Chemistry:Mestranol

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Enovid, Norinyl, Ortho-Novum, others |

| Other names | Ethinylestradiol 3-methyl ether; EEME; EE3ME; CB-8027; L-33355; RS-1044; 17α-Ethynylestradiol 3-methyl ether; 17α-Ethynyl-3-methoxyestra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17β-ol; 3-Methoxy-19-norpregna-1,3,5(10)-trien-20-yn-17β-ol |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| MedlinePlus | a601050 |

| Routes of administration | By mouth[1] |

| Drug class | Estrogen; Estrogen ether |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolites | Ethinylestradiol |

| Elimination half-life | Mestranol: 50 min[2] EE: 7–36 hours[3][4][5][6] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H26O2 |

| Molar mass | 310.437 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Mestranol, sold under the brand names Enovid, Norinyl, and Ortho-Novum among others, is an estrogen medication which has been used in birth control pills, menopausal hormone therapy, and the treatment of menstrual disorders.[1][7][8][9] It is formulated in combination with a progestin and is not available alone.[9] It is taken by mouth.[1]

Side effects of mestranol include nausea, breast tension, edema, and breakthrough bleeding among others.[10] It is an estrogen, or an agonist of the estrogen receptors, the biological target of estrogens like estradiol.[11] Mestranol is a prodrug of ethinylestradiol in the body.[11]

Mestranol was discovered in 1956 and was introduced for medical use in 1957.[12][13] It was the estrogen component in the first birth control pill.[12][13] In 1969, mestranol was replaced by ethinylestradiol in most birth control pills, although mestranol continues to be used in a few birth control pills even today.[14][9] Mestranol remains available only in a few countries, including the United States , United Kingdom , Japan , and Chile .[9]

Medical uses

Mestranol was employed as the estrogen component in many of the first oral contraceptives, such as mestranol/noretynodrel (brand name Enovid) and mestranol/norethisterone (brand names Ortho-Novum, Norinyl), and is still in use today.[7][8][9] In addition to its use as an oral contraceptive, mestranol has been used as a component of menopausal hormone therapy for the treatment of menopausal symptoms.[1]

Side effects

Pharmacology

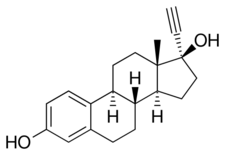

Mestranol is a biologically inactive prodrug of ethinylestradiol to which it is demethylated in the liver (via O-Dealkylation) with a conversion efficiency of 70% (50 μg of mestranol is pharmacokinetically bioequivalent to 35 μg of ethinylestradiol).[15][16][11] It has been found to possess 0.1 to 2.3% of the relative binding affinity of estradiol (100%) for the estrogen receptor, compared to 75 to 190% for ethinylestradiol.[17][18]

The elimination half-life of mestranol has been reported to be 50 minutes.[2] The elimination half-life of the active form of mestranol, ethinylestradiol, is 7 to 36 hours.[3][4][5][6]

The effective ovulation-inhibiting dosage of mestranol has been studied in women.[19][20][21] It has been reported to be about 98% effective at inhibiting ovulation at a dosage of 75 or 80 μg/day.[22][21][23] In another study, the ovulation rate was 15.4% at 50 μg/day, 5.7% at 80 μg/day, and 1.1% at 100 μg/day.[24]

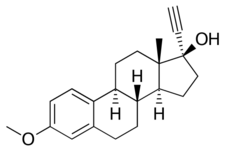

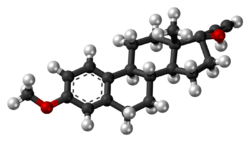

Chemistry

Mestranol, also known as ethinylestradiol 3-methyl ether (EEME) or as 17α-ethynyl-3-methoxyestra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17β-ol, is a synthetic estrane steroid and a derivative of estradiol.[25][26][27] It is specifically a derivative of ethinylestradiol (17α-ethynylestradiol) with a methyl ether at the C3 position.[25][26]

History

In April 1956, noretynodrel was investigated, in Puerto Rico, in the first large-scale clinical trial of a progestogen as an oral contraceptive.[12][13] The trial was conducted in Puerto Rico due to the high birth rate in the country and concerns of moral censure in the United States.[28] It was discovered early into the study that the initial chemical syntheses of noretynodrel had been contaminated with small amounts (1–2%) of the 3-methyl ether of ethinylestradiol (noretynodrel having been synthesized from ethinylestradiol).[12][13] When this impurity was removed, higher rates of breakthrough bleeding occurred.[12][13] As a result, mestranol, that same year (1956),[29] was developed and serendipitously identified as a very potent synthetic estrogen (and eventually as a prodrug of ethinylestradiol), given its name, and added back to the formulation.[12][13] This resulted in Enovid by G. D. Searle & Company, the first oral contraceptive and a combination of 9.85 mg noretynodrel and 150 μg mestranol per pill.[12][13]

Around 1969, mestranol was replaced by ethinylestradiol in most combined oral contraceptives due to widespread panic about the recently uncovered increased risk of venous thromboembolism with estrogen-containing oral contraceptives.[14] The rationale was that ethinylestradiol was approximately twice as potent by weight as mestranol and hence that the dose could be halved, which it was thought might result in a lower incidence of venous thromboembolism.[14] Whether this actually did result in a lower incidence of venous thromboembolism has never been assessed.[14]

Society and culture

Generic names

Mestranol is the generic name of the drug and its INN, USAN, USP, BAN, DCF, and JAN, while mestranolo is its DCIT.[25][26][1][9]

Brand names

Mestranol has been marketed under a variety of brand names, mostly or exclusively in combination with progestins, including Devocin, Enavid, Enovid, Femigen, Mestranol, Norbiogest, Ortho-Novin, Ortho-Novum, Ovastol, and Tranel among others.[7][25][30][26] Today, it continues to be sold in combination with progestins under brand names including Lutedion, Necon, Norinyl, Ortho-Novum, and Sophia.[9]

Availability

Mestranol remains available only in the United States , the United Kingdom , Japan , and Chile .[9] It is only marketed in combination with progestins, such as norethisterone.[9]

Research

Mestranol has been studied as a male contraceptive and was found to be highly effective.[31][32][33][34] At a dosage of 0.45 mg/day, it suppressed gonadotropin levels, reduced sperm count to zero within 4 to 6 weeks, and decreased libido, erectile function, and testicular size.[31][32][34][33] Gynecomastia occurred in all of the men.[31][32][34][33] These findings contributed to the conclusion that estrogens would be unacceptable as contraceptives for men.[32]

Environmental presence

In 2021, mestranol was one of the 12 compounds identified in sludge samples taken from 12 wastewater treatment plants in California that were collectively associated with estrogenic activity in in vitro. [35]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. 6 December 2012. pp. 177–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=tsjrCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA177.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Gynäkologische Endokrinologie und Fortpflanzungsmedizin: Band 1: Gynäkologische Endokrinologie. Springer-Verlag. 17 April 2013. pp. 88–. ISBN 978-3-662-07635-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=mBF9BwAAQBAJ&pg=PA88.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Translational Toxicology: Defining a New Therapeutic Discipline. Humana Press. 23 March 2016. pp. 73–. ISBN 978-3-319-27449-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=5qPWCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA73.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Pharmacokinetics of ethinyl estradiol and mestranol". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 163 (6 Pt 2): 2114–2119. December 1990. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(90)90550-Q. PMID 2256522.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Ethinyl estradiol and 17β-estradiol in combined oral contraceptives: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and risk assessment". Contraception 87 (6): 706–727. June 2013. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2012.12.011. PMID 23375353.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Pharmacology of estrogens". The Climacteric in Perspective. Springer. 1986. pp. 393–410. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-4145-8_36. ISBN 978-94-010-8339-3.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Sexual Chemistry: A History of the Contraceptive Pill. Yale University Press. 2010. pp. 75–. ISBN 978-0-300-16791-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=_i-s4biQs7MC&pg=PA75.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Adolescent Health Care: Clinical Issues. Elsevier Science. 22 October 2013. pp. 216–. ISBN 978-1-4832-7738-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=36PpAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA216.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 "Mestranol and norethindrone Uses, Side Effects & Warnings". https://www.drugs.com/international/mestranol.html.

- ↑ "Clinical Effects of Estrogens". Functional Morphologic Changes in Female Sex Organs Induced by Exogenous Hormones. Springer. 1980. pp. 67–71. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-67568-3_10. ISBN 978-3-642-67570-6.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 The Handbook of Contraception: A Guide for Practical Management. Springer Science & Business Media. 7 November 2007. pp. 23–. ISBN 978-1-59745-150-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=sczb0Tk_2IwC&pg=PA23. "EE is about 1.7 times as potent as the same weight of mestranol."

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 Drug Discovery: A History. John Wiley & Sons. 23 June 2005. pp. 202–. ISBN 978-0-471-89979-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=Cb6BOkj9fK4C&pg=PA202.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 Comprehensive Gynecology. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2012. pp. 224–. ISBN 978-0-323-06986-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=OmpULog7A_QC&pg=PA224.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Meyler's Side Effects of Endocrine and Metabolic Drugs. Elsevier. 21 February 2009. pp. 224–. ISBN 978-0-08-093292-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=BWMeSwVwfTkC&pg=PA224.

- ↑ "Pharmacokinetics of estrogens and progestogens". Estrogens and Progestogens in Clinical Practice. London: Churchill Livingstone. 1998. pp. 273–294. ISBN 0-443-04706-5.

- ↑ Clinical Reproductive Medicine and Surgery. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2007. pp. 388–. ISBN 978-0-323-03309-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=fOPtaEIKvcIC&pg=PA388.

- ↑ "The estrogen receptor relative binding affinities of 188 natural and xenochemicals: structural diversity of ligands". Toxicological Sciences 54 (1): 138–153. March 2000. doi:10.1093/toxsci/54.1.138. PMID 10746941.

- ↑ "Female Sex Hormones, Contraceptives, And Fertility Drugs". Burger's Medicinal Chemistry and Drug Discovery. Wiley. 2010. pp. 219–264. doi:10.1002/0471266949.bmc054. ISBN 978-0471266945.

- ↑ "Oral contraceptives: therapeutics versus adverse reactions, with an outlook for the future I". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 62 (2): 179–200. February 1973. doi:10.1002/jps.2600620202. PMID 4568621.

- ↑ The Control of Fertility. Elsevier. 3 September 2013. pp. 222–. ISBN 978-1-4832-7088-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=ehQlBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA222.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Antiovulatory Activity of Several Synthetic and Natural Estrogens". Ovulation: Stimulation, Suppression, and Detection. Lippincott. 1966. pp. 243–253. ISBN 9780397590100. https://books.google.com/books?id=le1qAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ "Physiology and pharmacology of female reproduction under the aspect of fertility control". Reviews of Physiology Biochemistry and Experimental Pharmacology, Volume 67. Ergebnisse der Physiologie Reviews of Physiology. 67. 1972. pp. 69–168. doi:10.1007/BFb0036328. ISBN 3-540-05959-8.

- ↑ "Biological Properties of Estrogen Sulfates". Chemical and Biological Aspects of Steroid Conjugation. Springer. 1970. pp. 368–408. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-49793-3_8. ISBN 978-3-642-49506-9.

- ↑ "Comparative studies of the ethynyl estrogens used in oral contraceptives. II. Antiovulatory potency". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 122 (5): 619–624. July 1975. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(75)90061-7. PMID 1146927.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. 14 November 2014. pp. 775–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=0vXTBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA775.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 656–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=5GpcTQD_L2oC&pg=PA656.

- ↑ Clinical Endocrinology: Theory and Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. 6 December 2012. pp. 575–. ISBN 978-3-642-96158-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=DAgJCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA575.

- ↑ Contraception: Science and Practice. Elsevier Science. 22 October 2013. pp. 12–. ISBN 978-1-4831-6366-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ug3-BAAAQBAJ&pg=PA12.

- ↑ "Lactation suppression utilizing norethynodrel with mestranol". The Journal of the Florida Medical Association 56 (2): 95–97. February 1969. PMID 4884828.

- ↑ Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). Elsevier. 22 October 2013. pp. 2109–. ISBN 978-0-8155-1856-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=_J2ti4EkYpkC&pg=PA2109-IA88.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 "Pharmacology of estrogens-general". Pharmacology & Therapeutics 9 (1): 107–119. 1980. doi:10.1016/0163-7258(80)90018-2. PMID 6771777.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 "Progress towards a male oral contraceptive". Clinics in Endocrinology and Metabolism 4 (3): 643–663. November 1975. doi:10.1016/S0300-595X(75)80051-X. PMID 776453.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 "Estrogens and Antiestrogens in the Male". Estrogens and Antiestrogens II: Pharmacology and Clinical Application of Estrogens and Antiestrogen. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 135 / 2. Springer Science & Business Media. 1999. pp. 505–571. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-60107-1_25. ISBN 978-3-642-60107-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=wBvyCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA538.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 "Effects of progesterone and synthetic progestins on the reproductive physiology of normal men". Federation Proceedings 18: 1057–1065. December 1959. PMID 14400846. https://www.popline.org/node/472874.

- ↑ "Using Estrogenic Activity and Nontargeted Chemical Analysis to Identify Contaminants in Sewage Sludge". Environmental Science & Technology 55 (10): 6729–6739. May 2021. doi:10.1021/acs.est.0c07846. PMID 33909413. Bibcode: 2021EnST...55.6729B.

|