Biology:Estrogen receptor

| estrogen receptor 1 (ER-alpha) | |

|---|---|

A dimer of the ligand-binding region of ERα (PDB rendering based on 3erd). | |

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | ESR1 |

| Alt. symbols | ER-α, NR3A1 |

| NCBI gene | 2099 |

| HGNC | 3467 |

| OMIM | 133430 |

| PDB | 1ERE |

| RefSeq | NM_000125 |

| UniProt | P03372 |

| Other data | |

| Locus | Chr. 6 q24-q27 |

| estrogen receptor 2 (ER-beta) | |

|---|---|

| Error creating thumbnail: Unable to save thumbnail to destination | |

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | ESR2 |

| Alt. symbols | ER-β, NR3A2 |

| NCBI gene | 2100 |

| HGNC | 3468 |

| OMIM | 601663 |

| PDB | 1QKM |

| RefSeq | NM_001040275 |

| UniProt | Q92731 |

| Other data | |

| Locus | Chr. 14 q21-q22 |

Estrogen receptors (ERs) are a group of proteins found inside cells. They are receptors that are activated by the hormone estrogen (17β-estradiol).[1] Two classes of ER exist: nuclear estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ), which are members of the nuclear receptor family of intracellular receptors, and membrane estrogen receptors (mERs) (GPER (GPR30), ER-X, and Gq-mER), which are mostly G protein-coupled receptors. This article refers to the former (ER).

Once activated by estrogen, the ER is able to translocate into the nucleus and bind to DNA to regulate the activity of different genes (i.e. it is a DNA-binding transcription factor). However, it also has additional functions independent of DNA binding.[2]

As hormone receptors for sex steroids (steroid hormone receptors), ERs, androgen receptors (ARs), and progesterone receptors (PRs) are important in sexual maturation and gestation.

Proteomics

There are two different forms of the estrogen receptor, usually referred to as α and β, each encoded by a separate gene (ESR1 and ESR2, respectively). Hormone-activated estrogen receptors form dimers, and, since the two forms are coexpressed in many cell types, the receptors may form ERα (αα) or ERβ (ββ) homodimers or ERαβ (αβ) heterodimers.[3] Estrogen receptor alpha and beta show significant overall sequence homology, and both are composed of five domains designated A/B through F (listed from the N- to C-terminus; amino acid sequence numbers refer to human ER).[citation needed]

The N-terminal A/B domain is able to transactivate gene transcription in the absence of bound ligand (e.g., the estrogen hormone). While this region is able to activate gene transcription without ligand, this activation is weak and more selective compared to the activation provided by the E domain. The C domain, also known as the DNA-binding domain, binds to estrogen response elements in DNA. The D domain is a hinge region that connects the C and E domains. The E domain contains the ligand binding cavity as well as binding sites for coactivator and corepressor proteins. The E-domain in the presence of bound ligand is able to activate gene transcription. The C-terminal F domain function is not entirely clear and is variable in length.[citation needed]

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Due to alternative RNA splicing, several ER isoforms are known to exist. At least three ERα and five ERβ isoforms have been identified. The ERβ isoforms receptor subtypes can transactivate transcription only when a heterodimer with the functional ERß1 receptor of 59 kDa is formed. The ERß3 receptor was detected at high levels in the testis. The two other ERα isoforms are 36 and 46kDa.[4][5]

Only in fish, but not in humans, an ERγ receptor has been described.[6]

Genetics

In humans, the two forms of the estrogen receptor are encoded by different genes, ESR1 and ESR2 on the sixth and fourteenth chromosome (6q25.1 and 14q23.2), respectively.

Distribution

Both ERs are widely expressed in different tissue types, however there are some notable differences in their expression patterns:[7]

- The ERα is found in endometrium, breast cancer cells, ovarian stromal cells, and the hypothalamus.[8] In males, ERα protein is found in the epithelium of the efferent ducts.[9]

- The expression of the ERβ protein has been documented in ovarian granulosa cells, kidney, brain, bone, heart,[10] lungs, intestinal mucosa, prostate, and endothelial cells.

The ERs are regarded to be cytoplasmic receptors in their unliganded state, but visualization research has shown that only a small fraction of the ERs reside in the cytoplasm, with most ER constitutively in the nucleus.[11] The "ERα" primary transcript gives rise to several alternatively spliced variants of unknown function.[12]

Ligands

Agonists

- Endogenous estrogens (e.g., estradiol, estrone, estriol, estetrol)

- Natural estrogens (e.g., conjugated estrogens)

- Synthetic estrogens (e.g., ethinylestradiol, diethylstilbestrol)

Mixed (agonist and antagonist mode of action)

- Phytoestrogens (e.g., coumestrol, daidzein, genistein, miroestrol)

- Selective estrogen receptor modulators (e.g., tamoxifen, clomifene, raloxifene)

Antagonists

- Antiestrogens (e.g., fulvestrant, ICI-164384, ethamoxytriphetol)

Affinities

Binding and functional selectivity

The ER's helix 12 domain plays a crucial role in determining interactions with coactivators and corepressors and, therefore, the respective agonist or antagonist effect of the ligand.[13][14]

Different ligands may differ in their affinity for alpha and beta isoforms of the estrogen receptor:

- estradiol binds equally well to both receptors[15]

- estrone, and raloxifene bind preferentially to the alpha receptor[15]

- estriol, and genistein to the beta receptor[15]

Subtype selective estrogen receptor modulators preferentially bind to either the α- or the β-subtype of the receptor. In addition, the different estrogen receptor combinations may respond differently to various ligands, which may translate into tissue selective agonistic and antagonistic effects.[16] The ratio of α- to β- subtype concentration has been proposed to play a role in certain diseases.[17]

The concept of selective estrogen receptor modulators is based on the ability to promote ER interactions with different proteins such as transcriptional coactivator or corepressors. Furthermore, the ratio of coactivator to corepressor protein varies in different tissues.[18] As a consequence, the same ligand may be an agonist in some tissue (where coactivators predominate) while antagonistic in other tissues (where corepressors dominate). Tamoxifen, for example, is an antagonist in breast and is, therefore, used as a breast cancer treatment[19] but an ER agonist in bone (thereby preventing osteoporosis) and a partial agonist in the endometrium (increasing the risk of uterine cancer).

Signal transduction

Since estrogen is a steroidal hormone, it can pass through the phospholipid membranes of the cell, and receptors therefore do not need to be membrane-bound in order to bind with estrogen.[citation needed]

Genomic

In the absence of hormone, estrogen receptors are largely located in the cytosol. Hormone binding to the receptor triggers a number of events starting with migration of the receptor from the cytosol into the nucleus, dimerization of the receptor, and subsequent binding of the receptor dimer to specific sequences of DNA known as hormone response elements. The DNA/receptor complex then recruits other proteins that are responsible for the transcription of downstream DNA into mRNA and finally protein that results in a change in cell function. Estrogen receptors also occur within the cell nucleus, and both estrogen receptor subtypes have a DNA-binding domain and can function as transcription factors to regulate the production of proteins.[citation needed]

The receptor also interacts with activator protein 1 and Sp-1 to promote transcription, via several coactivators such as PELP-1.[2]

Direct acetylation of the estrogen receptor alpha at the lysine residues in hinge region by p300 regulates transactivation and hormone sensitivity.[20]

Non-genomic

Some estrogen receptors associate with the cell surface membrane and can be rapidly activated by exposure of cells to estrogen.[21][22]

In addition, some ER may associate with cell membranes by attachment to caveolin-1 and form complexes with G proteins, striatin, receptor tyrosine kinases (e.g., EGFR and IGF-1), and non-receptor tyrosine kinases (e.g., Src).[2][21] Through striatin, some of this membrane bound ER may lead to increased levels of Ca2+ and nitric oxide (NO).[23] Through the receptor tyrosine kinases, signals are sent to the nucleus through the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK/ERK) pathway and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (Pl3K/AKT) pathway.[24] Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK)-3β inhibits transcription by nuclear ER by inhibiting phosphorylation of serine 118 of nuclear ERα. Phosphorylation of GSK-3β removes its inhibitory effect, and this can be achieved by the PI3K/AKT pathway and the MAPK/ERK pathway, via rsk.[citation needed]

17β-Estradiol has been shown to activate the G protein-coupled receptor GPR30.[25] However the subcellular localization and role of this receptor are still object of controversy.[26]

Differences and malfunction

Cancer

Estrogen receptors are over-expressed in around 70% of breast cancer cases, referred to as "ER-positive", and can be demonstrated in such tissues using immunohistochemistry. Two hypotheses have been proposed to explain why this causes tumorigenesis, and the available evidence suggests that both mechanisms contribute:

- First, binding of estrogen to the ER stimulates proliferation of mammary cells, with the resulting increase in cell division and DNA replication, leading to mutations.

- Second, estrogen metabolism produces genotoxic waste.

The result of both processes is disruption of cell cycle, apoptosis and DNA repair, which increases the chance of tumour formation. ERα is certainly associated with more differentiated tumours, while evidence that ERβ is involved is controversial. Different versions of the ESR1 gene have been identified (with single-nucleotide polymorphisms) and are associated with different risks of developing breast cancer.[19]

Estrogen and the ERs have also been implicated in breast cancer, ovarian cancer, colon cancer, prostate cancer, and endometrial cancer. Advanced colon cancer is associated with a loss of ERβ, the predominant ER in colon tissue, and colon cancer is treated with ERβ-specific agonists.[27]

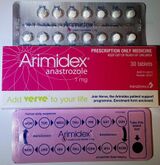

Endocrine therapy for breast cancer involves selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMS), such as tamoxifen, which behave as ER antagonists in breast tissue, or aromatase inhibitors, such as anastrozole. ER status is used to determine sensitivity of breast cancer lesions to tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors.[28] Another SERM, raloxifene, has been used as a preventive chemotherapy for women judged to have a high risk of developing breast cancer.[29] Another chemotherapeutic anti-estrogen, ICI 182,780 (Faslodex), which acts as a complete antagonist, also promotes degradation of the estrogen receptor.

However, de novo resistance to endocrine therapy undermines the efficacy of using competitive inhibitors like tamoxifen. Hormone deprivation through the use of aromatase inhibitors is also rendered futile.[30] Massively parallel genome sequencing has revealed the common presence of point mutations on ESR1 that are drivers for resistance, and promote the agonist conformation of ERα without the bound ligand. Such constitutive, estrogen-independent activity is driven by specific mutations, such as the D538G or Y537S/C/N mutations, in the ligand binding domain of ESR1 and promote cell proliferation and tumor progression without hormone stimulation.[31]

Menopause

The metabolic effects of estrogen in postmenopausal women has been linked to the genetic polymorphism of estrogen receptor beta (ER-β).[32]

Aging

Studies in female mice have shown that estrogen receptor-alpha declines in the pre-optic hypothalamus as they grow old. Female mice that were given a calorically restricted diet during the majority of their lives maintained higher levels of ERα in the pre-optic hypothalamus than their non-calorically restricted counterparts.[8]

Obesity

A dramatic demonstration of the importance of estrogens in the regulation of fat deposition comes from transgenic mice that were genetically engineered to lack a functional aromatase gene. These mice have very low levels of estrogen and are obese.[33] Obesity was also observed in estrogen deficient female mice lacking the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor.[34] The effect of low estrogen on increased obesity has been linked to estrogen receptor alpha.[35]

SERMs for other treatment purposes

SERMs are also being studied for the treatment of uterine fibroids[36] and endometriosis.[37]

Estrogen insensitivity syndrome

Estrogen insensitivity syndrome is a rare intersex condition with 5 reported cases, in which estrogen receptors do not function. The phenotype results in extensive masculinization. Unlike androgen insensitivity syndrome, EIS does not result in phenotype sex reversal. It is incredibly rare and is anologious to the AIS, and forms of adrenal hyperplasia. The reason why AIS is common and EIS is exceptionally rare is that XX AIS does not result in infertility, and therefore can be maternally inheirented, while EIS always results in infertility regardless of karyotype. A negative feedback loop between the endocrine system also occurs in EIS, in which the gonads produce markedly higher levels of estrogen for individuals with EIS (119–272 pg/mL XY and 750-3,500 pg/mL XX, see average levels) however no feminizing effects occur.[38][39]

Discovery

Estrogen receptors were first identified by Elwood V. Jensen at the University of Chicago in 1958,[40][41] for which Jensen was awarded the Lasker Award.[42] The gene for a second estrogen receptor (ERβ) was identified in 1996 by Kuiper et al. in rat prostate and ovary using degenerate ERalpha primers.[43]

See also

- Membrane estrogen receptor

- Estrogen insensitivity syndrome

- Aromatase deficiency

- Aromatase excess syndrome

References

- ↑ "International Union of Pharmacology. LXIV. Estrogen receptors". Pharmacological Reviews 58 (4): 773–81. Dec 2006. doi:10.1124/pr.58.4.8. PMID 17132854.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Integration of the extranuclear and nuclear actions of estrogen". Molecular Endocrinology 19 (8): 1951–9. Aug 2005. doi:10.1210/me.2004-0390. PMID 15705661.

- ↑ "Single-chain estrogen receptors (ERs) reveal that the ERalpha/beta heterodimer emulates functions of the ERalpha dimer in genomic estrogen signaling pathways". Molecular and Cellular Biology 24 (17): 7681–94. Sep 2004. doi:10.1128/MCB.24.17.7681-7694.2004. PMID 15314175.

- ↑ "Mechanisms of estrogen action". Physiological Reviews 81 (4): 1535–65. Oct 2001. doi:10.1152/physrev.2001.81.4.1535. PMID 11581496.

- ↑ "Estrogen receptor (ER)-beta isoforms: a key to understanding ER-beta signaling". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103 (35): 13162–7. Aug 2006. doi:10.1073/pnas.0605676103. PMID 16938840. Bibcode: 2006PNAS..10313162L.

- ↑ "Identification of a third distinct estrogen receptor and reclassification of estrogen receptors in teleosts". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97 (20): 10751–6. Sep 2000. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.20.10751. PMID 11005855. Bibcode: 2000PNAS...9710751H.

- ↑ "Tissue distribution and quantitative analysis of estrogen receptor-alpha (ERalpha) and estrogen receptor-beta (ERbeta) messenger ribonucleic acid in the wild-type and ERalpha-knockout mouse". Endocrinology 138 (11): 4613–21. Nov 1997. doi:10.1210/en.138.11.4613. PMID 9348186.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Caloric restriction reduces cell loss and maintains estrogen receptor-alpha immunoreactivity in the pre-optic hypothalamus of female B6D2F1 mice". Neuro Endocrinology Letters 26 (3): 197–203. Jun 2005. PMID 15990721. http://www.nel.edu/pdf_/26_3/260305A01_15990721_Yaghmaie_.pdf.

- ↑ "Estrogen in the adult male reproductive tract: a review". Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 1 (52): 52. Jul 2003. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-1-52. PMID 12904263.

- ↑ "Estrogenic hormone action in the heart: regulatory network and function". Cardiovascular Research 53 (3): 709–19. Feb 2002. doi:10.1016/S0008-6363(01)00526-0. PMID 11861041.

- ↑ "Direct visualization of the human estrogen receptor alpha reveals a role for ligand in the nuclear distribution of the receptor". Molecular Biology of the Cell 10 (2): 471–86. Feb 1999. doi:10.1091/mbc.10.2.471. PMID 9950689.

- ↑ "Coexpression of multiple estrogen receptor variant messenger RNAs in normal and neoplastic breast tissues and in MCF-7 cells". Cancer Research 55 (10): 2158–65. May 1995. PMID 7743517.

- ↑ "Structure-function relationship of estrogen receptor alpha and beta: impact on human health". Molecular Aspects of Medicine 27 (4): 299–402. Aug 2006. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2006.07.001. PMID 16914190.

- ↑ "Nuclear receptor ligand-binding domains: three-dimensional structures, molecular interactions and pharmacological implications". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 21 (10): 381–8. Oct 2000. doi:10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01548-0. PMID 11050318.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 "Quantitative structure-activity relationship of various endogenous estrogen metabolites for human estrogen receptor alpha and beta subtypes: Insights into the structural determinants favoring a differential subtype binding". Endocrinology 147 (9): 4132–50. Sep 2006. doi:10.1210/en.2006-0113. PMID 16728493.

- ↑ "Differential effects of estrogen receptor antagonists on pituitary lactotroph proliferation and prolactin release". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 239 (1–2): 27–36. Jul 2005. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2005.04.008. PMID 15950373.

- ↑ "Estrogen receptor alpha and beta in uterine fibroids: a basis for altered estrogen responsiveness". Fertility and Sterility 90 (5): 1878–85. Nov 2008. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.09.019. PMID 18166184. http://helios-eie.ekt.gr/EIE/handle/10442/7330.

- ↑ "Molecular determinants for the tissue specificity of SERMs". Science 295 (5564): 2465–8. Mar 2002. doi:10.1126/science.1068537. PMID 11923541. Bibcode: 2002Sci...295.2465S.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Estrogen receptors and human disease". The Journal of Clinical Investigation 116 (3): 561–70. Mar 2006. doi:10.1172/JCI27987. PMID 16511588.

- ↑ "Direct acetylation of the estrogen receptor alpha hinge region by p300 regulates transactivation and hormone sensitivity". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 276 (21): 18375–83. May 2001. doi:10.1074/jbc.M100800200. PMID 11279135.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Membrane estrogen receptor-alpha levels in MCF-7 breast cancer cells predict cAMP and proliferation responses". Breast Cancer Research 7 (1): R101–12. 2005. doi:10.1186/bcr958. PMID 15642158.

- ↑ "Estrogen receptor-dependent activation of AP-1 via non-genomic signalling". Nuclear Receptor 2 (1): 3. Jun 2004. doi:10.1186/1478-1336-2-3. PMID 15196329.

- ↑ "Striatin assembles a membrane signaling complex necessary for rapid, nongenomic activation of endothelial NO synthase by estrogen receptor alpha". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101 (49): 17126–31. Dec 2004. doi:10.1073/pnas.0407492101. PMID 15569929. Bibcode: 2004PNAS..10117126L.

- ↑ "Activation of the estrogen receptor through phosphorylation by mitogen-activated protein kinase". Science 270 (5241): 1491–4. Dec 1995. doi:10.1126/science.270.5241.1491. PMID 7491495. Bibcode: 1995Sci...270.1491K.

- ↑ "GPR30: A G protein-coupled receptor for estrogen". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 265-266: 138–42. Feb 2007. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2006.12.010. PMID 17222505.

- ↑ "G protein-coupled receptor 30 localizes to the endoplasmic reticulum and is not activated by estradiol". Endocrinology 149 (10): 4846–56. Oct 2008. doi:10.1210/en.2008-0269. PMID 18566127.

- ↑ "Evaluation of an estrogen receptor-beta agonist in animal models of human disease". Endocrinology 144 (10): 4241–9. Oct 2003. doi:10.1210/en.2003-0550. PMID 14500559.

- ↑ "Tamoxifen ("Nolvadex"): a review". Cancer Treatment Reviews 28 (4): 165–80. Aug 2002. doi:10.1016/s0305-7372(02)00036-1. PMID 12363457.

- ↑ "Selective estrogen-receptor modulators for primary prevention of breast cancer". Journal of Clinical Oncology 23 (8): 1644–55. Mar 2005. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.11.005. PMID 15755972.

- ↑ "The search for ESR1 mutations in breast cancer". Nature Genetics 45 (12): 1415–6. Dec 2013. doi:10.1038/ng.2831. PMID 24270445.

- ↑ "Endocrine-therapy-resistant ESR1 variants revealed by genomic characterization of breast-cancer-derived xenografts". Cell Reports 4 (6): 1116–30. Sep 2013. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2013.08.022. PMID 24055055.

- ↑ "Effect of estrogen receptor β A1730G polymorphism on ABCA1 gene expression response to postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy". Genetic Testing and Molecular Biomarkers 15 (1–2): 11–5. 2011. doi:10.1089/gtmb.2010.0106. PMID 21117950.

- ↑ "The aromatase knockout mouse presents with a sexually dimorphic disruption to cholesterol homeostasis". Endocrinology 144 (9): 3895–903. Sep 2003. doi:10.1210/en.2003-0244. PMID 12933663.

- ↑ "Estrogen deficiency, obesity, and skeletal abnormalities in follicle-stimulating hormone receptor knockout (FORKO) female mice". Endocrinology 141 (11): 4295–308. Nov 2000. doi:10.1210/endo.141.11.7765. PMID 11089565.

- ↑ "Obesity and disturbed lipoprotein profile in estrogen receptor-alpha-deficient male mice". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 278 (3): 640–5. Nov 2000. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2000.3827. PMID 11095962.

- ↑ Lingxia, X; Taixiang, W; Xiaoyan, C (2007). "Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (Serms) for Uterine Leiomyomas". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD005287. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd005287.pub2. PMID 17443581.

- ↑ van Hoesel, Maaike HT; Chen, Ya Li; Zheng, Ai; Wan, Qi; Mourad, Selma M (2021-05-11). Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group. ed. "Selective oestrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) for endometriosis" (in en). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2021 (5): CD011169. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011169.pub2. PMID 33973648.

- ↑ Thomas L. Lemke; David A. Williams (24 January 2012). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1392–. ISBN 978-1-60913-345-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=Sd6ot9ul-bUC&pg=PA1392.

- ↑ "Estrogen resistance caused by a mutation in the estrogen-receptor gene in a man". The New England Journal of Medicine 331 (16): 1056–61. October 1994. doi:10.1056/NEJM199410203311604. PMID 8090165.

- ↑ "The estrogen receptor: a model for molecular medicine" (abstract). Clinical Cancer Research 9 (6): 1980–9. Jun 2003. PMID 12796359. http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/9/6/1980.

- ↑ "A conversation with Elwood Jensen. Interview by David D. Moore". Annual Review of Physiology 74: 1–11. 2011. doi:10.1146/annurev-physiol-020911-153327. PMID 21888507.

- ↑ David Bracey, 2004 "UC Scientist Wins 'American Nobel' Research Award." University of Cincinnati press release.

- ↑ "Cloning of a novel receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 93 (12): 5925–30. Jun 1996. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.12.5925. PMID 8650195.

External links

- Estrogen Receptors at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- David S. Goodsell (2003-09-01). "Estrogen Receptor". Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics (RCSB). http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/static.do?p=education_discussion/molecule_of_the_month/pdb45_1.html.

|