Chemistry:Prazepam

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

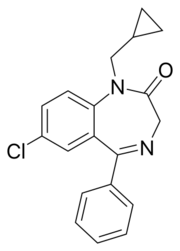

| Other names | 9-chloro-2-(cyclopropylmethyl)-6-phenyl-2,5-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undeca-5,8,10,12-tetraen- 3-one |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| MedlinePlus | a601036 |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 36–200 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C19H17ClN2O |

| Molar mass | 324.81 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Prazepam is a benzodiazepine derivative drug developed by Warner-Lambert in the 1960s.[1] It possesses anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, sedative and skeletal muscle relaxant properties.[2] Prazepam is a prodrug for desmethyldiazepam which is responsible for the therapeutic effects of prazepam.[3]

Indications

Prazepam is indicated for the short-term treatment of anxiety. After short-term therapy, the dose is usually gradually tapered-off to reduce or avoid any withdrawal or rebound effects.[4][5] Desmethyldiazepam, an active metabolite, has a very long half-life of 29 to 224 hours, which contributes to the therapeutic effects of prazepam.[6][7]

Side effects

Side effects of prazepam are less profound than with other benzodiazepines.[8] Excessive drowsiness and with longer-term use, drug dependence, are the most common side effects of prazepam.[9][10] Side effects such as fatigue or "feeling spacey" can also occur but less commonly than with other benzodiazepines. Other side effects include feebleness, clumsiness or lethargy, clouded thinking and mental slowness.[11][12][13]

Tolerance, dependence and withdrawal

Tolerance and dependence can develop with long-term use of prazepam, and upon cessation or reduction in dosage, then a benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome may occur with symptoms such as tremulousness, dysphoria, psychomotor agitation, tachycardia and sweating. In severe cases, hallucinations, psychosis and seizures can occur. Withdrawal-related psychosis is generally unresponsive to antipsychotic mediations. The risk and severity of the withdrawal syndrome increases the higher the dose and the longer prazepam is taken for.[14] Tolerance, dependence and withdrawal problems may be less severe than with other benzodiazepines, such as diazepam.[15] It may be because tolerance is slower to develop with prazepam than with other benzodiazepines.[16] Abrupt or over-rapid discontinuation of prazepam after long-term use, even at low dosage, may result in a protracted withdrawal syndrome.[17]

Benzodiazepines can induce serious problems of addiction, which is one of the main reasons for their use being restricted to short-term use. A survey in Senegal found that the majority of doctors believed that their training in this area was generally poor. It was recommended that national authorities take urgent action regarding the rational use of benzodiazepines. Almost one-fifth of doctors ignored prescription guidelines regarding short-term use of benzodiazepines, and almost three-quarters of doctors regarded their training and knowledge of benzodiazepines to be inadequate. More training regarding benzodiazepines has been recommended for doctors.[18][19]

Contraindications and special caution

Benzodiazepines require special precaution if used in the elderly, during pregnancy, in children, alcohol or drug-dependent individuals and individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders.[20]

Mechanism of action

Prazepam exerts its therapeutic effects primarily via modulating the benzodiazepine receptor which in turn enhances GABA function in the brain.[21] Prazepam like other benzodiazepines has anticonvulsant properties, but its anticonvulsant properties are not as potent as other benzodiazepines when tested in animal studies.[22][23][24][25]

Pharmacokinetics

Prazepam is metabolised into descyclopropylmethylprazepam (also known as desmethyldiazepam) and 3-hydroxyprazepam which is further metabolised into oxazepam.[26][27][28][29][30] Prazepam is a prodrug for descyclopropylmethylprazepam/desmethyldiazepam (also known as norprazepam or nordazepam) which is responsible for most of the therapeutic activity of prazepam rather than prazepam itself.[14][21][31][32]

Interactions

Prazepam may interact with cimetidine.[33] Alcohol in combination with prazepam increases the adverse effects, particularly performance impairing side effects and drowsiness.[34]

Overdose

The symptoms of an overdose of prazepam include sleepiness, agitation and ataxia. Hypotonia may also occur in severe cases. Overdoses in children typically result in more severe symptoms of overdose.[35]

Abuse potential

Prazepam like other benzodiazepines has abuse potential and can be habit forming. However, its abuse potential may be lower than other benzodiazepines because it has a slow onset of action.[14][36]

Toxicity

Animal studies have found prazepam taken during pregnancy results in delayed growth and causes reproductive abnormalities.[37][38][39]

Trade names

Common trade names include Centrac, Centrax, Demetrin, Lysanxia, Mono Demetrin, Pozapam, Prasepine, Prazene, Reapam and Trepidan. Trade names vary depending on the country; Austria: Demetrin, Belgium: Lysanxia, France : Lysanxia, Germany : Demetrin; Mono Demetrin, Greece: Centrac, Ireland: Centrax, Italy: Prazene; Trepidan, Macedonia: Demetrin, Prazepam, Netherlands: Reapam, Portugal: Demetrin, South Africa : Demetrin, Switzerland : Demetrin, Thailand: Pozapam; Prasepine.[40]

See also

- Benzodiazepine

- Benzodiazepine dependence

- Long-term effects of benzodiazepines

References

- ↑ US Patent 3192199 – Process for the production of I-CYCLO- ALKYL derivatives of I,X-BENZODIAZEPINE

- ↑ "Benzodiazepines: some aspects of their clinical pharmacology". Ciba Foundation Symposium. Novartis Foundation Symposia 1979 (74): 141–155. 1979. doi:10.1002/9780470720578.ch9. ISBN 9780470720578. PMID 45081.

- ↑ "Comparison of sublingual and oral prazepam in normal subjects. II. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data". Neuropsychobiology 19 (4): 186–191. 1988. doi:10.1159/000118458. PMID 2854609.

- ↑ "Prazepam in anxiety: a controlled clinical trial". Comprehensive Psychiatry 18 (3): 239–249. 1977. doi:10.1016/0010-440X(77)90018-9. PMID 858240.

- ↑ "[Value of prazepam drops in the brief treatment of anxiety disorders]" (in fr). L'Encephale 17 (4): 291–294. 1991. PMID 1959497.

- ↑ "Pharmacokinetics of benzodiazepines. Short-acting versus long-acting". Arzneimittel-Forschung 30 (5a): 875–881. 1980. PMID 6106488.

- ↑ "Desmethyldiazepam kinetics in the elderly after oral prazepam". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 28 (2): 196–202. August 1980. doi:10.1038/clpt.1980.150. PMID 6772370.

- ↑ "Comparative single-dose kinetics and dynamics of lorazepam, alprazolam, prazepam, and placebo". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 44 (3): 326–334. September 1988. doi:10.1038/clpt.1988.158. PMID 3138056.

- ↑ "[Treatment of anxiety with prazepam, 40 mg. A controlled study versus lorazepam]" (in fr). L'Encephale 10 (3): 135–138. 1984. PMID 6389091.

- ↑ "[Prescription and use of benzodiazepins in Saint-Louis in Senegal: patient survey]" (in fr). Annales Pharmaceutiques Françaises 62 (2): 133–137. March 2004. doi:10.1016/S0003-4509(04)94292-7. PMID 15107731.

- ↑ "Plasma concentrations and clinical effects after single oral doses of prazepam, clorazepate, and diazepam". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 45 (10): 411–413. October 1984. PMID 6148339.

- ↑ "Comparison of sublingual and oral prazepam in normal subjects. I. Clinical data". Neuropsychobiology 18 (2): 77–82. 1987. doi:10.1159/000118397. PMID 3330182.

- ↑ "[Prazepam drops versus 10 mg prazepam tablets in anxious patients in ambulatory care]" (in fr). Therapie 45 (6): 467–470. 1990. PMID 2080484.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 "The use of benzodiazepines in clinical practice". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 11 11 (Suppl 1): 5S–9S. 1981. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1981.tb01832.x. PMID 6133535.

- ↑ "A multi-centre comparison of prazepam and diazepam in the treatment of anxiety". Pharmatherapeutica 3 (6): 433–440. 1983. PMID 6353434.

- ↑ "Clinical symptomatology and computer analyzed EEG before, during and after anxiolytic therapy of alcohol withdrawal patients". Neuropsychobiology 9 (2–3): 119–134. 1983. doi:10.1159/000117949. PMID 6353268.

- ↑ "[Exacerbation of an affective psychosis after terminating a decade of benzodiazepine treatment. Which therapeutic procedure is sensible?]" (in de). Der Nervenarzt 65 (9): 628–632. September 1994. PMID 7991010.

- ↑ "Benzodiazepines prescription in Dakar: a study about prescribing habits and knowledge in general practitioners, neurologists and psychiatrists". Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology 20 (3): 235–238. June 2006. doi:10.1111/j.1472-8206.2006.00400.x. PMID 16671957.

- ↑ "Prescription des benzodiazépines par les médecins généralistes du privé à Dakar : Enquête sur les connaissances et les attitudes" (in fr). Therapie 62 (2): 163–168. 2007. doi:10.2515/therapie:2007018. PMID 17582318.

- ↑ "Benzodiazepine dependence: focus on withdrawal syndrome". Annales Pharmaceutiques Françaises 67 (6): 408–413. November 2009. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2009.07.001. PMID 19900604.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "[Molecular mechanism of action of benzodiazepines]" (in de). Fortschritte der Medizin 99 (20): 788–794. May 1981. PMID 6114911.

- ↑ "1,4-Benzodiazepine derivatives as anticonvulsant agents in DBA/2 mice". General Pharmacology 27 (6): 935–941. September 1996. doi:10.1016/0306-3623(95)02147-7. PMID 8909973.

- ↑ "Azirino[1, 2-d][1, 4]benzodiazepine derivatives and related 1,4-benzodiazepines as anticonvulsant agents in DBA/2 mice". General Pharmacology 27 (7): 1155–1162. October 1996. doi:10.1016/S0306-3623(96)00049-3. PMID 8981061.

- ↑ "Anticonvulsant activity of azirino[1,2-d][1,4]benzodiazepines and related 1,4-benzodiazepines in mice". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior 58 (1): 281–289. September 1997. doi:10.1016/S0091-3057(96)00565-5. PMID 9264104.

- ↑ "Anticonvulsant properties of 1,4-benzodiazepine derivatives in amygdaloid-kindled seizures and their chemical structure-related anticonvulsant action". Pharmacology 57 (5): 233–241. November 1998. doi:10.1159/000028247. PMID 9742288.

- ↑ "Prazepam metabolism after chronic administration to humans". Xenobiotica; the Fate of Foreign Compounds in Biological Systems 3 (9): 581–587. September 1973. doi:10.3109/00498257309151546. PMID 4763144.

- ↑ "Development and validation of a liquid chromatographic/electrospray ionization mass spectrometric method for the quantitation of prazepam and its main metabolites in human plasma". Journal of Mass Spectrometry 40 (4): 516–526. April 2005. doi:10.1002/jms.824. PMID 15712230. Bibcode: 2005JMSp...40..516V.

- ↑ "Stereoselective metabolism of prazepam and halazepam by human liver microsomes". Drug Metabolism and Disposition 19 (3): 637–642. 1991. PMID 1680631. http://dmd.aspetjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/19/3/637.

- ↑ "Prazepam, a precursor of desmethyldiazepam". Lancet 1 (8066): 720. April 1978. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(78)90834-6. PMID 76260.

- ↑ "Quantitative analysis of prazepam and its metabolites by electron capture gas chromatography and selected ion monitoring. Application to diaplacetal passage and fetal hepatic metabolism in early human pregnancy". Journal of Chromatography 146 (2): 227–239. September 1978. doi:10.1016/S0378-4347(00)81889-7. PMID 701422.

- ↑ "[Pharmacokinetics of oral prazepam]" (in de). Fortschritte der Medizin 99 (22): 874–879. June 1981. PMID 6790396.

- ↑ "Comparative single-dose kinetics of oxazolam, prazepam, and clorazepate: three precursors of desmethyldiazepam". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 24 (10): 446–451. October 1984. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1984.tb01817.x. PMID 6150943. http://jcp.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/24/10/446.

- ↑ "Cimetidine-benzodiazepine drug interaction". American Journal of Hospital Pharmacy 38 (9): 1365–1366. September 1981. PMID 6116430.

- ↑ "Comparison of performance of healthy volunteers given prazepam alone or combined with ethanol. Relation to drug plasma concentrations". International Clinical Psychopharmacology 6 (4): 227–238. 1991. doi:10.1097/00004850-199100640-00004. PMID 1816280.

- ↑ "Acute poisonings with ethyle loflazepate, flunitrazepam, prazepam and triazolam in children". Veterinary and Human Toxicology 34 (2): 141–143. April 1992. PMID 1354907.

- ↑ "[The habit-forming effect of prazepam]" (in pl). Psychiatria Polska 20 (3): 232–234. 1986. PMID 3797537.

- ↑ "Effect of benzodiazepines on age of vaginal perforation and first estrus in mice". Research Communications in Chemical Pathology and Pharmacology 21 (1): 181–184. July 1978. PMID 28555.

- ↑ "Benzodiazepines and reproduction of swiss-webster mice". Research Communications in Chemical Pathology and Pharmacology 13 (4): 601–610. April 1976. PMID 4863.

- ↑ "Benzodiazepine-induced suppression of estrous cycles in C57BL/6J mice". Research Communications in Chemical Pathology and Pharmacology 11 (1): 155–158. May 1975. PMID 239442.

- ↑ "Benzodiazepine Names". non-benzodiazepines.org.uk. http://www.non-benzodiazepines.org.uk/benzodiazepine-names.html.

External links

|