Biology:Allopregnanolone

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Zulresso |

| Other names | brexanolone (USAN US) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a619037 |

| License data |

|

| Routes of administration | Intravenous[1] |

| Drug class | Neurosteroids; Antidepressants |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Oral: <5%[3] |

| Protein binding | >99%[1][3] |

| Metabolism | Non-CYP450 (keto-reduction via aldo-keto reductases (AKR), glucuronidation via glucuronosyltransferases (UGT), sulfation via sulfotransferases (SULT))[1][3] |

| Elimination half-life | 9 hours[1][3] |

| Excretion | Feces: 47%[1][3] Urine: 42%[1][3] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

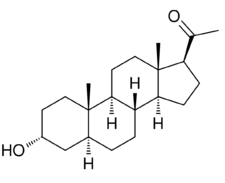

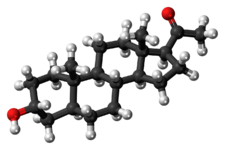

| Formula | C21H34O2 |

| Molar mass | 318.501 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Allopregnanolone is a naturally occurring neurosteroid which is made in the body from the hormone progesterone.[4][5] As a medication, allopregnanolone is referred to as brexanolone, sold under the brand name Zulresso,[1][6] and used to treat postpartum depression.[5][7][8] It is given by injection into a vein.[5][1]

Side effects of brexanolone may include sedation, sleepiness, dry mouth, hot flashes, and loss of consciousness.[1][5] It is a neurosteroid and acts as a positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor, the major biological target of the inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA).[1]

Brexanolone was approved for medical use in the United States in 2019.[5][9] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) considers it to be a first-in-class medication.[10] The long administration time, as well as the cost for a one-time treatment, have raised concerns about accessibility for many women.[11]

Medical uses

Brexanolone is used to treat postpartum depression in adult women, administered as a continuous intravenous infusion over a period of 60 hours.[5][12]

Clinical efficacy

Women experiencing moderate to severe postpartum depression when treated with a single dose of intravenous brexanolone display a significant reduction in HAM-D scores and this improvement was still observed 30 days post-treatment.[13]

Side effects

Side effects of brexanolone include dizziness (10–20%), sedation (13–21%), headache (18%), nausea (10%), dry mouth (3–11%), loss of consciousness (3–5%), and flushing (2–5%).[1][5][3][14] It can produce euphoria to a degree similar to that of alprazolam (3–13% at infusion doses of 90–270 μg over a one-hour period).[1] Serious or severe adverse effects are rare but may include altered state of consciousness, syncope, presyncope, fatigue, and insomnia.[14]

Biological function

Allopregnanolone possesses a wide variety of effects, including, in no particular order, antidepressant, anxiolytic, stress-reducing, rewarding,[15] prosocial,[16] antiaggressive,[17] prosexual,[16] sedative, pro-sleep,[18] cognitive, memory-impairment, analgesic,[19] anesthetic, anticonvulsant, neuroprotective, and neurogenic effects.[4] Fluctuations in the levels of allopregnanolone and the other neurosteroids seem to play an important role in the pathophysiology of mood, anxiety, premenstrual syndrome, catamenial epilepsy, and various other neuropsychiatric conditions.[20][21][22]

During pregnancy, allopregnanolone and pregnanolone are involved in sedation and anesthesia of the fetus.[23][24]

Allopregnanolone is a metabolic intermediate in an androgen backdoor pathway from progesterone to dihydrotestosterone, which occurs during normal male fetus development; placental progesterone in the male fetus is the feedstock of this pathway; deficiencies in this pathway lead to insufficient virilization of the male fetus.[25]

Mechanism of action

Molecular interactions

Allopregnanolone is an endogenous inhibitory pregnane neurosteroid.[4] It is made from pregnenolone, and is a positive allosteric modulator of the action of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) at GABAA receptor.[4] Allopregnanolone has effects similar to those of other positive allosteric modulators of the GABA action at GABAA receptor such as the benzodiazepines, including anxiolytic, sedative, and anticonvulsant activity.[4][26][27] Endogenously produced allopregnanolone exerts a neurophysiological role by fine-tuning of GABAA receptor and modulating the action of several positive allosteric modulators and agonists at GABAA receptor.[28]

Allopregnanolone acts as a highly potent positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor.[4] While allopregnanolone, like other inhibitory neurosteroids such as THDOC, positively modulates all GABAA receptor isoforms, those isoforms containing δ subunits exhibit the greatest potentiation.[29] Allopregnanolone has also been found to act as a positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA-ρ receptor, though the implications of this action are unclear.[30][31] In addition to its actions on GABA receptors, allopregnanolone, like progesterone, is known to be a negative allosteric modulator of nACh receptors,[32] and also appears to act as a negative allosteric modulator of the 5-HT3 receptor.[33] Along with the other inhibitory neurosteroids, allopregnanolone appears to have little or no action at other ligand-gated ion channels, including the NMDA, AMPA, kainate, and glycine receptors.[34]

Unlike progesterone, allopregnanolone is inactive at the classical nuclear progesterone receptor (PR).[34] However, allopregnanolone can be intracellularly oxidized into 5α-dihydroprogesterone, which does act as an agonist of the PR, and for this reason, allopregnanolone can produce PR-mediated progestogenic effects.[35][36] (5α-dihydroprogesterone is reduced to produce allopregnanolone, and progesterone is reduced to produce 5α-dihydroprogesterone). In addition, allopregnanolone was reported in 2012 to be an agonist of the membrane progesterone receptors (mPRs) discovered shortly before, including mPRδ, mPRα, and mPRβ, with its activity at these receptors about a magnitude more potent than at the GABAA receptor.[37][38] The action of allopregnanolone at these receptors may be related, in part, to its neuroprotective and antigonadotropic properties.[37][39] Also like progesterone, recent evidence has shown that allopregnanolone is an activator of the pregnane X receptor.[34][40]

Similarly to many other GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators, allopregnanolone has been found to act as an inhibitor of L-type voltage-gated calcium channels (L-VGCCs),[41] including α1 subtypes Cav1.2 and Cav1.3.[42] However, the threshold concentration of allopregnanolone to inhibit L-VGCCs was determined to be 3 μM (3,000 nM), which is far greater than the concentration of 5 nM that has been estimated to be naturally produced in the human brain.[42] Thus, inhibition of L-VGCCs is unlikely of any actual significance in the effects of endogenous allopregnanolone.[42] Also, allopregnanolone, along with several other neurosteroids, has been found to activate the G protein-coupled bile acid receptor (GPBAR1, or TGR5).[43] However, it is only able to do so at micromolar concentrations, which, similarly to the case of the L-VGCCs, are far greater than the low nanomolar concentrations of allopregnanolone estimated to be present in the brain.[43]

Biphasic actions at the GABAA receptor

Increased levels of allopregnanolone can produce paradoxical effects, including negative mood, anxiety, irritability, and aggression.[44][45][46] This appears to be because allopregnanolone possesses biphasic, U-shaped actions at the GABAA receptor – moderate level increases (in the range of 1.5–2 nmol/L total allopregnanolone, which are approximately equivalent to luteal phase levels) inhibit the activity of the receptor, while lower and higher concentration increases stimulate it.[44][45] This seems to be a common effect of many GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators.[20][46] In accordance, acute administration of low doses of micronized progesterone (which reliably elevates allopregnanolone levels) has been found to have negative effects on mood, while higher doses have a neutral effect.[47]

Antidepressant effects

The mechanism by which neurosteroid GABAA receptor PAMs like brexanolone have antidepressant effects is unknown.[48] Other GABAA receptor PAMs, such as benzodiazepines, are not thought of as antidepressants and have no proven efficacy,[48] although alprazolam has historically been prescribed for depression.[49][50] Neurosteroid GABAA receptor PAMs are known to interact with GABAA receptors and subpopulations differently than benzodiazepines.[48] GABAA receptor-potentiating neurosteroids may preferentially target δ-subunit–containing GABAA receptors, and enhance both tonic and phasic inhibition mediated by GABAA receptors.[48] It is possible that neurosteroids like allopregnanolone may act on other targets, including membrane progesterone receptors, T-type voltage-gated calcium channels, and others, to mediate antidepressant effects.[48]

Pharmacology

Pharmacokinetics

Brexanolone has low oral bioavailability of less than 5%, necessitating non-oral administration.[3] The volume of distribution of brexanolone is approximately 3 L/kg.[3] Its plasma protein binding is more than 99%.[1][3] Brexanolone is metabolized by keto-reduction mediated via aldo-keto reductases.[1][3] The compound is conjugated by glucuronidation via glucuronosyltransferases and sulfation via sulfotransferases.[1] It is not metabolized significantly by the cytochrome P450 system.[1][3] The three main metabolites of brexanolone are inactive.[3] The elimination half-life of brexanolone is nine hours.[1][3] Its total plasma clearance is 1 L/h/kg.[3] It is excreted 47% in feces and 42% in urine.[1][3] Less than 1% is excreted as unchanged brexanolone.[3]

Chemistry

Allopregnanolone is a pregnane (C21) steroid and is also known as 5α-pregnan-3α-ol-20-one, 5α-pregnane-3α-ol-20-one,[51][52][53][54][55] 3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one, or 3α,5α-tetrahydroprogesterone (3α,5α-THP). It is closely related structurally to 5-pregnenolone (pregn-5-en-3β-ol-20-dione), progesterone (pregn-4-ene-3,20-dione), the isomers of pregnanedione (5-dihydroprogesterone; 5-pregnane-3,20-dione), the isomers of 4-pregnenolone (3-dihydroprogesterone; pregn-4-en-3-ol-20-one), and the isomers of pregnanediol (5-pregnane-3,20-diol). In addition, allopregnanolone is one of four isomers of pregnanolone (3,5-tetrahydroprogesterone), with the other three isomers being pregnanolone (5β-pregnan-3α-ol-20-one), isopregnanolone (5α-pregnan-3β-ol-20-one), and epipregnanolone (5β-pregnan-3β-ol-20-one).

Biosynthesis

The biosynthesis of allopregnanolone in the brain starts with the conversion of progesterone into 5α-dihydroprogesterone by 5α-reductase. After that, 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase converts this intermediate into allopregnanolone.[4] Allopregnanolone in the brain is produced by cortical and hippocampus pyramidal neurons and pyramidal-like neurons of the basolateral amygdala.[56]

Derivatives

A variety of synthetic derivatives and analogues of allopregnanolone with similar activity and effects exist, including alfadolone (3α,21-dihydroxy-5α-pregnane-11,20-dione), alfaxolone (3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnane-11,20-dione), ganaxolone (3α-hydroxy-3β-methyl-5α-pregnan-20-one), hydroxydione (21-hydroxy-5β-pregnane-3,20-dione), minaxolone (11α-(dimethylamino)-2β-ethoxy-3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one), Org 20599 (21-chloro-3α-hydroxy-2β-morpholin-4-yl-5β-pregnan-20-one), Org 21465 (2β-(2,2-dimethyl-4-morpholinyl)-3α-hydroxy-11,20-dioxo-5α-pregnan-21-yl methanesulfonate), and renanolone (3α-hydroxy-5β-pregnan-11,20-dione).

The 21-hydroxylated derivative of this compound, tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone, is an endogenous inhibitory neurosteroid with similar properties to those of allopregnanolone, and the 3β-methyl analogue of allopregnanolone, ganaxolone, is under development to treat epilepsy and other conditions, including post-traumatic stress disorder.[4]

History

In March 2019, brexanolone was approved in the United States for the treatment of postpartum depression (PPD) in adult women,[5][9] the first drug approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) specifically for PPD.[5]

The efficacy of brexanolone was shown in two clinical studies of participants who received a 60-hour continuous intravenous infusion of brexanolone or placebo and were then followed for four weeks.[5] The FDA approved allopregnanolone based on evidence from three clinical trials, conducted in the United States, (Trial 1/NCT02942004, Trial 3/NCT02614541, Trial 2/ NCT02942017) of 247 women with moderate or severe postpartum depression.[57]

The FDA granted the application for brexanolone priority review and breakthrough therapy designations, and granted approval of Zulresso to Sage Therapeutics, Inc.[5]

Society and culture

Names

Allopregnanolone is the name of the molecule commonly used in the literature when it is discussed as an endogenous neurosteroid.[citation needed] Brexanolone is both the International Nonproprietary Name and the United States Adopted Name in the context of its use as a medication.[58][59]

Zulresso is a brand name of the medication.[1]

Legal status

In the United States, brexanolone is a Schedule IV controlled substance.[2][1]

Available forms

Brexanolone is an aqueous mixture of synthetic allopregnanolone and sulfobutyl ether β-cyclodextrin (betadex sulfobutyl ether sodium), a solubilizing agent.[1][3] It is provided at an allopregnanolone concentration of 100 mg/20 mL (5 mg/mL) in single-dose vials for use by intravenous infusion.[1] Each mL of brexanolone solution contains 5 mg allopregnanolone, 250 mg sulfobutyl ether β-cyclodextrin, 0.265 mg citric acid monohydrate, 2.57 mg sodium citrate dihydrate, and water for injection.[1] The solution is hypertonic and must be diluted to a target concentration of 1 mg/mL with sterile water and sodium chloride prior to administration.[1] Five infusion bags are generally required for the full infusion.[1] More than five infusion bags are necessary for patients weighing more than 90 kg (200 lbs).[1]

Research

Brexanolone was under development as an intravenously administered medication for the treatment of major depressive disorder, super-refractory status epilepticus, and essential tremor, but development for these indications was discontinued.[60]

It has been suggested that allopregnanolone and its precursor pregnenolone may have therapeutic potential for treatment of various symptoms of alcohol use disorders by restoring deficits in GABAergic inhibition, moderating corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) signaling, and inhibiting excessive neuroimmune activation. Many co-occurring symptoms of ethanol addiction (e.g., anxiety, depression, seizures, sleep disturbance, pain) that are believed to contribute to the downward spiral of the addiction may also be controlled with neuroactive steroids.[61]

Exogenous progesterone, such as oral progesterone, elevates allopregnanolone levels in the body with good dose-to-serum level correlations.[62] Due to this, it has been suggested that oral progesterone could be described as a prodrug of sorts for allopregnanolone.[62] As a result, there has been some interest in using oral progesterone to treat catamenial epilepsy,[63] as well as other menstrual cycle-related and neurosteroid-associated conditions. In addition to oral progesterone, oral pregnenolone has also been found to act as a prodrug of allopregnanolone,[64][65][66] though also of pregnenolone sulfate.[67]

In animal models of traumatic brain injury, allopregnanolone has been shown to reduce inflammation by attenuating the production of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β and TNF-α) at 3 h after the injury. It has also been shown to reduce the severity of brain damage and improve cognitive function and recovery.[68]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 "Zulresso- brexanolone injection, solution". 18 November 2019. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=b40f3b2a-1859-4ed6-8551-444300806d13.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "DEA Schedules Postpartum Depression Treatment Zulresso". 17 June 2019. https://www.empr.com/home/news/dea-schedules-postpartum-depression-treatment-zulresso/.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 "Brexanolone: First Global Approval". Drugs 79 (7): 779–783. May 2019. doi:10.1007/s40265-019-01121-0. PMID 31006078.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 "Neurosteroids". Sex Differences in the Human Brain, their Underpinnings and Implications. Progress in Brain Research. 186. Elsevier. 2010. pp. 113–137. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53630-3.00008-7. ISBN 9780444536303.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 "FDA approves first treatment for post-partum depression". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 19 March 2019. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "ChemIDplus - 516-54-1 - AURFZBICLPNKBZ-SYBPFIFISA-N - Brexanolone [USAN - Similar structures search, synonyms, formulas, resource links, and other chemical information."]. NIH Toxnet. https://chem.nlm.nih.gov/chemidplus/rn/516-54-1.

- ↑ "Pharmacotherapy of Postpartum Depression: Current Approaches and Novel Drug Development". CNS Drugs 33 (3): 265–282. March 2019. doi:10.1007/s40263-019-00605-7. PMID 30790145.

- ↑ "A new generation of antidepressants: an update on the pharmaceutical pipeline for novel and rapid-acting therapeutics in mood disorders based on glutamate/GABA neurotransmitter systems". Drug Discovery Today 24 (2): 606–615. February 2019. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2018.11.007. PMID 30447328.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Drug Approval Package: Zulresso". 7 February 2019. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2019/211371Orig1s000TOC.cfm.

- ↑ "New Drug Therapy Approvals 2019". 31 December 2019. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/new-drugs-fda-cders-new-molecular-entities-and-new-therapeutic-biological-products/new-drug-therapy-approvals-2019.

- ↑ "New Postpartum Depression Drug Could Be Hard To Access For Moms Most In Need". NPR. 21 March 2019. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/03/21/705545014/new-postpartum-depression-drug-could-be-hard-to-access-for-moms-most-in-need.

- ↑ "Zulresso (brexanolone) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". https://reference.medscape.com/drug/zulresso-brexanolone-1000299.

- ↑ "Brexanolone, a GABAA Modulator, in the Treatment of Postpartum Depression in Adults: A Comprehensive Review". Frontiers in Psychiatry 12: 699740. 2021. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.699740. PMID 34594247.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Review of Allopregnanolone Agonist Therapy for the Treatment of Depressive Disorders" (in English). Drug Design, Development and Therapy 15: 3017–3026. 2021-07-09. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S240856. PMID 34267503.

- ↑ "The neurosteroid allopregnanolone increases dopamine release and dopaminergic response to morphine in the rat nucleus accumbens". The European Journal of Neuroscience 16 (1): 169–173. July 2002. doi:10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02084.x. PMID 12153544.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Neurosteroids' effects and mechanisms for social, cognitive, emotional, and physical functions". Psychoneuroendocrinology 34 (Suppl 1): S143–S161. December 2009. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.07.005. PMID 19656632.

- ↑ "Changes in brain testosterone and allopregnanolone biosynthesis elicit aggressive behavior". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102 (6): 2135–2140. February 2005. doi:10.1073/pnas.0409643102. PMID 15677716. Bibcode: 2005PNAS..102.2135P.

- ↑ "Steroid hormones and sleep regulation". Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry 12 (11): 1040–1048. October 2012. doi:10.2174/138955712802762167. PMID 23092405.

- ↑ "Potential role of allopregnanolone for a safe and effective therapy of neuropathic pain". Progress in Neurobiology 113: 70–78. February 2014. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.07.004. PMID 23948490.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Pathogenesis in menstrual cycle-linked CNS disorders". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1007 (1): 42–53. December 2003. doi:10.1196/annals.1286.005. PMID 14993039. Bibcode: 2003NYASA1007...42B.

- ↑ "The role of sex steroids in catamenial epilepsy and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: implications for diagnosis and treatment". Epilepsy & Behavior 13 (1): 12–24. July 2008. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.02.004. PMID 18346939.

- ↑ "Female reproductive steroids and neuronal excitability". Neurological Sciences 32 (Suppl 1): S31–S35. May 2011. doi:10.1007/s10072-011-0532-5. PMID 21533709.

- ↑ "The importance of 'awareness' for understanding fetal pain". Brain Research. Brain Research Reviews 49 (3): 455–471. November 2005. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.01.006. PMID 16269314.

- ↑ "The emergence of human consciousness: from fetal to neonatal life". Pediatric Research 65 (3): 255–260. March 2009. doi:10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181973b0d. PMID 19092726. "[...] the fetus is sedated by the low oxygen tension of the fetal blood and the neurosteroid anesthetics pregnanolone and the sleep-inducing prostaglandin D2 provided by the placenta (36).".

- ↑ "Alternative androgen pathways". WikiJournal of Medicine 10: X. 2023. doi:10.15347/WJM/2023.003.

- ↑ "Neurosteroids — Endogenous Regulators of Seizure Susceptibility and Role in the Treatment of Epilepsy". Jasper's Basic Mechanisms of the Epilepsies, 4th Edition: 984–1002. 2012. doi:10.1093/med/9780199746545.003.0077. ISBN 9780199746545. PMID 22787590.

- ↑ "Anticonvulsant activity of neurosteroids: correlation with gamma-aminobutyric acid-evoked chloride current potentiation". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 270 (3): 1223–1229. September 1994. PMID 7932175.

- ↑ "Brain allopregnanolone regulates the potency of the GABA(A) receptor agonist muscimol". Neuropharmacology 39 (3): 440–448. January 2000. doi:10.1016/S0028-3908(99)00149-5. PMID 10698010.

- ↑ "Rapid Throughput Analysis of GABAA Receptor Subtype Modulators and Blockers Using DiSBAC1(3) Membrane Potential Red Dye". Molecular Pharmacology 92 (1): 88–99. July 2017. doi:10.1124/mol.117.108563. PMID 28428226.

- ↑ "Differential modulation of the gamma-aminobutyric acid type C receptor by neuroactive steroids". Molecular Pharmacology 56 (4): 752–759. October 1999. PMID 10496958.

- ↑ "Neuroactive steroids and human recombinant rho1 GABAC receptors". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 323 (1): 236–247. October 2007. doi:10.1124/jpet.107.127365. PMID 17636008.

- ↑ "Neurosteroids modulate nicotinic receptor function in mouse striatal and thalamic synaptosomes". Journal of Neurochemistry 68 (6): 2412–2423. June 1997. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68062412.x. PMID 9166735.

- ↑ "Functional antagonism of gonadal steroids at the 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptor". Molecular Endocrinology 12 (9): 1441–1451. September 1998. doi:10.1210/mend.12.9.0163. PMID 9731711.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 "Neurosteroid regulation of central nervous system development". Pharmacology & Therapeutics 116 (1): 107–124. October 2007. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.04.011. PMID 17651807.

- ↑ "Progesterone receptor-mediated effects of neuroactive steroids". Neuron 11 (3): 523–530. September 1993. doi:10.1016/0896-6273(93)90156-l. PMID 8398145.

- ↑ "Clinical Potential of Neurosteroids for CNS Disorders". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 37 (7): 543–561. July 2016. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2016.04.003. PMID 27156439.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 "Membrane progesterone receptors: evidence for neuroprotective, neurosteroid signaling and neuroendocrine functions in neuronal cells". Neuroendocrinology 96 (2): 162–171. 2012. doi:10.1159/000339822. PMID 22687885.

- ↑ "Characterization, neurosteroid binding and brain distribution of human membrane progesterone receptors δ and {epsilon} (mPRδ and mPR{epsilon}) and mPRδ involvement in neurosteroid inhibition of apoptosis". Endocrinology 154 (1): 283–295. January 2013. doi:10.1210/en.2012-1772. PMID 23161870.

- ↑ "Progesterone receptor A (PRA) and PRB-independent effects of progesterone on gonadotropin-releasing hormone release". Endocrinology 150 (8): 3833–3844. August 2009. doi:10.1210/en.2008-0774. PMID 19423765.

- ↑ "PXR (NR1I2): splice variants in human tissues, including brain, and identification of neurosteroids and nicotine as PXR activators". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 199 (3): 251–265. September 2004. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2003.12.027. PMID 15364541.

- ↑ "Inhibition of evoked glutamate release by neurosteroid allopregnanolone via inhibition of L-type calcium channels in rat medial prefrontal cortex". Neuropsychopharmacology 32 (7): 1477–1489. July 2007. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301261. PMID 17151597.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 "Inhibition of recombinant L-type voltage-gated calcium channels by positive allosteric modulators of GABAA receptors". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 337 (1): 301–311. April 2011. doi:10.1124/jpet.110.178244. PMID 21262851.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 "The bile acid receptor TGR5 (Gpbar-1) acts as a neurosteroid receptor in brain". Glia 58 (15): 1794–1805. November 2010. doi:10.1002/glia.21049. PMID 20665558.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 "Paradoxical effects of GABA-A modulators may explain sex steroid induced negative mood symptoms in some persons". Neuroscience 191: 46–54. September 2011. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.03.061. PMID 21600269.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 "Sex steroid induced negative mood may be explained by the paradoxical effect mediated by GABAA modulators". Psychoneuroendocrinology 34 (8): 1121–1132. September 2009. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.02.003. PMID 19272715.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 "Allopregnanolone and mood disorders". Progress in Neurobiology 113: 88–94. February 2014. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.07.005. PMID 23978486.

- ↑ "Allopregnanolone concentration and mood--a bimodal association in postmenopausal women treated with oral progesterone". Psychopharmacology 187 (2): 209–221. August 2006. doi:10.1007/s00213-006-0417-0. PMID 16724185.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 48.3 48.4 "Neurosteroids as novel antidepressants and anxiolytics: GABA-A receptors and beyond". Neurobiology of Stress 11: 100196. November 2019. doi:10.1016/j.ynstr.2019.100196. PMID 31649968.

- ↑ "Alprazolam as an antidepressant". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 49 (4): 148–150. April 1988. PMID 3281931.

- ↑ "Alprazolam and standard antidepressants in the treatment of depression: a meta-analysis of the antidepressant effect". Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand = Chotmaihet Thangphaet (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (UK)) 80 (3): 183–188. March 1997. PMID 9175386. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK67062/.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs nameddoi1010970000054219900900100702 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedpmid697360 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedpmid9038248 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedpmid12175598 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedpmid15249131 - ↑ "Characterization of brain neurons that express enzymes mediating neurosteroid biosynthesis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103 (39): 14602–14607. September 2006. doi:10.1073/pnas.0606544103. PMID 16984997. Bibcode: 2006PNAS..10314602A.

- ↑ "Drug Trials Snapshots: Zulresso". 2 April 2019. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/drug-trials-snapshots-zulresso.

- ↑ "INN Brexanolone". https://mednet-communities.net/inn/db/ViewINN.aspx?i=10446.

- ↑ "KEGG DRUG: Brexanolone". https://www.genome.jp/dbget-bin/www_bget?dr:D11149.

- ↑ "Brexanolone - Sage Therapeutics". AdisInsight. http://adisinsight.springer.com/drugs/800039944.

- ↑ "A Rationale for Allopregnanolone Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorders: Basic and Clinical Studies". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 44 (2): 320–339. February 2020. doi:10.1111/acer.14253. PMID 31782169.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 "Pharmacokinetics of progesterone and its metabolites allopregnanolone and pregnanolone after oral administration of low-dose progesterone". Maturitas 54 (3): 238–244. June 2006. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.11.005. PMID 16406399.

- ↑ Complementary and Alternative Therapies for Epilepsy. Demos Medical Publishing. 1 January 2005. pp. 378–. ISBN 978-1-934559-08-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=WVUE-6Xdny4C&pg=PT378.

- ↑ "Urinary marker of oral pregnenolone administration". Steroids 70 (3): 179–183. March 2005. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2004.12.007. PMID 15763596.

- ↑ "Investigations on changes in ¹³C/¹²C ratios of endogenous urinary steroids after pregnenolone administration". Drug Testing and Analysis 3 (5): 283–290. May 2011. doi:10.1002/dta.281. PMID 21538944.

- ↑ "Allopregnanolone elevations following pregnenolone administration are associated with enhanced activation of emotion regulation neurocircuits". Biological Psychiatry 73 (11): 1045–1053. June 2013. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.12.008. PMID 23348009.

- ↑ "Brain distribution and behavioral effects of progesterone and pregnenolone after intranasal or intravenous administration". European Journal of Pharmacology 641 (2–3): 128–134. September 2010. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.05.033. PMID 20570588.

- ↑ "Progesterone and allopregnanolone reduce inflammatory cytokines after traumatic brain injury". Experimental Neurology 189 (2): 404–412. October 2004. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.06.008. PMID 15380490.

Further reading

- "Neurosteroid modulation of synaptic and extrasynaptic GABA(A) receptors". Pharmacology & Therapeutics 116 (1): 20–34. October 2007. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.03.007. PMID 17531325.

- "Neurosteroids as novel antidepressants and anxiolytics: GABA-A receptors and beyond". Neurobiology of Stress 11: 100196. November 2019. doi:10.1016/j.ynstr.2019.100196. PMID 31649968.

External links

- Clinical trial number NCT02942004 for "A Study to Evaluate Efficacy and Safety of SAGE-547 in Participants With Severe Postpartum Depression (547-PPD-202B)" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- Clinical trial number NCT02614547 for "A Study to Evaluate SAGE-547 in Patients With Severe Postpartum Depression" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- Clinical trial number NCT02942017 for "A Study to Evaluate Safety and Efficacy of SAGE-547 in Participants With Moderate Postpartum Depression (547-PPD-202C)" at ClinicalTrials.gov

|