Chemistry:Carbamazepine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Tegretol, others |

| Other names | CBZ |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682237 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Anticonvulsant[1] |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ~100%[3] |

| Protein binding | 70–80%[3] |

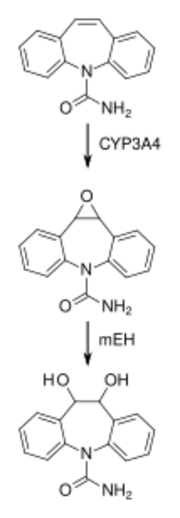

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP3A4)[3] |

| Metabolites | Active epoxide form (carbamazepine-10,11 epoxide)[3] |

| Elimination half-life | 36 hours (single dose), 16–24 hours (repeated dosing)[3] |

| Excretion | Urine (72%), feces (28%)[3] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

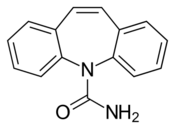

| Formula | C15H12N2O |

| Molar mass | 236.274 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Carbamazepine, sold under the brand name Tegretol among others, is an anticonvulsant medication used in the treatment of epilepsy and neuropathic pain.[2][1] It is used as an adjunctive treatment in schizophrenia along with other medications and as a second-line agent in bipolar disorder.[4][1] Carbamazepine appears to work as well as phenytoin and valproate for focal and generalized seizures.[5] It is not effective for absence or myoclonic seizures.[1]

Carbamazepine was discovered in 1953 by Swiss chemist Walter Schindler.[6][7] It was first marketed in 1962.[8] It is available as a generic medication.[9] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[10] In 2020, it was the 185th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 2 million prescriptions.[11][12]

Medical uses

Carbamazepine is typically used for the treatment of seizure disorders and neuropathic pain.[1] It is used off-label as a second-line treatment for bipolar disorder and in combination with an antipsychotic in some cases of schizophrenia when treatment with a conventional antipsychotic alone has failed.[1][13] However, evidence does not support its usage for schizophrenia.[14] It is not effective for absence seizures or myoclonic seizures.[1] Although carbamazepine may have a similar effectiveness (as measured by people continuing to use a medication) and efficacy (as measured by the medicine reducing seizure recurrence and improving remission) when compared to phenytoin and valproate, choice of medication should be evaluated on an individual basis as further research is needed to determine which medication is most helpful for people with newly-onset seizures.[5]

In the United States, carbamazepine is indicated for the treatment of epilepsy (including partial seizures, generalized tonic-clonic seizures and mixed seizures), and trigeminal neuralgia.[2][15] Carbamazepine is the only medication that is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia.[16]

As of 2014, a controlled release formulation was available for which there is tentative evidence showing fewer side effects and unclear evidence with regard to whether there is a difference in efficacy.[17]

Adverse effects

In the US, the label for carbamazepine contains warnings concerning:[2]

- effects on the body's production of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets: rarely, there are major effects of aplastic anemia and agranulocytosis reported and more commonly, there are minor changes such as decreased white blood cell or platelet counts, but these do not progress to more serious problems.[3]

- increased risks of suicide[18]

- increased risks of hyponatremia and SIADH[3][19]

- risk of seizures, if the person stops taking the drug abruptly[3]

- risks to the fetus in women who are pregnant, specifically congenital malformations like spina bifida, and developmental disorders.[3][20]

- Pancreatitis

- Hepatitis

- Dizziness

- Bone marrow suppression

- Stevens–Johnson syndrome

Common adverse effects may include drowsiness, dizziness, headaches and migraines, ataxia, nausea, vomiting, and/or constipation. Alcohol use while taking carbamazepine may lead to enhanced depression of the central nervous system.[3] Less common side effects may include increased risk of seizures in people with mixed seizure disorders,[21] abnormal heart rhythms, blurry or double vision.[3] Also, rare case reports of an auditory side effect have been made, whereby patients perceive sounds about a semitone lower than previously; this unusual side effect is usually not noticed by most people, and disappears after the person stops taking carbamazepine.[22]

In a systematic review, the authors identified seventy-three reports containing one-hundred ninety-one individuals who developed movement disorders associated with carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and eslicarbazepine. The abnormal movements encountered were myoclonus, dystonia, tics, dyskinesia, parkinsonism, akathisia, and unclear incoordination.[23]

Pharmacogenetics

Serious skin reactions such as Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) or toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) due to carbamazepine therapy are more common in people with a particular human leukocyte antigen gene-variant (allele), HLA-B*1502.[3] Odds ratios for the development of SJS or TEN in people who carry the allele can be in the double, triple or even quadruple digits, depending on the population studied.[24][25] HLA-B*1502 occurs almost exclusively in people with ancestry across broad areas of Asia, but has a very low or absent frequency in European, Japanese, Korean and African populations.[3][26] However, the HLA-A*31:01 allele has been shown to be a strong predictor of both mild and severe adverse reactions, such as the DRESS form of severe cutaneous reactions, to carbamazepine among Japanese, Chinese, Korean, and Europeans.[25][27] It is suggested that carbamazepine acts as a potent antigen that binds to the antigen-presenting area of HLA-B*1502 alike, triggering an everlasting activation signal on immature CD8-T cells, thus resulting in widespread cytotoxic reactions like SJS/TEN.[28]

Interactions

Carbamazepine has a potential for drug interactions.[15] Drugs that decrease breaking down of carbamazepine or otherwise increase its levels include erythromycin,[29] cimetidine, propoxyphene, and calcium channel blockers.[15] Grapefruit juice raises the bioavailability of carbamazepine by inhibiting the enzyme CYP3A4 in the gut wall and in the liver.[3] Lower levels of carbamazepine are seen when administered with phenobarbital, phenytoin, or primidone, which can result in breakthrough seizure activity.[30]

Valproic acid and valnoctamide both inhibit microsomal epoxide hydrolase (mEH), the enzyme responsible for the breakdown of the active metabolite carbamazepine-10,11-epoxide into inactive metabolites.[31] By inhibiting mEH, valproic acid and valnoctamide cause a build-up of the active metabolite, prolonging the effects of carbamazepine and delaying its excretion.

Carbamazepine, as an inducer of cytochrome P450 enzymes, may increase clearance of many drugs, decreasing their concentration in the blood to subtherapeutic levels and reducing their desired effects.[30] Drugs that are more rapidly metabolized with carbamazepine include warfarin, lamotrigine, phenytoin, theophylline, valproic acid,[15] many benzodiazepines,[32] and methadone.[33] Carbamazepine also increases the metabolism of the hormones in birth control pills and can reduce their effectiveness, potentially leading to unexpected pregnancies.[15]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Carbamazepine is a sodium channel blocker.[34] It binds preferentially to voltage-gated sodium channels in their inactive conformation, which prevents repetitive and sustained firing of an action potential. Carbamazepine has effects on serotonin systems but the relevance to its antiseizure effects is uncertain. There is evidence that it is a serotonin releasing agent and possibly even a serotonin reuptake inhibitor.[35][36][37] It has been suggested that carbamazepine can also block voltage-gated calcium channels, which will reduce neurotransmitter release.[38]

Pharmacokinetics

Carbamazepine is relatively slowly but practically completely absorbed after administration by mouth. Highest concentrations in the blood plasma are reached after 4 to 24 hours depending on the dosage form. Slow release tablets result in about 15% lower absorption and 25% lower peak plasma concentrations than ordinary tablets, as well as in less fluctuation of the concentration, but not in significantly lower minimum concentrations.[39][40]

In the circulation, carbamazepine itself comprises 20 to 30% of total residues. The remainder is in the form of metabolites; 70 to 80% of residues is bound to plasma proteins. Concentrations in breast milk are 25 to 60% of those in the blood plasma.[40]

Carbamazepine itself is not pharmacologically active. It is activated, mainly by CYP3A4, to carbamazepine-10,11-epoxide, which is solely responsible for the drug's anticonvulsant effects. The epoxide is then inactivated by microsomal epoxide hydrolase (mEH) to carbamazepine-trans-10,11-diol and further to its glucuronides. Other metabolites include various hydroxyl derivatives and carbamazepine-N-glucuronide.[40]

The plasma half-life is about 35 to 40 hours when carbamazepine is given as single dose, but it is a strong inducer of liver enzymes, and the plasma half-life shortens to about 12 to 17 hours when it is given repeatedly. The half-life can be further shortened to 9–10 hours by other enzyme inducers such as phenytoin or phenobarbital. About 70% are excreted via the urine, almost exclusively in form of its metabolites, and 30% via the faeces.[39][40]

History

Carbamazepine was discovered by chemist Walter Schindler at J.R. Geigy AG (now part of Novartis) in Basel, Switzerland , in 1953.[41][42] It was first marketed as a drug to treat epilepsy in Switzerland in 1963 under the brand name Tegretol; its use for trigeminal neuralgia (formerly known as tic douloureux) was introduced at the same time.[41] It has been used as an anticonvulsant and antiepileptic in the United Kingdom since 1965, and has been approved in the United States since 1968.[1]

Carbamazepine was studied for bipolar disorder throughout the 1970s.[43]

Society and culture

Environmental impact

Carbamazepine and its bio-transformation products have been detected in wastewater treatment plant effluent[44]:224 and in streams receiving treated wastewater.[45] Field and laboratory studies have been conducted to understand the accumulation of carbamazepine in food plants grown in soil treated with sludge, which vary with respect to the concentrations of carbamazepine present in sludge and in the concentrations of sludge in the soil. Taking into account only studies that used concentrations commonly found in the environment, a 2014 review concluded that "the accumulation of carbamazepine into plants grown in soil amended with biosolids poses a de minimis risk to human health according to the approach."[44]:227

Brand names

Carbamazepine is available worldwide under many brand names including Tegretol.[46]

Research

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 "Carbamazepine". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. https://www.drugs.com/monograph/carbamazepine.html.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Tegretol- carbamazepine suspension Tegretol- carbamazepine tablet Tegretol XR- carbamazepine tablet, extended release". 16 May 2022. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=8d409411-aa9f-4f3a-a52c-fbcb0c3ec053.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 "Carbamazepine Drug Label". http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=7a1e523a-b377-43dc-b231-7591c4c888ea.

- ↑ "Sodium valproate versus phenytoin monotherapy for epilepsy: an individual participant data review". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018 (8): CD001769. August 2018. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001769.pub4. PMID 30091458.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Carbamazepine versus phenytoin monotherapy for epilepsy: an individual participant data review". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2019 (7): CD001911. July 2019. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001911.pub4. PMID 31318037.

- ↑ Current therapy in pain. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier. 2009. p. 460. ISBN 978-1-4160-4836-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=iTgy62MWnK4C&pg=PA460.

- ↑ "New n-heterocyclic compounds" US patent 2948718, published 1960-08-09, issued 1960-08-09, assigned to Geigy Chemical Corporation

- ↑ The treatment of epilepsy (3 ed.). Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. 2009. p. xxix. ISBN 978-1-4443-1667-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=rFFzFzZJtasC&pg=PR29.

- ↑ "Trigeminal Neuralgia: Surgical Perspective". Principles and practice of stereotactic radiosurgery. New York: Springer. 2008. p. 536. ISBN 978-0-387-71070-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=uEghr21XY6wC&pg=PA536.

- ↑ Organization, World Health (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ "The Top 300 of 2020". https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Top300Drugs.aspx.

- ↑ "Carbamazepine - Drug Usage Statistics". https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Carbamazepine.

- ↑ "Comparison of carbamazepine and lithium in treatment of bipolar disorder: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials". Human Psychopharmacology 24 (1): 19–28. January 2009. doi:10.1002/hup.990. PMID 19053079.

- ↑ "Carbamazepine for schizophrenia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014 (5): CD001258. May 2014. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001258.pub3. PMID 24789267.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Lexi-Comp (February 2009). "Carbamazepine". The Merck Manual Professional. http://www.merck.com/mmpe/lexicomp/carbamazepine.html. Retrieved on 3 May 2009.

- ↑ "Trigeminal Neuralgia: A "Lightning Bolt" of Pain". US Pharmacist 42: 41–44. 19 January 2017. https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/trigeminal-neuralgia-a-lightning-bolt-of-pain.

- ↑ "Immediate-release versus controlled-release carbamazepine in the treatment of epilepsy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 12 (4): CD007124. December 2016. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007124.pub5. PMID 27933615.

- ↑ "Neurostimulation for the treatment of chronic migraine and cluster headache". Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 139 (1): 4–17. January 2019. doi:10.1111/ane.13034. PMID 30291633.

- ↑ "Review of carbamazepine-induced hyponatremia". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry 18 (2): 211–33. March 1994. doi:10.1016/0278-5846(94)90055-8. PMID 8208974.

- ↑ "Intrauterine exposure to carbamazepine and specific congenital malformations: systematic review and case-control study". BMJ 341: c6581. December 2010. doi:10.1136/bmj.c6581. PMID 21127116.

- ↑ "The mechanism of carbamazepine aggravation of absence seizures". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 319 (2): 790–8. November 2006. doi:10.1124/jpet.106.104968. PMID 16895979.

- ↑ "Carbamazepine-induced transient auditory pitch-perception deficit". Pediatric Neurology 35 (2): 131–4. August 2006. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2006.01.011. PMID 16876011.

- ↑ "Carbamazepine-, Oxcarbazepine-, Eslicarbazepine-Associated Movement Disorder: A Literature Review". Clinical Neuropharmacology 43 (3): 66–80. May 2020. doi:10.1097/WNF.0000000000000387. PMID 32384309.

- ↑ "Pharmacogenomics of severe cutaneous adverse reactions and drug-induced liver injury". Journal of Human Genetics 58 (6): 317–26. June 2013. doi:10.1038/jhg.2013.37. PMID 23635947.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "Recommendations for HLA-B*15:02 and HLA-A*31:01 genetic testing to reduce the risk of carbamazepine-induced hypersensitivity reactions". Epilepsia 55 (4): 496–506. April 2014. doi:10.1111/epi.12564. PMID 24597466.

- ↑ "Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for HLA-B genotype and carbamazepine dosing". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 94 (3): 324–8. September 2013. doi:10.1038/clpt.2013.103. PMID 23695185.

- ↑ "Pharmacogenomics of off-target adverse drug reactions". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 83 (9): 1896–1911. September 2017. doi:10.1111/bcp.13294. PMID 28345177.

- ↑ "HLA-B*15:21 and carbamazepine-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome: pooled-data and in silico analysis". Scientific Reports 7 (1): 45553. March 2017. doi:10.1038/srep45553. PMID 28358139. Bibcode: 2017NatSR...745553J.

- ↑ "Erythromycin-induced carbamazepine toxicity: a continuing problem". Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 149 (1): 99–101. January 1995. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1995.02170130101025. PMID 7827672. http://archpedi.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=7827672.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "Carbamazepine Toxicity". eMedicine. 2 February 2019. http://www.emedicine.com/emerg/topic77.htm.

- ↑ "Drug Metabolism". Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. 2006. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-07-142280-2.

- ↑ "Drug interactions with benzodiazepines". Handbook of Drug Interactions: a Clinical and Forensic Guide. Humana. 2004. pp. 3–88. ISBN 978-1-58829-211-7. https://archive.org/details/handbookofdrugin0000unse/page/3.

- ↑ "[Drug interactions with methadone]" (in fr). Presse Médicale 28 (25): 1381–4. September 1999. PMID 10506872.

- ↑ "Mechanisms of Action of Antiseizure Drugs and the Ketogenic Diet". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 6 (5): a022780. May 2016. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a022780. PMID 26801895.

- ↑ "Carbamazepine-induced release of serotonin from rat hippocampus in vitro". Epilepsia 39 (10): 1054–63. October 1998. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01290.x. PMID 9776325.

- ↑ "Carbamazepine increases extracellular serotonin concentration: lack of antagonism by tetrodotoxin or zero Ca2+". European Journal of Pharmacology 328 (2–3): 153–62. June 1997. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(97)83041-5. PMID 9218697.

- ↑ "Pharmacological discrimination between effects of carbamazepine on hippocampal basal, Ca(2+)- and K(+)-evoked serotonin release". British Journal of Pharmacology 133 (4): 557–67. June 2001. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0704104. PMID 11399673.

- ↑ "Trigeminal Neuralgia: an overview from pathophysiology to pharmacological treatments". Molecular Pain 16. January 2020. doi:10.1177/1744806920901890. PMID 31908187.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 "Carbamazepine". PubChem. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/2554.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 (in German) Austria-Codex. Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. 2021. Tegretol retard 400 mg-Filmtabletten.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 "Chapter 8: Carbamazepine". The History of Epileptic Therapy: An Account of How Medication was Developed.. History of Medicine Series.. CRC Press. 1993. ISBN 978-1-85070-391-4.

- ↑ "Über Derivate des Iminodibenzyls". Helvetica Chimica Acta 37 (2): 472–83. 1954. doi:10.1002/hlca.19540370211.

- ↑ "A history of investigation on the mood stabilizing effect of carbamazepine in Japan". Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 52 (1): 3–12. February 1998. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.1998.tb00966.x. PMID 9682927.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 "Human health risk assessment of pharmaceuticals and personal care products in plant tissue due to biosolids and manure amendments, and wastewater irrigation". Environment International 75: 223–33. February 2015. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2014.11.020. PMID 25486094.

- ↑ "Determination of polar organic micropollutants in surface and pore water by high-resolution sampling-direct injection-ultra high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry". Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts 20 (12): 1716–1727. December 2018. doi:10.1039/C8EM00390D. PMID 30350841.

- ↑ "Carbamazepine" (in en). https://www.drugs.com/international/carbamazepine.html.

Further reading

- "Effects of antimanic mood-stabilizing drugs on fetuses, neonates, and nursing infants". Southern Medical Journal 94 (3): 304–22. March 2001. doi:10.1097/00007611-200194030-00007. PMID 11284518. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/410736_4.

- "Carbamazepine Therapy and HLA Genotype". Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). 2015. Bookshelf ID: NBK321445. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK321445/.

External links

- "Carbamazepine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://druginfo.nlm.nih.gov/drugportal/name/carbamazepine.

- Carbamazepine. UK National Health Service

|