Chemistry:Propylhexedrine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Benzedrex, Obesin, Dristan Inhaler, and others |

| Other names |

|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Medical: Intranasal (inhaler) and oral Recreational: Oral and parenteral routes |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | 4 ± 1.5 hours |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII |

|

| KEGG | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C10H21N |

| Molar mass | 155.285 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| |

| |

| | |

Propylhexedrine, commonly sold under the brand name Benzedrex, is an alkylamine primarily utilized as a topical nasal decongestant.[1] Its main indications are relief of congestion due to colds, allergies, and allergic rhinitis.[2]

Medical use

Propylhexedrine is used to treat acute nasal congestion related to the common cold, allergies and hay fever. For nasal congestion, the dosage is listed as four inhalations (two inhalations per nostril) every two hours for adults and children 6–12 years of age. Each inhalation delivers 0.4 to 0.5 milligrams (400 to 500 μg) in 800 millilitres of air.[2][3] Use is not to exceed three days.[2]

Historically, it has also been used for weight loss in oral tablet preparations at doses ranging from 5 to 30 milligrams.[4] No medications containing propylhexedrine are currently approved for weight loss in any country since roughly 1976.[5][6]

Contraindications

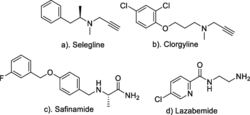

Propylhexedrine should not be used if a MAOI has been used in the past 14 days or is currently in use by a person.[7]

Unlike other topical decongestants, propylhexedrine is not required to carry a warning against use in individuals with hypertension.[8]

Propylhexedrine is contraindicated in individuals under six years old.[9] There is at least one case of reported accidental poisoning resulting from a child's access to a propylhexedrine product.[10]

Adverse effects

When used as an inhaler, the most common adverse effects warned about for propylhexedrine are temporary discomfort (e.g., stinging or burning sensations) or rebound congestion.[2] The sharing of propylhexedrine inhalers may spread infection.[2] The occurrence of these adverse effects is uncommon as propylhexedrine is generally recognized as safe and effective.[11] However, the use of propylhexedrine products in manners not intended by their labeling can result in severe adverse effects not typically encountered in therapeutic settings.[12][13][14] The outcomes of improperly using propylhexedrine products can include hospitalization, disability, or even death.[11] Public health agencies such as the FDA have advised propylhexedrine products only be used in the manners directed on their label.[11]

Overdose

Reports of overdoses from propylhexedrine have been documented, but they are uncommon.[15] Most instances of overdoses attributed to propylhexedrine have been the result of improper use of a propylhexedrine product in a manner not intended by its labeling for (non-medical) recreational purposes.[12] As noted by the FDA, the most common symptoms of propylhexedrine overdose are the following: "...[R]apid heart rate, agitation, high blood pressure, chest pain, tremor, hallucinations, delusions, confusion, nausea, and vomiting."[12] The use of propylhexedrine products in manners inconsistent with their labeling has proven fatal in some cases.[16][17] Propylhexedrine products are considered to be safe and effective if used as intended.[12] Regardless, medical attention should be sought in the case of suspected overdose.[18]

Interactions

As referred to earlier, most of propylhexedrine's interactions with other medications have to do with its ability to constrict blood vessels. This means that propylhexedrine may interact adversely with certain stimulants, bronchodilators, sympathomimetics, nasal decongestants, and antidepressants. Caution should be exercised when administering propylhexedrine concurrently with other medicines.[19]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Propylhexedrine works mainly as an adrenergic agonist, when used at therapeutic doses in an inhaler dosage form.[19] This restricts the blood vessels in the nose and reduces swelling; thereby, the product relieves nasal congestion.[20] At higher doses, propylhexedrine affects the central nervous system as a norepinephrine–dopamine releasing agent.[21] Propylhexedrine likely exerts such effects in a manner similar to related alkylamines such as cyclopentamine, methylhexanamine, and tuaminoheptane.[22][23][24] In addition, propylhexedrine further releases monoamines through TAAR1 agonism and VMAT2 inhibition.[19] Propylhexedrine also exhibits antihypotensive effects.[25]

Pharmacokinetics

Propylhexedrine undergoes metabolism to form various metabolites such as norpropylhexedrine, cyclohexylacetoxime, cyclohexylacetone, and 4-hydroxypropylhexedrine.[26]

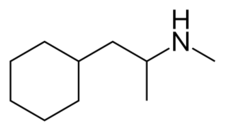

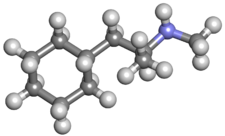

Chemistry

Freebase propylhexedrine is a volatile, oily liquid at room temperature. The slow evaporation of freebase propylhexedrine allows it to be administered via inhalation.[28] The evaporation of the freebase also accounts for the limited shelf-life of propylhexedrine inhalers. Many of the salts of propylhexedrine are stable, clear to off-white crystalline substances that readily dissolve in water.[29]

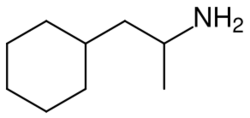

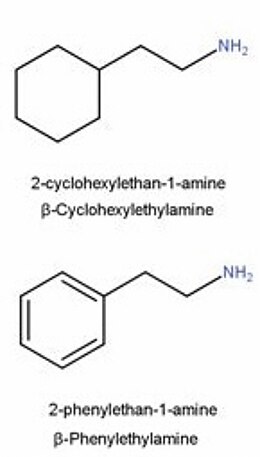

Propylhexedrine is similar in chemical structure to phenylethylamines. The main difference is the presence of an alicyclic cyclohexyl group instead of the aromatic phenyl group of a phenethylamine.

Propylhexedrine is a chiral compound. The active ingredient contained in Benzedrex inhalers is racemic (RS)-propylhexedrine as the free base.[30] (S)-Propylhexedrine, also known as levopropylhexedrine, is believed to be the more biologically active isomer of the two.[31] The dextrorotatory counterpart, which is mainly unused, is dextropropylhexedrine.

Synthesis

Propylhexedrine can be synthesized from cyclohexylacetone through the reductive amination of an intermediary imine over an aluminum-mercury amalgam in the presence of a hydrogen source.[32]

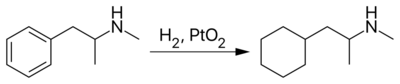

However, propylhexedrine is more commonly prepared by the catalytic hydrogenation of methamphetamine over Adams' catalyst. This transforms methamphetamine's phenyl ring to a cyclohexyl moiety.

Detection in bodily fluids

Due to its structure, administration of propylhexedrine can lead to false-positives for phenethylamine-derivatives on urinalysis panels.[34] Propylhexedrine can be differentiated upon further analysis.[35]

History

Propylhexedrine's medical use as a decongestant evolved from desires to find safer alternatives to previous agents.[36] After searching for such an agent, Dr. Glenn E. Ullyot patented propylhexedrine as a decongestant in 1948. This patent was issued for benefit of Smith, Kline & French.[37] Before it was sold nationally in the United States, propylhexedrine underwent market trials in California. These market trials began on July 15, 1949.[38] Propylhexedrine (under the brand-name Benzedrex) was first introduced into interstate commerce on August 4, 1949.[39]

Approval for use in the United Kingdom soon followed in 1956.[15] Later, approval for use in Canada was granted in 1998.[40] In 2023, B. F. Ascher & Co. decreased the amount of propylhexedrine in the Benzedrex inhaler from its historic 250 milligrams down to 175 milligrams.[41]

Barbexaclone, an anticonvulsant containing propylhexedrine, was used in Turkey until its withdrawal from the market in 2009. Barbexaclone's former niche in Turkish medicine is now largely-occupied by levetiracetam.[42]

Manufacturing

The manufacture of propylhexedrine products for therapeutic use is typically performed based on guidelines established in government regulations and pharmacopeia monographs.[43][3]

The illicit manufacture or diversion of propylhexedrine by clandestine chemists for use as a recreational drug has been documented in academic literature.[35] Similar to when opioids are manufactured clandestinely for recreational use, it is unlikely that propylhexedrine products manufactured by clandestine chemists are made to the standards for purity, identity, and strength required of therapeutic products.[44]

Society and culture

Legal status

International control

Propylhexedrine was placed under international control by the Convention on Psychotropic Substances in 1985. This action was reversed in 1991.[45]

Australia

Propylhexedrine is an S4 substance in Australia .[46]

Brazil

Propylhexedrine is a Class B1 substance in Brazil .[47]

Canada

Propylhexedrine is reported to be a Schedule V substance in Canada .[48]

Germany

Propylhexedrine is regulated as a prescription medicine in Germany .[49] Initially, propylhexedrine products (namely Obesin) were available over-the-counter. However, this changed in the 1970s and propylhexedrine is now regulated as a prescription product in Germany.[5]

United Kingdom

It was formerly a Class C substance in the United Kingdom, but was deregulated in 1995.[50] Propylhexedrine was used recreationally during a brief period in the 1970s after increased government regulation on earlier decongestants due to misuse.[51]

United States

On the 4th of April 1988, propylhexedrine was designated a controlled substance (Schedule V) in the United States .[52] This was done to satisfy U.S. compliance with an international treaty. However, in 1991, this action was reversed and propylhexedrine was removed from control under the Controlled Substances Act. This was based on the opinion of the Drug Enforcement Administration that propylhexedrine did not warrant control.[53] The substance has remained unregulated under the Controlled Substances Act in the United States ever since. Furthermore, pursuant to DEA regulations, certain Benzedrex inhalers are specifically exempt from the Controlled Substances Act.[54][55] Propylhexedrine remains regulated under the laws of several U.S. states. These states include the states of Alaska,[56] Arizona,[57] Florida,[58] Georgia,[59] Idaho,[60] Kansas,[61] and Rhode Island.[62]

Recreational use

Multiple public health agencies (most notably within the United States) have warned against the recreational use of propylhexedrine and advised for its use only as directed by a product's labeling; nonetheless it has been reported, through the literature as early as 1959, that propylhexedrine products have been used for recreational purposes.[63] Recreational use is potentially fatal, its risks are magnified when administering the substance through injection means, and the adverse effects of recreational propylhexedrine are more severe when compared to related substances.[64][65][66] The undesirable side effects of propylhexedrine at recreational doses are less tolerable compared to other substances that produce similar effects; consequently, making propylhexedrine less desirable for recreational use.[18][67][16] The fact that propylhexedrine is less potent than comparable substances has also limited recreational use.[68][69] Even in areas with prevalent substance use, the use of propylhexedrine was reported as non-significant.[15] The recreational use of nasal decongestant,[67][70] anorectic,[63] and anticonvulsant preparations[71] have all been reported. The recreational use of propylhexedrine products has been on the rise since the early 2000s.[21]

In 2021, the United States Food & Drug Administration issued the following warning[12] in regard to recreational use of propylhexedrine products in manners inconsistent with their labeling:

"...[T]he abuse and misuse of the over-the-counter (OTC) nasal decongestant propylhexedrine can lead to serious harm such as heart and mental health problems. Some of these complications, which include fast or abnormal heart rhythm, high blood pressure, and paranoia, can lead to hospitalization, disability, or death....Propylhexedrine is safe and effective when used as directed."

That same year, the Indian Health Service issued the following statement[13] in reference to the recreational use of propylhexedrine products:

"Only use propylhexedrine according to the instructions on the package label. Do not use it in ways other than inhalation. Seek medical attention immediately for by calling [emergency services] or Poison Control...for anyone using propylhexedrine who experiences [the following.] [These following reactions are] [s]evere anxiety or agitation, confusion, hallucinations, or paranoia[,] [r]apid heartbeat or abnormal heart rhythm[,] [or] [c]hest pain or tightness[.]"

A year later, in 2022, the U.S. Army published the following guidance[14] on propylhexedrine. The guidance states that recreational use of propylhexedrine is not permissible by service-members, can open its participants up to disciplinary action, and carries potentially fatal risks:

"When disciplining a member for suspected use of any drug, it is important to consult [legal counsel] on how to proceed, [according to the Office of Drug Demand Reduction]...This is especially important when the evidence supporting discipline consists of scientific reports and data that may require special assistance in their interpretation. In cases involving [propylhexedrine], legal consultation is highly recommended."

Summarily, the Food & Drug Administration, Indian Health Service, and U.S. Army all advise individuals not to use propylhexedrine products for recreational purposes. In spite of the known risks and warnings such as these, communities dedicated to discussing recreational propylhexedrine use exist online through platforms such as Reddit.[21]

Economics

Propylhexedrine, under the brand name Benzedrex, is sold online by retailers such as Amazon, eBay, and Walmart.[30] Propylhexedrine has been sold in some countries as an anorectic or as part of an anticonvulsant preparation; however, such products are not sold freely to consumers and require a physician's prescription.

Brand names

Benzedrex inhaler

Propylhexedrine, as a nasal decongestant, is currently marketed under the trade name Benzedrex. The name Benzedrex was initially trademarked by Smith, Kline & French in 1944.[72] The brand was passed onto Menley James Laboratories (through a subsidiary, NuMark Laboratories) in 1990, and was finally acquired by B. F. Ascher & Co. in 1998.[73][74]

Dristan inhaler

Propylhexedrine was also sold in inhaler form by Whitehall Laboratories under the Dristan brand name as an inhaler.[75] In January 1966, propylhexedrine replaced mephentermine as the active ingredient in the product.[76] The Dristan inhaler has since been discontinued. Furthermore, Wyeth was acquired by Pfizer in 2009. All products currently sold under the Dristan brand are manufactured by Foundation Consumer Brands; Foundation Consumer Brands acquired the Dristan brand in 2020.[77] Foundation Consumer Brands is itself owned by Kelso & Company.

Obesin

Propylhexedrine has also seen use in Europe as an appetite suppressant, under the trade name Obesin.[38] Obesin has been referenced in literature dating back to the 1950s.[10][63] Obesin was manufactured by Fahlberg-List in East Germany from 1958 to around 1976. The discontinuation of Obesin was the result of increased regulatory restrictions on over-the-counter anorectics. These restrictions began to be imposed in 1974.[5] Fahlberg-List itself dissolved in 1995.

Maliasin

Propylhexedrine is a component in the anticonvulsant preparation barbexaclone. Its S-isomer (levopropylhexedrine or L-propylhexedrine) is bonded with phenobarbital for the purpose of offsetting the barbiturate-induced sedation.[38] Barbexaclone has been known under the brand name of Maliasin, manufactured by Abbott Laboratories, as early as 1965.[78][79] Maliasin has also been manufactured by Knoll Pharmaceuticals; Knoll is a company acquired by Abbott Laboratories. In 2010, Abbott discontinued sale of its barbexaclone preparation in many countries.[80]

Eventin

Levopropylhexedrine (the more active optical isomer of propylhexedrine) has been used as an appetite suppressant under the brand name Eventin. Eventin's use has been documented as early as 1958.[81]

References

- ↑ "Cold, Cough, Allergy, Bronchodilator, and Antiasthmatic Drug Products for Over-the-Counter Human Use". June 7, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=341.20.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "BENZEDREX 09-19-2014- propylhexedrine inhalant". Daily Med. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/fda/fdaDrugXsl.cfm?setid=03a8ef3c-a808-6208-e054-00144ff8d46c.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "USP Monographs: Propylhexedrine Inhalant". https://doi.usp.org/USPNF/USPNF_M71100_01_01.html.

- ↑ Docherty, J. R. (June 2008). "Pharmacology of stimulants prohibited by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA)". British Journal of Pharmacology 154 (3): 606–622. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.124. PMID 18500382.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Winter, E. (1976). "Bemerkungen zu Drogenmißbrauch und -abhängigkeit vom Amphetamin- Typ unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des Amphetaminils (Aponeuron (R) )" (in DE). Psychiatrie, Neurologie und medizinische Psychologie 28 (9): 513–525. ISSN 0033-2739. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45253962.

- ↑ "NCATS Inxight Drugs — PROPYLHEXEDRINE HYDROCHLORIDE" (in en). https://drugs.ncats.io/drug/064LUN7NZ5.

- ↑ "Propylhexedrine Contraindications". Medscape. http://reference.medscape.com/drug/benzedrex-propylhexedrine-343411.

- ↑ Terrie, Y. C. (December 20, 2017). Decongestants and Hypertension: Making Wise Choices When Selecting OTC Medications. December 2017 Heart Health. 83. https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/decongestants-and-hypertension-making-wise-choices-when-selecting-otc-medications. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ↑ "Propylhexedrine" (in en). Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. https://www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/patient-education/medications/adult/propylhexedrine.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Polster, H. (February 1965). "[On Poisoning With the Appetite Depressant Propylhexedrine, "Obesin" in a 3-Year-Old Child]". Archiv für Toxikologie 20: 271–273. doi:10.1007/BF00577551. PMID 14272412.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "Benzedrex (propylhexedrine): Drug Safety Communication". March 25, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/safety/medical-product-safety-information/benzedrex-propylhexedrine-drug-safety-communication-fda-warns-abuse-and-misuse-nasal-decongestant.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (2021-04-15). "FDA warns that abuse and misuse of the nasal decongestant propylhexedrine causes serious harm" (in en). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-warns-abuse-and-misuse-nasal-decongestant-propylhexedrine-causes-serious-harm.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Abuse and Misuse of Propylhexedrine Nasal Decongestant Causes Serious Harm" (in en). Indian Health Service. 2021. https://www.ihs.gov/nptc/pharmacovigilance/medication-safety-resources-archive/2021/abuse-and-misuse-of-propylhexedrine-nasal-decongestant-causes-serious-harm/.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Parrish, A. (October 26, 2022). "FDA issues drug misuse guidance" (in en). https://www.army.mil/article/261494/fda_issues_drug_misuse_guidance.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Smith, D. E.; Wesson, D. R.; Morgan, J. P. (1988-10-01). "An epidemiological and clinical analysis of propylhexedrine abuse in the United States". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 20 (4): 441–442. doi:10.1080/02791072.1988.10472514. PMID 2907528.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Sturner, W. Q.; Spruill, F. G.; Garriott, J. C. (July 1974). "Two propylhexedrine-associated fatalities: Benzedrine revisited". Journal of Forensic Sciences 19 (3): 572–574. doi:10.1520/JFS10213J. PMID 4137337. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4137337/.

- ↑ "RISE IN NASAL INHALER ABUSE WORRIES OFFICIALS" (in en-US). The New York Times: pp. 34. 1985-09-22. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/1985/09/22/us/rise-in-nasal-inhaler-abuse-worries-officials.html.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Propylhexedrine (Benzedrex)" (in en). https://www.poison.org/articles/propylhexedrine.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 "Propylhexedrine". DrugBank. http://www.drugbank.ca/drugs/DB06714.

- ↑ "Decongestants" (in en). 2017-10-18. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/decongestants/.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Teja, N.; Dodge, C. P.; Stanciu, C. N. (October 2020). "Abuse, Toxicology and the Resurgence of Propylhexedrine: A Case Report and Review of Literature". Cureus 12 (10): e10868. doi:10.7759/cureus.10868. PMID 33178521.

- ↑ Small, C.; Cheng, M. H.; Belay, S. S.; Bulloch, S. L.; Zimmerman, B.; Sorkin, A.; Block, E. R. (August 2023). "The Alkylamine Stimulant 1,3-Dimethylamylamine Exhibits Substrate-Like Regulation of Dopamine Transporter Function and Localization". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 386 (2): 266–273. doi:10.1124/jpet.122.001573. PMID 37348963.

- ↑ Schmidt, J. L.; Fleming, W. W. (July 1964). "A Nonsympathomimetic Effect of Cyclopentamine and Beta-Mercaptoethylamine in the Rabbit Ileum". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 145: 83–86. PMID 14209515.

- ↑ Delicado, E. G.; Fideu, M. D.; Miras-Portugal, M. T.; Pourrias, B.; Aunis, D. (August 1990). "Effect of tuamine, heptaminol and two analogues on uptake and release of catecholamines in cultured chromaffin cells". Biochemical Pharmacology 40 (4): 821–825. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(90)90322-c. PMID 2386550.

- ↑ Lands, A. M.; Nash, V. L. (April 1947). "The pharmacologic activity of N-methyl-beta-cyclohexyl-isopropylamine hydrochloride". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 89 (4): 382–385. PMID 20295519. https://jpet.aspetjournals.org/content/89/3/382.

- ↑ Midha, K. K.; Beckett, A. H.; Saunders, A. (October 1974). "Identification of the major metabolites of propylhexedrine in vivo (in man) and in vitro (in guinea pig and rabbit)". Xenobiotica; the Fate of Foreign Compounds in Biological Systems 4 (10): 627–635. doi:10.1080/00498257409169765. PMID 4428789.

- ↑ Schaiberger, P. H.; Kennedy, T. C.; Miller, F. C.; Gal, J.; Petty, T. L. (August 1993). "Pulmonary Hypertension Associated With Long-term Inhalation of "Crank" Methamphetamine". Chest 104 (2): 614–616. doi:10.1378/chest.104.2.614. ISSN 0012-3692. PMID 8101799. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.104.2.614.

- ↑ Grayson, M., "Nasal Inhaler", US patent granted 4095596, issued 20 June 1978, assigned to Smithkline Corp.

- ↑ Mancusi-Ungaro, H. R.; Decker, W. J.; Forshan, V. R.; Blackwell, S. J.; Lewis, S. R. (1983). "Tissue injuries associated with parenteral propylhexedrine abuse". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology 21 (3): 359–372. doi:10.1097/00005373-198307000-00114. PMID 6144800.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "Benzedrex Inhaler". https://www.bfascher.com/products/benzedrex/.

- ↑ Lands, A. M.; Nash, V. L.; Granger, H. R.; Dertinger, B. L. (April 1947). "The pharmacologic activity of N-methyl-beta-cyclohexyl-isopropylamine hydrochloride". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 89 (4): 382–385. PMID 20295519. http://jpet.aspetjournals.org/content/89/3/382.short.

- ↑ Lednicer, D.; Mitscher, L. A. (1977). Organic Chemistry of Drug Synthesis. 1. New York, NY: Wiley. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-471-52141-9.

- ↑ Zenitz, B. L.; Macks, E. B.; Moore, M. L. (May 1947). "Preparation of some primary and secondary beta-cyclohexylalkylamines". Journal of the American Chemical Society 69 (5): 1117–1121. doi:10.1021/ja01197a039. PMID 20240502.

- ↑ Thurman, E. M.; Pedersen, M. J.; Stout, R. L.; Martin, T. (1992). "Distinguishing sympathomimetic amines from amphetamine and methamphetamine in urine by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry". Journal of Analytical Toxicology 16 (1): 19–27. doi:10.1093/jat/16.1.19. PMID 1640694.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Johnson, P.; Briner, R. C. (October 1992). "A Clandestine Laboratory Extracting Propylhexedrine from Benzedrex Inhalers". Journal of the Clandestine Laboratory Investigating Chemists Association 2 (4): 25–28. https://bitnest.netfirms.com/external/JCLIC/2.4.25-28.

- ↑ Schwarez, J.. "Sniffing Benzedrine Inhalers" (in en). McGill University. https://www.mcgill.ca/oss/article/medical-health-and-nutrition/sniffing-benzedrine-inhalers.

- ↑ , G. E."Cyclohexylalkylamines" patent US2454746A, issued 1948-11-23

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Wesson, D. R. (June 1986). "Propylhexdrine". Drug and Alcohol Dependence 17 (2–3): 273–278. doi:10.1016/0376-8716(86)90013-X. PMID 2874970.

- ↑ Grant, G. (August 4, 1949). "Extension of remarks by representative Grant on H.R. 2969 - Bezedrine Inhalers". Government Publishing Office. p. A5052. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1949-pt15/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1949-pt15-1.pdf.

- ↑ "Propylhexedrine - NAPRA" (in en-US). https://www.napra.ca/nds/propylhexedrine/.

- ↑ "DailyMed - BENZEDREX- propylhexedrine inhalant (06/23/2023)". U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=00d8c237-3eee-1d9f-e063-6394a90aeb86.

- ↑ Bolukbasi, F.; Delil, S.; Bulus, E.; Senturk, A.; Yeni, N.; Karaagac, N. (September 2013). "End of the barbexaclone era: an experience of treatment withdrawal". Epileptic Disorders 15 (3): 311–313. doi:10.1684/epd.2013.0605. PMID 23981808.

- ↑ "Federal Register Vol. 41, No. 176". September 9, 1976. pp. 38402. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-1976-09-09/pdf/FR-1976-09-09.pdf.

- ↑ Collier, R. (2013-09-03). "Street versions of opioids more potent and dangerous" (in en). CMAJ 185 (12): 1027. doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-4535. ISSN 0820-3946. PMID 23836854. PMC 3761004. https://www.cmaj.ca/content/185/12/1027.

- ↑ "Expert Committee on Drug Dependence's Twenty-Seventh Report". Expert Committee on Drug Dependence. September 28, 1990. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/40616/WHO_TRS_808.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- ↑ "Schedule 4 Appendix D drugs - Prescribed restricted substances - Pharmaceutical services" (in en). https://www.health.nsw.gov.au:443/pharmaceutical/Pages/sch4d.aspx.

- ↑ Anvisa (2023-03-31). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" (in pt-BR). Diário Oficial da União. https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/resolucao-rdc-n-784-de-31-de-marco-de-2023-474904992.

- ↑ "Erowid Propylhexedrine (Benzedrex) Vault : Law". https://www.erowid.org/pharms/propylhexedrine/propylhexedrine_law.shtml.

- ↑ "Anlage 1 AMVV - Einzelnorm". https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/amvv/anlage_1.html.

- ↑ "The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (Modification) Order 1995". Office of Public Sector Information. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1995/1966/contents/made.

- ↑ Wilson, A. (2016-03-23). "The blanket drugs ban is necessary, but won't solve the bigger problem – as I know from personal experience" (in en-US). http://theconversation.com/the-blanket-drugs-ban-is-necessary-but-wont-solve-the-bigger-problem-as-i-know-from-personal-experience-56237.

- ↑ Lawn, J. (April 4, 1988). "Schedules of Controlled Substances: Placement of Propylhexedrine and Pyrovalerone into Schedule V". Drug Enforcement Administration. https://isomerdesign.com/Cdsa/FR/53FR10869.pdf.

- ↑ Bonner, R. (December 3, 1991). "Schedules of Controlled Substances: Removal of Propylhexedrine From Control". Drug Enforcement Administration. https://isomerdesign.com/Cdsa/FR/56FR61372.pdf.

- ↑ "Sec. 1308.22 Excluded substances.". Drug Enforcement Administration. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=1308.22.

- ↑ Haislip, G. (January 11, 1989). "Excluded Non-narcotic Over-the-counter Substances". Drug Enforcement Administration. https://archives.federalregister.gov/issue_slice/1989/1/19/2099-2101.pdf#page=2.

- ↑ "2014 Alaska Statutes :: Title 11 - CRIMINAL LAW :: Chapter 11.71 - CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES :: Article 02 - STANDARDS AND SCHEDULES :: Sec. 11.71.180 Schedule VA." (in en). https://law.justia.com/codes/alaska/2014/title-11/chapter-11.71/article-02/section-11.71.180.

- ↑ "2005 Arizona Revised Statutes - :: Revised Statutes §13-3401 Definitions" (in en). https://law.justia.com/codes/arizona/2005/title13/03401.html.

- ↑ "2011 Florida Statutes :: TITLE XLVI — CRIMES :: Chapter 893 — DRUG ABUSE PREVENTION AND CONTROL :: 893.03 — Standards and schedules." (in en). https://law.justia.com/codes/florida/2011/titlexlvi/chapter893/section893.03.

- ↑ "2022 Georgia Code :: Title 16 - Crimes and Offenses :: Chapter 13 - Controlled Substances :: Article 2 - Regulation of Controlled Substances :: Part 1 - Schedules, Offenses, and Penalties :: § 16-13-29.1. Nonnarcotic Substances Excluded From Schedules of Controlled Substances" (in en). https://law.justia.com/codes/georgia/2022/title-16/chapter-13/article-2/part-1/section-16-13-29-1/.

- ↑ "2010 Idaho Code :: TITLE 37 FOOD, DRUGS, AND OIL :: CHAPTER 27 UNIFORM CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES :: ARTICLE II :: 37-2713 SCHEDULE V." (in en). https://law.justia.com/codes/idaho/2010/title37/t37ch27sect37-2713.html.

- ↑ "2017 Kansas Statutes :: Chapter 65 PUBLIC HEALTH :: Article 41 CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES :: 65-4113 Substances included in schedule V." (in en). https://law.justia.com/codes/kansas/2021/chapter-65/article-41/section-65-4113/.

- ↑ "2021 Rhode Island General Laws :: Title 21 - Food and Drugs :: Chapter 21-28 - Uniform Controlled Substances Act :: Section 21-28-2.08 - Contents of schedules." (in en). https://law.justia.com/codes/rhode-island/2021/title-21/chapter-21-28/section-21-28-2-08/.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 Rose, W. (September 1959). "Arzneimittelsucht durch Mißbrauch von sogenannten Appetitzüglern (Obesin)" (in de). Archiv für Toxikologie 17 (5): 331–335. doi:10.1007/BF00577633. ISSN 1432-0738. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00577633.

- ↑ Fornazzari, L.; Carlen, P. L.; Kapur, B. M. (November 1986). "Intravenous abuse of propylhexedrine (Benzedrex) and the risk of brainstem dysfunction in young adults". The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. Le Journal Canadien des Sciences Neurologiques 13 (4): 337–339. doi:10.1017/S0317167100036696. PMID 2877725.

- ↑ "Propylhexedrine (hydrochloride)". Safety Data Sheet. Cayman Chemical. https://www.caymanchem.com/msdss/12058m.pdf.

- ↑ Holler, J. M.; Vorce, S. P.; McDonough-Bender, P. C.; Magluilo, J.; Solomon, C. J.; Levine, B. (January 2011). "A drug toxicity death involving propylhexedrine and mitragynine". Journal of Analytical Toxicology 35 (1): 54–59. doi:10.1093/anatox/35.1.54. PMID 21219704.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Anderson, E. D. (May 1970). "Propylhexedrine (Benzedrex) psychosis". The New Zealand Medical Journal 71 (456): 302. PMID 5270979.

- ↑ Cooper, D.. ""Future Synthetic Drugs of Abuse"". Drug Enforcement Administration. https://www.erowid.org/library/books_online/future_synthetic/.

- ↑ Garriott, J. C. (1975). "Editorial: Propylhexadrine - a new dangerous drug?". Clinical Toxicology 8 (6): 665–666. doi:10.3109/15563657508990092. PMID 6189.

- ↑ Curry, B. (September 5, 1985). "Abuse of Potentially Fatal Nasal Inhaler Medication by Injection Called Widespread". LA Times. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1985-09-05-mn-24755-story.html.

- ↑ Darcın, A. E.; Dilbaz, N.; Okay, I. T. (October 2010). "Barbexaclone abuse in a cannabis ex-user". Substance Abuse 31 (4): 270–272. doi:10.1080/08897077.2010.514246. PMID 21038181.

- ↑ "BENZEDREX Trademark of B.F. ASCHER & COMPANY INC - Registration Number 0896775 - Serial Number 72340742" (in en). http://trademarks.justia.com/723/40/benzedrex-72340742.html.

- ↑ Robertson, V. (February 17, 2004). "Prince v. B.F. Ascher Company, Inc., 90 P.3d 1020 (Okla. Civ. App. 2004)". https://casetext.com/case/prince-v-bf-ascher-company-inc.

- ↑ "B.F. Ascher marks 50th year. - Free Online Library". Chain Drug Review. March 1, 1999. https://www.thefreelibrary.com/B.F.+Ascher+marks+50th+year.-a054082926.

- ↑ "ACTION IN RESPECT OF INTERNATIONAL CONVENTIONS ON NARCOTIC DRUGS AND PSYCHOTROPIC SUBSTANCES". November 24, 1989. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/163484/EB85_23_eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- ↑ Angrist, B. M.; Schweitzer, J. W.; Gershon, S.; Friedhoff, A. J. (March 1970). "Mephentermine psychosis: misuse of the Wyamine inhaler". The American Journal of Psychiatry 126 (9): 1315–1317. doi:10.1176/ajp.126.9.1315. PMID 5413209.

- ↑ "Foundation Consumer Healthcare to Add Seven Over-the-Counter Brands to Expanding Portfolio of Healthcare Products". Kelso & Company. October 1, 2020. https://foundationch.com/assets/press-release/2020-10-01.pdf.

- ↑ Krueger, H. J.; Schwarz, H. (April 1965). "[Clinical Communication on the Therapy of Epilepsy With Maliasin]". Die Medizinische Welt 14: 690–692. PMID 14276849.

- ↑ "MALIASIN Trademark - Registration Number 0797076 - Serial Number 72213021" (in en). http://trademarks.justia.com/722/13/maliasin-72213021.html.

- ↑ Serracchiani, D. (January 31, 2011). "Parliamentary question | Maliasin | P-001035/2011 | European Parliament" (in en). https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/P-7-2011-001035_EN.html.

- ↑ Hofer, R.; Locker, A. (April 1958). "[Therapeutic experiences with the appetite depressant eventin"]. Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift 108 (14): 304–306. PMID 13558159. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/13558159/.

|