Chemistry:Propylene

Propylene, also known as propene, is an unsaturated organic compound with the chemical formula CH

3CH=CH

2. It has one double bond, and is the second simplest member of the alkene class of hydrocarbons. It is a colorless gas with a faint petroleum-like odor.[1]

Propylene is a product of combustion from forest fires, cigarette smoke, and motor vehicle and aircraft exhaust.[2] It was discovered in 1850 by A. W. von Hoffmann's student Captain (later Major General[3]) John Williams Reynolds as the only gaseous product of thermal decomposition of amyl alcohol to react with chlorine and bromine.[4]

Production

Steam cracking

The dominant technology for producing propylene is steam cracking, using propane as the feedstock. Cracking propane yields a mixture of ethylene, propylene, methane, hydrogen gas, and other related compounds. The yield of propylene is about 15%. The other principal feedstock is naphtha, especially in the Middle East and Asia.[5] Propylene can be separated by fractional distillation from the hydrocarbon mixtures obtained from cracking and other refining processes; refinery-grade propene is about 50 to 70%.[6] In the United States, shale gas is a major source of propane.

Olefin conversion technology

In the Phillips triolefin or olefin conversion technology, propylene is interconverted with ethylene and 2-butenes. Rhenium and molybdenum catalysts are used:[7]

The technology is founded on an olefin metathesis reaction discovered at Phillips Petroleum Company.[8][9] Propylene yields of about 90 wt% are achieved.

Related is the Methanol-to-Olefins/Methanol-to-Propene process. It converts synthesis gas (syngas) to methanol, and then converts the methanol to ethylene and/or propene. The process produces water as a by-product. Synthesis gas is produced from the reformation of natural gas or by the steam-induced reformation of petroleum products such as naphtha, or by gasification of coal or natural gas.

Fluid catalytic cracking

High severity fluid catalytic cracking (FCC) uses traditional FCC technology under severe conditions (higher catalyst-to-oil ratios, higher steam injection rates, higher temperatures, etc.) in order to maximize the amount of propene and other light products. A high severity FCC unit is usually fed with gas oils (paraffins) and residues, and produces about 20–25% (by mass) of propene on feedstock together with greater volumes of motor gasoline and distillate byproducts. These high temperature processes are expensive and have a high carbon footprint. For these reasons, alternative routes to propylene continue to attract attention.[10]

Other commercialized methods

On-purpose propylene production technologies were developed throughout the twentieth century. Of these, propane dehydrogenation technologies such as the CATOFIN and OLEFLEX processes have become common, although they still make up a minority of the market, with most of the olefin being sourced from the above mentioned cracking technologies. Platinum, chromia, and vanadium catalysts are common in propane dehydrogenation processes.

Market

Propene production has remained static at around 35 million tonnes (Europe and North America only) from 2000 to 2008, but it has been increasing in East Asia, most notably Singapore and China.[11] Total world production of propene is currently about half that of ethylene.

Research

The use of engineered enzymes has been explored but has not been commercialized.[12]

There is ongoing research into the use of oxygen carrier catalysts for the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane. This poses several advantages, as this reaction mechanism can occur at lower temperatures than conventional dehydrogenation, and may not be equilibrium-limited because oxygen is used to combust the hydrogen by-product.[13]

Uses

Propylene is the second most important starting product in the petrochemical industry after ethylene. It is the raw material for a wide variety of products. Polypropylene manufacturers consume nearly two thirds of global production.[14] Polypropylene end uses include films, fibers, containers, packaging, and caps and closures. Propene is also used for the production of chemicals such as propylene oxide, acrylonitrile, cumene, butyraldehyde, and acrylic acid. In the year 2013 about 85 million tonnes of propylene were processed worldwide.[14]

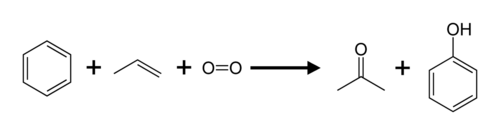

Propylene and benzene are converted to acetone and phenol via the cumene process.

Propylene is also used to produce isopropyl alcohol (propan-2-ol), acrylonitrile, propylene oxide, and epichlorohydrin.[15] The industrial production of acrylic acid involves the catalytic partial oxidation of propylene.[16] Propylene is an intermediate in the oxidation to acrylic acid.

In industry and workshops, propylene is used as an alternative fuel to acetylene in Oxy-fuel welding and cutting, brazing and heating of metal for the purpose of bending. It has become a standard in BernzOmatic products and others in MAPP substitutes,[17] now that true MAPP gas is no longer available.

Reactions

Propylene resembles other alkenes in that it undergoes electrophilic addition reactions relatively easily at room temperature. The relative weakness of its double bond explains its tendency to react with substances that can achieve this transformation. Alkene reactions include:

- Polymerization and oligomerization

- Oxidation

- Halogenation

- Hydrohalogenation

- Alkylation

- Hydration

- Hydroformylation

Complexes of transition metals

Foundational to hydroformylation, alkene metathesis, and polymerization are metal-propylene complexes, which are intermediates in these processes. Propylene is prochiral, meaning that binding of a reagent (such as a metal electrophile) to the C=C group yields one of two enantiomers.

Polymerization

The majority of propylene is used to form polypropylene, a very important commodity thermoplastic, through chain-growth polymerization.[14] In the presence of a suitable catalyst (typically a Ziegler–Natta catalyst), propylene will polymerize. There are multiple ways to achieve this, such as using high pressures to suspending the catalyst in a solution of liquid propylene, or running gaseous propylene through a fluidized bed reactor.[18]

593x593px

Oligomerization

In the presence of catalysts, propylene will form various short oligomers. It can dimerizes to give 2,3-dimethyl-1-butene and/or 2,3-dimethyl-2-butene.[19] or trimerise to form tripropylene.

Environmental safety

Propene is a product of combustion from forest fires, cigarette smoke, and motor vehicle and aircraft exhaust.[2] It is an impurity in some heating gases. Observed concentrations have been in the range of 0.1–4.8 parts per billion (ppb) in rural air, 4–10.5 ppb in urban air, and 7–260 ppb in industrial air samples.[6]

In the United States and some European countries a threshold limit value of 500 parts per million (ppm) was established for occupational (8-hour time-weighted average) exposure. It is considered a volatile organic compound (VOC) and emissions are regulated by many governments, but it is not listed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as a hazardous air pollutant under the Clean Air Act. With a relatively short half-life, it is not expected to bioaccumulate.[6]

Propene has low acute toxicity from inhalation and is not considered to be carcinogenic. Chronic toxicity studies in mice did not yield significant evidence suggesting adverse effects. Humans briefly exposed to 4,000 ppm did not experience any noticeable effects.[20] Propene is dangerous from its potential to displace oxygen as an asphyxiant gas, and from its high flammability/explosion risk.

Bio-propylene is the bio-based propylene.[21][22] It has been examined, motivated by diverse interests such a carbon footprint. Production from glucose has been considered.[23] More advanced ways of addressing such issues focus on electrification alternatives to steam cracking.

Storage and handling

Propene is flammable. Propene is usually stored as liquid under pressure, although it is also possible to store it safely as gas at ambient temperature in approved containers.[24]

Occurrence in nature

Propene is detected in the interstellar medium through microwave spectroscopy.[25] On September 30, 2013, NASA announced the detection of small amounts of naturally occurring propene in the atmosphere of Titan using infrared spectroscopy.[26][27][28] The detection was made by a team led by NASA GSFC scientist Conor Nixon using data from the CIRS instrument [29][30] on the Cassini orbiter spacecraft, part of the Cassini-Huygens mission. Its confirmation solved a 32-year old mystery by filling a predicted gap in Titan's detected hydrocarbons, adding the C3H6 species (propene) to the already-detected C3H4 (propyne) and C3H8 (propane).[31]

See also

- Los Alfaques disaster

- Inhalant abuse

- 2014 Kaohsiung gas explosions

- 2020 Houston explosion

- Titan (moon)

References

- ↑ "Propylene". https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Propene#section=Top.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Morgott, David (2018-01-04). "The Human Exposure Potential from Propylene Releases to the Environment" (in en). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15 (1): 66. doi:10.3390/ijerph15010066. ISSN 1660-4601. PMID 29300328.

- ↑ "Maj Gen John Williams Reynolds, FCS" (in en-US). 1816-12-25. https://www.geni.com/people/Maj-Gen-John-Reynolds-FCS/6000000184928583829.

- ↑ Rasmussen, Seth C. (2018), Rasmussen, Seth C., ed., "Introduction" (in en), Acetylene and Its Polymers: 150+ Years of History, SpringerBriefs in Molecular Science (Cham: Springer International Publishing): pp. 1–19, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-95489-9_1, ISBN 978-3-319-95489-9

- ↑ Ashford's Dictionary of Industrial Chemicals, Third edition, 2011, ISBN 978-0-9522674-3-0, pages 7766–9

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "Product Safety Assessment(PSA): Propylene". Dow Chemical Co.. http://www.dow.com/productsafety/finder/pro.htm.

- ↑ Ghashghaee, Mohammad (2018). "Heterogeneous catalysts for gas-phase conversion of ethylene to higher olefins". Rev. Chem. Eng. 34 (5): 595–655. doi:10.1515/revce-2017-0003.

- ↑ Banks, R. L.; Bailey, G. C. (1964). "Olefin Disproportionation. A New Catalytic Process". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Product Research and Development 3 (3): 170–173. doi:10.1021/i360011a002.

- ↑ Lionel Delaude; Alfred F. Noels (2005). Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/0471238961.metanoel.a01. ISBN 978-0-471-23896-6.

- ↑ Schiffer, Zachary J.; Manthiram, Karthish (2017). "Electrification and Decarbonization of the Chemical Industry". Joule 1 (1): 10–14. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2017.07.008. Bibcode: 2017Joule...1...10S.

- ↑ Amghizar, Ismaël; Vandewalle, Laurien A.; Van Geem, Kevin M.; Marin, Guy B. (2017). "New Trends in Olefin Production". Engineering 3 (2): 171–178. doi:10.1016/J.ENG.2017.02.006. Bibcode: 2017Engin...3..171A.

- ↑ de Guzman, Doris (October 12, 2012). "Global Bioenergies in bio-propylene". https://greenchemicalsblog.com/2012/10/12/global-bioenergies-in-bio-propylene.

- ↑ Wu, Tianwei et al. (2020). "Chemical looping oxidative dehydrogenation of propane: A comparative study of Ga-based, Mo-based, V-based oxygen carriers". Chemical Engineering and Processing - Process Intensification 157. doi:10.1016/j.cep.2020.108137. ISSN 0255-2701. Bibcode: 2020CEPPI.15708137W.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 "Market Study: Propylene (2nd edition), Ceresana, December 2014". ceresana.com. http://www.ceresana.com/en/market-studies/chemicals/propylene/.

- ↑ Budavari, Susan, ed (1996). "8034. Propylene". The Merck Index, Twelfth Edition. New Jersey: Merck & Co.. pp. 1348–1349.

- ↑ J.G.L., Fierro (Ed.) (2006). Metal Oxides, Chemistry and Applications. CRC Press. pp. 414–455.

- ↑ For example, "MAPP-Pro"

- ↑ Heggs, T. Geoffrey (2011-10-15), Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, ed. (in en), Polypropylene, Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, pp. o21_o04, doi:10.1002/14356007.o21_o04, ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14356007.o21_o04, retrieved 2021-07-09

- ↑ Olivier-Bourbigou, H.; Breuil, P. A. R.; Magna, L.; Michel, T.; Espada Pastor, M. Fernandez; Delcroix, D. (2020). "Nickel Catalyzed Olefin Oligomerization and Dimerization". Chemical Reviews 120 (15): 7919–7983. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00076. PMID 32786672. https://hal-ifp.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02954532/file/Nickel%20Catalyzed%20Olefin.pdf.

- ↑ PubChem. "Hazardous Substances Data Bank (HSDB): 175" (in en). https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/source/hsdb/175#section=Human-Toxicity-Excerpts-(Complete).

- ↑ Bio-based drop-in, smart drop-in and dedicated chemicals

- ↑ Duurzame bioplastics op basis van hernieuwbare grondstoffen

- ↑ Guzman, Doris de (12 October 2012). "Global Bioenergies in bio-propylene" (in en-US). https://greenchemicalsblog.com/2012/10/12/global-bioenergies-in-bio-propylene/.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, Fourth edition, 1996, ISBN 0471-52689-4 (v.20), page 261

- ↑ Marcelino, N.; Cernicharo, J.; Agúndez, M. et al. (2007-08-10). "Discovery of Interstellar Propylene (CH2CHCH3): Missing Links in Interstellar Gas-Phase Chemistry". The Astrophysical Journal (IOP) 665 (2): L127–L130. doi:10.1086/521398. Bibcode: 2007ApJ...665L.127M.

- ↑ "Spacecraft finds propylene on Saturn moon, Titan". UPI.com. 2013-09-30. http://www.upi.com/Science_News/2013/09/30/Cassini-finds-ingredient-of-household-plastic-on-Saturn-moon/UPI-42881380571911/.

- ↑ "Cassini finds ingredient of household plastic on Saturn moon". Spacedaily.com. http://www.spacedaily.com/reports/Cassini_finds_ingredient_of_household_plastic_on_Saturn_moon_999.html.

- ↑ Nixon, C. A.; Jennings, D. E.; Bézard, B.; Vinatier, S.; Teanby, N. A.; Sung, K.; Ansty, T. M.; Irwin, P. G. J. et al. (2013-09-30). "Detection of Propene in Titan's Stratosphere". The Astrophysical Journal 776 (1): L14. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/776/1/L14. ISSN 2041-8205. Bibcode: 2013ApJ...776L..14N. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/2041-8205/776/1/L14.

- ↑ Flasar, F. M.; Kunde, V. G.; Abbas, M. M.; Achterberg, R. K.; Ade, P.; Barucci, A.; Bézard, B.; Bjoraker, G. L. et al. (2004), Russell, Christopher T., ed., "Exploring the Saturn System in the Thermal Infrared: The Composite Infrared Spectrometer" (in en), The Cassini-Huygens Mission: Orbiter Remote Sensing Investigations (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands): pp. 169–297, doi:10.1007/1-4020-3874-7_4, ISBN 978-1-4020-3874-7, Bibcode: 2004chm..book..169F, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/1-4020-3874-7_4, retrieved 2025-01-05

- ↑ Jennings, D. E.; Flasar, F. M.; Kunde, V. G.; Nixon, C. A.; Segura, M. E.; Romani, P. N.; Gorius, N.; Albright, S. et al. (2017-06-20). "Composite infrared spectrometer (CIRS) on Cassini" (in EN). Applied Optics 56 (18): 5274–5294. doi:10.1364/AO.56.005274. ISSN 2155-3165. PMID 29047582. Bibcode: 2017ApOpt..56.5274J. https://opg.optica.org/ao/abstract.cfm?uri=ao-56-18-5274.

- ↑ Maguire, W. C.; Hanel, R. A.; Jennings, D. E.; Kunde, V. G.; Samuelson, R. E. (August 1981). "C3H8 and C3H4 in Titan's atmosphere" (in en). Nature 292 (5825): 683–686. doi:10.1038/292683a0. ISSN 1476-4687. https://www.nature.com/articles/292683a0.

|