Chemistry:Quazepam

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Doral |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Consumer Drug Information |

| MedlinePlus | a684001 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 29–35% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 39 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

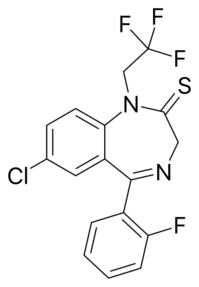

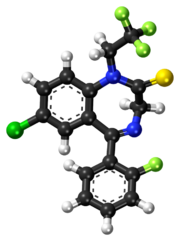

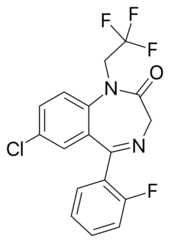

| Formula | C17H11ClF4N2S |

| Molar mass | 386.79 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Quazepam, sold under brand name Doral among others, is a relatively long-acting benzodiazepine derivative drug developed by the Schering Corporation in the 1970s.[1] Quazepam is used for the treatment of insomnia including sleep induction and sleep maintenance.[2] Quazepam induces impairment of motor function and has relatively (and uniquely) selective hypnotic and anticonvulsant properties with considerably less overdose potential than other benzodiazepines (due to its novel receptor-subtype selectivity).[3][4] Quazepam is an effective hypnotic which induces and maintains sleep without disruption of the sleep architecture.[5]

It was patented in 1970 and came into medical use in 1985.[6]

Medical uses

Quazepam is used for short-term treatment of insomnia related to sleep induction or sleep maintenance problems and has demonstrated superiority over other benzodiazepines such as temazepam. It had a fewer incidence of side effects than temazepam, including less sedation, amnesia, and less motor-impairment.[7][8][9][10] Usual dosage is 7.5 to 15 mg orally at bedtime.[11]

Quazepam is effective as a premedication prior to surgery.[12]

Side effects

Quazepam has fewer side effects than other benzodiazepines and less potential to induce tolerance and rebound effects.[13][14] There is significantly less potential for quazepam to induce respiratory depression or to adversely affect motor coordination than other benzodiazepines.[15] The different side effect profile of quazepam may be due to its more selective binding profile to type 1 benzodiazepine receptors.[16][17]

- Ataxia[18]

- Daytime somnolence[19]

- Hypokinesia[20]

- Cognitive and performance impairments[21]

In September 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) required the boxed warning be updated for all benzodiazepine medicines to describe the risks of abuse, misuse, addiction, physical dependence, and withdrawal reactions consistently across all the medicines in the class.[22]

Tolerance and dependence

Tolerance may occur to quazepam but more slowly than seen with other benzodiazepines such as triazolam.[23] Quazepam causes significantly less drug tolerance and less withdrawal symptoms including less rebound insomnia upon discontinuation compared to other benzodiazepines.[24][25][26][27] Quazepam may cause less rebound effects than other type1 benzodiazepine receptor selective nonbenzodiazepine drugs due to its longer half-life.[28] Short-acting hypnotics often cause next day rebound anxiety. Quazepam due to its pharmacological profile does not cause next day rebound withdrawal effects during treatment.[29]

No firm conclusions can be drawn, however, whether long-term use of quazepam does not produce tolerance as few, if any, long-term clinical trials extending beyond 4 weeks of chronic use have been conducted.[30] Quazepam should be withdrawn gradually if used beyond 4 weeks of use to avoid the risk of a severe benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome developing. Very high dosage administration over prolonged periods of time, up to 52 weeks, of quazepam in animal studies provoked severe withdrawal symptoms upon abrupt discontinuation, including excitability, hyperactivity, convulsions and the death of two of the monkeys due to withdrawal-related convulsions. More monkeys died however, in the diazepam-treated monkeys.[31] In addition it has now been documented in the medical literature that one of the major metabolites of quazepam, N-desalkyl-2-oxoquazepam (N-desalkylflurazepam), which is long-acting and prone to accumulation, binds unselectively to benzodiazepine receptors, thus quazepam may not differ all that much pharmacologically from other benzodiazepines.[32]

Special precautions

Benzodiazepines require special precaution if used in the during pregnancy, in children, alcohol or drug-dependent individuals and individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders.[33]

Quazepam and its active metabolites are excreted into breast milk.[34]

Accumulation of one of the active metabolites of quazepam, N-desalkylflurazepam, may occur in the elderly. A lower dose may be required in the elderly.[35]

Elderly

Quazepam is more tolerable for elderly patients compared to flurazepam due to its reduced next day impairments.[36] However, another study showed marked next day impairments after repeated administration due to accumulation of quazepam and its long-acting metabolites. Thus the medical literature shows conflicts on quazepam's side effect profile.[37] A further study showed significant balance impairments combined with an unstable posture after administration of quazepam in test subjects.[38] An extensive review of the medical literature regarding the management of insomnia and the elderly found that there is considerable evidence of the effectiveness and durability of non-drug treatments for insomnia in adults of all ages and that these interventions are underutilized. Compared with the benzodiazepines including quazepam, the nonbenzodiazepine sedative/hypnotics appeared to offer few, if any, significant clinical advantages in efficacy or tolerability in elderly persons. It was found that newer agents with novel mechanisms of action and improved safety profiles, such as the melatonin agonists, hold promise for the management of chronic insomnia in elderly people. Long-term use of sedative/hypnotics for insomnia lacks an evidence base and has traditionally been discouraged for reasons that include concerns about such potential adverse drug effects as cognitive impairment (anterograde amnesia), daytime sedation, motor incoordination, and increased risk of motor vehicle accidents and falls. In addition, the effectiveness and safety of long-term use of these agents remain to be determined. It was concluded that more research is needed to evaluate the long-term effects of treatment and the most appropriate management strategy for elderly persons with chronic insomnia.[39]

Interactions

The absorption rate is likely to be significantly reduced if quazepam is taken in the fasted state reducing the hypnotic effect of quazepam. If 3 or more hours have passed since eating food then some food should be eaten before taking quazepam.[40][41]

Pharmacology

Quazepam is a trifluoroalkyl type of benzodiazepine. Quazepam is unique amongst benzodiazepines in that it selectively targets the GABAA α1 subunit receptors which are responsible for inducing sleep. Its mechanism of action is very similar to zolpidem and zaleplon in its pharmacology and can successfully substitute for zolpidem and zaleplon in animal studies.[42][43][44]

Quazepam is selective for type I benzodiazepine receptors containing the α1 subunit, similar to other drugs such as zaleplon and zolpidem. As a result, quazepam has little or no muscle relaxant properties. Most other benzodiazepines are unselective and bind to type1 GABAA receptors and type2 GABAA receptors. Type1 GABAA receptors include the α1 subunit containing GABAA receptors which are responsible for hypnotic properties of the drug. Type 2 receptors include the α2, α3 and α5 subunits which are responsible for anxiolytic action, amnesia and muscle relaxant properties.[45][46] Thus quazepam may have less side effects than other benzodiazepines but, it has a very long half-life of 25 hours which reduces its benefits as a hypnotic due to likely next day sedation. It also has two active metabolites with half-lives of 28 and 79 hours. Quazepam may also cause less drug tolerance than other benzodiazepines such as temazepam and triazolam perhaps due to its subtype selectivity.[47][48][49][50] The longer half-life of quazepam may have the advantage however, of causing less rebound insomnia than shorter acting subtype selective nonbenzodiazepines.[8][28] However, one of the major metabolites of quazepam, the N-desmethyl-2-oxoquazepam (aka N-desalkylflurazepam), binds unselectively to both type1 and type2 GABAA receptors. The N-desmethyl-2-oxoquazepam metabolite also has a very long half-life and likely contributes to the pharmacological effects of quazepam.[51]

Pharmacokinetics

Quazepam has an absorption half-life of 0.4 hours with a peak in plasma levels after 1.75 hours. It is eliminated both renally and through feces.[52] The active metabolites of quazepam are 2-oxoquazepam and N-desalkyl-2-oxoquazepam. The N-desalkyl-2-oxoquazepam metabolite has only limited pharmacological activity compared to the parent compound quazepam and the active metabolite 2-oxoquazepam. [citation needed] Quazepam and its major active metabolite 2-oxoquazepam both show high selectivity for the type1 GABAA receptors.[53][54][55][56] The elimination half-life range of quazepam is between 27 and 41 hours.[30]

Mechanism of action

Quazepam modulates specific GABAA receptors via the benzodiazepine site on the GABAA receptor. This modulation enhances the actions of GABA, causing an increase in opening frequency of the chloride ion channel which results in an increased influx of chloride ions into the GABAA receptors. Quazepam, unique amongst benzodiazepine drugs selectively targets type1 benzodiazepine receptors which results reduced sleep latency in promotion of sleep.[57][58][59] Quazepam also has some anticonvulsant properties.[60]

EEG and sleep

Quazepam has potent sleep inducing and sleep maintaining properties.[61][62] Studies in both animals and humans have demonstrated that EEG changes induced by quazepam resemble normal sleep patterns whereas other benzodiazepines disrupt normal sleep. Quazepam promotes slow wave sleep.[63][64] This positive effect of quazepam on sleep architecture may be due to its high selectivity for type1 benzodiazepine receptors as demonstrated in animal and human studies. This makes quazepam unique in the benzodiazepine family of drugs.[65][66]

Drug misuse

Quazepam is a drug with the potential for misuse. Two types of drug misuse can occur, either recreational misuse where the drug is taken to achieve a high, or when the drug is continued long term against medical advice.[67]

References

- ↑ US Patent 3845039

- ↑ "Evaluation of the safety and efficacy of quazepam for the treatment of insomnia in psychiatric outpatients". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 55 (2): 60–65. February 1994. PMID 7915708.

- ↑ "[Pharmacological profiles of benzodiazepinergic hypnotics and correlations with receptor subtypes]". Nihon Shinkei Seishin Yakurigaku Zasshi = Japanese Journal of Psychopharmacology 25 (3): 143–151. June 2005. PMID 16045197.

- ↑ "Pharmacological studies with quazepam, a new benzodiazepine hypnotic". Arzneimittel-Forschung 32 (11): 1456–1462. 1982. PMID 6129857.

- ↑ "The effect of a single dose of quazepam (Sch-16134) on the sleep of chronic insomniacs". The Journal of International Medical Research 7 (6): 583–587. 1979. doi:10.1177/030006057900700620. PMID 42593.

- ↑ (in en) Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. 2006. p. 538. ISBN 9783527607495. https://books.google.com/books?id=FjKfqkaKkAAC&pg=PA538.

- ↑ "Insomnia: drug treatment". Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore 20 (2): 269–272. March 1991. PMID 1679317.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Quazepam and temazepam: effects of short- and intermediate-term use and withdrawal". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 39 (3): 345–352. March 1986. doi:10.1038/clpt.1986.51. PMID 2868823.

- ↑ "Short-term study of quazepam 15 milligrams in the treatment of insomnia". The Journal of International Medical Research 11 (3): 162–166. 1983. doi:10.1177/030006058301100306. PMID 6347748.

- ↑ "Short-term quazepam treatment of insomnia in geriatric patients". Pharmatherapeutica 3 (4): 278–282. 1982. PMID 6128741.

- ↑ "Dose-response studies of quazepam". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 30 (2): 194–200. August 1981. doi:10.1038/clpt.1981.148. PMID 6113910.

- ↑ "Effects of quazepam as a preoperative night hypnotic: comparison with brotizolam". Journal of Anesthesia 21 (1): 7–12. 2007. doi:10.1007/s00540-006-0445-2. PMID 17285406.

- ↑ "The sedative-hypnotic properties of quazepam, a new hypnotic agent". Arzneimittel-Forschung 32 (11): 1452–1456. 1982. PMID 6129856.

- ↑ "Rebound insomnia and newer hypnotics". Psychopharmacology 108 (3): 248–255. 1992. doi:10.1007/BF02245108. PMID 1523276.

- ↑ "Respiratory effects of quazepam and pentobarbital". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 27 (4): 310–313. April 1987. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1987.tb03020.x. PMID 2890670.

- ↑ "Selective affinity of the benzodiazepines quazepam and 2-oxo-quazepam for BZ1 binding site and demonstration of 3H-2-oxo-quazepam as a BZ1 selective radioligand". Life Sciences 42 (2): 179–187. 1988. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(88)90681-9. PMID 2892106.

- ↑ "Relative affinity of quazepam for type-1 benzodiazepine receptors in brain". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 52 52 (Suppl): 15–20. September 1991. PMID 1680119.

- ↑ "Short-term treatment with quazepam of insomnia in geriatric patients". Clinical Therapeutics 5 (2): 174–178. 1982. PMID 6130842.

- ↑ "Evaluation of the short-term treatment of insomnia in out-patients with 15 milligrams of quazepam". The Journal of International Medical Research 11 (3): 155–161. 1983. doi:10.1177/030006058301100305. PMID 6347747.

- ↑ "Quazepam in the short-term treatment of insomnia in outpatients". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 44 (12): 454–456. December 1983. PMID 6361006.

- ↑ "Longitudinal study on pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of acute, steady-state and withdrawn quazepam". Arzneimittel-Forschung 39 (2): 276–283. February 1989. PMID 2567171.

- ↑ "FDA requiring Boxed Warning updated to improve safe use of benzodiazepine drug class". 23 September 2020. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-requiring-boxed-warning-updated-improve-safe-use-benzodiazepine-drug-class.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "Insomnia in generalized anxiety disorder: polysomnographic, psychometric and clinical investigations before, during and after therapy with a long- versus a short-half-life benzodiazepine (quazepam versus triazolam)". Neuropsychobiology 29 (2): 69–90. 1994. doi:10.1159/000119067. PMID 8170529.

- ↑ "Multiple-dose quazepam kinetics". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 35 (4): 520–524. April 1984. doi:10.1038/clpt.1984.70. PMID 6705450.

- ↑ "A comparative 25-night sleep laboratory study on the effects of quazepam and triazolam on chronic insomniacs". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 24 (2–3): 65–75. 1984. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1984.tb02767.x. PMID 6143767.

- ↑ "Comparison of short and long half-life benzodiazepine hypnotics: triazolam and quazepam". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 40 (4): 378–386. October 1986. doi:10.1038/clpt.1986.194. PMID 3530586.

- ↑ "[Controlled clinical study on the effect of quazepam versus triazolam in patients with sleep disorders]" (in it). Minerva Psichiatrica 30 (3): 159–164. 1989. PMID 2691808.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "[Recent progress in development of hypnotic drugs]" (in ja). Nihon Rinsho. Japanese Journal of Clinical Medicine 56 (2): 515–520. February 1998. PMID 9503861.

- ↑ "Quazepam and flurazepam: differential pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 52 52 (Suppl): 21–26. September 1991. PMID 1680120.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "Quazepam. A preliminary review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic efficacy in insomnia". Drugs 35 (1): 42–62. January 1988. doi:10.2165/00003495-198835010-00003. PMID 2894293.

- ↑ "Preclinical safety evaluation of the benzodiazepine quazepam". Arzneimittel-Forschung 37 (8): 906–913. August 1987. PMID 2890357.

- ↑ "Comparison of the effects of quazepam and triazolam on cognitive-neuromotor performance". Psychopharmacology 92 (4): 459–464. 1987. doi:10.1007/bf00176478. PMID 2888152.

- ↑ "Benzodiazepine dependence: focus on withdrawal syndrome". Annales Pharmaceutiques Françaises 67 (6): 408–413. November 2009. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2009.07.001. PMID 19900604.

- ↑ "Excretion of quazepam into human breast milk". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 24 (10): 457–462. October 1984. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1984.tb01819.x. PMID 6150944.

- ↑ "Quazepam kinetics in the elderly". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 36 (4): 566–569. October 1984. doi:10.1038/clpt.1984.220. PMID 6478742.

- ↑ "Objective measurements of daytime sleepiness and performance comparing quazepam with flurazepam in two adult populations using the Multiple Sleep Latency Test". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 52 52 (Suppl): 31–37. September 1991. PMID 1680123.

- ↑ "Comparison of hangover effects among triazolam, flunitrazepam and quazepam in healthy subjects: a preliminary report". Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 57 (3): 303–309. June 2003. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1819.2003.01121.x. PMID 12753571.

- ↑ "[Studies of time-course changes in human body balance after ingestion of long-acting hypnotics]" (in ja). Nihon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho 107 (2): 145–151. February 2004. doi:10.3950/jibiinkoka.107.145. PMID 15032004.

- ↑ "Management of chronic insomnia in elderly persons". The American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy 4 (2): 168–192. June 2006. doi:10.1016/j.amjopharm.2006.06.006. PMID 16860264.

- ↑ "Time effects of food intake on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of quazepam". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 55 (4): 382–388. April 2003. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01775.x. PMID 12680887.

- ↑ "Effects of foods on the pharmacokinetics and clinical efficacy of quazepam". Nihon Shinkei Seishin Yakurigaku Zasshi = Japanese Journal of Psychopharmacology 23 (5): 205–210. October 2003. PMID 14653226.

- ↑ "Discriminative stimulus effects of zolpidem in squirrel monkeys: role of GABA(A)/alpha1 receptors". Psychopharmacology 165 (3): 209–215. January 2003. doi:10.1007/s00213-002-1275-z. PMID 12420154.

- ↑ "Selective affinity of 1-N-trifluoroethyl benzodiazepines for cerebellar type 1 receptor sites". Life Sciences 35 (1): 105–113. July 1984. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(84)90157-7. PMID 6738302.

- ↑ "Use of the selective benzodiazepine-1 (BZ-1) ligand [3H]2-oxo-quazepam (SCH 15-725) to localize BZ-1 receptors in the rat brain". Neuroscience Letters 88 (1): 86–92. May 1988. doi:10.1016/0304-3940(88)90320-5. PMID 2899863.

- ↑ "Comparison of short- and long-acting benzodiazepine-receptor agonists with different receptor selectivity on motor coordination and muscle relaxation following thiopental-induced anesthesia in mice". Journal of Pharmacological Sciences 107 (3): 277–284. July 2008. doi:10.1254/jphs.FP0071991. PMID 18603831.

- ↑ "Binding sites for [3H]2-oxo-quazepam in the brain of the cat: evidence for heterogeneity of benzodiazepine recognition sites". Neuropharmacology 28 (7): 715–718. July 1989. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(89)90156-1. PMID 2569691.

- ↑ "Pharmacokinetics of benzodiazepines: metabolic pathways and plasma level profiles". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 8 8 (Suppl 4): 60–79. 1984. doi:10.1185/03007998409109545. PMID 6144464.

- ↑ "Quazepam: hypnotic efficacy and side effects". Pharmacotherapy 10 (1): 1–10; discussion 10–2. 1990. doi:10.1002/j.1875-9114.1990.tb02545.x. PMID 1969151.

- ↑ "Quazepam and flurazepam: long-term use and extended withdrawal". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 32 (6): 781–788. December 1982. doi:10.1038/clpt.1982.236. PMID 7140142.

- ↑ "Effect of sleep on quazepam kinetics". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 36 (1): 99–104. July 1984. doi:10.1038/clpt.1984.146. PMID 6734056.

- ↑ "Pharmacokinetics and drug interactions of the sedative hypnotics". Psychopharmacology Bulletin 37 (1): 10–29. 2003. doi:10.1007/BF01990373. PMID 14561946. http://www.medworksmedia.com/psychopharmbulletin/pdf/12/010-029_PB%20W03_Wang_final.pdf.

- ↑ "Disposition and metabolic fate of 14C-quazepam in man". Drug Metabolism and Disposition 13 (1): 25–29. 1985. PMID 2858372.

- ↑ "Enhancement of gamma-aminobutyric acid binding by quazepam, a benzodiazepine derivative with preferential affinity for type I benzodiazepine receptors". Journal of Neurochemistry 47 (2): 370–374. August 1986. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1986.tb04511.x. PMID 3016172.

- ↑ "Relationships of brain and plasma levels of quazepam, flurazepam, and their metabolites with pharmacological activity in mice". Life Sciences 39 (2): 161–168. July 1986. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(86)90451-0. PMID 3724367.

- ↑ "Preferential affinity of 3H-2-oxo-quazepam for type I benzodiazepine recognition sites in the human brain". Life Sciences 42 (2): 189–197. 1988. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(88)90682-0. PMID 2892107.

- ↑ "Benzodiazepine receptor binding of benzodiazepine hypnotics: receptor and ligand specificity". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior 43 (2): 413–416. October 1992. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(92)90170-K. PMID 1359574.

- ↑ "Benzodiazepine receptors and their relationship to the treatment of epilepsy". Epilepsia. 27 27 (Suppl 1): S3-13. 1986. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1986.tb05731.x. PMID 3017690.

- ↑ "Characterization of 3H-2-oxo-quazepam binding in the human brain". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry 12 (5): 701–712. 1988. doi:10.1016/0278-5846(88)90015-2. PMID 2906158.

- ↑ "Hypnotic effects of low doses of quazepam in older insomniacs". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 17 (5): 401–406. October 1997. doi:10.1097/00004714-199710000-00009. PMID 9315991.

- ↑ "Bidirectional effects of beta-carbolines in reflex epilepsy". Brain Research Bulletin 19 (3): 337–346. September 1987. doi:10.1016/0361-9230(87)90102-X. PMID 3119161.

- ↑ "Quazepam versus triazolam in patients with sleep disorders: a double-blind study". International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology Research 13 (3): 173–177. 1993. PMID 7901174.

- ↑ "Effects of the novel benzodiazepine agonist quazepam on suppressed behavior of monkeys". European Journal of Pharmacology 155 (1–2): 19–25. October 1988. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(88)90398-6. PMID 2907488.

- ↑ "Differential effects of benzodiazepines on EEG activity and hypnogenic mechanisms of the brain stem in cats". Archives Internationales de Pharmacodynamie et de Therapie 264 (2): 203–219. August 1983. PMID 6139096.

- ↑ "[Electroencephalographic study of Sch 161 (quazepam), a new benzodiazepine hypnotic, in rats and rabbits]" (in ja). Nihon Yakurigaku Zasshi. Folia Pharmacologica Japonica 90 (4): 221–238. October 1987. doi:10.1254/fpj.90.221. PMID 3428780.

- ↑ "Several new benzodiazepines selectively interact with a benzodiazepine receptor subtype". Neuroscience Letters 38 (1): 73–78. July 1983. doi:10.1016/0304-3940(83)90113-1. PMID 6136944.

- ↑ "Quazepam, a sedative-hypnotic selective for the benzodiazepine type 1 receptor: autoradiographic localization in rat and human brain". Clinical Neuropharmacology. 8 8 (Suppl 1): S26–S40. 1985. doi:10.1097/00002826-198508001-00005. PMID 2874881.

- ↑ "Relative abuse liability of hypnotic drugs: a conceptual framework and algorithm for differentiating among compounds". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 66 66 (Suppl 9): 31–41. 2005. PMID 16336040.

External links

- "Quazepam". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://druginfo.nlm.nih.gov/drugportal/name/quazepam.

|