Chemistry:Midazolam

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /mɪˈdæzəlæm/ |

| Trade names | Dormicum, Hypnovel, Versed, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a609003 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intramuscular, intravenous, buccal, intranasal |

| Drug class | Benzodiazepine |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | By mouth (variable, around 40%)[4][5] intramuscular 90%+ |

| Protein binding | 97% |

| Metabolism | Liver 3A3, 3A4, 3A5 |

| Onset of action | Within 5 min (IV), 15 min (IM), 20 min (oral)[6] |

| Elimination half-life | 1.5–2.5 hours[7] |

| Duration of action | 1 to 6 hrs[6] |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

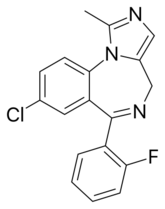

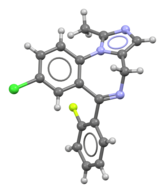

| Formula | C18H13ClFN3 |

| Molar mass | 325.77 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Midazolam, sold under the brand name Versed among others, is a benzodiazepine medication used for anesthesia and procedural sedation, and to treat severe agitation.[6] It induces sleepiness, decreases anxiety, and causes anterograde amnesia.[6]

The drug does not cause an individual to become unconscious, merely to be sedated.[6] It is also useful for the treatment of prolonged (lasting over 5 minutes) seizures.[8] Midazolam can be given by mouth, intravenously, by injection into a muscle, by spraying into the nose, or through the cheek.[6][8] When given intravenously, it typically begins working within five minutes; when injected into a muscle, it can take fifteen minutes to begin working.[6] Effects last between one and six hours.

Side effects can include a decrease in efforts to breathe, low blood pressure, and sleepiness.[6] Tolerance to its effects and withdrawal syndrome may occur following long-term use.[9] Paradoxical effects, such as increased activity, can occur especially in children and older people.[9] There is evidence of risk when used during pregnancy but no evidence of harm with a single dose during breastfeeding.[10][11] Like other benzodiazepines, it works by increasing the activity of the GABA neurotransmitter in the brain.

Midazolam was patented in 1974 and came into medical use in 1982.[12] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[13] Midazolam is available as a generic medication.[10] In many countries, it is a controlled substance.[6]

Medical uses

Seizures

Midazolam is sometimes used for the acute management of prolonged seizures. Long-term use for the management of epilepsy is not recommended due to the significant risk of tolerance (which renders midazolam and other benzodiazepines ineffective) and the significant side effect of sedation.[14] A benefit of midazolam is that in children it can be given in the cheek or in the nose for acute seizures, including status epilepticus.[15][16] Midazolam is effective for status epilepticus or when intravenous access cannot be obtained, and has advantages of being water-soluble, having a rapid onset of action and not causing metabolic acidosis from the propylene glycol vehicle (which is not required due to its solubility in water), which occurs with other benzodiazepines.[citation needed]

Drawbacks include a high degree of breakthrough seizures—due to the short half-life of midazolam—in over 50% of people treated, as well as treatment failure in 14–18% of people with refractory status epilepticus. Tolerance develops rapidly to the anticonvulsant effect, and the dose may need to be increased by several times to maintain anticonvulsant therapeutic effects. With prolonged use, tolerance and tachyphylaxis can occur and the elimination half-life may increase, up to days.[9][17] Buccal and intranasal midazolam may be both easier to administer and more effective than rectally administered diazepam in the emergency control of seizures.[18][19][20]

Procedural sedation

Intravenous midazolam is indicated for procedural sedation (often in combination with an opioid, such as fentanyl), preoperative sedation, for the induction of general anesthesia, and for sedation of people who are ventilated in critical care units.[21][22] Midazolam is superior to diazepam in impairing memory of endoscopy procedures, but propofol has a quicker recovery time and a better memory-impairing effect.[23] It is the most popular benzodiazepine in the intensive care unit (ICU) because of its short elimination half-life, combined with its water solubility and its suitability for continuous infusion. However, for long-term sedation, lorazepam is preferred due to its long duration of action,[24] and propofol has advantages over midazolam when used in the ICU for sedation, such as shorter weaning time and earlier tracheal extubation.[25]

Midazolam is sometimes used in neonatal intensive care units. When used, additional caution is required in newborns; midazolam should not be used for longer than 72 hours due to risks of tachyphylaxis, and the possibility of development of a benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome, as well as neurological complications. Bolus injections should be avoided due to the increased risk of cardiovascular depression, as well as neurological complications.[26] Midazolam is also sometimes used in newborns who are receiving mechanical ventilation, although morphine is preferred, owing to its better safety profile for this indication.[27]

Sedation using midazolam can be used to relieve anxiety and manage behaviour in children undergoing dental treatment.[28]

Agitation

Midazolam, in combination with an antipsychotic drug, is indicated for the acute management of schizophrenia when it is associated with aggressive or out-of-control behaviour.[29]

End of life care

In the final stages of end-of-life care, midazolam is routinely used at low doses via subcutaneous injection to help with agitation, restlessness or anxiety in the last hours or days of life.[30] At higher doses during the last weeks of life, midazolam is considered a first line agent in palliative continuous deep sedation therapy when it is necessary to alleviate intolerable suffering not responsive to other treatments,[31] but the need for this is rare.[32]

Administration

Routes of administration of midazolam can be oral, intranasal, buccal, intravenous, and intramuscular.

| Perioperative use | 0.15 to 0.40 mg/kg IV |

| Premedication | 0.07 to 0.10 mg/kg IM |

| Intravenous sedation | 0.05 to 0.15 mg/kg IV |

Contraindications

Benzodiazepines require special precaution if used in the elderly, during pregnancy, in children, in alcohol- or other drug-dependent individuals or those with comorbid psychiatric disorders.[33] Additional caution is required in critically ill patients, as accumulation of midazolam and its active metabolites may occur.[34] Kidney or liver impairments may slow down the elimination of midazolam leading to prolonged and enhanced effects.[35][36] Contraindications include hypersensitivity, acute narrow-angle glaucoma, shock, hypotension, or head injury. Most are relative contraindications.

Side effects

Side effects of midazolam in the elderly are listed above.[9] People experiencing amnesia as a side effect of midazolam are generally unaware their memory is impaired, unless they had previously known it as a side effect.[37]

Long-term use of benzodiazepines has been associated with long-lasting deficits in memory, and show only partial recovery six months after stopping benzodiazepines.[9] It is unclear whether full recovery occurs after longer periods of abstinence. Benzodiazepines can cause or worsen depression.[9] Paradoxical excitement occasionally occurs with benzodiazepines, including a worsening of seizures. Children and elderly individuals or those with a history of excessive alcohol use and individuals with a history of aggressive behavior or anger are at increased risk of paradoxical effects.[9] Paradoxical reactions are particularly associated with intravenous administration.[38] After nighttime administration of midazolam, residual 'hangover' effects, such as sleepiness and impaired psychomotor and cognitive functions, may persist into the next day. This may impair the ability of users to drive safely and may increase the risk of falls and hip fractures.[39] Sedation, respiratory depression and hypotension due to a reduction in systematic vascular resistance, and an increase in heart rate can occur.[16][35] If intravenous midazolam is given too quickly, hypotension may occur. A "midazolam infusion syndrome" may result from high doses, is characterised by delayed arousal hours to days after discontinuation of midazolam, and may lead to an increase in the length of ventilatory support needed.[40]

In rare susceptible individuals, midazolam has been known to cause a paradoxical reaction, a well-documented complication with benzodiazepines. When this occurs, the individual may experience anxiety, involuntary movements, aggressive or violent behavior, uncontrollable crying or verbalization, and other similar effects. This seems to be related to the altered state of consciousness or disinhibition produced by the drug. Paradoxical behavior is often not recalled by the patient due to the amnesia-producing properties of the drug. In extreme situations, flumazenil can be administered to inhibit or reverse the effects of midazolam. Antipsychotic medications, such as haloperidol, have also been used for this purpose.[41]

Midazolam is known to cause respiratory depression. In healthy humans, 0.15 mg/kg of midazolam may cause respiratory depression, which is postulated to be a central nervous system (CNS) effect.[42] When midazolam is administered in combination with fentanyl, the incidence of hypoxemia or apnea becomes more likely.[43]

Although the incidence of respiratory depression/arrest is low (0.1–0.5%) when midazolam is administered alone at normal doses,[44][45] the concomitant use with CNS acting drugs, mainly analgesic opiates, may increase the possibility of hypotension, respiratory depression, respiratory arrest, and death, even at therapeutic doses.[43][44][46][47] Potential drug interactions involving at least one CNS depressant were observed for 84% of midazolam users who were subsequently required to receive the benzodiazepine antagonist flumazenil.[48] Therefore, efforts directed toward monitoring drug interactions and preventing injuries from midazolam administration are expected to have a substantial impact on the safe use of this drug.[48]

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Midazolam, when taken during the third trimester of pregnancy, may cause risk to the neonate, including benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome, with possible symptoms including hypotonia, apnoeic spells, cyanosis, and impaired metabolic responses to cold stress. Symptoms of hypotonia and the neonatal benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome have been reported to persist from hours to months after birth.[49] Other neonatal withdrawal symptoms include hyperexcitability, tremor, and gastrointestinal upset (diarrhea or vomiting). Breastfeeding by mothers using midazolam is not recommended.[50]

Elderly

Additional caution is required in the elderly, as they are more sensitive to the pharmacological effects of benzodiazepines, metabolise them more slowly, and are more prone to adverse effects, including drowsiness, amnesia (especially anterograde amnesia), ataxia, hangover effects, confusion, and falls.[9]

Tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal

A benzodiazepine dependence occurs in about one-third of individuals who are treated with benzodiazepines for longer than 4 weeks,[9] which typically results in tolerance and benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome when the dose is reduced too rapidly. Midazolam infusions may induce tolerance and a withdrawal syndrome in a matter of days. The risk factors for dependence include dependent personality, use of a benzodiazepine that is short-acting, high potency and long-term use of benzodiazepines. Withdrawal symptoms from midazolam can range from insomnia and anxiety to seizures and psychosis. Withdrawal symptoms can sometimes resemble a person's underlying condition. Gradual reduction of midazolam after regular use can minimise withdrawal and rebound effects. Tolerance and the resultant withdrawal syndrome may be due to receptor down-regulation and GABAA receptor alterations in gene expression, which causes long-term changes in the function of the GABAergic neuronal system.[9][51][52]

Chronic users of benzodiazepine medication who are given midazolam experience reduced therapeutic effects of midazolam, due to tolerance to benzodiazepines.[40][53] Prolonged infusions with midazolam results in the development of tolerance; if midazolam is given for a few days or more a withdrawal syndrome can occur. Therefore, preventing a withdrawal syndrome requires that a prolonged infusion be gradually withdrawn, and sometimes, continued tapering of dose with an oral long-acting benzodiazepine such as clorazepate dipotassium. When signs of tolerance to midazolam occur during intensive care unit sedation the addition of an opioid or propofol is recommended. Withdrawal symptoms can include irritability, abnormal reflexes, tremors, clonus, hypertonicity, delirium and seizures, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, tachycardia, hypertension, and tachypnea.[40] In those with significant dependence, sudden discontinuation may result in withdrawal symptoms such as status epilepticus.

Overdose

A midazolam overdose is considered a medical emergency and generally requires the immediate attention of medical personnel. Benzodiazepine overdose in healthy individuals is rarely life-threatening with proper medical support; however, the toxicity of benzodiazepines increases when they are combined with other CNS depressants such as alcohol, opioids, or tricyclic antidepressants. The toxicity of benzodiazepine overdose and the risk of death are also increased in the elderly and those with obstructive pulmonary disease or when used intravenously. Treatment is supportive; activated charcoal can be used within an hour of the overdose. The antidote for an overdose of midazolam (or any other benzodiazepine) is flumazenil.[35] While effective in reversing the effects of benzodiazepines it is not used in most cases as it may trigger seizures in mixed overdoses and benzodiazepine dependent individuals.[54][55]

Symptoms of midazolam overdose can include:[54][55]

|

|

Detection in body fluids

Concentrations of midazolam or its major metabolite, 1-hydroxymidazolam glucuronide, may be measured in plasma, serum, or whole blood to monitor for safety in those receiving the drug therapeutically, to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients, or to assist in a forensic investigation of a case of fatal overdosage. Patients with renal dysfunction may exhibit prolongation of elimination half-life for both the parent drug and its active metabolite, with accumulation of these two substances in the bloodstream and the appearance of adverse depressant effects.[56]

Interactions

Protease inhibitors, nefazodone, sertraline, grapefruit, fluoxetine, erythromycin, diltiazem, clarithromycin inhibit the metabolism of midazolam, leading to a prolonged action. St John's wort, rifapentine, rifampin, rifabutin, phenytoin enhance the metabolism of midazolam leading to a reduced action. Sedating antidepressants, antiepileptic drugs such as phenobarbital, phenytoin and carbamazepine, sedative antihistamines, opioids, antipsychotics and alcohol enhance the sedative effects of midazolam.[9] Midazolam is metabolized almost completely by cytochrome P450-3A4. Atorvastatin administration along with midazolam results in a reduced elimination rate of midazolam.[57] St John's wort decreases the blood levels of midazolam.[58] Grapefruit juice reduces intestinal 3A4 and results in less metabolism and higher plasma concentrations.[59]

Pharmacology

Midazolam is a short-acting benzodiazepine in adults with an elimination half-life of 1.5–2.5 hours.[7] In the elderly, as well as young children and adolescents, the elimination half-life is longer.[38][60] Midazolam is metabolised into an active metabolite alpha1-hydroxymidazolam. Age-related deficits, renal and liver status affect the pharmacokinetic factors of midazolam as well as its active metabolite.[61] However, the active metabolite of midazolam is minor and contributes to only 10 percent of biological activity of midazolam. Midazolam is poorly absorbed orally, with only 50 percent of the drug reaching the bloodstream.[9] Midazolam is metabolised by cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes and by glucuronide conjugation. Oxidation of midazolam is the major metabolite in human liver microsome (HLM).[62] The half life (T1/2) of midazolam in HLM is 3.3 min.[62] The therapeutic as well as adverse effects of midazolam are due to its effects on the GABAA receptors; midazolam does not activate GABAA receptors directly but, as with other benzodiazepines, it enhances the effect of the neurotransmitter GABA on the GABAA receptors (↑ frequency of Cl− channel opening) resulting in neural inhibition. Almost all of the properties can be explained by the actions of benzodiazepines on GABAA receptors. This results in the following pharmacological properties being produced: sedation, induction of sleep, reduction in anxiety, anterograde amnesia, muscle relaxation and anticonvulsant effects.[35]

History

Midazolam is among about 35 benzodiazepines currently used medically,[63] and was synthesized in 1975 by Walser and Fryer at Hoffmann-LaRoche, Inc in the United States.[64] Owing to its water solubility, it was found to be less likely to cause thrombophlebitis than similar drugs.[65][66] The anticonvulsant properties of midazolam were studied in the late 1970s, but not until the 1990s did it emerge as an effective treatment for convulsive status epilepticus.[67] (As of 2010), it is the most commonly used benzodiazepine in anesthetic medicine.[68] In acute medicine, midazolam has become more popular than other benzodiazepines, such as lorazepam and diazepam, because it is shorter lasting, is more potent, and causes less pain at the injection site.[63] Midazolam is also becoming increasingly popular in veterinary medicine due to its water solubility.[69] In 2018 it was revealed the CIA considered using Midazolam as a "truth serum" on terrorist suspects in project "Medication".[70]

Society and culture

Cost

Midazolam is available as a generic medication.[10]

Availability

Midazolam is available in the United States as a syrup or as an injectable solution.[71]

Dormicum brand midazolam is marketed by Roche as white, oval, 7.5-mg tablets in boxes of two or three blister strips of 10 tablets, and as blue, oval, 15-mg tablets in boxes of two (Dormonid 3x) blister strips of 10 tablets. The tablets are imprinted with "Roche" on one side and the dose of the tablet on the other side. Dormicum is also available as 1-, 3-, and 10-ml ampoules at a concentration of 5 mg/ml. Another manufacturer, Novell Pharmaceutical Laboratories, makes it available as Miloz in 3- and 5-ml ampoules. Midazolam is the only water-soluble benzodiazepine available. Another maker is Roxane Laboratories; the product in an oral solution, Midazolam HCl Syrup, 2 mg/ml clear, in a red to purplish-red syrup, cherry in flavor. It becomes soluble when the injectable solution is buffered to a pH of 2.9–3.7. Midazolam is also available in liquid form.[9] It can be administered intramuscularly,[16] intravenously,[72] intrathecally,[73] intranasally,[19] buccally,[74] or orally.[9]

Legal status

In the Netherlands, midazolam is a List II drug of the Opium Law. Midazolam is a Schedule IV drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[75] In the United Kingdom, midazolam is a Schedule 3/Class C controlled drug.[76] In the United States, midazolam (DEA number 2884) is on the Schedule IV list of the Controlled Substances Act as a non-narcotic agent with low potential for abuse.[77]

Marketing authorization

In 2011, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) granted a marketing authorisation for a buccal application form of midazolam, sold under the brand name Buccolam. Buccolam was initially approved for the treatment of prolonged, acute, convulsive seizures in people from three months to less than 18 years of age. This was the first application of a paediatric-use marketing authorisation.[78][79]

Use in executions

The drug has been introduced for use in executions by lethal injection in certain jurisdictions in the United States in combination with other drugs. It was introduced to replace pentobarbital after the latter's manufacturer disallowed that drug's use for executions.[80] Midazolam acts as a sedative but will fail to render the condemned prisoner unconscious, at which time vecuronium bromide and potassium chloride are administered, stopping the prisoner's breathing and heart, respectively. Since the condemned prisoner is not rendered unconscious but is merely sedated, the administration of vecuronium bromide and potassium chloride can cause extreme pain and panic in the person being executed.[81]

Midazolam has been used as part of a three-drug cocktail, with vecuronium bromide and potassium chloride, in Florida and Oklahoma prisons.[82] Midazolam has also been used along with hydromorphone in a two-drug protocol in Ohio and Arizona.[82]

Notable incidents

The state of Florida used midazolam to execute William Frederick Happ in October 2013.[81]

The state of Ohio used midazolam in the execution of Dennis McGuire in January 2014; it took McGuire 24 minutes to die after the procedure started, and he gasped and appeared to be choking during that time, leading to questions about the dosing and timing of the drug administration, as well as the choice of drugs.[83]

The usage of midazolam in executions became controversial after condemned inmate Clayton Lockett apparently regained consciousness and started speaking midway through his 2014 execution when the state of Oklahoma attempted to execute him with an untested three-drug lethal injection combination using 100 mg of midazolam. Prison officials reportedly discussed taking him to a hospital before he was pronounced dead of a heart attack 40 minutes after the execution began. An observing doctor stated that Lockett's vein had ruptured. It is not clear whether his death was caused by one or more of the drugs or by a problem in the administration procedure, nor is it clear what quantities of vecuronium bromide and potassium chloride were released to his system before the execution was cancelled.[84][85]

According to news reports, the execution of Ronald Bert Smith in the state of Alabama on 8 December 2016 went awry[clarification needed] soon after midazolam was administered,[86] again putting the effectiveness of the drug in question.[80]

In October 2016, the state of Ohio announced that it would resume executions in January 2017, using a formulation of midazolam, vecuronium bromide, and potassium chloride, but this was blocked by a federal judge.[87][88] On 26 July 2017, Ronald Phillips was executed with a three-drug cocktail including midazolam after the Supreme Court refused to grant a stay.[89] Prior to this, the last execution in Ohio had been that of Dennis McGuire.[90] Murderer Gary Otte's lawyers unsuccessfully challenged his Ohio execution, arguing that midazolam might not protect him from serious pain when the other drugs are administered. He died without incident in about 14 minutes on 13 September 2017.[91]

On 24 April 2017, the state of Arkansas carried out a double-execution, of Jack Harold Jones, 52, and Marcel Williams, 46. Arkansas attempted to execute eight people before its supply of midazolam expired on 30 April 2017. Two of them were granted a stay of execution, and another, Ledell T. Lee, 51, was executed on 20 April 2017.[92]

On 28 October 2021, the state of Oklahoma executed inmate John Marion Grant, 60, using midazolam as part of its three-drug cocktail hours after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled to lift a stay of execution for Oklahoma death row inmates. The execution was the state's first since 2015. Witnesses to the execution said that when the first drug, midazolam, began to flow at 4:09 p.m., Grant started convulsing about two dozen times and vomited. Grant continued breathing, and a member of the execution team wiped the vomit off his face. At 4:15 p.m., officials said Grant was unconscious, and he was pronounced dead at 4:21 p.m.[93]

Legal challenges

In Glossip v. Gross, attorneys for three Oklahoma inmates argued that midazolam could not achieve the level of unconsciousness required for surgery, meaning severe pain and suffering was likely. They argued that midazolam was cruel and unusual punishment and thus contrary to the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution. In June 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that they had failed to prove that midazolam was cruel and unusual when compared to known, available alternatives.[94]

The state of Nevada is also known to use midazolam in execution procedures. In July 2018, one of the manufacturers accused state officials of obtaining the medication under pretences. This incident was the first time a drug company successfully, though temporarily, halted an execution.[95] A previous attempt in 2017, to halt an execution in the state of Arizona by another drug manufacturer was not successful.[96]

References

- ↑ "Buccolam 10 mg oromucosal solution - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". 7 June 2022. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/7460/smpc.

- ↑ "Hypnovel 10mg in 2ml - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". 16 February 2022. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/10948/smpc.

- ↑ "Seizalam- midazolam hydrochloride injection, solution". https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=cb2381bf-984a-48a8-95c0-3017c34cc170.

- ↑ "Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of midazolam in man". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 16 (Suppl 1): 43S–49S. 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1983.tb02270.x. PMID 6138080.

- ↑ "Contribution of midazolam and its 1-hydroxy metabolite to preoperative sedation in children: a pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic analysis". British Journal of Anaesthesia 89 (3): 428–437. September 2002. doi:10.1093/bja/aef213. PMID 12402721.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 "Midazolam Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. https://www.drugs.com/monograph/midazolam-hydrochloride.html.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Midazolam Injection". New Zealand Ministry of Health. 26 October 2012. http://www.medsafe.govt.nz/profs/datasheet/m/MidazolaminjPfizer.pdf.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Nonintravenous midazolam versus intravenous or rectal diazepam for the treatment of early status epilepticus: A systematic review with meta-analysis". Epilepsy & Behavior 49: 325–336. August 2015. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.02.030. PMID 25817929.

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 "Benzodiazepines in epilepsy: pharmacology and pharmacokinetics". Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 118 (2): 69–86. August 2008. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01004.x. PMID 18384456.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. 2015. p. 21. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ↑ "Midazolam use while Breastfeeding". https://www.drugs.com/breastfeeding/midazolam.html.

- ↑ Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. 2006. p. 539. ISBN 9783527607495. https://books.google.com/books?id=FjKfqkaKkAAC&pg=PA539. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ↑ World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2021. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ↑ "Benzodiazepines in the treatment of epilepsy in people with intellectual disability". Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 42 (Suppl 1): 80–92. December 1998. PMID 10030438.

- ↑ "Drug management for acute tonic-clonic convulsions including convulsive status epilepticus in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1 (1): CD001905. January 2018. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001905.pub3. PMID 29320603.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 "Status epilepticus: an evidence based guide". BMJ 331 (7518): 673–677. September 2005. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7518.673. PMID 16179702.

- ↑ "Refractory status epilepticus". Neurology India 54 (4): 354–358. December 2006. doi:10.4103/0028-3886.28104. PMID 17114841.

- ↑ "Pharmacologic management of convulsive status epilepticus in childhood". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics 5 (6): 777–783. November 2005. doi:10.1586/14737175.5.6.777. PMID 16274335.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Intranasal midazolam therapy for pediatric status epilepticus". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 24 (3): 343–346. May 2006. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2005.11.004. PMID 16635708.

- ↑ "Management of prolonged seizures and status epilepticus in childhood: a systematic review". Journal of Child Neurology 24 (8): 918–926. August 2009. doi:10.1177/0883073809332768. PMID 19332572.

- ↑ "Procedural sedation in the acute care setting". American Family Physician 71 (1): 85–90. January 2005. PMID 15663030.

- ↑ "Sedation management in Australian and New Zealand intensive care units: doctors' and nurses' practices and opinions". American Journal of Critical Care 19 (3): 285–295. May 2010. doi:10.4037/ajcc2009541. PMID 19770414.

- ↑ "A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials of moderate sedation for routine endoscopic procedures". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 67 (6): 910–923. May 2008. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2007.12.046. PMID 18440381.

- ↑ "Sedation in PACU: the role of benzodiazepines". Current Drug Targets 6 (7): 745–748. November 2005. doi:10.2174/138945005774574416. PMID 16305452.

- ↑ "Sedation in PACU: the role of propofol". Current Drug Targets 6 (7): 741–744. November 2005. doi:10.2174/138945005774574425. PMID 16305451.

- ↑ "[Recommendations for analgesia and sedation in neonatal intensive care]". Medycyna Wieku Rozwojowego 12 (4 Pt 1): 958–967. Oct–Dec 2008. PMID 19471072.

- ↑ "Opioids for neonates receiving mechanical ventilation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2021 (1): CD004212. January 2008. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004212.pub3. PMID 18254040.

- ↑ "Sedation of children undergoing dental treatment". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018 (12): CD003877. December 2018. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003877.pub5. PMID 30566228.

- ↑ "Haloperidol plus promethazine for psychosis-induced aggression". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016 (11): CD005146. November 2016. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005146.pub3. PMID 27885664.

- ↑ Liverpool Care Pathway (January 2005). "Care of the Dying Pathway (lcp) (Hospital)". United Kingdom. http://www.mcpcil.org.uk/liverpool-care-pathway/pdfs/LCP%20HOSPITAL%20VERSION%2011%20%28printable%20version%29.pdf.

- ↑ "Palliative sedation therapy in the last weeks of life: a literature review and recommendations for standards". Journal of Palliative Medicine 10 (1): 67–85. February 2007. doi:10.1089/jpm.2006.0139. PMID 17298256.

- ↑ Royal College of Physicians (September 2009). "National care of the dying audit 2009". United Kingdom. http://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/media/press-releases/Pages/National-care-of-the-dying-audit-2009.aspx. "[I]n their last 24 hours... 31% had low doses of medication to [control distress from agitation or restlessness]... the remaining 4% required higher doses"

- ↑ "Benzodiazepine dependence: focus on withdrawal syndrome". Annales Pharmaceutiques Françaises 67 (6): 408–413. November 2009. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2009.07.001. PMID 19900604.

- ↑ "Economic evaluation of propofol and lorazepam for critically ill patients undergoing mechanical ventilation". Critical Care Medicine 36 (3): 706–714. March 2008. doi:10.1097/CCM.0B013E3181544248. PMID 18176312.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 "Midazolam and other benzodiazepines". Modern Anesthetics. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 182. 2008. pp. 335–360. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-74806-9_16. ISBN 978-3-540-72813-9.

- ↑ "Pharmacokinetics and dosage adjustment in patients with hepatic dysfunction". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 64 (12): 1147–1161. December 2008. doi:10.1007/s00228-008-0553-z. PMID 18762933.

- ↑ "Metamemory without the memory: are people aware of midazolam-induced amnesia?". Psychopharmacology 177 (3): 336–343. January 2005. doi:10.1007/s00213-004-1958-8. PMID 15290003.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "The place of premedication in pediatric practice". Pediatric Anesthesia 19 (9): 817–828. September 2009. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9592.2009.03114.x. PMID 19691689.

- ↑ "Residual effects of hypnotics: epidemiology and clinical implications". CNS Drugs 18 (5): 297–328. 2004. doi:10.2165/00023210-200418050-00003. PMID 15089115.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 "Analgesia and sedation in children: practical approach for the most frequent situations". Jornal de Pediatria 83 (2 Suppl): S71–S82. May 2007. doi:10.2223/JPED.1625. PMID 17530139. http://www.jped.com.br/conteudo/07-83-S71/ing.asp?cod=1625.

- ↑ "Paradoxical reactions to benzodiazepines: literature review and treatment options". Pharmacotherapy 24 (9): 1177–1185. September 2004. doi:10.1592/phco.24.13.1177.38089. PMID 15460178. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/489358_6.

- ↑ "Midazolam: pharmacology and uses". Anesthesiology 62 (3): 310–324. March 1985. doi:10.1097/00000542-198503000-00017. PMID 3156545.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 "Frequent hypoxemia and apnea after sedation with midazolam and fentanyl". Anesthesiology 73 (5): 826–830. November 1990. doi:10.1097/00000542-199011000-00005. PMID 2122773.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 "Intensive surveillance of midazolam use in hospitalized patients and the occurrence of cardiorespiratory arrest". Pharmacotherapy 12 (3): 213–216. 1992. doi:10.1002/j.1875-9114.1992.tb04512.x. PMID 1608855.

- ↑ "Midazolam use in the emergency department". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 8 (2): 97–100. March 1990. doi:10.1016/0735-6757(90)90192-3. PMID 2302291.

- ↑ "Midazolam-fentanyl intravenous sedation in children: case report of respiratory arrest". Pediatrics 86 (3): 463–467. September 1990. doi:10.1542/peds.86.3.463. PMID 2388795.

- ↑ "Sudden hypotension associated with midazolam and sufentanil". Anesthesia and Analgesia 66 (7): 693–694. July 1987. doi:10.1213/00000539-198707000-00026. PMID 2955719.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 "Midazolam-related drug interactions: detection of risk situations to the patient safety in a brazilian teaching hospital". Journal of Patient Safety 5 (2): 69–74. June 2009. doi:10.1097/PTS.0b013e3181a5dafa. PMID 19920444.

- ↑ "The effects of benzodiazepine use during pregnancy and lactation". Reproductive Toxicology 8 (6): 461–475. Nov–Dec 1994. doi:10.1016/0890-6238(94)90029-9. PMID 7881198.

- ↑ "[Drugs during preeclampsia. Fetal risks and pharmacology]". Annales Françaises d'Anesthésie et de Réanimation 29 (4): e37–e46. April 2010. doi:10.1016/j.annfar.2010.02.016. PMID 20347563.

- ↑ "Midazolam induces expression of c-Fos and EGR-1 by a non-GABAergic mechanism". Anesthesia and Analgesia 95 (2): 373–8, table of contents. August 2002. doi:10.1097/00000539-200208000-00024. PMID 12145054.

- ↑ "Minimizing tolerance and withdrawal to prolonged pediatric sedation: case report and review of the literature". Journal of Intensive Care Medicine 22 (3): 173–179. 2007. doi:10.1177/0885066607299556. PMID 17569173.

- ↑ "Assessment of GABA(A)benzodiazepine receptor (GBzR) sensitivity in patients on benzodiazepines". Psychopharmacology 146 (2): 180–184. September 1999. doi:10.1007/s002130051104. PMID 10525753. http://link.springer.de/link/service/journals/00213/bibs/9146002/91460180.htm.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Davidson's principles practice of medicine. Edinburgh: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. 2006. pp. 212–213. ISBN 978-0-443-10057-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=TI8DHMKDF-4C&pg=PA212.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Addiction medicine: an evidence-based handbook. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams Wilkins. 2005. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-7817-6154-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=DKUQ5YrFZd8C&pg=PA80.

- ↑ Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City CA: Biomedical Publications. 2008. pp. 1037–40. ISBN 978-0-9626523-7-0.

- ↑ "The effects of concurrent atorvastatin therapy on the pharmacokinetics of intravenous midazolam". Anaesthesia 58 (9): 899–904. September 2003. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2044.2003.03339.x. PMID 12911366.

- ↑ "Herb-drug interactions: a literature review". Drugs 65 (9): 1239–1282. 2005. doi:10.2165/00003495-200565090-00005. PMID 15916450.

- ↑ "Grape fruit juice-drug interactions". Pakistan Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 18 (4): 45–57. October 2005. PMID 16380358.

- ↑ Clinical Anesthesia (6th ed.). Lippincott Williams Wilkins. 1 April 2009. p. 588. ISBN 978-0-7817-8763-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=-YI9P2DLe9UC&pg=PA588.

- ↑ "Clinical pharmacokinetic monitoring of midazolam in critically ill patients". Pharmacotherapy 27 (3): 389–398. March 2007. doi:10.1592/phco.27.3.389. PMID 17316150.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 "High-Throughput Metabolic Soft-Spot Identification in Liver Microsomes by LC/UV/MS: Application of a Single Variable Incubation Time Approach". Molecules 27 (22): 8058. November 2022. doi:10.3390/molecules27228058. PMID 36432161.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Short Textbook of Pharmacology for Dental and Allied Health Sciences. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers. 30 May 2008. p. 128. ISBN 978-81-8448-149-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=L1DgbIE0V9sC.

- ↑ Walser A, Fryer RI, Benjamin L, "Imidazo[1,5-α] [1,4]benzodiazepines", US patent 4166185, published 1979-08-28, issued 1979-08-28, assigned to Hoffmann La Roche Inc.

- ↑ Cardiac Anesthesia (5th ed.). W.B. Saunders Company. 15 May 2006. ISBN 978-1-4160-0253-6.

- ↑ Sedation: a guide to patient management. St. Louis: Mosby. 16 October 2002. p. 335. ISBN 978-0-323-01226-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=StZpAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ Pediatric critical care medicine: basic science and clinical evidence. London: Springer. 2007. p. 984. ISBN 978-1-84628-463-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=ml5bx1PxxOQC.

- ↑ Hypertension: a companion to Brenner and Rector's the kidney (2 ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby. 22 April 2005. p. 816. ISBN 978-0-7216-0258-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=6YUJXURDEZkC.

- ↑ Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. Wiley-Blackwell. 30 March 2009. p. 358. ISBN 978-0-8138-2061-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=ievLulSqwBAC.

- ↑ "CIA considered potential truth serum for terror suspects after 9/11". 13 November 2018. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/cia-considered-potential-truth-serum-terror-suspects-after-9-11-n935911.

- ↑ FDA, ed (2015). "Orange Book: Approved Drug Products; Midazolam". http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/ob/docs/tempai.cfm#.VbN3x2MS.

- ↑ "[Anaesthetic considerations for interventional radiology]". Annales Françaises d'Anesthésie et de Réanimation 25 (6): 615–625. June 2006. doi:10.1016/j.annfar.2006.01.018. PMID 16632296.

- ↑ "Use of intrathecal midazolam to improve perioperative analgesia: a meta-analysis". Anaesthesia and Intensive Care 36 (3): 365–373. May 2008. doi:10.1177/0310057X0803600307. PMID 18564797.

- ↑ "An alternative perspective on the management of status epilepticus". Epilepsy & Behavior 12 (3): 349–353. April 2008. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.12.013. PMID 18262847.

- ↑ International Narcotics Control Board (August 2003). "List of psychotropic substances under international control". incb.org. http://www.incb.org/pdf/e/list/green.pdf.

- ↑ Blackpool NHS Primary Care Trust (2007). "Medicines Management Update". United Kingdom: National Health Service. http://www.blackpool.nhs.uk/images/uploads/CD-update-GP-v2-may08.pdf.

- ↑ "US DEA Schedules". http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/schedules/.

- ↑ "Monthly Report". Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). 5 July 2011. p. 1. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Committee_meeting_report/2011/07/WC500108232.pdf.

- ↑ "ViroPharma's Buccolam (Midazolam, Oromucosal Solution) Granted European Marketing Authorization for Treatment of Acute Seizures". PR Newswire. 6 September 2011. http://www.wallstreet-online.de/nachricht/3364595-viropharma-s-buccolam-midazolam-oromucosal-solution-granted-european-marketing-authorization-for-treatment-of-acute-seizures.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 "Die fahrlässige Hinrichtung des Ronald Smith" (in de). der Spiegel. 10 December 2016. http://www.spiegel.de/panorama/justiz/todesstrafe-qualvolle-hinrichtung-loest-streit-ueber-todesstrafe-aus-a-1125340.html.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 "Happ executed using new drug". The Gainesville Sun. 15 October 2013. http://www.gainesville.com/article/20131015/ARTICLES/131019753.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 "State by State Lethal Injection". Death Penalty Information Center. http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/state-lethal-injection.

- ↑ "Controversial execution in Ohio uses new drug combination". CNN. 16 January 2014. http://www.cnn.com/2014/01/16/justice/ohio-dennis-mcguire-execution/.

- ↑ "One execution botched, Oklahoma delays the next". 29 April 2014. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/30/us/oklahoma-executions.html.

- ↑ "Oklahoma execution: Clayton Lockett writhes on gurney in botched procedure". The Guardian (London). 30 April 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/apr/30/oklahoma-execution-botched-clayton-lockett.

- ↑ "The Drug Used in Alabama's Problematic Execution Has a Controversial History". Time (magazine). 9 December 2016. http://time.com/4596573/alabama-execution-ronald-bert-smith-midazolam/. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ↑ "Federal Judge Blocks Ohio's Lethal Injection Protocol". NPR. 26 January 2017. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/01/26/511792736/federal-judge-blocks-ohios-lethal-injection-protocol.

- ↑ "When a Common Sedative Becomes an Execution Drug". The New York Times. 13 March 2017. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/13/us/midazolam-death-penalty-arkansas.html.

- ↑ "Ohio puts killer of 3 year-old to death in first execution in more than three years". New York. 25 July 2017. http://www.nydailynews.com/news/national/state-ohio-executes-killer-3-year-old-girl-article-1.3358523.

- ↑ "Ohio to resume executions with new jab". BBC News. 3 October 2016. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-37545854.

- ↑ "Ohio executes man convicted of killing two in back-to-back robberies". Associated Press. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/ohio-executes-man-convicted-of-killing-two-in-back-to-back-robberies/.

- ↑ "Arkansas Executes Ledell Lee, State's First Inmate Put to Death Since 2005". NBC News. 21 April 2017. http://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/lethal-injection/arkansas-executes-ledell-lee-states-first-inmate-put-death-2005-n749156/.

- ↑ KOCO Staff (28 October 2021). "Oklahoma executes death row inmate John Grant". ABC News. http://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/lethal-injection/arkansas-executes-ledell-lee-states-first-inmate-put-death-2005-n749156/.

- ↑ "US Supreme Court backs use of contentious execution drug". BBC News. 29 June 2015. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-33314067.

- ↑ "Death row prisoner kills himself after execution halted". Newsweek. 6 January 2019. https://www.newsweek.com/scott-dozier-death-row-prisoner-kills-himself-after-execution-halted-1280675?amp=1.

- ↑ "Nevada inmate on death row whose execution was delayed commits suicide". 5 January 2019. https://thehill.com/blogs/blog-briefing-room/news/424035-nevada-inmate-on-death-row-whose-execution-was-delayed-commits.

External links

- "Midazolam". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://druginfo.nlm.nih.gov/drugportal/name/midazolam.

- "Midazolam hydrochloride". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://druginfo.nlm.nih.gov/drugportal/name/midazolam%20hydrochloride.

- Inchem - Midazolam

|