Chemistry:Metoclopramide

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌmɛtəˈklɒprəmaɪd/ |

| Trade names | Primperan, Reglan, others[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a684035 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous, intramuscular, nasal spray |

| Drug class | D2 receptor antagonist; 5-HT3 receptor antagonist; 5-HT4 receptor agonist; Prolactin releaser |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 80 ± 15% (by mouth) |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 5–6 hours |

| Excretion | Urine: 70–85% Feces: 2% |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

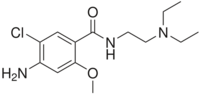

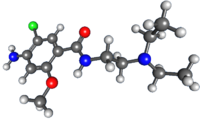

| Formula | C14H22ClN3O2 |

| Molar mass | 299.80 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 147.3 °C (297.1 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Metoclopramide is a medication used for stomach and esophageal problems.[4] It is commonly used to treat and prevent nausea and vomiting, to help with emptying of the stomach in people with delayed stomach emptying, and to help with gastroesophageal reflux disease.[5] It is also used to treat migraine headaches.[6]

Common side effects include: feeling tired, diarrhea, and feeling restless. More serious side effects include neuroleptic malignant syndrome and depression.[5] It is thus rarely recommended that people take the medication for longer than twelve weeks.[5] No evidence of harm has been found after being taken by many pregnant women.[5][7] It belongs to the group of medications known as dopamine-receptor antagonists and works as a prokinetic.[5]

In 2012, metoclopramide was one of the top 100 most prescribed medications in the United States.[8] It is available as a generic medication.[5] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[9] In 2020, it was the 352nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 600,000 prescriptions.[10]

Medical uses

Nausea

Metoclopramide is commonly used to treat nausea and vomiting associated with conditions such as uremia, radiation sickness, cancer and the effects of chemotherapy, labor, infection, and emetogenic drugs.[5][11][12][13] As a perioperative anti-emetic, the effective dose is usually 25 to 50 mg (compared to the usual 10 mg dose).

It is also used in pregnancy as a second choice for treatment of hyperemesis gravidarum (severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy).[5]

It is also used preventatively by some EMS providers when transporting people who are conscious and spinally immobilized.[14]

Migraine

In migraine headaches, metoclopramide may be used in combination with paracetamol (acetaminophen) or in combination with aspirin.[15]

Gastroparesis

Evidence also supports its use for gastroparesis, a condition that causes the stomach to empty poorly, and as of 2010 it was the only drug approved by the FDA for that condition.[5][16]

It is also used in gastroesophageal reflux disease.[5][3]

Lactation

While metoclopramide is used to try to increase breast milk production, evidence for its effectiveness for this is poor.[17] Its safety for this use is also unclear.[18]

Procedures

Intravenous metoclopramide is used in small-bowel follow-through, small-bowel enema, and radionuclide gastric-emptying studies to reduce the time taken for barium to go through the intestines, thus reducing the total time needed for the procedures. Metoclopramide also prevents vomiting after oral ingestion of barium.[19]

Contraindications

Metoclopramide is contraindicated in pheochromocytoma. It should be used with caution in Parkinson's disease since, as a dopamine antagonist, it may worsen symptoms. Long-term use should be avoided in people with clinical depression, as it may worsen one's mental state.[12] It is contraindicated for people with a suspected bowel obstruction,[5] in epilepsy, if a stomach operation has been performed in the previous three or four days, perforation or blockage of the stomach, and in newborn babies.[13]

The safety of the drug was reviewed by the European Medicines Agency in 2011, which determined that it should not be prescribed in high doses, for periods of more than five days, or given to children below 1 year of age. They suggested its use in older children should be restricted to treating post-chemotherapy or post-surgery nausea and vomiting, and even then only for patients where other treatments have failed. For adults, they recommended its use be restricted to treating migraines and post-chemotherapy or post-surgery patients.[20][21]

Pregnancy

Metoclopramide has long been used in all stages of pregnancy with no evidence of harm to the mother or foetus.[22] A large cohort study of babies born to Israeli women exposed to metoclopramide during pregnancy found no evidence that the drug increases the risk of congenital malformations, low birth weight, preterm birth, or perinatal mortality.[23] A large cohort study in Denmark found, in addition, no association between metoclopramide exposure and miscarriage.[24] Metoclopramide is excreted into milk.[22]

Infants

A systematic review found a wide range of reported outcomes for treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in infants and concluded a "poor" rating of evidence and "inconclusive" rating of safety and efficacy for the treatment of GERD in infants.[25]

Side effects

Common adverse drug reactions (ADRs) associated with metoclopramide therapy include restlessness (akathisia), and focal dystonia. Infrequent ADRs include hypertension, hypotension, hyperprolactinaemia leading to galactorrhea, headache, and extrapyramidal effects such as oculogyric crisis.[12][3]

Metoclopramide may be the most common cause of drug-induced movement disorders.[26] The risk of extrapyramidal effects is increased in people under 20 years of age, and with high-dose or prolonged therapy.[11][12] Tardive dyskinesia may be persistent and irreversible in some people. The majority of reports of tardive dyskinesia occur in people who have used metoclopramide for more than three months.[26] Consequently, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends that metoclopramide be used for short-term treatment, preferably less than 12 weeks. In 2009, the FDA required all manufacturers of metoclopramide to issue a black box warning regarding the risk of tardive dyskinesia with chronic or high-dose use of the drug.[26]

Dystonic reactions may be treated with benzatropine, diphenhydramine, trihexyphenidyl, or procyclidine. Symptoms usually subside with diphenhydramine injected intramuscularly.[3] Agents in the benzodiazepine class of drugs may be helpful, but benefits are usually modest and side effects of sedation and weakness can be problematic.[27]

In some cases, the akathisia effects of metoclopramide are directly related to the infusion rate when the drug is administered intravenously. Side effects were usually seen in the first 15 min after the dose of metoclopramide.[28]

Rare side effects

Diabetes, age, and female gender are risk factors that increase the likelihood of experiencing a neuropsychiatric side effect of metoclopramide.[29]

- Panic disorder[30]

- Major depressive disorder[30]

- Agoraphobia[30]

- Agranulocytosis, supraventricular tachycardia, hyperaldosteronism, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, akathisia and tardive dyskinesia.

- Methaemoglobinaemia*[12][3]

Pharmacology

Metoclopramide appears to bind to dopamine D2 receptors with nanomolar affinity (Ki = 28.8 nM),[31] where it is a receptor antagonist, and is also a mixed 5-HT3 receptor antagonist/5-HT4 receptor agonist.[29]

Mechanism of action

The antiemetic action of metoclopramide is due to its antagonist activity at D2 receptors in the chemoreceptor trigger zone in the central nervous system — this action prevents nausea and vomiting triggered by most stimuli.[32] At higher doses, 5-HT3 antagonist activity may also contribute to the antiemetic effect.[33][failed verification]

The gastroprokinetic activity of metoclopramide is mediated by muscarinic activity, D2 receptor antagonist activity, and 5-HT4 receptor agonist activity.[34][35] The gastroprokinetic effect itself may also contribute to the antiemetic effect.[citation needed] Metoclopramide also increases the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter.[36]

Metoclopramide might influence mood because of its antagonistic blockade on 5-HT3 and agonistic (activating) action on 5-HT4.[29]

Chemistry

Metoclopramide is a substituted benzamide; cisapride and mosapride are structurally related.[33]

History

Metoclopramide was first described by Louis Justin-Besançon and Charles Laville in 1964, while working to improve the anti-dysrhythmic properties of procainamide.[37][38][39][40] That research project also produced the product sulpiride.[37] The first clinical trials were published by Tourneu et al. in 1964 and by Boisson and Albot in 1966.[40] Justin-Besançon and Laville worked for Laboratoires Delagrange[37] and that company introduced the drug as Primperan in 1964.[41][42] Laboratoires Delagrange was acquired by Synthelabo in 1991[43][44] which eventually became part of Sanofi.[45]

A.H. Robins introduced the drug in the US under the brand name Reglan in 1979[46] as an injectable[47] and an oral form was approved in 1980.[48] in 1989 A.H. Robins was acquired by American Home Products,[49] which changed its name to Wyeth in 2002.[50]

The drugs were initially used to control nausea for people with severe headaches or migraines, and later uses for nausea caused by radiation therapy and chemotherapy, and later yet for treating nausea caused by anesthesia.[40] In the US the injectable form was labelled for chemotherapy-induced nausea and the oral form was eventually labelled for gastroesophageal reflux disease.[51]

It became widely used in the 1980s, becoming the most commonly used drug to treat anesthesia-induced nausea[40] and for treating gastritis in emergency rooms.[52]

The first generics were introduced in 1985.[51][53]

In the early 1980s signs began to emerge in pharmacovigilance studies from Sweden that the drug was causing tardive dyskinesia in some patients.[54] The FDA required a warning about tardive dyskinesia to be added to the drug label in 1985 stating that: "tardive dyskinesia . . . may develop in patients treated with metoclopramide,” and warned against use longer than 12 weeks, as that was how long the drug has been tested.[55][56] In 2009 the FDA required that a black box warning be added to the label.[16][26]

The emergence of this severe side effect led to a wave of product liability litigation against generic manufacturers as well as Wyeth.[57] The litigation was complicated since there was a lack of clarity in jurisdiction between state laws, where product liability is determined, and federal law, which determines how drugs are labelled, as well as between generics companies, which had no control over labelling, and the originator company, which did.[57][58] The litigation yielded at least two important cases. In Conte v. Wyeth in the California state courts, the claims of the plaintiff against the generic companies Pliva, Teva, and Purepac that had sold the drugs that the plaintiff actually took, and the claims against Wyeth, whose product the plaintiff never took, were all dismissed by the trial court, but the case was appealed, and in 2008 the appellate court upheld the dismissal of the cases against the generic companies, but reversed on Wyeth, allowing the case against Wyeth to proceed.[57][58][59] This established an "innovator liability" or "pioneer liability" for pharmaceutical companies.[57] The precedent was not widely followed in California nor in other states.[58] Litigation over the same issues related to metoclopramide also reached the US Supreme Court in Pliva, Inc. v. Mensing,[60] in which the court held in 2011 that generic companies cannot be held liable for information, or the lack of information, on the originator's label.[56][58][61] As of August 2015 there were about 5000 suits pending across the US and efforts to consolidate them into a class action had failed.[citation needed]

Shortly following the Pliva decision, the FDA proposed a rule change that would allow generics manufacturers to update the label if the originating drug had been withdrawn from the market for reasons other than safety.[62] As of May 2016 the rule, which turned out to be controversial since it would open generic companies to product liability suits, was still not finalized, and the FDA had stated the final rule would be issued in April 2017.[63] The FDA issued a draft guidance for generic companies to update labels in July 2016.[64]

Society and culture

Brand names

| A | Adco-Contromet, Aeroflat (metoclopramide and dimeticone), Afipran, Anaflat Compuesto (metoclopramide and simeticone; pancreatin), Anagraine (metoclopramide and paracetamol),[66] Anausin Métoclopramide, Anolexinon, Antiementin, Antigram (Metoclopramide and Acetylsalicylic Acid), Aswell |

| B | Balon, Betaclopramide, Bio-Metaclopramide, Bitecain AA |

| C | Carnotprim, Carnotprim, Cephalgan (metoclopramide and carbasalate calcium), Cerucal, Chiaowelgen, Chitou, Clifar (Metoclopramide and Simeticone), Clodaset (metoclopramide and ondansetron), Clodoxin (metoclopramide and pyridoxine), Clomitene, Clopamon, Clopan, Cloperan, Cloprame, Clopramel, Clozil |

| D | Damaben, Degan, Delipramil, Di-Aero OM (metoclopramide and simeticone), Dibertil, Digenor (Metoclopramide and Dimeticone), Digespar (Metoclopramide and Simeticone), Digestivo S. Pellegrino, Dikinex Repe (Metoclopramide and Pancreatin), Dirpasid, Doperan, Dringen |

| E | Egityl (metoclopramide and acetylsalicylic Acid), Elieten, Eline, Elitan, Emenil, Emeprid (veterinary use), Emeran, Emetal, Emoject, Emperal, Enakur, Enteran, Enzimar, Espaven M.D. (Metoclopramide and Dimethicone), Ethiferan, Eucil |

| F | Factorine (Metoclopramide and Simeticone) |

| G | Gastro-Timelets, Gastrocalm, Gastronerton, Gastrosil, Geneprami |

| H | H-Peran, Hawkperan, Hemibe, Horompelin |

| I | Imperan, Isaprandil, Itan |

| J | |

| K | K.B. Meta, Klometol, Klopra |

| L | Lexapram, Linperan, Linwels |

| M | Malon, Manosil, Maril, Matolon, Maxeran, Maxolon, Maxolone, Meclam, Meclid, Meclizine, Meclomid, Meclopstad, Meniperan, Mepram, Met-Sil, Metajex, Metalon, Metamide, Metilprednisolona Richet, Metoceolat, Metoclor, Metoco, Metocol, Metocontin, Metomide (veterinary use), Metonia, Metopar (Metoclopramide and Paracetamol), Metopar (Metoclopramide and Paracetamol), Metopelan, Metoperan, Metoperon, Metopran, Metotag, Metozolv, Metpamid, Metsil, Mevaperan, Midatenk, Migaura (Metoclopramide and Paracetamol), Migpriv (Metoclopramide and Acetylsalicylic Acid), Migracid (Metoclopramide and Paracetamol), Migraeflux MCP (Metoclopramide and Paracetamol), Migrafin (Metoclopramide and Aspirin), Migralave + MCP (Metoclopramide and Paracetamol), MigraMax (Metoclopramide and Acetylsalicylic Acid), Migräne-Neuridal (Metoclopramide and Paracetamol), Migränerton (Metoclopramide and Paracetamol), Motilon |

| N | N-Metoclopramid, Nastifran, Nausil, Nevomitan, Nilatika, Novomit |

| O | Opram |

| P | Pacimol-M (Metoclopramide and Paracetamol), Pangastren (Metoclopramide and Simeticone), Paramax (Metoclopramide and Paracetamol), Paspertin, Peraprin, Perinorm, Perinorm-MPS (Metoclopramide and Dimeticone), Perone, Piralen, Plamide, Plamine, Plasil, PMS-Metoclopramide, Podokedon, Polun, Poriran, Pradis, Pramidin, Pramidyl, Pramin, Praux, Premig (Metoclopramide and Acetylsalicylic Acid), Premosan, Prenderon, Prevomic, Primadol (Metoclopramide and Paracetamol), Primavera-N, Premier, Primlan, Primperan, Primperil, Primperoxane (Metoclopramide and Dimeticone), Primram, Primran, Primsel, Pripram, Prokinyl, Promeran, Prometin, Prowel, Pulin, Pulinpelin, Pulperan, Pusuan, Putelome, Pylomid |

| Q | |

| R | R-J, Raclonid, Randum, Reglan, Reglomar, Reliveran, Remetin, Riamide, Rilaquin, Rowelcon |

| S | Sabax Metoclopramide, Sinprim, Sinthato, Soho, Indonesia, Sotatic, Stomallin, Suweilan |

| T | Talex (Metoclopramide and Pancreatin), Tivomit, Tomit, Torowilon |

| U | |

| V | Vertivom, Vilapon, Vitamet, Vomend (veterinary use), Vomesea, Vomiles, Vomipram, Vomitrol, Vosea |

| W | Wei Lian, Winperan |

| X | |

| Y | |

| Z | Zudaw |

Veterinary use

Metoclopramide is commonly used to prevent vomiting in cats and dogs. It is also used as a gut stimulant in rabbits.[67]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "International names for metoclopramide". Drugs.com. https://www.drugs.com/international/metoclopramide.html.

- ↑ "Metoclopramide Use During Pregnancy". 27 February 2020. https://www.drugs.com/pregnancy/metoclopramide.html.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "Reglan- metoclopramide hydrochloride tablet". 19 June 2020. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=de55c133-eb08-4a35-91a2-5dc093027397.

- ↑ "Metoclopramide". https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a684035.html.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 "Metoclopramide hydrochloride". Monograph. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. https://www.drugs.com/monograph/metoclopramide-hydrochloride.html.

- ↑ "Acute Migraine Treatment in Adults". Headache 55 (6): 778–793. June 2015. doi:10.1111/head.12550. PMID 25877672.

- ↑ "Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database". Australian Government. 3 March 2014. http://www.tga.gov.au/hp/medicines-pregnancy.htm#.U1Yw8Bc3tqw.

- ↑ "Top 200 Drugs of 2012". Pharmacy Times. http://www.pharmacytimes.com/publications/issue/2013/July2013/Top-200-Drugs-of-2012.

- ↑ World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2021. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ↑ "Metoclopramide - Drug Usage Statistics". https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Metoclopramide.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Maxolon (Australian Approved Product Information)". Valeant Pharmaceuticals. 2000. http://www.mydr.com.au/medicines/cmis/maxolon-tablets.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Rossi S., ed (2006). Australian Medicines Handbook. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook. ISBN 978-0-9757919-2-9.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Metoclopramide Hydrochloride 5mg/5ml Oral Solution - - (eMC)". http://xpil.medicines.org.uk/ViewPil.aspx?DocID=8068.

- ↑ "Ambulance Victoria Clinical Guideline A0701""Oxygen Therapy". Ambulance Victoria. 2013. http://www.ambulance.vic.gov.au/media/docs/Adult%20CPG%20wm-a01f0e1e-4fc0-405c-bc83-3136adf4a723-0.pdf.

- ↑ "Paracetamol (acetaminophen) with or without an antiemetic for acute migraine headaches in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013 (4): CD008040. April 2013. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008040.pub3. PMID 23633349.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Review article: metoclopramide and tardive dyskinesia". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 31 (1): 11–19. January 2010. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04189.x. PMID 19886950.

- ↑ "A Review of Herbal and Pharmaceutical Galactagogues for Breast-Feeding". The Ochsner Journal 16 (4): 511–524. 2016. PMID 27999511.

- ↑ "The use of galactogogues in the breastfeeding mother". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy 46 (10): 1392–1404. October 2012. doi:10.1345/aph.1R167. PMID 23012383.

- ↑ Chapman and Nakielny's Guide to Radiological Procedures. Elsevier. 2018. pp. 48, 55, 87. ISBN 9780702071669.

- ↑ "Metoclopramide-containing medicines". European Medicines Agency. 17 September 2018. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/referrals/Metoclopramide-containing_medicines/human_referral_000349.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac05805c516f.

- ↑ "Metoclopramide only containing medicinal products". EMA/753989/2013 Assessment report. European Medicines Agency. 20 December 2013. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Referrals_document/Metoclopramide_31/WC500160356.pdf.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2008. pp. 1197–1200. ISBN 978-0-7817-7876-3. https://archive.org/details/drugsinpregnancy0008brig. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- ↑ "The safety of metoclopramide use in the first trimester of pregnancy". The New England Journal of Medicine 360 (24): 2528–2535. June 2009. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0807154. PMID 19516033.

- ↑ "Metoclopramide in pregnancy and risk of major congenital malformations and fetal death". JAMA 310 (15): 1601–1611. October 2013. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.278343. PMID 24129464.

- ↑ "Metoclopramide for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease in infants: a systematic review". Pediatrics 118 (2): 746–752. August 2006. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-2664. PMID 16882832.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 "FDA requires boxed warning and risk mitigation strategy for metoclopramide-containing drugs" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 26 February 2009. Retrieved 11 June 2009. "Lay Summary – WebMD". http://www.webmd.com/digestive-disorders/news/20090227/metoclopramide-drugs-get-black-box-warning.

- ↑ "Chapter 372. Parkinson's Disease and Other Movement Disorders.". Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (18th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. 2012.

- ↑ Clinical Neurotoxicology E-Book: Syndromes, Substances, Environments. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2009. p. 393. ISBN 978-0-323-07099-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=vOTM-_jGQ50C&dq=infusion+rate+metoclopramide&pg=PA393.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 "Metoclopramide and homicidal ideation: a case report and literature review". Psychosomatics 52 (5): 403–409. 2011. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2011.02.001. PMID 21907057.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 "Metoclopramide". Statpearls. 2020. PMID 30137802.

- ↑ "Prediction of catalepsies induced by amiodarone, aprindine and procaine: similarity in conformation of diethylaminoethyl side chain". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 287 (2): 725–732. November 1998. PMID 9808703. http://jpet.aspetjournals.org/content/287/2/725.full.pdf. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ↑ Pharmacology (5th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. 2003. ISBN 978-0-443-07145-4.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 "Timing of Analog Research in Medicinal Chemistry. Chapter 6". Drug Discovery and Development. 1. John Wiley & Sons. 2006. pp. 203–205. ISBN 9780471780090. https://books.google.com/books?id=Bu5IHnBxjxwC&pg=PA203.

- ↑ Sweetman S., ed (2004). Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference (34th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85369-550-9.

- ↑ "Therapeutic potential of drugs with mixed 5-HT4 agonist/5-HT3 antagonist action in the control of emesis". Pharmacological Research 31 (5): 257–260. May 1995. doi:10.1016/1043-6618(95)80029-8. PMID 7479521.

- ↑ "Ch. 43: Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease". Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease (9th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. 2010. ISBN 978-1-4160-6189-2.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Drug Discovery: A History. John Wiley & Sons. 31 October 2005. pp. 205–. ISBN 978-0-470-01552-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=Cb6BOkj9fK4C&pg=PA130.

- ↑ "Translating 5-HT receptor pharmacology". Neurogastroenterology and Motility 21 (12): 1235–1238. December 2009. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01425.x. PMID 19906028.

- ↑ "[Antiemetic Action of Metoclopramide with Respect to Apomorphine and Hydergine]" (in fr). Comptes Rendus des Séances de la Société de Biologie et de ses Filiales 158: 723–727. 1964. PMID 14186927.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 "Metoclopramide for the Control of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting". Antiemetic Therapy. 2003. pp. 161–168. doi:10.1159/000071415. ISBN 3-8055-7547-5.

- ↑ Petite histoire des médicaments: De l'Antiquité à nos jours.. Dunod. 2011. p. 182. ISBN 9782100571307. https://books.google.com/books?id=MgLrCgAAQBAJ&pg=PT182.

- ↑ "La mystérieuse bonbonne des Laboratoires Delagrange [Q265, Usage des bonbonnes."]. Revue d'Histoire de la Pharmacie 94 (353): 160–162. 2007. http://www.persee.fr/doc/pharm_0035-2349_2007_num_94_353_6121.

- ↑ "Synthélabo rachète les laboratoires Delagrange". Lesechos.fr. 17 October 1991. http://www.lesechos.fr/17/10/1991/LesEchos/15996-035-ECH_synthelabo-rachete-les-laboratoires-delagrange.htm.

- ↑ "Laboratoires Delagrange (1932) - Organisation - Resources from the BnF". Data.bnf.fr. http://data.bnf.fr/12198004/laboratoires_delagrange/.

- ↑ "A look back at Sanofi's merger with Synthélabo". PMLiVE. Pmlive.com. 24 May 2013. http://www.pmlive.com/pharma_news/a_look_back_at_sanofis_merger_with_synthelabo_477146.

- ↑ "Metoclopramide hydrochloride". Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia. 1-4 (3rd ed.). Elsevier. 2013. pp. 179m. ISBN 9780815518563. https://books.google.com/books?id=_J2ti4EkYpkC&pg=PA2109-IA164.

- ↑ "New Drug Application (NDA): 017862 - Approval history - Hikma Metoclopramide Hydrochloride". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&varApplNo=017862.

- ↑ "New Drug Application (NDA): 017854: Approval history - Ani Pharms Metoclopramide Hydrochloride". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&varApplNo=017854.

- ↑ "Virginia Historical Society A Guide to the A. H. Robins Company Records, 1885–2004.". http://www.vahistorical.org/collections-and-resources/how-we-can-help-your-research/researcher-resources/finding-aids/ah-robins.

- ↑ "American Home Is Changing Name to Wyeth". The New York Times. 11 March 2002. https://www.nytimes.com/2002/03/11/business/american-home-is-changing-name-to-wyeth.html.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Staff (29 September 1986). "FDA's Oral Verapamil ANDA Approvals on Eve of Exclusivity Expiration Pit Five Generic Products V. Calan, Isoptin; Inderal, Reglan Indications No Longer Exclusive". The Pink Sheet. https://pink.pharmamedtechbi.com/PS010783/FDAs-ORAL-VERAPAMIL-ANDA-APPROVALS-ON-EVE-OF-EXCLUSIVITY-EXPIRATION-PIT-FIVE-GENERIC-PRODUCTS-v-CALAN-ISOPTIN-INDERAL-REGLAN-INDICATIONS-NO-LONGER-EXCLUSIVE.

- ↑ "All About Metoclopramide (Reglan)". Emergency Physicians Monthly. EPMonthly.com. 15 August 2014. http://epmonthly.com/article/all-about-metoclopramide-reglan/.

- ↑ "TEVA Metoclopramide Hydrochloride". Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA): 070184. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=070184.

- ↑ "Tardive dyskinesia associated with metoclopramide". British Medical Journal 288 (6416): 545–547. February 1984. doi:10.1136/bmj.288.6416.545. PMID 6421373.

- ↑ "Missing After Mensing: A Remedy for Generic Drug Consumers.". Boston College Law Review 53: 1967–2001. 2012. http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol53/iss5/9.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 "Generic Pharmaceutical Liability: Challenges And Changes". Law360. 24 October 2012. http://www.law360.com/articles/388965/generic-pharmaceutical-liability-challenges-and-changes.com

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 57.3 "Adding Insult to Injury: Paying For Harms Caused by a Competitor's Copycat Product". Tort Trial & Insurance Practice Law Journal 45 (3–4): 673–695. Spring–Summer 2010. http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/tort_insurance_law_journal/tips_vol45_no3_4_Noah.authcheckdam.pdf. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 58.3 "Calif. Asks Innovator Drug Brands To Do The Impossible". Pepper Hamilton LLP's Insight Center. 16 March 2016. http://www.pepperlaw.com/publications/calif-asks-innovator-drug-brands-to-do-the-impossible-2016-03-16/.

- ↑ Conte v. Wyeth, Inc., A116707, A117353 (Court of Appeal, First District, Division 3, California.).

- ↑ PLIVA, Inc. v. Mensing (U.S. Supreme Court 23 June 2011). Text

- ↑ "Drug Makers Win Two Supreme Court Decisions". The New York Times. 23 June 2011. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/24/business/24bizcourt.html.

- ↑ "FDA moves to make generic drugmakers more accountable". 8 November 2013. http://www.today.com/news/fda-moves-make-generic-drugmakers-more-accountable-8C11545187.

- ↑ "FDA delays rule to allow generic drug makers to change labels". Pharmalot. Statnews.com. 19 May 2016. https://www.statnews.com/pharmalot/2016/05/19/fda-generic-drugs-safety/.

- ↑ "Generic Drug Labels: FDA Offers Draft Guidance on Updates After Reference Products are Withdrawn". Regulatory Focus. 8 July 2016. http://raps.org/Regulatory-Focus/News/2016/07/08/25292/Generic-Drug-Labels-FDA-Offers-Draft-Guidance-on-Updates-After-Reference-Products-are-Withdrawn/.

- ↑ Tarascon Pharmacopoeia 2010 Library Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. 2010. p. 170. ISBN 9780763777685. https://books.google.com/books?id=Urmh7ylCXnoC&pg=PA170.

- ↑ "Anagraine - Drugs.com". https://www.drugs.com/international/anagraine.html.

- ↑ "Metoclopramide HCl". The Elephant Formulary. Elephant Care International. June 2003. http://www.elephantcare.org/Drugs/metoclop.htm.

External links

|