomnia". Pseudoscience in Therapy: A Skeptical Field Guide. Cambridge University Press. 2023. pp. 147–148. doi:10.1017/9781009000611.011. ISBN 9781009000611.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "Prolonged-release melatonin for the treatment of insomnia in patients over 55 years". Expert Opin Investig Drugs 17 (10): 1567–72. October 2008. doi:10.1517/13543784.17.10.1567. PMID 18808316.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "Melatonin for the prevention and treatment of jet lag". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010 (2): CD001520. 2002. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001520. PMID 12076414.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "Pharmacological interventions for sleepiness and sleep disturbances caused by shift work". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014 (8): CD009776. August 2014. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009776.pub2. PMID 25113164.

- ↑ "Treatment outcomes in REM sleep behavior disorder". Sleep Medicine 14 (3): 237–42. March 2013. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2012.09.018. PMID 23352028.

- ↑ "Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium". Neurology 89 (1): 88–100. July 2017. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000004058. PMID 28592453.

- ↑ "Comprehensive treatment of dementia with Lewy bodies". Alzheimer's Research & Therapy 7 (1): 45. 2015. doi:10.1186/s13195-015-0128-z. PMID 26029267.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "A critical review of the pharmacological treatment of REM sleep behavior disorder in adults: time for more and larger randomized placebo-controlled trials". J Neurol 269 (1): 125–148. January 2022. doi:10.1007/s00415-020-10353-0. PMID 33410930.

- ↑ "Pharmacotherapies for sleep disturbances in dementia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2020 (11): CD009178. November 2020. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009178.pub4. PMID 33189083.

- ↑ "Neuroendocrine-Metabolic Dysfunction and Sleep Disturbances in Neurodegenerative Disorders: Focus on Alzheimer's Disease and Melatonin". Neuroendocrinology 108 (4): 354–364. 2019. doi:10.1159/000494889. PMID 30368508. https://repositorio.uca.edu.ar/handle/123456789/9108.

- ↑ "Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia". Handbook of Sleep Disorders in Medical Conditions. Academic Press. 2019. pp. 253–276. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-813014-8.00011-1. ISBN 978-0-12-813014-8.

- ↑ "Melatonin Product Availability". 28 February 2021. https://keldik.com/blogs/sleep-circadian-binnacle/melatonin-product-availability.

- ↑ "Melatonin and health: an umbrella review of health outcomes and biological mechanisms of action". BMC Medicine 16 (1): 18. February 2018. doi:10.1186/s12916-017-1000-8. PMID 29397794.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 "Experts Issue Health Warning About Giving Melatonin to Kids". 23 September 2022. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/981341.

- ↑ "The efficacy and safety of exogenous melatonin for primary sleep disorders. A meta-analysis". Journal of General Internal Medicine 20 (12): 1151–8. December 2005. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0243.x. PMID 16423108.

- ↑ "Efficacy and safety of exogenous melatonin for secondary sleep disorders and sleep disorders accompanying sleep restriction: meta-analysis". BMJ 332 (7538): 385–93. February 2006. doi:10.1136/bmj.38731.532766.F6. PMID 16473858.

- ↑ "Melatonin: What You Need To Know". National Institutes of Health. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/melatonin-what-you-need-to-know.

- ↑ Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE): Quality-assessed Reviews [Internet]. York (UK): Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (UK); 1995. Optimal dosages for melatonin supplementation therapy in older adults: a systematic review of current literature. 2014.

- ↑ "Melatonin Effects on Glucose Metabolism: Time To Unlock the Controversy". Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism 31 (3): 192–204. March 2020. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2019.11.011. PMID 31901302.

- ↑ "Acute melatonin administration in humans impairs glucose tolerance in both the morning and evening". Sleep 37 (10): 1715–9. October 2014. doi:10.5665/sleep.4088. PMID 25197811.

- ↑ "Melatonin side effects: What are the risks?". Mayo Clinic. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/melatonin-side-effects/AN01717.

- ↑ "[Safety in melatonin use]" (in es). Actas Españolas de Psiquiatría 29 (5): 334–7. 2001. PMID 11602091.

- ↑ "Melatonin and ulcerative colitis: evidence, biological mechanisms, and future research". Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 15 (1): 134–40. January 2009. doi:10.1002/ibd.20527. PMID 18626968.

- ↑ "[The effect of melatonin on prolactin, luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) synthesis and secretion"] (in pl). Postepy Higieny I Medycyny Doswiadczalnej 60: 431–8. 2006. PMID 16921343. http://www.phmd.pl/fulltxthtml.php?ICID=453297. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ↑ "Melatonin and human reproduction: shedding light on the darkness hormone". Gynecological Endocrinology 25 (12): 779–85. December 2009. doi:10.3109/09513590903159649. PMID 19905996.

- ↑ "Vivid dreaming". https://dreamifiel.com/blog/vivid-dreams-during-pregnancy/.

- ↑ Melatonin and the Biological Clock. McGraw-Hill. 1999. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-87983-734-1. https://archive.org/details/melatoninbiologi00lew_46r.

- ↑ "Melatonin – Special Subjects". https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/special-subjects/dietary-supplements/melatonin?query=melatonin.

- ↑ "Phase-dependent treatment of delayed sleep phase syndrome with melatonin". Sleep 28 (10): 1271–8. October 2005. doi:10.1093/sleep/28.10.1271. PMID 16295212.

- ↑ Chronotherapeutics for Affective Disorders: A Clinician's Manual for Light and Wake Therapy. Basel: S Karger Pub. 2009. p. 71. ISBN 978-3-8055-9120-1. https://archive.org/details/chronotherapeuti00wirz.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 "Update on melatonin receptors: IUPHAR Review 20". British Journal of Pharmacology 173 (18): 2702–25. September 2016. doi:10.1111/bph.13536. PMID 27314810.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 "Melatonin transport into mitochondria". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 74 (21): 3927–3940. November 2017. doi:10.1007/s00018-017-2616-8. PMID 28828619.

- ↑ "Method for minimizing disturbances in circadian rhythms of bodily performance and function - Patent US-4665086-A - PubChem". https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/patent/US-4665086-A.

- ↑ Wurtman RJ, "Methods of inducing sleep using melatonin", US patent 5449683, issued 12 September 1995, assigned to Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- ↑ "Melatonin: characteristics, concerns, and prospects". Journal of Biological Rhythms 20 (4): 291–303. August 2005. doi:10.1177/0748730405277492. PMID 16077149. "There is very little evidence in the short term for toxicity or undesirable effects in humans. The extensive promotion of the miraculous powers of melatonin in the recent past did a disservice to acceptance of its genuine benefits.".

- ↑ "Melatonin, circadian rhythms, and sleep". The New England Journal of Medicine 343 (15): 1114–6. October 2000. doi:10.1056/NEJM200010123431510. PMID 11027748.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 "Melatonin: therapeutic and clinical utilization". International Journal of Clinical Practice 61 (5): 835–45. May 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01191.x. PMID 17298593.

- ↑ "187 Fake Cancer 'Cures' Consumers Should Avoid". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/EnforcementActivitiesbyFDA/ucm171057.htm.

- ↑ "Toxicology of melatonin". Journal of Biological Rhythms 12 (6): 697–706. December 1997. doi:10.1177/074873049701200627. PMID 9406047.

- ↑ "Melatonin Melatonin supplements are increasingly popular, but the evidence is weak and mixed.". Science-Based Medicine. Science Based Medicine. 15 December 2020. https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/melatonin/.

- ↑ "Melatonin Natural Health Products and Supplements: Presence of Serotonin and Significant Variability of Melatonin Content". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 13 (2): 275–281. February 2017. doi:10.5664/jcsm.6462. PMID 27855744.

- ↑ "Melatonin". Drugs.com. https://www.drugs.com/melatonin.html.

- ↑ "Does Melatonin Really Help You Sleep?". https://www.consumerreports.org/vitamins-supplements/does-melatonin-really-help-you-sleep/.

- ↑ "Dessert, Laid-Back and Legal". The New York Times. 14 May 2011. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/15/us/15lazycakes.html.

- ↑ "Warning Letter". Inspections, Compliance, Enforcement, and Criminal Investigations. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 13 January 2010. http://www.fda.gov/ICECI/EnforcementActions/WarningLetters/2010/ucm201435.htm.

- ↑ "Bebida Beverage Company". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 4 March 2015. https://www.fda.gov/ICECI/EnforcementActions/WarningLetters/2015/ucm440953.htm.

- ↑ "Circadian modulation of neuroplasticity by melatonin: a target in the treatment of depression". British Journal of Pharmacology 175 (16): 3200–3208. August 2018. doi:10.1111/bph.14197. PMID 29512136.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 "Repurposed drugs as adjunctive treatments for mania and bipolar depression: A meta-review and critical appraisal of meta-analyses of randomized placebo-controlled trials". Journal of Psychiatric Research 143: 230–238. September 2021. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.09.018. PMID 34509090.

- ↑ "Melatonin for pre- and postoperative anxiety in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2020 (12): CD009861. 8 December 2020. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009861.pub3. PMID 33319916.

- ↑ "Potential therapeutic use of melatonin in migraine and other headache disorders". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs 15 (4): 367–75. April 2006. doi:10.1517/13543784.15.4.367. PMID 16548786.

- ↑ "Review: Hypnic headache". Practical Neurology 5 (3): 144–49. 2005. doi:10.1111/j.1474-7766.2005.00301.x. http://pn.bmj.com/content/practneurol/5/3/144.full.pdf. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- ↑ "Topics in complementary and alternative therapies". PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. May 2013. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK126745/#CDR0000745420__16.

- ↑ "Effects of exogenous melatonin supplementation on health outcomes: An umbrella review of meta-analyses based on randomized controlled trials". Pharmacological Research 176: 106052. February 2022. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2021.106052. PMID 34999224. https://arro.anglia.ac.uk/id/eprint/707412/1/Lim_et_al_2022.pdf.

- ↑ "Melatonin and health: an umbrella review of health outcomes and biological mechanisms of action". BMC Medicine 16 (1): 18. February 2018. doi:10.1186/s12916-017-1000-8. PMID 29397794.

- ↑ "The efficacy and safety of melatonin in concurrent chemotherapy or radiotherapy for solid tumors: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology 69 (5): 1213–1220. May 2012. doi:10.1007/s00280-012-1828-8. PMID 22271210.

- ↑ "Melatonin and protection from whole-body irradiation: survival studies in mice". Mutation Research 425 (1): 21–7. March 1999. doi:10.1016/S0027-5107(98)00246-2. PMID 10082913.

- ↑ "Melatonin and radioprotection from genetic damage: in vivo/in vitro studies with human volunteers". Mutation Research 371 (3–4): 221–8. December 1996. doi:10.1016/S0165-1218(96)90110-X. PMID 9008723.

- ↑ "Dietary supplements for dysmenorrhoea". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016 (3): CD002124. March 2016. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd002124.pub2. PMID 27000311.

- ↑ "Melatonin reduces gamma radiation-induced primary DNA damage in human blood lymphocytes". Mutation Research 397 (2): 203–8. February 1998. doi:10.1016/S0027-5107(97)00211-X. PMID 9541644.

- ↑ "One molecule, many derivatives: a never-ending interaction of melatonin with reactive oxygen and nitrogen species?". Journal of Pineal Research 42 (1): 28–42. January 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00407.x. PMID 17198536.

- ↑ "A radiobiological review on melatonin: a novel radioprotector". Journal of Radiation Research 48 (4): 263–72. July 2007. doi:10.1269/jrr.06070. PMID 17641465. Bibcode: 2007JRadR..48..263S.

- ↑ "Melatonin as add-on treatment for epilepsy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016 (8): CD006967. August 2016. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006967.pub4. PMID 27513702.

- ↑ "Dietary supplements for dysmenorrhoea". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016 (3): CD002124. March 2016. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002124.pub2. PMID 27000311.

- ↑ "Interventions for preventing delirium in hospitalised non-ICU patients". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016 (3): CD005563. March 2016. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005563.pub3. PMID 26967259. PMC 10431752. http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/99189/7/Siddiqi_et_al-2016-The_Cochrane_Library.pdf.

- ↑ "The potential therapeutic effect of melatonin in Gastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease". BMC Gastroenterology 10: 7. January 2010. doi:10.1186/1471-230X-10-7. PMID 20082715.

- ↑ "Clinical pharmacology of melatonin in the treatment of tinnitus: a review". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 71 (3): 263–70. March 2015. doi:10.1007/s00228-015-1805-3. PMID 25597877.

|