Biology:Flutamide

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Eulexin, others |

| Other names | Niftolide; SCH-13521; 4'-Nitro-3'-trifluoromethyl-isobutyranilide |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a697045 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Nonsteroidal antiandrogen |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Complete (>90%)[1] |

| Protein binding | Flutamide: 94–96%[1] Hydroxyflutamide: 92–94%[1] |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP1A2)[7][3] |

| Metabolites | Hydroxyflutamide[2][3] |

| Elimination half-life | Flutamide: 5–6 hours[4][3] Hydroxyflutamide: 8–10 hours[5][6][3][1] |

| Excretion | Urine (mainly)[1] Feces (4.2%)[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

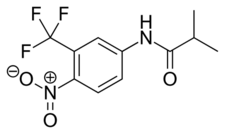

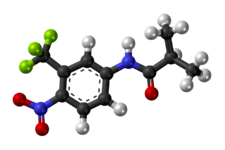

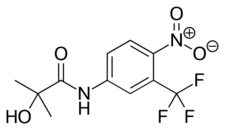

| Formula | C11H11F3N2O3 |

| Molar mass | 276.215 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 111.5 to 112.5 °C (232.7 to 234.5 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Flutamide, sold under the brand name Eulexin among others, is a nonsteroidal antiandrogen (NSAA) which is used primarily to treat prostate cancer.[8][9] It is also used in the treatment of androgen-dependent conditions like acne, excessive hair growth, and high androgen levels in women.[10] It is taken by mouth, usually three times per day.[11]

Side effects in men include breast tenderness and enlargement, feminization, sexual dysfunction, and hot flashes. Conversely, the medication has fewer side effects and is better-tolerated in women with the most common side effect being dry skin. Diarrhea and elevated liver enzymes can occur in both sexes. Rarely, flutamide can cause liver damage, lung disease, sensitivity to light, elevated methemoglobin, elevated sulfhemoglobin, and deficient neutrophils.[12][13][14][15] Numerous cases of liver failure and death have been reported, which has limited the use of flutamide.[12]

Flutamide acts as a selective antagonist of the androgen receptor (AR), competing with androgens like testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) for binding to ARs in tissues like the prostate gland. By doing so, it prevents their effects and stops them from stimulating prostate cancer cells to grow. Flutamide is a prodrug to a more active form. Flutamide and its active form stay in the body for a relatively short time, which makes it necessary to take flutamide multiple times per day.[citation needed]

Flutamide was first described in 1967 and was first introduced for medical use in 1983.[16] It became available in the United States in 1989. The medication has largely been replaced by newer and improved NSAAs, namely bicalutamide and enzalutamide, due to their better efficacy, tolerability, safety, and dosing frequency (once per day), and is now relatively little-used.[4][17] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[18]

Medical uses

Prostate cancer

GnRH is released by the hypothalamus in a pulsatile fashion; this causes the anterior pituitary gland to release luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). LH stimulates the testes to produce testosterone, which is metabolized to DHT by the enzyme 5α-reductase.[citation needed]

DHT, and to a significantly smaller extent, testosterone, stimulate prostate cancer cells to grow. Therefore, blocking these androgens can provide powerful treatment for prostate cancer, especially metastatic disease. Normally administered are GnRH analogues, such as leuprorelin or cetrorelix. Although GnRH agonists stimulate the same receptors that GnRH does, since they are present continuously and not in a pulsatile manner, they serve to inhibit the pituitary gland and therefore block the whole chain. However, they initially cause a surge in activity; this is not solely a theoretical risk but may cause the cancer to flare. Flutamide was initially used at the beginning of GnRH agonist therapy to block this surge, and it and other NSAAs continue in this use. In contrast to GnRH agonists, GnRH antagonists don't cause an initial androgen surge, and are gradually replacing GnRH agonists in clinical use.[citation needed]

There have been studies to investigate the benefit of adding an antiandrogen to surgical orchiectomy or its continued use with a GnRH analogue (combined androgen blockade (CAB)). Adding antiandrogens to orchiectomy showed no benefit, while a small benefit was shown with adding antiandrogens to GnRH analogues.[citation needed]

Unfortunately, therapies which lower testosterone levels, such as orchiectomy or GnRH analogue administration, also have significant side effects. Compared to these therapies, treatment with antiandrogens exhibits "fewer hot flashes, less of an effect on libido, less muscle wasting, fewer personality changes, and less bone loss." However, antiandrogen therapy alone is less effective than surgery. Nevertheless, given the advanced age of many with prostate cancer, as well as other features, many men may choose antiandrogen therapy alone for a better quality of life.[19]

Flutamide has been found to be similarly effective in the treatment of prostate cancer to bicalutamide, although indications of inferior efficacy, including greater compensatory increases in testosterone levels and greater reductions in PSA levels with bicalutamide, were observed.[20][21] The medication, at a dosage of 750 mg/day (250 mg three times daily), has also been found to be equivalent in effectiveness to 250 mg/day oral cyproterone acetate as a monotherapy in the treatment of prostate cancer in a large-scale clinical trial of 310 patients, though its side effect and toxicity profiles (including gynecomastia, diarrhea, nausea, loss of appetite, and liver disturbances) were regarded as considerably worse than those of cyproterone acetate.[22]

A dosage of 750 mg/day flutamide (250 mg/three times a day) is roughly equivalent in terms of effectiveness to 50 mg/day bicalutamide when used as the antiandrogen component in combined androgen blockade in the treatment of advanced prostate cancer.[23]

Flutamide has been used to prevent the effects of the testosterone flare at the start of GnRH agonist therapy in men with prostate cancer.[24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][excessive citations]

The combination of flutamide with an estrogen such as ethinylestradiol sulfonate has been used as a form of combined androgen blockade and as an alternative to the combination of flutamide with surgical or medical castration.[32]

Skin and hair conditions

Flutamide has been researched and used extensively in the treatment of androgen-dependent skin and hair conditions in women including acne, seborrhea, hirsutism, and scalp hair loss, as well as in hyperandrogenism (e.g., in polycystic ovary syndrome or congenital adrenal hyperplasia), and is effective in improving the symptoms of these conditions. The dosages used are lower than those used in the treatment of prostate cancer. Although flutamide continues to be used for these indications, its use in recent years has been limited due to the risk of potentially fatal hepatotoxicity, and it is no longer recommended as a first- or second-line therapy.[33][34][35][36] The related NSAA bicalutamide has also been found to be effective in the treatment of hirsutism in women and appears to have comparable effectiveness to that of flutamide,[37][38][39] but has a far lower and only small risk of hepatotoxicity in comparison.[40][41][42]

Aside from its risk of liver toxicity and besides other nonsteroidal antiandrogens, it has been said that flutamide is likely the best typically used antiandrogen medication for the treatment of androgen-dependent symptoms in women.[43] This is related to its high effectiveness and minimal side effects.[43]

Acne and seborrhea

Flutamide has been found to be effective in the treatment of acne and seborrhea in women in a number of studies.[44][45] In a long-term study of 230 women with acne, 211 of whom also had seborrhea, very-low-dose flutamide alone or in combination with an oral contraceptive caused a marked decrease in acne and seborrhea after 6 months of treatment, with maximal effect by 1 year of treatment and benefits maintained in the years thereafter.[44][46] In the study, 97% of the women reported satisfaction with the control of their acne with flutamide.[47] In another study, flutamide decreased acne and seborrhea scores by 80% in only 3 months.[48][2] In contrast, spironolactone decreased symptoms by only 40% in the same time period, suggesting superior effectiveness for flutamide for these indications.[48][49] Flutamide has, in general, been found to reduce symptoms of acne by as much as 90% even at low doses, with several studies showing complete acne clearance.[45][50][2]

Excessive hair growth

Flutamide has been found to be effective in the treatment of hirsutism (excessive body/facial hair growth) in numerous studies.[33][51][37] It possesses moderate effectiveness for this indication, and the overall quality of the evidence is considered to be moderate.[51][33] The medication shows equivalent or superior effectiveness to other antiandrogens including spironolactone, cyproterone acetate, and finasteride in the treatment of hirsutism, although its relatively high risk of hepatotoxicity makes it unfavorable compared to these other options.[2][33] It has been used to treat hirsutism at dosages ranging from 62.5 mg/day to 750 mg/day.[43] A study found that multiple dosages of flutamide significantly reduced hirsutism in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and that there were no significant differences in the effectiveness for dosages of 125 mg/day, 250 mg/day, and 375 mg/day.[33][49][52] In addition, a study found that combination of 125 mg/day flutamide with finasteride was no more effective than 125 mg/day flutamide alone in the treatment of hirsutism.[53] These findings support the use of flutamide at lower doses for hirsutism without loss of effectiveness, which may help to lower the risk of hepatotoxicity.[33] However, the risk has been found to remain even at very low doses.[12]

Scalp hair loss

Flutamide has been found to be effective in the treatment of female pattern hair loss in a number of studies.[54][55][56][57] In one study of 101 pre- and postmenopausal women, flutamide alone or in combination with an oral contraceptive produced a marked decrease in hair loss scores after 1 year of treatment, with maximum effect after 2 years of treatment and benefits maintained for another 2 years.[57][58] In a small study of flutamide with an oral contraceptive, the medication caused an increase in cosmetically acceptance hair density in 6 of 7 women with diffuse scalp hair loss.[59] In a comparative study, flutamide significantly improved scalp hair growth (21% reduction in Ludwig scores) in hyperandrogenic women after 1 year of treatment, whereas cyproterone acetate and finasteride were ineffective.[57][60]

Other uses

Flutamide has been used in case reports to decrease the frequency of spontaneous orgasms, for instance in men with post-orgasmic illness syndrome.[61][62][63]

Available forms

Flutamide is available in the form of 125 mg oral capsules and 250 mg oral tablets.[64][65]

Side effects

The side effects of flutamide are sex-dependent. In men, a variety of side effects related to androgen deprivation may occur, the most common being gynecomastia and breast tenderness.[66] Others include hot flashes, decreased muscle mass, decreased bone mass and an associated increased risk of fractures, depression,[22] and sexual dysfunction including reduced libido and erectile dysfunction.[7] In women, flutamide is, generally, relatively well tolerated, and does not interfere with ovulation.[43] The only common side effect of flutamide in women is dry skin (75%), which can be attributed to a reduction of androgen-mediated sebum production.[43][2] General side effects that may occur in either sex include dizziness, lack of appetite, gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, a greenish-bluish discoloration of the urine,[2] and hepatic changes.[22][7][67] Because flutamide is a pure antiandrogen, unlike steroidal antiandrogens like cyproterone acetate and megestrol acetate (which additionally possess progestogenic activity), it does not appear to have a risk of cardiovascular side effects (e.g., thromboembolism) or fluid retention.[68][22][6]

Gynecomastia

Flutamide, as a monotherapy, causes gynecomastia in 30 to 79% of men, and also produces breast tenderness.[69][66] However, more than 90% of cases of gynecomastia with NSAAs including flutamide are mild to moderate.[70][71][68] Tamoxifen, a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) with predominantly antiestrogenic actions, can counteract flutamide-induced gynecomastia and breast pain in men.[citation needed]

Diarrhea

Diarrhea is more common and sometimes more severe with flutamide than with other NSAAs.[40] In a comparative trial of combined androgen blockade for prostate cancer, the rate of diarrhea was 26% for flutamide and 12% for bicalutamide.[40] Moreover, 6% of flutamide-treated patients discontinued the medication due to diarrhea, whereas only 0.5% of bicalutamide-treated patients did so.[40] In the case of antiandrogen monotherapy for prostate cancer, the rates of diarrhea are 5 to 20% for flutamide, 2 to 5% for bicalutamide, and 2 to 4% for nilutamide.[40] In contrast to diarrhea, the rates of nausea and vomiting are similar among the three medications.[40]

Rare reactions

Liver toxicity

Although rare, flutamide has been associated with severe hepatotoxicity and death.[72][14][73] By 1996, 46 cases of severe cholestatic hepatitis had been reported, with 20 fatalities.[72] There have been continued case reports since, including liver transplants and death.[74][75] A 2021 review of the literature found 15 cases of serious hepatotoxicity in women treated with flutamide, including 7 liver transplantations and 2 deaths.[76]

Based on the number of prescriptions written and the number of cases reported in the MedWatch database, the rate of serious hepatotoxicity associated with flutamide treatment was estimated in 1996 as approximately 0.03% (3 per 10,000).[72][77] However, other research has suggested that the true incidence of significant hepatotoxicity with flutamide may be much greater, as high as 0.18 to 10%.[78][79] [12][74][80][81] Flutamide is also associated with liver enzyme elevations in up to 42 to 62% of patients, although marked elevations in liver enzymes (above 5 times upper normal limit) occur only in 3 to 5%.[82][83] The risk of hepatotoxicity with flutamide is much higher than with nilutamide or bicalutamide.[40][41][42] Lower doses of the medication appear to have a possibly reduced but still significant risk.[74][84] Liver function should be monitored regularly with liver function tests during flutamide treatment.[85] In addition, due to the high risk of serious hepatotoxicity, flutamide should not be used in the absence of a serious indication.[80]

The mechanism of action of flutamide-induced hepatotoxicity is thought to be due to mitochondrial toxicity.[86][87][88] Specifically, flutamide and particularly its major metabolite hydroxyflutamide inhibit enzymes in the mitochondrial electron transport chain in hepatocytes, including respiratory complexes I (NADH ubiquinone oxidoreductase), II (succinate dehydrogenase), and V (ATP synthase), and thereby reduce cellular respiration via ATP depletion and hence decrease cell survival.[86][87][88] Inhibition of taurocholate (a bile acid) efflux has also been implicated in flutamide-induced hepatotoxicity.[86][89] In contrast to flutamide and hydroxyflutamide, which severely compromise hepatocyte cellular respiration in vitro, bicalutamide does not significantly do so at the same concentrations and is regarded as non-mitotoxic.[86][88] It is thought that the nitroaromatic group of flutamide and hydroxyflutamide enhance their mitochondrial toxicity; bicalutamide, in contrast, possesses a cyano group in place of the nitro moiety, greatly reducing the potential for such toxicity.[87][90]

The hepatotoxicity of flutamide appears to depend on hydrolysis of flutamide catalyzed by an arylacetamide deacetalyse enzyme.[12] This is analogous to the hepatotoxicity that occurs with the withdrawn paracetamol (acetominophen)-related medication phenacetin.[12] In accordance, the combination of paracetamol (acetaminophen) and flutamide appears to result in additive to synergistic hepatotoxicity, indicating a potential drug interaction.[12][89]

Hepatotoxicity with flutamide may be cross-reactive with that of cyproterone acetate.[91]

Others

Flutamide has also been associated with interstitial pneumonitis (which can progress to pulmonary fibrosis).[14] The incidence of interstitial pneumonitis with flutamide was found to be 0.04% (4 per 10,000) in a large clinical cohort of 41,700 prostate cancer patients.[13] A variety of case reports have associated flutamide with photosensitivity.[14] Flutamide has been associated with several case reports of methemoglobinemia.[92][15] Bicalutamide does not appear to share this risk with flutamide.[15] Flutamide has also been associated with reports of sulfhemoglobinemia and neutropenia.[15]

Birth defects

Out of the available endocrine-disrupting compounds looked at, flutamide has a notable effect on anogenital distance in rats.[93][94])

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Antiandrogenic activity

| Antiandrogen | Relative potency |

|---|---|

| Bicalutamide | 4.3 |

| Hydroxyflutamide | 3.5 |

| Flutamide | 3.3 |

| Cyproterone acetate | 1.0 |

| Zanoterone | 0.4 |

| Description: Relative potencies of orally administered antiandrogens in antagonizing 0.8 to 1.0 mg/kg s.c. testosterone propionate-induced ventral prostate weight increase in castrated immature male rats. Sources: See template. | |

Flutamide acts as a selective, competitive, silent antagonist of the androgen receptor (AR).[5] Its active form, hydroxyflutamide, has between 10- and 25-fold higher affinity for the AR than does flutamide, and hence is a much more potent AR antagonist in comparison.[5][68][99][100] However, at high concentrations, unlike flutamide, hydroxyflutamide is able to weakly activate the AR.[5][101] Flutamide has far lower affinity for the AR than do steroidal antiandrogens like spironolactone and cyproterone acetate, and it is a relatively weak antiandrogen in terms of potency by weight, but the large dosages at which flutamide is used appear to compensate for this.[102] In accordance with its selectivity for the AR, flutamide does not interact with the progesterone, estrogen, glucocorticoid, or mineralocorticoid receptor,[103] and possesses no intrinsic progestogenic, estrogenic, glucocorticoid, or antigonadotropic activity.[2][104] However, it can have some indirect estrogenic effects via increased levels of estradiol secondary to AR blockade, and this involved in the gynecomastia it can produce. Because flutamide does not have any estrogenic, progestogenic, or antigonadotropic activity, the medication does not cause menstrual irregularities in women.[44][104] This is in contrast to steroidal antiandrogens like spironolactone and cyproterone acetate.[44] Similarly to nilutamide, bicalutamide, and enzalutamide, flutamide crosses the blood–brain barrier and exerts central antiandrogen actions.[105]

Flutamide has been found to be equal to slightly more potent than cyproterone acetate and substantially more potent than spironolactone as an antiandrogen in bioassays.[106][95] This is in spite of the fact that hydroxyflutamide has on the order of 10-fold lower affinity for the AR relative to cyproterone acetate.[106][107] Hydroxyflutamide shows about 2- to 4-fold lower affinity for the rat and human AR than does bicalutamide.[108] In addition, whereas bicalutamide has an elimination half-life of around 6 days, hydroxyflutamide has an elimination half-life of only 8 to 10 hours, a roughly 17-fold difference.[108] In accordance, at dosages of 50 mg/day bicalutamide and 750 mg/day flutamide (a 15-fold difference), circulating levels of flutamide at steady-state have been found to be approximately 7.5-fold lower than those of bicalutamide.[108] Moreover, whereas flutamide at this dosage has been found to produce a 75% reduction in prostate-specific antigen levels in men with prostate cancer, a fall of 90% has been demonstrated with this dosage of bicalutamide.[108] In accordance, 50 mg/day bicalutamide has been found to possess equivalent or superior effectiveness to 750 mg/day flutamide in a large clinical trial for prostate cancer.[108] Also, bicalutamide has been shown to be 5-fold more potent than flutamide in rats and 50-fold more potent than flutamide in dogs.[108] Taken together, flutamide appears to be a considerably less potent and efficacious antiandrogen than is bicalutamide.[108]

Dose-ranging studies of flutamide in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer alone and in combination with a GnRH agonist have been performed.[109][110]

Flutamide increases testosterone levels by 5- to 10-fold in gonadally intact male rats.[111]

CYP17A1 inhibition

Flutamide and hydroxyflutamide have been found in vitro to inhibit CYP17A1 (17α-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase), an enzyme which is required for the biosynthesis of androgens.[112] In accordance, flutamide has been found to slightly but significantly lower androgen levels in GnRH analogue-treated male prostate cancer patients[113] and women with polycystic ovary syndrome.[2] In a directly comparative study of flutamide monotherapy (375 mg once daily) versus bicalutamide monotherapy (80 mg once daily) in Japanese men with prostate cancer, after 24 weeks of treatment flutamide decreased dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) levels by about 44% while bicalutamide increased them by about 4%.[21] As such, flutamide is a weak inhibitor of androgen biosynthesis.[102] However, the clinical significance of this action may be limited when flutamide is given without a GnRH analogue to non-castrated men, as the medication markedly elevates testosterone levels into the high normal male range via prevention of AR activation-mediated negative feedback on the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis in this context.[36]

Other activities

Flutamide has been identified as an agonist of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor.[114][115] This may be involved in the hepatotoxicity of flutamide.[114]

Pharmacokinetics

The absorption of flutamide is complete upon oral ingestion.[1] Food has no effect on the bioavailability of flutamide.[1] Steady-state levels of hydroxyflutamide, the active form of flutamide, are achieved after 2 to 4 days administration.[2] Levels of hydroxyflutamide are approximately 50-fold higher than those of flutamide at steady-state.[116]

The plasma protein binding of flutamide and hydroxyflutamide are high; 94 to 96% and 92 to 94%, respectively.[1] Flutamide and its metabolite hydroxyflutamide are known to be transported by the multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (MRP1; ABCC1).[117][118]

Flutamide is metabolized by CYP1A2 (via α-hydroxylation) in the liver during first-pass metabolism[7] to its main metabolite hydroxyflutamide (which accounts for 23% of an oral dose of flutamide one hour post-ingestion),[2] and to at least five other, minor metabolites.[3] Flutamide has at least 10 inactive metabolites total, including 4-nitro-3-fluoro-methylaniline.[119]

Flutamide is excreted in various forms in the urine, the primary form being 2-amino-5-nitro-4-(trifluoromethyl)phenol.[120]

Flutamide and hydroxyflutamide have elimination half-lives of 4.7 hours and 6 hours in adults, respectively.[119][4][3] However, the half-life of hydroxyflutamide is extended to 8 hours after a single dose and to 9.6 hours at steady state) in elderly individuals.[119][6][5][3][1] The elimination half-lives of flutamide and hydroxyflutamide are regarded as too short to allow for once-daily dosing, and for this reason, flutamide is instead administered three times daily at 8-hour intervals.[121] In contrast, the newer NSAAs nilutamide, bicalutamide, and enzalutamide all have much longer half-lives,[6] and this allows for once-daily administration in their cases.[122]

Chemistry

Unlike the hormones with which it competes, flutamide is not a steroid; rather, it is a substituted anilide. Hence, it is described as nonsteroidal in order to distinguish it from older steroidal antiandrogens such as cyproterone acetate and megestrol acetate.

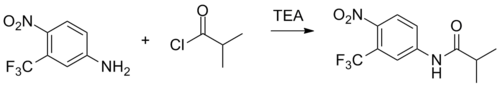

Synthesis

Schotten–Baumann reaction between 4-nitro-3-(trifluoromethyl)aniline [393-11-3] (1) with isobutanoyl chloride [79-30-1] (2) in the presence of triethylamine.

History

Flutamide was first synthesized in 1967 by Neri and colleagues at Schering Plough Corporation.[9][130][6][124] It was originally synthesized as a bacteriostatic agent, but was subsequently, and serendipitously found to possess antiandrogen activity.[2][124] The code name of flutamide during development was SCH-13521.[131] Clinical research of the medication began in 1971,[132] and it was first marketed in 1983, specifically in Chile under the brand name Drogenil and in West Germany under the brand name Flugerel.[133][134] Flutamide was not introduced in the United States until 1989; it was specifically approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer in combination with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogue.[135] The medication was first studied for the treatment of hirsutism in women in 1989.[136][137][138] It was the first "pure antiandrogen" to be studied in the treatment of hirsutism.[136] Flutamide was the first NSAA to be introduced, and was followed by nilutamide in 1989 and then bicalutamide in 1995.[139]

Society and culture

Generic names

Flutamide is the generic name of the drug and its INN, USAN, BAN, DCF, and JAN.[140][8][9] Its names in Latin, German, and Spanish are flutamidum, flutamid, and flutamida, respectively.[140][8] The medication has also been referred to by the name niftolide.[9]

Brand names

Brand names of flutamide include or have included Cebatrol, Cytomid, Drogenil, Etaconil, Eulexin, Flucinom, Flumid, Flutacan, Flutamid, Flutamida, Flutamin, Flutan, Flutaplex, Flutasin, Fugerel, Profamid, and Sebatrol, among others.[140][8][9]

Availability

Flutamide is marketed widely throughout the world, including in the United States , Canada , Europe, Australia , New Zealand, South Africa , Central and South America, East and Southeast Asia, India , and the Middle East.[140][8]

Research

Prostate cancer

The combination of an estrogen and flutamide as a form of combined androgen blockade for the treatment of prostate cancer has been researched.[141][142][143][144][145]

Enlarged prostate

Flutamide has been studied in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH; enlarged prostate) in men in several clinical studies.[146][147] It has been found to reduce prostate volume by about 25%, which is comparable to the reduction achieved with the 5α-reductase inhibitor finasteride.[148] Unfortunately, it has been associated with side effects in these studies including gynecomastia and breast tenderness (in about 50% of patients), gastrointestinal disturbances such as nausea, diarrhea, and flatulence, and hepatotoxicity, although sexual function including libido and erectile potency were maintained.[148]

Breast cancer

Flutamide was studied for the treatment of advanced breast cancer in two phase II clinical trials but was found to be ineffective.[149][150][151][152] Out of a total of 47 patients, only three short-term responses occurred.[149] However, the patients in the studies were selected irrespective of AR, ER, PR, or HER2 status, which were all unknown.[150][153]

Psychiatric disorders

Flutamide has been studied in the treatment of bulimia nervosa in women.[154][155][156][157]

Flutamide was found to be effective in the treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) in men with comorbid Tourette's syndrome in one small randomized controlled trial.[158] Conversely, it was ineffective in patients with OCD in another study.[158] More research is necessary to determine whether flutamide is effective in the treatment of OCD.[158]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 "Flutamide Capsules USP". https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/fda/fdaDrugXsl.cfm?setid=d037fb0c-881f-43d2-8693-aa1342d0130a&type=display.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 "Current aspects of antiandrogen therapy in women". Current Pharmaceutical Design 5 (9): 707–723. September 1999. doi:10.2174/1381612805666230111201150. PMID 10495361.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Cancer Chemotherapy and Biotherapy: Principles and Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 8 November 2010. pp. 679–. ISBN 978-1-60547-431-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=WL4arNFsQa8C&pg=PA679.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Prostate Cancer. Demos Medical Publishing. 2011. pp. 81–. ISBN 978-1-935281-91-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=WJkjgbRJe3EC&pg=PT81.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 24 January 2012. pp. 1373–. ISBN 978-1-60913-345-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=Sd6ot9ul-bUC&pg=PA1373.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 "Antiandrogen Monotherapy in the Treatment of Prostate Cancer". Textbook of Prostate Cancer: Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment: Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment. CRC Press. 1 March 1999. pp. 279–280. ISBN 978-1-85317-422-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=GreZlojD-tYC&pg=PA280.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 "Chapter 103: Anticancer Drugs II: Hormonal Agents, Targeted Drugs, and Other Noncytotoxic Anticancer Drugs". Pharmacology for Nursing Care. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2013. pp. 1297–. ISBN 978-1-4377-3582-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=_4SwO2dHcAIC&pg=PA1297.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. January 2000. pp. 466–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=5GpcTQD_L2oC&pg=PA466.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. 14 November 2014. pp. 573–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=0vXTBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA573.

- ↑ "Polycystic Ovary Syndrome - Treatment - NHS Choices". Nhs.uk. 2011-10-17. http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Polycystic-ovarian-syndrome/Pages/Treatment.aspx.

- ↑ "Prostate Cancer". Manual of Medical Treatment in Urology. JP Medical Ltd. 30 November 2013. pp. 120–. ISBN 978-93-5090-844-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=i9-LAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA120.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 "Flutamide-induced hepatotoxicity: ethical and scientific issues". European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 21 (1 Suppl): 69–77. March 2017. PMID 28379593.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Pneumonitis associated with nonsteroidal antiandrogens: presumptive evidence of a class effect". Annals of Internal Medicine 137 (7): 625. October 2002. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-137-7-200210010-00029. PMID 12353966. "An estimated 0.77% of the 6,480 nilutamide-treated patients, 0.04% of the 41,700 flutamide-treated patients, and 0.01% of the 86,800 bicalutamide-treated patients developed pneumonitis during the study period.".

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Meyler's Side Effects of Drugs in Cancer and Immunology. Elsevier. 19 April 2010. pp. 318–319. ISBN 978-0-08-093288-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=OSj_yr7nU6MC&pg=PT318.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 "Tolerability of Nonsteroidal Antiandrogens in the Treatment of Advanced Prostate Cancer". The Oncologist 2 (1): 18–27. 1997. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2-1-18. PMID 10388026.

- ↑ (in en) Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. 2006. p. 515. ISBN 9783527607495. https://books.google.com/books?id=FjKfqkaKkAAC&pg=PA515.

- ↑ "Adjuvant Hormonal Treatment - The Bicalutamide Early Prostate Cancer Program". Controversies in the Treatment of Prostate Cancer. Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers. 1 January 2008. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-3-8055-8524-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=4J4OCRyHWRYC&pg=PA41. "Latest studies suggest that [flutamide] also reduces adrenal and ovarian androgen synthesis [58,59]. [...] No alteration in the hormone levels has been observed in patients treated with flutamide for 6 or 12 months [61,62]. However in other studies flutamide decreased circulating concentrations of DHEAS as well as androstenedione, total testosterone and 3a-androstanediol glucuronide, in young women with PCOS [41,59]. These effects may be due to inhibition of adrenal 17-20 lyase [17,63]. Although there was no effect on gonadotropin response to GnRH, basal levels of FSH showed a rise associated with a small fall of LH [64]."

- ↑ World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2021. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ↑ Scher, Howard I. (2005). "Hyperplastic and Malignant Diseases of the Prostate". In Dennis L. Kasper, Anthony S. Fauci, Dan L. Longo, Eugene Braunwald, Stephen L. Hauser, & J. Larry Jameson (Eds.), Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (16th edition), pp. 548–9. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ "Androgen receptor antagonists for prostate cancer therapy". Endocrine-Related Cancer 21 (4): T105–T118. August 2014. doi:10.1530/ERC-13-0545. PMID 24639562.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 "A Randomized Control Trial Comparing the Efficacy of Antiandrogen Monotherapy: Flutamide vs. Bicalutamide". Hormones & Cancer 6 (4): 161–167. August 2015. doi:10.1007/s12672-015-0226-1. PMID 26024831.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 "Sipuleucel-T - A Model for Immunotherapy Trial Development". Prostate Cancer: Science and Clinical Practice. Elsevier Science. 29 September 2015. pp. 516–521, 534–540. ISBN 978-0-12-800592-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=292cBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA530.

- ↑ "Bicalutamide (Casodex) in the treatment of prostate cancer". Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy 4 (1): 37–48. February 2004. doi:10.1586/14737140.4.1.37. PMID 14748655.

- ↑ "Flare Associated with LHRH-Agonist Therapy". Reviews in Urology 3 (Suppl 3): S10–S14. 2001. PMID 16986003.

- ↑ "Disease flare with gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues. How serious is it?". Drug Safety 8 (4): 265–270. April 1993. doi:10.2165/00002018-199308040-00001. PMID 8481213.

- ↑ "Inhibition of PSA flare in prostate cancer patients by administration of flutamide for 2 weeks before initiation of treatment with slow-releasing LH-RH agonist". International Journal of Clinical Oncology 6 (1): 29–33. February 2001. doi:10.1007/PL00012076. PMID 11706524.

- ↑ "Influence of different types of antiandrogens on luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone analogue-induced testosterone surge in patients with metastatic carcinoma of the prostate". The Journal of Urology 144 (4): 934–941. October 1990. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(17)39625-8. PMID 2144596.

- ↑ "Optimal starting time for flutamide to prevent disease flare in prostate cancer patients treated with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist". Urologia Internationalis 66 (3): 135–139. 2001. doi:10.1159/000056592. PMID 11316974.

- ↑ "Flutamide eliminates the risk of disease flare in prostatic cancer patients treated with a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist". The Journal of Urology 138 (4): 804–806. October 1987. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(17)43380-5. PMID 3309363.

- ↑ "A controlled trial of leuprolide with and without flutamide in prostatic carcinoma". The New England Journal of Medicine 321 (7): 419–424. August 1989. doi:10.1056/NEJM198908173210702. PMID 2503724.

- ↑ "Combination treatment in M1 prostate cancer". Cancer 72 (12 Suppl): 3880–3885. December 1993. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19931215)72:12+<3880::AID-CNCR2820721724>3.0.CO;2-4. PMID 8252509.

- ↑ "Palliativtherapie des hämatogen metastasierten Prostatakarzinoms". Prostatakarzinom — urologische und strahlentherapeutische Aspekte: urologische und strahlentherapeutische Aspekte. Springer-Verlag. 7 March 2013. pp. 99–. ISBN 978-3-642-60064-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=wdTLBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA99.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 "Hirsutism: an evidence-based treatment update". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology 15 (3): 247–266. July 2014. doi:10.1007/s40257-014-0078-4. PMID 24889738.

- ↑ "Hyperandrogenism". Gynecology: Integrating Conventional, Complementary, and Natural Alternative Therapy. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2002. pp. 86–. ISBN 978-0-7817-2761-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=TYlZsGdwqrQC&pg=PA86.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "Female Pattern Hair Loss". Hair Growth and Disorders. Springer Science & Business Media. 26 June 2008. pp. 181–. ISBN 978-3-540-46911-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=pHrX2-huQCoC&pg=PA181.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 "Clinical Use and Abuse of Androgens and Antiandrogens". Principles and Practice of Endocrinology and Metabolism. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2001. pp. 1196, 1208. ISBN 978-0-7817-1750-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=FVfzRvaucq8C&pg=PA1196.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Müderri̇s, İ. İ., & Öner, G. (2009). Flutamide and Bicalutamide Treatment in Hirsutism. Turkiye Klinikleri Journal of Endocrinology-Special Topics, 2(2), 110. http://www.turkiyeklinikleri.com/article/en-hirsutizm-tedavisinde-flutamid-ve-bikalutamid-kullanimi-55753.html

- ↑ "Update on idiopathic hirsutism: diagnosis and treatment". Acta Clinica Belgica 68 (4): 268–274. 2013. doi:10.2143/ACB.3267. PMID 24455796.

- ↑ "New alternative treatment in hirsutism: bicalutamide 25 mg/day". Gynecological Endocrinology 16 (1): 63–66. February 2002. doi:10.1080/gye.16.1.63.66. PMID 11915584.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 40.4 40.5 40.6 "Nonsteroidal Antiandrogens". Hormone Therapy in Breast and Prostate Cancer. Humana Press. 2009. pp. 347–368. doi:10.1007/978-1-59259-152-7_16. ISBN 978-1-60761-471-5.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Biological Reactive Intermediates Vi: Chemical and Biological Mechanisms in Susceptibility to and Prevention of Environmental Diseases. Springer Science & Business Media. 6 December 2012. pp. 37–. ISBN 978-1-4615-0667-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=xRflBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA37.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Prostate Cancer. Springer Science & Business Media. 5 June 2007. pp. 256–. ISBN 978-3-540-40901-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=Bg6ZbqhhboUC&pg=PA256.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 43.4 "Ovarian Suppression and Treatment of Hirsutism". Androgen Excess Disorders in Women. Springer Science & Business Media. 8 November 2007. pp. 384–. ISBN 978-1-59745-179-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ch-BsGAOtucC&pg=PA384.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 "Management of acne vulgaris with hormonal therapies in adult female patients". Dermatologic Therapy 28 (3): 166–172. 2015. doi:10.1111/dth.12231. PMID 25845307.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 "Is hormonal treatment still an option in acne today?". The British Journal of Dermatology 172 (Suppl 1): 37–46. July 2015. doi:10.1111/bjd.13681. PMID 25627824.

- ↑ "Retrospective, observational study on the effects and tolerability of flutamide in a large population of patients with acne and seborrhea over a 15-year period". Gynecological Endocrinology 27 (10): 823–829. October 2011. doi:10.3109/09513590.2010.526664. PMID 21117864.

- ↑ "A Review of hormone-based therapies to treat adult acne vulgaris in women". International Journal of Women's Dermatology 3 (1): 44–52. March 2017. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.02.018. PMID 28492054.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Advanced Dermatologic Therapy II. W. B. Saunders. 2001. ISBN 978-0-7216-8258-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=vuJsAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 "Treatment of hyperandrogenism in polycystic ovary syndrome". Current Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Cambridge University Press. October 2010. pp. 132–. ISBN 978-1-906985-41-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=0rtUBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA132.

- ↑ "Endocrine disorders and hormonal therapy for adolescent acne". Current Opinion in Pediatrics 29 (4): 455–465. August 2017. doi:10.1097/MOP.0000000000000515. PMID 28562419.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 "Evidence-based approach to cutaneous hyperandrogenism in women". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 73 (4): 672–690. October 2015. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.05.026. PMID 26138647.

- ↑ "Long-term efficacy and tolerability of flutamide combined with oral contraception in moderate to severe hirsutism: a 12-month, double-blind, parallel clinical trial". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 92 (9): 3446–3452. September 2007. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-2798. PMID 17566093.

- ↑ "Hirsutism, Acne, and Hair Loss: Management of Hyperandrogenic Cutaneous Manifestations of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome". Gynecology Obstetrics & Reproductive Medicine 23 (2): 110–119. 2016. doi:10.21613/GORM.2016.613. ISSN 1300-4751.

- ↑ "Androgenetic Alopecia: An Update of Treatment Options". Drugs 76 (14): 1349–1364. September 2016. doi:10.1007/s40265-016-0629-5. PMID 27554257.

- ↑ "Hormonal therapy in female pattern hair loss". International Journal of Women's Dermatology 3 (1): 53–57. March 2017. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.01.001. PMID 28492055.

- ↑ "Evidence-based treatments for female pattern hair loss: a summary of a Cochrane systematic review". The British Journal of Dermatology 167 (5): 995–1010. November 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11166.x. PMID 23039053.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 "Female pattern alopecia: current perspectives". International Journal of Women's Health 5: 541–556. August 2013. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S49337. PMID 24039457.

- ↑ "Prospective cohort study on the effects and tolerability of flutamide in patients with female pattern hair loss". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy 45 (4): 469–475. April 2011. doi:10.1345/aph.1P600. PMID 21487083.

- ↑ "Current aspects of antiandrogen therapy in women". Current Pharmaceutical Design 5 (9): 707–723. September 1999. doi:10.2174/1381612805666230111201150. PMID 10495361. "Several trials demonstrated complete clearing of acne with flutamide [62,77]. Flutamide used in combination with an [oral contraceptive], at a dose of 500mg/d, flutamide caused a dramatic decrease (80%) in total acne, seborrhea and hair loss score after only 3 months of therapy [53]. When used as a monotherapy in lean and obese PCOS, it significantly improves the signs of hyperandrogenism, hirsutism and particularly acne [48]. [...] flutamide 500mg/d combined with an [oral contraceptive] caused an increase in cosmetically acceptable hair density, in sex of seven women suffering from diffuse androgenetic alopecia [53].".

- ↑ "Treatment of hyperandrogenic alopecia in women". Fertility and Sterility 79 (1): 91–95. January 2003. doi:10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04551-x. PMID 12524069.

- ↑ "Postorgasmic illness syndrome: two cases". Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy 28 (3): 251–255. 2002. doi:10.1080/009262302760328280. PMID 11995603.

- ↑ ""Did You Climax or Are You Just Laughing at Me?" Rare Phenomena Associated With Orgasm". Sexual Medicine Reviews 5 (3): 275–281. July 2017. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.03.004. PMID 28454896.

- ↑ "Post-orgasmic illness syndrome: history and current perspectives". Fertility and Sterility 113 (1): 13–15. January 2020. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.11.021. PMID 32033716.

- ↑ "Analogs and Antagonists of Male Sex Hormones". Translational Medicine: Molecular Pharmacology and Drug Discovery. Wiley. 2 March 2018. pp. 46–. doi:10.1002/3527600906.mcb.200500066.pub2. ISBN 978-3-527-68719-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=kuhPDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA46.

- ↑ Thomson Micromedex; United States Pharmacopeia (November 2002). Consumer Drug Reference 2003. Consumer Reports Books. ISBN 978-0-89043-971-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=x4jRPi_qOvwC.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 "Severe gynecomastia due to anti androgens intake: A case report and literature review". Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism 17 (4): 730–732. July 2013. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.113770. PMID 23961495.

- ↑ "Pharmacology of Cancer Chemotherapeutic and Immunotherapeutic Agents". Handbook of Pharmacology on Aging. CRC Press. 14 August 1996. pp. 334–. ISBN 978-0-8493-8306-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=xVIJOFh5mfMC&pg=PA334.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 68.2 "Drugs Affecting Endocrine Function". The Anticancer Drugs. Oxford University Press. 1994. pp. 219–220. ISBN 978-0-19-506739-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=nPR1L4K5HuEC&pg=PA220.

- ↑ "Management of gynaecomastia in patients with prostate cancer: a systematic review". The Lancet. Oncology 6 (12): 972–979. December 2005. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70464-2. PMID 16321765.

- ↑ "Antiandrogen treatments in locally advanced prostate cancer: are they all the same?". Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology 132 (S1): S17–S26. August 2006. doi:10.1007/s00432-006-0133-5. PMID 16845534. "Unlike CPA, non-steroidal antiandrogens appear to be better tolerated than castration, allowing patients to maintain sexual activity, physical ability, and bone mineral density, but these agents have a higher incidence of gynecomastia and breast pain (mild to moderate in > 90% of cases).".

- ↑ "Flutamide: an antiandrogen for advanced prostate cancer". DICP 24 (6): 616–623. June 1990. doi:10.1177/106002809002400612. PMID 2193461. "[...] They [in patients treated with flutamide] observed mild gynecomastia in 30 patients (57 percent), moderate gynecomastia in 19 (36 percent), and massive gynecomastia in 4 patients (8 percent). Complaints of nipple and areolar tenderness were noted in 50/53 patients (94 per- cent)." Airhart et al. reported that 42 percent of patients receiving flutamide 750 mg/d or 1500 mg/d developed gynecomastia within 12 weeks of starting treatment with an apparent direct correlation between the dose of flutamide administered and the severity of gynecomastia.25 In another study, two of five evaluable patients developed moderate gynecomastia with mild tenderness at four and eight weeks after starting flutamide 750 mg/d. Patients with preexisting gynecomastia as a result of previous endocrine therapy with estrogens sustained no worsening of their gynecomastia and may have improved symptomatically." Keating et al."".

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 "Cancer Chemotherapy". Drug-Induced Liver Disease. CRC Press. 16 October 2002. pp. 618–619. ISBN 978-0-203-90912-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=d8cgCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA618.

- ↑ "Hepatotoxicity induced by antiandrogens: a review of the literature". Urologia Internationalis 73 (4): 289–295. 2004. doi:10.1159/000081585. PMID 15604569.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 "Acute and fulminant hepatitis induced by flutamide: case series report and review of the literature". Annals of Hepatology 10 (1): 93–98. 2011. doi:10.1016/S1665-2681(19)31595-9. PMID 21301018.

- ↑ "Flutamide-induced hepatotoxicity: report of a case series". Revista Espanola de Enfermedades Digestivas 93 (7): 423–432. July 2001. PMID 11685939.

- ↑ "Flutamide Induced Liver Injury in Female Patients". European Journal of Medical and Health Sciences 2 (5). 2020. doi:10.24018/ejmed.2020.2.5.476. ISSN 2593-8339.

- ↑ "Flutamide hepatotoxicity". The Journal of Urology 155 (1): 209–212. January 1996. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)66596-0. PMID 7490837.

- ↑ "The effects of flutamide on cell-cell junctions in the testis, epididymis, and prostate". Reproductive Toxicology 81: 1–16. October 2018. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2018.06.014. PMID 29958919. "Despite its efficacy, some patients develop severe hepatotoxicity (cholestatic hepatitis) in the first 3–4 months of therapy (reported incidence of less than 1% to about 10%) [60,61]".

- ↑ "Adverse Effects of Hormones and Hormone Antagonists on the Liver". Drug-Induced Liver Disease. 2013. pp. 605–619. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-387817-5.00033-9. ISBN 9780123878175. "The frequency of liver injury with flutamide ranges from 0.18% to 5% of persons exposed, [...]"

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 "Antiandrogens". Meyler's Side Effects of Endocrine and Metabolic Drugs. Elsevier. 21 February 2009. pp. 153–. ISBN 978-0-08-093292-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=BWMeSwVwfTkC&pg=PA153.

- ↑ "Frequency of flutamide induced hepatotoxicity in patients with prostate carcinoma". Human & Experimental Toxicology 18 (3): 137–140. March 1999. doi:10.1177/096032719901800301. PMID 10215102. Bibcode: 1999HETox..18..137C.

- ↑ "Bicalutamide-induced hepatotoxicity: A rare adverse effect". The American Journal of Case Reports 15: 266–270. 2014. doi:10.12659/AJCR.890679. PMID 24967002.

- ↑ LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. 2012. https://livertox.nih.gov/Flutamide.htm.

- ↑ "Hepatotoxicity with low- and ultralow-dose flutamide: a surveillance study on 203 hyperandrogenic young females". Fertility and Sterility 98 (4): 1047–1052. October 2012. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.06.018. PMID 22795685.

- ↑ "Anti-Androgens". Insulin Resistance and Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: Pathogenesis, Evaluation, and Treatment. Springer Science & Business Media. 21 December 2009. pp. 75–. ISBN 978-1-59745-310-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=7ej6ZgqiFEsC&pg=PA75.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 86.2 86.3 "Identification of the Additional Mitochondrial Liabilities of 2-Hydroxyflutamide When Compared With its Parent Compound, Flutamide in HepG2 Cells". Toxicological Sciences 153 (2): 341–351. October 2016. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfw126. PMID 27413113.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 87.2 "Comparison of the cytotoxicity of the nitroaromatic drug flutamide to its cyano analogue in the hepatocyte cell line TAMH: evidence for complex I inhibition and mitochondrial dysfunction using toxicogenomic screening". Chemical Research in Toxicology 20 (9): 1277–1290. September 2007. doi:10.1021/tx7001349. PMID 17702527.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 88.2 "Circumventing the Crabtree effect: replacing media glucose with galactose increases susceptibility of HepG2 cells to mitochondrial toxicants". Toxicological Sciences 97 (2): 539–547. June 2007. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfm052. PMID 17361016.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 "Transport, metabolism, and hepatotoxicity of flutamide, drug-drug interaction with acetaminophen involving phase I and phase II metabolites". Chemical Research in Toxicology 20 (10): 1503–1512. October 2007. doi:10.1021/tx7001542. PMID 17900172.

- ↑ "Bioactivation and hepatotoxicity of nitroaromatic drugs". Current Drug Metabolism 7 (7): 715–727. October 2006. doi:10.2174/138920006778520606. PMID 17073576.

- ↑ "Paraphilic Disorders: Diagnosis and Treatment". Hormonal Therapy for Male Sexual Dysfunction. Wiley. 29 November 2011. pp. 94–110. doi:10.1002/9781119963820.ch8. ISBN 9780470657607.

- ↑ "Flutamide induced methemoglobinemia". The Journal of Urology 157 (4): 1363. April 1997. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(01)64982-6. PMID 9120948.

- ↑ "Anogenital distance as a toxicological or clinical marker for fetal androgen action and risk for reproductive disorders". Archives of Toxicology 93 (2): 253–272. February 2019. doi:10.1007/s00204-018-2350-5. PMID 30430187.

- ↑ "Manipulation of pre and postnatal androgen environments and anogenital distance in rats". Toxicology 368-369: 152–161. August 2016. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2016.08.021. PMID 27639664.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 "Comparison of the Hershberger assay and androgen receptor binding assay of twelve chemicals". Toxicology 195 (2–3): 177–186. February 2004. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2003.09.012. PMID 14751673.

- ↑ "The development of Casodex (bicalutamide): preclinical studies". European Urology 29 (Suppl 2): 83–95. 1996. doi:10.1159/000473846. PMID 8717469.

- ↑ "The preclinical development of bicalutamide: pharmacodynamics and mechanism of action". Urology 47 (1A Suppl): 13–25; discussion 29–32. January 1996. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(96)80003-3. PMID 8560673.

- ↑ "Receptor affinity and potency of non-steroidal antiandrogens: translation of preclinical findings into clinical activity". Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases 1 (6): 307–314. December 1998. doi:10.1038/sj.pcan.4500262. PMID 12496872.

- ↑ "Androgen Receptor Antagonists". Drug Management of Prostate Cancer. Springer Science & Business Media. 14 September 2010. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-1-60327-829-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=4KDrjeWA5-UC&pg=PA71.

- ↑ DICP: The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. Harvey Whitney Books Company. 1990. p. 617. https://books.google.com/books?id=N-JJAQAAIAAJ. "Additionally, 2-hydroxyflutamide has approximately a 25-fold greater affinity for androgen receptors than does flutamide."

- ↑ "Bicalutamide functions as an androgen receptor antagonist by assembly of a transcriptionally inactive receptor". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 277 (29): 26321–26326. July 2002. doi:10.1074/jbc.M203310200. PMID 12015321.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 "Polycyctic Ovary Syndrome". Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility: Integrating Modern Clinical and Laboratory Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. 23 March 2010. pp. 163–. ISBN 978-1-4419-1436-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=lcBEheiufVcC&pg=PA163.

- ↑ "Androgens and therapeutic aspects of antiandrogens in women". Journal of the Society for Gynecologic Investigation 2 (4): 577–592. 1995. doi:10.1177/107155769500200401. PMID 9420861.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 "Hyperandrogenism, Hirsutism, and the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome". Endocrinology: Adult and Pediatric. Elsevier Health Sciences. 18 May 2010. pp. 2401–. ISBN 978-1-4557-1126-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=W4dZ-URK8ZoC&pg=PA2401.

- ↑ Hormones - Antineoplastics: Advances in Research and Application: 2011 Edition: ScholarlyPaper. ScholarlyEditions. 9 January 2012. pp. 9–. ISBN 978-1-4649-4785-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=wpCvw4TF2ZMC&pg=PA9.

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedpmid2788775 - ↑ Feau, C. (2009). Novel Small Molecule Antagonists of the Interaction of the Androgen Receptor and Transcriptional Co-regulators. Saint Jude Children's Research Hospital Memphis TN. http://www.dtic.mil/docs/citations/ADA499611

- ↑ 108.0 108.1 108.2 108.3 108.4 108.5 108.6 "Relative potencies of flutamide and 'Casodex'". Endocrine-Related Cancer 4 (2): 197–202. 1997. doi:10.1677/erc.0.0040197. ISSN 1351-0088.

- ↑ "A dose-response study of the effect of flutamide on benign prostatic hyperplasia: results of a multicenter study". Urology 47 (4): 497–504. April 1996. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(99)80484-1. PMID 8638357.

- ↑ "Recommended dose of flutamide with LH-RH agonist therapy in patients with advanced prostate cancer". International Journal of Urology 3 (6): 468–471. November 1996. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2042.1996.tb00578.x. PMID 9170575.

- ↑ "Antiandrogen effects in models of androgen responsive cancer". Journal of Steroid Biochemistry 31 (4B): 711–718. October 1988. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(88)90022-2. PMID 3059063.

- ↑ "Inhibition of rat testicular 17 alpha-hydroxylase and 17,20-lyase activities by anti-androgens (flutamide, hydroxyflutamide, RU23908, cyproterone acetate) in vitro". Journal of Steroid Biochemistry 28 (1): 43–47. July 1987. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(87)90122-1. PMID 2956461.

- ↑ "Suppression of plasma androgens by the antiandrogen flutamide in prostatic cancer patients treated with Zoladex, a GnRH analogue". Clinical Endocrinology 32 (3): 329–339. March 1990. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1990.tb00874.x. PMID 2140542.

- ↑ 114.0 114.1 "The antiandrogen flutamide is a novel aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligand that disrupts bile acid homeostasis in mice through induction of Abcc4". Biochemical Pharmacology 119: 93–104. November 2016. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2016.08.021. PMID 27569425.

- ↑ "Anti-androgen flutamide suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor mediated induction of transforming growth factor-β1". Oncogene 34 (50): 6092–6104. December 2015. doi:10.1038/onc.2015.55. PMID 25867062.

- ↑ Lymphomas and Leukemias: Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. Wolters Kluwer Health. 29 September 2015. pp. 1029–. ISBN 978-1-4963-3828-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=n8ehCgAAQBAJ&pg=PT1029.

- ↑ "Substrates and inhibitors of human multidrug resistance associated proteins and the implications in drug development". Current Medicinal Chemistry 15 (20): 1981–2039. 2008. doi:10.2174/092986708785132870. PMID 18691054.

- ↑ "Effect of the multidrug resistance protein on the transport of the antiandrogen flutamide". Cancer Research 63 (10): 2492–2498. May 2003. PMID 12750271.

- ↑ 119.0 119.1 119.2 "Error". http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/drug-database-site/Drug%20Index/Flutamide_monograph_1April2014.pdf.

- ↑ Analytical Profiles of Drug Substances and Excipients. Academic Press. 19 March 2001. pp. 155–. ISBN 978-0-08-086122-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=uEcv7SFDWBEC&pg=PA155.

- ↑ LWW's Foundations in Pharmacology for Pharmacy Technicians. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 1 October 2009. pp. 300–. ISBN 978-0-7817-6624-1. https://archive.org/details/lwwsfoundationsi0000acos.

- ↑ Campbell-Walsh Urology: Expert Consult Premium Edition: Enhanced Online Features and Print, 4-Volume Set. Elsevier Health Sciences. 25 August 2011. pp. 2939–. ISBN 978-1-4160-6911-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=fu3BBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA2939.

- ↑ "Microscale Synthesis and Spectroscopic Analysis of Flutamide, an Antiandrogen Prostate Cancer Drug". Journal of Chemical Education 80 (12): 1439. 2003. doi:10.1021/ed080p1439. Bibcode: 2003JChEd..80.1439S.

- ↑ 124.0 124.1 124.2 "Synthesis and bacteriostatic activity of some nitrotrifluoromethylanilides". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 10 (1): 93–95. January 1967. doi:10.1021/jm00313a020. PMID 6031711.

- ↑ "Novel and Gram-Scale Green Synthesis of Flutamide". Synthetic Communications 36 (7): 859–864. 2006. doi:10.1080/00397910500464848.

- ↑ Neri RO, Topliss JG, "Substituierte Anilide [Substituted anilides]", DE patent 2130450, published 1972-12-21

- ↑ Gold EH, "Substituierte Imidate [Substituted imidates]", DE patent 2261293, published 1973-07-05, assigned to Sherico Ltd.

- ↑ Gold E, US patent 3847988, issued 1974, assigned to Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp

- ↑ Neri RO, Topliss JG, US patent 4144270, issued 1979, assigned to Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp

- ↑ "The Chemotherapy of Cancer". Smith and Williams' Introduction to the Principles of Drug Design and Action (Fourth ed.). CRC Press. 10 October 2005. pp. 489–. ISBN 978-0-203-30415-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=P2W6B9FQRKsC&pg=PA489.

- ↑ "Comparison of the biological effects of three types of testosterone inhibitors in mice.". Immunological Influence on Human Fertility: Proceedings of the Workshop on Fertility in Human Reproduction, University of Newcastle, Australia, July 11-13, 1977. Elsevier Science. 12 May 2014. pp. 167–. ISBN 978-1-4832-6895-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=4r7iBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA167.

- ↑ The Irish Reports: Containing Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Court of Appeal, the High Court of Justice, the Court of Bankruptcy, in Ireland, and the Irish Land Commission. Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for Ireland. 1990. p. 501. https://books.google.com/books?id=FQhMAQAAIAAJ.

- ↑ William Andrew Publishing (22 October 2013). Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition. Elsevier. pp. 1695–. ISBN 978-0-8155-1856-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=_J2ti4EkYpkC&pg=PA1695.

- ↑ The Irish Reports: Containing Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Court of Appeal, the High Court of Justice, the Court of Bankruptcy, in Ireland, and the Irish Land Commission. Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for Ireland. 1990. pp. 501–502. https://books.google.com/books?id=FQhMAQAAIAAJ.

- ↑ "Pharmacology and clinical use of sex steroid hormone receptor modulators". Sex and Gender Differences in Pharmacology. Springer Science & Business Media. 2 October 2012. pp. 575–. ISBN 978-3-642-30725-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=J3VxihGDh9wC&pg=PA575.

- ↑ 136.0 136.1 "Antiandrogens: clinical applications". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 37 (3): 349–362. November 1990. doi:10.1016/0960-0760(90)90484-3. PMID 2147859.

- ↑ "Flutamide in the treatment of hirsutism". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 36 (2): 155–157. October 1991. doi:10.1016/0020-7292(91)90772-w. PMID 1683319.

- ↑ "Flutamide and hirsutism". Journal of Endocrinological Investigation 17 (8): 673. September 1994. doi:10.1007/BF03349685. PMID 7868809.

- ↑ "Flourinated Drugs". Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry of Fluorine. John Wiley & Sons. 2 June 2008. pp. 327–. ISBN 978-0-470-28187-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=QMVSvZ-R7I0C&pg=PA327.

- ↑ 140.0 140.1 140.2 140.3 "Flutamide: Uses, Dosage, Side Effects & Warnings". https://www.drugs.com/international/flutamide.html.

- ↑ "Endocrine changes underlying clinical effects of low-dose estrogen-antiandrogen treatment of prostatic cancer". Endocrine Regulations 29 (1): 25–28. 1995. ISSN 0013-7200.

- ↑ "[The correlation of the hormonal and clinical effects in patients with prostatic cancer undergoing niftolid treatment in combination with low doses of synestrol"] (in uk). Likars'ka Sprava (1–2): 107–110. 1996. PMID 9005063. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/14203603.

- ↑ "Benefits of low dose estrogen-antiandrogen treatment of prostate cancer". Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Archiv für Pharmakologie 358 (1): R532. January 1998. ISSN 0028-1298.

- ↑ "Mechanisms of potentiating effect of low dose estrogens on flutamide-induced suppression of normal and cancerous prostate". Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Archiv für Pharmakologie 358 (1): R545. January 1998. ISSN 0028-1298.

- ↑ "Effects of combined treatment with niftolide and low doses of antitumor estrogen preparation, chlorotrianizene, on rat prostate". Eksperimentalʹnai͡a onkologii͡a [Experimental Oncology] 21 (3–4): 269–273. September 1999. ISSN 0204-3564. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288711102.

- ↑ "Endocrine therapies for symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia". Urology 43 (2 Suppl): 7–16. February 1994. doi:10.1016/0090-4295(94)90212-7. PMID 7509536.

- ↑ "Flutamide in treatment of benign prostatic hypertrophy". Urology 34 (4 Suppl): 64–8; discussion 87–96. October 1989. doi:10.1016/0090-4295(89)90236-7. PMID 2477936.

- ↑ 148.0 148.1 "Benign prostatic hyperplasia: diagnosis and treatment guideline". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy 31 (4): 481–486. April 1997. doi:10.1177/106002809703100415. PMID 9101011.

- ↑ 149.0 149.1 "New endocrine approaches to breast cancer". Baillière's Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 4 (1): 67–84. March 1990. doi:10.1016/S0950-351X(05)80316-7. PMID 1975167.

- ↑ 150.0 150.1 "AR Signaling in Breast Cancer". Cancers 9 (3): 21. February 2017. doi:10.3390/cancers9030021. PMID 28245550.

- ↑ "A phase II clinical trial of flutamide in the treatment of advanced breast cancer". Tumori 74 (1): 53–56. February 1988. doi:10.1177/030089168807400109. PMID 3354065.

- ↑ "Phase II study of flutamide in patients with metastatic breast cancer. A National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group study". Investigational New Drugs 6 (3): 207–210. September 1988. doi:10.1007/BF00175399. PMID 3192386.

- ↑ "Androgen Receptor as a Potential Target for Treatment of Breast Cancer". International Journal of Cancer Research and Molecular Mechanisms 3 (1). April 2017. doi:10.16966/2381-3318.129. PMID 28474005.

- ↑ "Sex Hormones and Appetite in Women: A Focus on Bulimia Nervosa". Handbook of Behavior, Food and Nutrition. 2011. pp. 1759–1767. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-92271-3_114. ISBN 978-0-387-92270-6.

- ↑ "Current pharmacotherapy options for bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 13 (14): 2015–2026. October 2012. doi:10.1517/14656566.2012.721781. PMID 22946772.

- ↑ "Marked symptom reduction in two women with bulimia nervosa treated with the testosterone receptor antagonist flutamide". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 94 (2): 137–139. August 1996. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09838.x. PMID 8883576.

- ↑ "Effects of the androgen antagonist flutamide and the serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram in bulimia nervosa: a placebo-controlled pilot study". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 25 (1): 85–88. February 2005. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000150222.31007.a9. PMID 15643104.

- ↑ 158.0 158.1 158.2 "Anti-Androgen Drugs in the Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Systematic Review". Current Medicinal Chemistry 27 (40): 6825–6836. December 2019. doi:10.2174/0929867326666191209142209. PMID 31814547.

Further reading

- "Flutamide and Other Antiandrogens in the Treatment of Advanced Prostatic Carcinoma". Endocrine Therapies in Breast and Prostate Cancer. Cancer Treatment and Research. 39. 1988. pp. 131–145. doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-1731-9_9. ISBN 978-1-4612-8974-6.

- "Flutamide. A preliminary review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic efficacy in advanced prostatic cancer". Drugs 38 (2): 185–203. August 1989. doi:10.2165/00003495-198938020-00003. PMID 2670515.

- "Pharmacology and pharmacokinetics of flutamide". Urology 34 (4 Suppl): 19–21; discussion 46–56. October 1989. doi:10.1016/0090-4295(89)90230-6. PMID 2477934.

- "The use of flutamide as monotherapy in the treatment of advanced prostate cancer". Progress in Clinical and Biological Research 303: 117–121. 1989. PMID 2674980.

- "Combination therapy with castration and flutamide: today's treatment of choice for prostate cancer". Journal of Steroid Biochemistry 33 (4B): 817–821. October 1989. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(89)90499-8. PMID 2689788.

- "Flutamide: an antiandrogen for advanced prostate cancer". DICP 24 (6): 616–623. June 1990. doi:10.1177/106002809002400612. PMID 2193461.

- "Flutamide. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic use in advanced prostatic cancer". Drugs & Aging 1 (2): 104–115. March 1991. doi:10.2165/00002512-199101020-00003. PMID 1794008.

- "Mechanism of action and pure antiandrogenic properties of flutamide". Cancer 72 (12 Suppl): 3816–3827. December 1993. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19931215)72:12+<3816::aid-cncr2820721711>3.0.co;2-3. PMID 8252497.

- "Nonsteroidal antiandrogens: a therapeutic option for patients with advanced prostate cancer who wish to retain sexual interest and function". BJU International 87 (1): 47–56. January 2001. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.00988.x. PMID 11121992.

- "Low-dose flutamide-metformin therapy for hyperinsulinemic hyperandrogenism in non-obese adolescents and women". Human Reproduction Update 12 (3): 243–252. 2006. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmi054. PMID 16407452.

- "Acute and fulminant hepatitis induced by flutamide: case series report and review of the literature". Annals of Hepatology 10 (1): 93–98. 2011. doi:10.1016/S1665-2681(19)31595-9. PMID 21301018.

- "Flutamide-induced hepatotoxicity: ethical and scientific issues". European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 21 (1 Suppl): 69–77. March 2017. PMID 28379593.

{{Navbox

| name = Androgens and antiandrogens | title = Androgens and antiandrogens | state = collapsed | listclass = hlist | groupstyle = text-align:center;

| group1 = Androgens

(incl. AAS)

| list1 =

| group2 = Antiandrogens | list2 = {{Navbox|child | groupstyle = text-align:center; | groupwidth = 9em;

| group1 = AR antagonists | list1 =

- Steroidal: Abiraterone acetate

- Canrenone

- Chlormadinone acetate

- Cyproterone acetate

- Delmadinone acetate

- Dienogest

- Drospirenone

- Medrogestone

- Megestrol acetate

- Nomegestrol acetate

- Osaterone acetate

- Oxendolone

- Potassium canrenoate

- Spironolactone

- Nonsteroidal: Apalutamide

- Bicalutamide

- Cimetidine

- Darolutamide

- Enzalutamide

- Flutamide

- Ketoconazole

- Nilutamide

- Seviteronel†

- Topilutamide (fluridil)

| group2 = Steroidogenesis| list2 =

inhibitors

| 5α-Reductase | |

|---|---|

| Others |

| group3 = Antigonadotropins | list3 =

- D2 receptor antagonists (prolactin releasers) (e.g., domperidone, metoclopramide, risperidone, haloperidol, chlorpromazine, sulpiride)

- Estrogens (e.g., bifluranol, [[diethylstilbestrol, estradiol, estradiol esters, ethinylestradiol, ethinylestradiol sulfonate, paroxypropione)

- GnRH agonists (e.g., leuprorelin)

- GnRH antagonists (e.g., cetrorelix)

- Progestogens (incl., chlormadinone acetate, [[cyproterone acetate, hydroxyprogesterone caproate, gestonorone caproate, [[Chemistry:Medroxyprogesterone medroxyprogesterone acetate, Chemistry:Megestrol acetate|megestrol acetate]])

| group4 = Others | list4 =

- Androstenedione immunogens: Androvax (androstenedione albumin)

- Ovandrotone albumin (Fecundin)

}}

| liststyle = background:#DDDDFF;| list3 =

- #WHO-EM

- ‡Withdrawn from market

- Clinical trials:

- †Phase III

- §Never to phase III

- See also

- Androgen receptor modulators

- Estrogens and antiestrogens

- Progestogens and antiprogestogens

- List of androgens/anabolic steroids

}}

|