Chemistry:Cyproterone acetate

Template:Use vanc name-list-styleTemplate:Cs1 config

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Androcur, Androcur Depot, Cyprostat, Siterone, others |

| Other names | SH-80714; SH-714; NSC-81430; 1α,2α-Methylene-6-chloro-17α-hydroxy-δ6-progesterone acetate; 1α,2α-Methylene-6-chloro-17α-hydroxypregna-4,6-diene-3,20-dione acetate |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intramuscular injection |

| Drug class | Steroidal antiandrogen; Progestogen; Progestin; Progestogen ester; Antigonadotropin |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Oral: 68–100%[1][2] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (CYP3A4)[6][7] |

| Elimination half-life | Oral: 1.6–4.3 days[3][4][5] IM: 3–4.3 days[2][3][5] |

| Excretion | Feces: 70%[3] Urine: 30%[3] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C24H29ClO4 |

| Molar mass | 416.94 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 200 to 201 °C (392 to 394 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Cyproterone acetate (CPA), sold alone under the brand name Androcur or with ethinylestradiol under the brand names Diane or Diane-35 among others, is an antiandrogen and progestin medication used in the treatment of androgen-dependent conditions such as acne, excessive body hair growth, early puberty, and prostate cancer, as a component of feminizing hormone therapy for transgender women, and in birth control pills.[1][4][8][9][10] It is formulated and used both alone and in combination with an estrogen. CPA is taken by mouth one to three times per day.

Common side effects of high-dose CPA in men include gynecomastia (breast development) and feminization. In both men and women, possible side effects of CPA include low sex hormone levels, reversible infertility, sexual dysfunction, fatigue, depression, weight gain, and elevated liver enzymes. At very high doses in older individuals, significant cardiovascular complications can occur. Rare but serious adverse reactions of CPA include blood clots, liver damage and brain tumors. CPA can also cause adrenal insufficiency as a withdrawal effect if it is discontinued abruptly from a high dosage. CPA blocks the effects of androgens such as testosterone in the body, which it does by preventing them from interacting with their biological target, the androgen receptor (AR), and by reducing their production by the gonads, hence their concentrations in the body.[1][8][11] In addition, it has progesterone-like effects by activating the progesterone receptor (PR).[1][8] It can also produce weak cortisol-like effects at very high doses.[1]

CPA was discovered in 1961.[12] It was originally developed as a progestin.[12] In 1965, the antiandrogenic effects of CPA were discovered.[13] CPA was first marketed, as an antiandrogen, in 1973, and was the first antiandrogen to be introduced for medical use.[14] A few years later, in 1978, CPA was introduced as a progestin in a birth control pill.[15] It has been described as a "first-generation" progestin[16] and as the prototypical antiandrogen.[17] CPA is available widely throughout the world.[18][19] An exception is the United States , where it is not approved for use.[20][21]

Medical uses

CPA is used as a progestin and antiandrogen in hormonal birth control and in the treatment of androgen-dependent conditions.[8] Specifically, CPA is used in combined birth control pills, in the treatment of androgen-dependent skin and hair conditions such as acne, seborrhea, excessive hair growth, and scalp hair loss, high androgen levels, in transgender hormone therapy, to treat prostate cancer, to reduce sex drive in sex offenders or men with paraphilias or hypersexuality, to treat early puberty, and for other uses.[22] It is used both at low doses and at higher doses.[citation needed]

In the United States, where CPA is not available, other medications with antiandrogenic effects are used to treat androgen-dependent conditions instead.[23] Examples of such medications include gonadotropin-releasing hormone modulators (GnRH modulators) like leuprorelin and degarelix, nonsteroidal antiandrogens like flutamide and bicalutamide, the diuretic and steroidal antiandrogen spironolactone, the progestin medroxyprogesterone acetate, and the 5α-reductase inhibitors finasteride and dutasteride.[23] The steroidal antiandrogen and progestin chlormadinone acetate is used as an alternative to CPA in Japan , South Korea , and a few other countries.[citation needed]

Birth control

CPA is used with ethinylestradiol as a combined birth control pill to prevent pregnancy. This birth control combination has been available since 1978.[15] The formulation is taken once daily for 21 days, followed by a 7-day free interval.[24] CPA has also been available in combination with estradiol valerate (brand name Femilar) as a combined birth control pill in Finland since 1993.[25][26] High-dose CPA tablets have a contraceptive effect and can be used as a form of birth control, although they are not specifically licensed as such.[27]

Skin and hair conditions

Females

CPA is used as an antiandrogen to treat androgen-dependent skin and hair conditions such as acne, seborrhea, hirsutism (excessive hair growth), scalp hair loss, and hidradenitis suppurativa in women.[28][29][30][31][32][33][34] These conditions are worsened by the presence of androgens, and by suppressing androgen levels and blocking their actions, CPA improves the symptoms of these conditions. CPA is used to treat such conditions both at low doses as a birth control pill and on its own at higher doses.[28][29][30][31][35] A birth control pill containing low-dose CPA in combination with ethinylestradiol to treat acne has been found to result in overall improvement in 75 to 90% of women, with responses approaching 100% improvement.[36] High-dose CPA alone likewise has been found to improve symptoms of acne by 75 to 90% in women.[37] Discontinuation of CPA has been found to result in marked recurrence of symptoms in up to 70% of women.[38] CPA is one of the most commonly used medications in the treatment of hirsutism, hyperandrogenism, and polycystic ovary syndrome in women throughout the world.[39][40]

Higher dosages of CPA are used in combination with an estrogen specifically at doses of 25 to 100 mg/day cyclically in the treatment of hirsutism in women.[40][41][42] The efficacy of such dosages of CPA in the treatment of hirsutism in women appear to be similar to that of spironolactone, flutamide, and finasteride.[41][42][39][40] Randomized controlled trials have found that higher dosages of CPA (e.g., 20 mg/day or 100 mg/day) added cyclically to a birth control pill containing ethinylestradiol and 2 mg/day CPA were no more effective or only marginally more effective in the treatment of severe hirsutism in women than the birth control pill alone.[40][42][39][43][44][45] Maintenance therapy with lower doses of CPA, such as 25 mg/day, has been found to be effective in preventing relapse of symptoms of hirsutism.[38] CPA has typically been combined with ethinylestradiol, but it can alternatively be used in combination with hormone replacement therapy dosages of estradiol instead.[40] CPA at a dosage of 50 mg/day in combination with 100 μg/day transdermal estradiol patches has been found to be effective in the treatment of hirsutism similarly to the combination of CPA with ethinylestradiol.[42][46]

The efficacy of the combination of an estrogen and CPA in the treatment of hirsutism in women appears to be due to marked suppression of total and free androgen levels as well as additional blockade of the androgen receptor.[39][40][47]

Males

CPA has been found to be effective in the treatment of acne in males, with marked improvement in symptoms observed at dosages of 25, 50, and 100 mg/day in different studies.[48][49][50][51] It can also halt further progression of scalp hair loss in men.[52][53][54] Increased head hair and decreased body hair has been observed with CPA in men with scalp hair loss.[55][8] However, its side effects in men, such as demasculinization, gynecomastia, sexual dysfunction, bone density loss, and reversible infertility, make the use of CPA in males impractical in most cases.[52][53][49][50][56][57][58] In addition, lower dosages of CPA, such as 25 mg/day, have been found to be better-tolerated in men.[50] But such doses also show lower effectiveness in the treatment of acne in men.[48]

High androgen levels

CPA is used as an antiandrogen to treat high androgen levels and associated symptoms such as masculinization due to conditions like polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) in women.[29][34][59][60][61][62] It is almost always combined with an estrogen, such as ethinylestradiol, when it is used in the treatment of PCOS in women.[63]

Menopausal hormone therapy

CPA is used at low doses in menopausal hormone therapy in combination with an estrogen to provide endometrial protection and treat menopausal symptoms.[64][1][65][66] It is used in menopausal hormone therapy under the brand name Climen, which is a sequential preparation that contains 2 mg estradiol valerate and 1 mg CPA.[64][65][66] Climen was the first product for use in menopausal hormone therapy containing CPA to be marketed.[65] It is available in more than 40 countries.[64]

Transgender hormone therapy

CPA is widely used as an antiandrogen and progestogen in feminizing hormone therapy for transgender women.[67][68][69][70][71][72][73] It has been historically used orally at a dosage of 10 to 100 mg/day and by intramuscular injection at a dosage of 300 mg once every 4 weeks.[74][75] Due to the desire of transgender women for demasculinization, the side effects of CPA are more acceptable for transgender women than for cisgender men.[53]

Studies have found that 10, 25, 50, and 100 mg/day CPA in combination with estrogen all result in equivalent and full testosterone suppression in transgender women.[76][77][78][79][80] In light of risks of CPA such as fatigue, blood clots, benign brain tumors, and liver damage, the use of lower dosages of CPA may help to minimize such risks.[80] As a result, a CPA dosage of 10 mg/day and no greater is now recommended by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, Version 8 (SOC8).[76]

CPA has an advantage over spironolactone as an antiandrogen in transgender women, as the combination of estrogen and CPA consistently suppresses testosterone levels into the normal female range whereas estrogen with spironolactone does not.[81][82][83][84][85][86][87] Spironolactone is the most widely used antiandrogen in transgender women in the United States, whereas CPA is widely used in Europe and throughout the rest of the world.[82][76]

Aside from adult transgender females, CPA has also been used as a puberty blocker and hence as an antiandrogen and antiestrogen to suppress puberty in transgender youth, although GnRH modulators are primarily used and more effective for this purpose.[88][89][69][90][91]

Prostate cancer

CPA is used as an antiandrogen monotherapy and means of androgen deprivation therapy in the palliative treatment of prostate cancer in men.[4][92][93][94][95][96] It is used at very high doses by mouth or by intramuscular injection to treat this disease. Antiandrogens do not cure prostate cancer, but can significantly extend life in men with the disease.[97][98][92] CPA has similar effectiveness to GnRH modulators and surgical castration, high-dose estrogen therapy (e.g., with diethylstilbestrol), and high-dose nonsteroidal antiandrogen monotherapy (e.g., with bicalutamide), but has significantly inferior effectiveness to combined androgen blockade with a GnRH modulator and a nonsteroidal antiandrogen (e.g., with bicalutamide or enzalutamide).[92][98][99][100][101] In addition, the combination of CPA with a GnRH modulator or surgical castration has not been found to improve outcomes relative to a GnRH modulator or surgical castration alone, in contrast to nonsteroidal antiandrogens.[102] Due to its inferior effectiveness, tolerability, and safety, CPA is rarely used in the treatment of prostate cancer today, having largely been superseded by GnRH modulators and nonsteroidal antiandrogens.[103][104] CPA is the only steroidal antiandrogen that continues to be used in the treatment of prostate cancer.[98]

Dose-ranging studies of CPA for prostate cancer were not performed, and the optimal dosage of CPA for the treatment of the condition has not been established.[105][106] A dosage range of oral CPA of 100 to 300 mg/day is used in the treatment of prostate cancer, but generally 150 to 200 mg/day oral CPA is used.[107][108] Schröder (1993, 2002) reviewed the issue of CPA dosage and recommended a dosage of 200 to 300 mg/day for CPA as a monotherapy and a dosage of 100 to 200 mg/day for CPA in combined androgen blockade (that is, CPA in combination with surgical or medical castration).[109][94] However, the combination of CPA with castration for prostate cancer has been found to significantly decrease overall survival compared to castration alone.[110] Hence, the use of CPA as the antiandrogen component in combined androgen blockade would appear not to be advisable.[110] When used by intramuscular injection to treat prostate cancer, CPA is used at a dosage of 300 mg once a week.[58]

The combination of CPA with an estrogen such as ethinylestradiol sulfonate or low-dose diethylstilbestrol has been used as a form of combined androgen blockade and as an alternative to the combination of CPA with surgical or medical castration.[109][111][112][113][114]

Sexual deviance

CPA is used as an antiandrogen and form of chemical castration in the treatment of paraphilias and hypersexuality in men.[115][116][117][55][118][119] It is used to treat sex offenders.[citation needed] The medication is approved in more than 20 countries for this indication and is predominantly employed in Canada , Europe, and the Middle East.[120] CPA works by decreasing sex drive and sexual arousal and producing sexual dysfunction. CPA can also be used to reduce sex drive in individuals with inappropriate sexual behaviors, such as people with intellectual disability and dementia.[121][122] The medication is also useful for treating self-harmful sexual behavior, such as masochism.[123] CPA has comparable effectiveness to medroxyprogesterone acetate in suppressing sexual urges and function but appears to be less effective than GnRH modulators like leuprorelin and has more side effects.[116]

High-dose CPA significantly decreases sexual fantasies and sexual activity in 80 to 90% of men with paraphilias.[120] In addition, it has been found to decrease the rate of reoffending in sex offenders from 85% to 6%, with most of the reoffenses being committed by individuals who did not follow their CPA treatment prescription.[120] It has been reported that in 80% of cases, 100 mg/day CPA is adequate to achieve the desired reduction of sexuality, whereas in the remaining 20% of cases, 200 mg/day is sufficient.[124] When only a partial reduction in sexuality is desired, 50 mg/day CPA can be useful.[124] Reduced sexual desire and erectile function occurs with CPA by the end of the first week of treatment, and becomes maximal within three to four weeks.[124][58] The dosage range is 50 to 300 mg/day.[58][124]

Early puberty

CPA is used as an antiandrogen and antiestrogen to treat precocious puberty in boys and girls.[8][60][125] However, it is not fully satisfactory for this indication because it is not able to completely suppress puberty.[126] For this reason, CPA has mostly been superseded by GnRH agonists in the treatment of precocious puberty.[60] CPA is not satisfactory for gonadotropin-independent precocious puberty.[127] CPA has been used at dosages of 50 to 300 mg/m2 to treat precocious puberty.[58][8]

Other uses

CPA is useful in the treatment of hot flashes, for instance due to androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer.[99][128][129][130]

CPA is useful for suppressing the testosterone flare at the initiation of GnRH agonist therapy.[131][99][132][4][60][133][134][135][136] It has been used successfully both alone and in combination with estrogens such as diethylstilbestrol for this purpose.[131][137]

Available forms

CPA is available in the form of oral tablets alone (higher-dose; 10 mg, 50 mg, 100 mg) or in combination with ethinylestradiol or estradiol valerate (low-dose; 1 or 2 mg CPA) and in the form of ampoules for intramuscular injection (higher-dose; 100 mg/mL, 300 mg/3 mL; brand name Androcur Depot).[138][139][140][141][142]

The higher-dose formulations are used to treat prostate cancer and certain other androgen-related indications while the low-dose formulations which also have an estrogen are used as combined birth control pills and are used in menopausal hormone therapy for the treatment of menopausal symptoms.[141][143]

Contraindications

Contraindications of CPA include:[144][145][47]

- Hypersensitivity to CPA or any of the other components of the medication

- Pregnancy, lactation, and breastfeeding

- Puberty (except if being used to treat precocious puberty or delay puberty)

- Liver diseases and liver dysfunction

- Chronic kidney disease

- Dubin–Johnson syndrome and Rotor syndrome

- History of jaundice or persistent pruritus during pregnancy

- History of herpes during pregnancy

- Previous or existing liver tumors (only if not due to metastases from prostate cancer)

- Previous or existing meningioma, hyperprolactinemia, or prolactinoma

- Wasting syndromes (except in inoperable prostate cancer)

- Severe depression

- Previous or existing thromboembolic processes, as well as stroke and myocardial infarction

- Severe diabetes with vascular changes

- Sickle-cell anemia

When CPA is used in combination with an estrogen, contraindications for birth control pills should also be considered.[47]

Side effects

CPA is generally well-tolerated and has a mild side-effect profile regardless of dosage when it is used in combination with an estrogen in women.[146][147] Side effects of CPA in general include hypogonadism (low sex-hormone levels) and associated symptoms such as demasculinization, sexual dysfunction, infertility, and osteoporosis (fragile bones); breast changes such as breast tenderness, breast enlargement, and gynecomastia (breasts in men); emotional changes such as fatigue and depression; and other side effects such as vitamin B12 deficiency, weak glucocorticoid effects, and elevated liver enzymes.[47] Weight gain can occur with CPA when it is used at high doses.[148][44] Some of the side effects of CPA can be improved or fully prevented if it is combined with an estrogen to prevent estrogen deficiency.[63][36] Few quantitative data are available on many of the potential side effects of CPA.[149] Pooled tolerability data for CPA is not available in the literature.[150] Cyproterone is also known to suppress adrenocortical function.[151]

At very high doses in aged men with prostate cancer, CPA can cause cardiovascular side effects. Rarely, CPA can produce blood clots, liver toxicity (including hepatitis, liver failure, and liver cancer), excessively high prolactin levels, and certain benign brain tumors including meningiomas (tumors of the meninges) and prolactinomas (prolactin-secreting tumors of the pituitary gland). Upon discontinuation from high doses, CPA can produce adrenal insufficiency as a withdrawal effect.

Overdose

CPA is relatively safe in acute overdose.[145] It is used at very high doses of up to 300 mg/day by mouth and 700 mg per week by intramuscular injection.[145][152] For comparison, the dose of CPA used in birth control pills is 2 mg/day.[153] There have been no deaths associated with CPA overdose.[145] There are no specific antidotes for CPA overdose, and treatment should be symptom-based.[145] Gastric lavage can be used in the event of oral overdose within the last 2 to 3 hours.[145]

Interactions

Inhibitors and inducers of the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP3A4 may interact with CPA.[145] Examples of strong CYP3A4 inhibitors include ketoconazole, itraconazole, clotrimazole, and ritonavir, while examples of strong CYP3A4 inducers include rifampicin, rifampin, phenytoin, carbamazepine, phenobarbital, and St. John's wort.[145] Certain anticonvulsant medications can substantially reduce levels of CPA, by as much as 8-fold.[31]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

CPA has antiandrogenic activity,[1][154] progestogenic activity,[1][154] weak partial glucocorticoid activity,[155] weak steroidogenesis inhibitor activity,[156] and agonist activity at the pregnane X receptor.[157][158][159] It has no estrogenic or antimineralocorticoid activity.[1] In terms of potency, CPA is described as a highly potent progestogen, a moderately potent antiandrogen, and a weak glucocorticoid.[47][148][36] Due to its progestogenic activity, CPA has antigonadotropic effects, and is able to suppress fertility and sex-hormone levels in both males and females.[1][8][47]

Pharmacokinetics

CPA can be taken by mouth or by injection into muscle.[8] It has near-complete oral bioavailability, is highly and exclusively bound to albumin in terms of plasma protein binding, is metabolized in the liver by hydroxylation and conjugation, has 15β-hydroxycyproterone acetate (15β-OH-CPA) as a single major active metabolite, has a long elimination half-life of about 2 to 4 days regardless of route of administration, and is excreted in feces primarily and to a lesser extent in urine.[1][160][5]

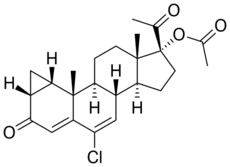

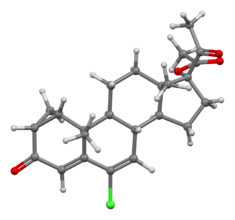

Chemistry

CPA, also known as 1α,2α-methylene-6-chloro-17α-acetoxy-δ6-progesterone or as 1α,2α-methylene-6-chloro-17α-hydroxypregna-4,6-diene-3,20-dione acetate, is a synthetic pregnane steroid and an acetylated derivative of 17α-hydroxyprogesterone.[161][162] It is structurally related to other 17α-hydroxyprogesterone derivatives such as chlormadinone acetate, hydroxyprogesterone caproate, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and megestrol acetate.[162]

Synthesis

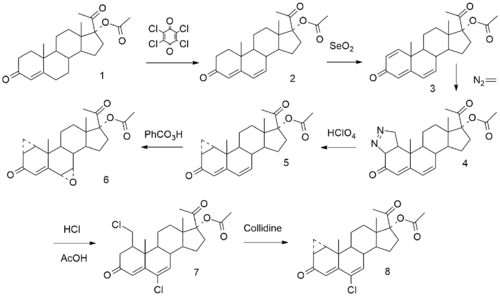

Chemical syntheses of CPA have been published.[139][163][164] The following is one such synthesis:[165][166]

The dehydrogenation of 17α-hydroxyprogesterone acetate [302-23-8] (1) with chloranil (tetrachloro-p-benzoquinone) gives a compound that has been called melengestrol acetate [425-51-4] (2). Dehydrogenation with selenium dioxide gives 17-acetoxy-1,4,6-pregnatriene-3,20-dione [2668-75-9] (3). Reacting this with diazomethane results in a 1,3-dipolar addition reaction at C1–C2 of the double bond of the steroid system, which forms a derivative of dihydropyrazole, CID:134990386 (4). This compound cleaves when reacted with perchloric acid,[167] releasing nitrogen molecules and forming a cyclopropane derivative, 6-deschloro cyproterone acetate [2701-50-0] (5). Selective oxidation of the C6=C7 olefin with benzoyl peroxide gives the epoxide, i.e. 6-deschloro-6,7-epoxy cyproterone [15423-97-9] (6). The penultimate step involves a reaction with hydrochloric acid in acetic acid, resulting in the formation of chlorine and its subsequent dehydration, and a simultaneous opening of the cyclopropane ring giving 1α-(chloromethyl) chlormadinone acetate [17183-98-1] (7). The heating of this in collidine reforms the cyclopropane ring, completing the synthesis of CPA (8).

History

CPA was first synthesized in 1961 by Rudolf Wiechert, a Schering employee, and together with Friedmund Neumann in Berlin, they filed for a patent for CPA as "progestational agent" in 1962.[12][168] The antiandrogenic activity of CPA was discovered serendipitously by Hamada, Neumann, and Karl Junkmann in 1963.[169][58] Along with the steroidal antiandrogens benorterone (17α-methyl-B-nortestosterone; SKF-7690), cyproterone, BOMT (Ro 7–2340), and trimethyltrienolone (R-2956) and the nonsteroidal antiandrogens flutamide and DIMP (Ro 7–8117), CPA was one of the first antiandrogens to be discovered and researched.[36][170][171][172]

CPA was initially developed as a progestogen for the prevention of threatened abortion.[58] As part of its development, it was assessed for androgenic activity to ensure that it would not produce teratogenic effects in female fetuses.[58] The drug was administered to pregnant rats and its effects on the rat fetuses were studied.[58] To the surprise of the researchers, all of the rat pups born appeared to be female.[58] After 20 female rat pups in a row had been counted, it was clear that this could not be a chance occurrence.[58] The rat pups were further evaluated and it was found that, in terms of karyotype, about 50% were actually males.[58] The male rat pups had been feminized, and this resultant finding constituted the discovery of the powerful antiandrogenic activity of CPA.[58] A year after patent approval in 1965, Neumann published additional evidence of CPA's antiandrogenic effect in rats; he reported an "organizational effect of CPA on the brain".[13] CPA started being used in animal experiments around the world to investigate how antiandrogens affected fetal sexual differentiation.[173]

The first clinical use of CPA in the treatment of sexual deviance and prostate cancer occurred in 1966.[9][174][175] It was first studied in the treatment of androgen-dependent skin and hair symptoms, specifically acne, hirsutism, seborrhea, and scalp hair loss, in 1969.[176] CPA was first approved for medical use in 1973 in Europe under the brand name Androcur.[163][177] In 1977, a formulation of CPA was introduced for use by intramuscular injection.[178] CPA was first marketed as a birth control pill in 1978 in combination with ethinylestradiol under the brand name Diane.[15] Following phase III clinical trials, CPA was approved for the treatment of prostate cancer in Germany in 1980.[178][179] CPA became available in Canada as Androcur in 1987, as Androcur Depot in 1990, and as Diane-35 in 1998.[180][181][182] Conversely, CPA was never introduced in any form in the United States .[20][23] This was reportedly due to concerns about breast tumors observed with high-dose pregnane progestogens in beagle dogs as well as concerns about potential teratogenicity in pregnant women.[183] Use of CPA in transgender women, an off-label indication, was reported as early as 1977.[184][185] The use of CPA in transgender women was well-established by the early 1990s.[186]

The history of CPA, including its discovery, development, and marketing, has been reviewed.[187][8]

Society and culture

Generic names

The English and generic name of CPA is cyproterone acetate and this is its USAN, BAN, and JAN.[18][19][188][189] The English and generic name of unacetylated cyproterone is cyproterone and this is its INN and BAN,[188][189][190] while cyprotérone is the DCF and French name and ciproterone is the DCIT and Italian name.[18][19] The name of unesterified cyproterone in Latin is cyproteronum, in German is cyproteron, and in Spanish is ciproterona.[18][19] These names of cyproterone correspond for CPA to acétate de cyprotérone in French, acetato de ciproterona in Spanish, ciproterone acetato in Italian, cyproteronacetat in German, cyproteronacetaat in Dutch. CPA is also known by the developmental code names SH-80714 and SH-714, while unacetylated cyproterone is known by the developmental code names SH-80881 and SH-881.[18][19][188][189]

Brand names

CPA is marketed under brand names including Androcur, Androcur Depot, Androcur-100, Androstat, Asoteron, Cyprone, Cyproplex, Cyprostat, Cysaxal, Imvel, and Siterone.[18][19] When CPA is formulated in combination with ethinylestradiol, it is also known as co-cyprindiol, and brand names for this formulation include Andro-Diane, Bella HEXAL 35, Chloe, Cypretil, Cypretyl, Cyproderm, Diane, Diane Mite, Diane-35, Dianette, Dixi 35, Drina, Elleacnelle, Estelle, Estelle-35, Ginette, Linface, Minerva, Vreya, and Zyrona.[18][19] CPA is also marketed in combination with estradiol valerate as Climen, Climene, Elamax, and Femilar.[18]

Availability

CPA is widely available throughout the world, and is marketed in almost every developed country,[191] with the notable major exceptions of the United States and Japan .[18][19][20][192][193] In almost all countries in which CPA is marketed, it is available both alone and in combination with an estrogen in birth control pills.[18][192][193] CPA is marketed widely in combination with both ethinylestradiol and estradiol valerate.[18][19][192][193] CPA-containing birth control pills are available in South Korea , but CPA as a standalone medication is not marketed in this country.[18][19][192][193] In Japan and South Korea, the closely related antiandrogen and progestin chlormadinone acetate, as well as other medications, are used instead of CPA.[194] Specific places in which CPA is marketed include the United Kingdom , elsewhere throughout Europe, Canada , Australia , New Zealand, South Africa , Latin America, and Asia.[18][19][192][193] CPA is not marketed in most of Africa and the Middle East.[18][19][192][193]

It has been said that the lack of availability of CPA in the United States explains why there are relatively few studies of it in the treatment of androgen-dependent conditions such as hyperandrogenism and hirsutism in women.[146]

Generation

Progestins in birth control pills are sometimes grouped by generation.[195][196] While the 19-nortestosterone progestins are consistently grouped into generations, the pregnane progestins that are or have been used in birth control pills are typically omitted from such classifications or are grouped simply as "miscellaneous" or "pregnanes".[195][196] In any case, CPA has been described as a "first-generation" progestin similarly to closely related progestins like chlormadinone acetate, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and megestrol acetate.[16][197]

Research

CPA has been studied and used in combination with low-dose diethylstilbestrol in the treatment of prostate cancer.[111][113][112] The combination results in suppression of testosterone levels into the castrate range, which normally cannot be achieved with CPA alone.[113] CPA has been studied as a form of androgen deprivation therapy for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia (enlarged prostate).[198][199][200] The medication has been studied in the treatment of breast cancer as well.[201][202]

CPA has been studied for use as a potential male hormonal contraceptive both alone and in combination with testosterone in men.[203][204] CPA was under development by Barr Pharmaceuticals in the 2000s for the treatment of hot flashes in prostate cancer patients in the United States .[205] It reached phase III clinical trials for this indication and had the tentative brand name CyPat but development was ultimately discontinued in 2008.[205] CPA is not satisfactorily effective as topical antiandrogen, for instance in the treatment of acne.[161] CPA has been used to treat estrogen hypersensitivity vulvovaginitis in women.[206]

CPA has been investigated for use in reducing aggression and self-injurious behavior via its antiandrogenic effects in conditions like autism spectrum disorders, dementias like Alzheimer's disease, and psychosis.[207][208][209][210] CPA may be effective in the treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD).[211][212][213][214] CPA has been studied in the treatment of cluster headaches in men.[215]

See also

- Estradiol valerate/cyproterone acetate

- Ethinylestradiol/cyproterone acetate

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 "Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration". Climacteric 8 (Suppl 1): 3–63. 2005. doi:10.1080/13697130500148875. PMID 16112947.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Pharmacokinetics of cyproterone acetate and its main metabolite 15 beta-hydroxy-cyproterone acetate in young healthy women". Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol 26 (11): 555–61. November 1988. PMID 2977383.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedWeber-2015 - ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "Cyproterone. A review of its pharmacology and therapeutic efficacy in prostate cancer". Drugs Aging 5 (1): 59–80. July 1994. doi:10.2165/00002512-199405010-00006. PMID 7919640.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 AAPL Newsletter. The Academy. 1998. http://courtpsychiatrist.com/pdf/pharmacological%20treatment%20sex%20offenders.pdf. "CPA is 100% bioavailable when taken orally with a half life of 38 hours. The injectable form reaches maximum plasma levels in 82 hours and has a half life of about 72 hours."

- ↑ Drugs in Palliative Care. OUP Oxford. 27 September 2012. pp. 137–138. ISBN 978-0-19-966039-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=LKrZINavapAC&pg=PA138.

- ↑ Pharmacology for Pharmacy and the Health Sciences: A Patient-centred Approach. OUP Oxford. 25 March 2010. pp. 632–. ISBN 978-0-19-955982-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=KVicAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA632.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 8.8 8.9 "The antiandrogen cyproterone acetate: discovery, chemistry, basic pharmacology, clinical use and tool in basic research". Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. 102 (1): 1–32. 1994. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1211261. PMID 8005205.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Pharmacology and potential use of cyproterone acetate". Horm. Metab. Res. 9 (1): 1–13. January 1977. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1093574. PMID 66176.

- ↑ "Pharmacology of antiandrogens". Journal of Steroid Biochemistry 25 (5B): 885–95. November 1986. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(86)90320-1. PMID 2949114.

- ↑ Berek & Novak's Gynecology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2007. p. 1085. ISBN 978-0-7817-6805-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=P3erI0J8tEQC&pg=PA1085.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 "Treatment of androgen excess in females: yesterday, today and tomorrow". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 11 (6): 411–33. December 1997. doi:10.3109/09513599709152569. PMID 9476091.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Permanent changes in gonadal function and sexual behaviour as a result of early feminization of male rats by treatment with an antiandrogenic steroid". Endokrinologie 50 (5): 209–225. 1966. PMID 5989926.

- ↑ Systemic Drug Treatment in Dermatology: A Handbook. CRC Press. 1 June 2002. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-84076-013-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=F1ZiAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA32.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 ACNE and ROSACEA. Springer Science & Business Media. 6 December 2012. pp. 662, 685. ISBN 978-3-642-59715-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=0cD-CAAAQBAJ&pg=PA685.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Progestins used in endocrine therapy and the implications for the biosynthesis and metabolism of endogenous steroid hormones". Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 441: 31–45. February 2017. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2016.09.004. PMID 27616670.

- ↑ Endocrinology: Adult and Pediatric E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. 25 February 2015. pp. 2293, 2464, 2479, 6225. ISBN 978-0-323-32195-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=xmLeBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA2293.

- ↑ 18.00 18.01 18.02 18.03 18.04 18.05 18.06 18.07 18.08 18.09 18.10 18.11 18.12 18.13 "Cyproterone". https://www.drugs.com/international/cyproterone.html.

- ↑ 19.00 19.01 19.02 19.03 19.04 19.05 19.06 19.07 19.08 19.09 19.10 19.11 Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. January 2000. pp. 289–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=5GpcTQD_L2oC&pg=PA289.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Surgical Management of the Transgender Patient. Elsevier Health Sciences. 22 September 2016. pp. 26–. ISBN 978-0-323-48408-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=eGkgDQAAQBAJ&pg=PP26.

- ↑ "Cancer Chemotherapy". Drug-Induced Liver Disease. Academic Press. 2013. pp. 541–567. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-387817-5.00030-3. ISBN 9780123878175.

- ↑ Hormonal Therapy for Male Sexual Dysfunction. John Wiley & Sons. 17 November 2011. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-119-96380-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=in_DuQFgcJMC&pg=PA104.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Incapacitation: Trends and New Perspectives. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.. 28 January 2013. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-4094-7151-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=OfGlANwlHAEC&pg=PT77.

- ↑ https://www.bayer.ca/omr/online/diane-35-pm-en.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ↑ "An overview of the development of combined oral contraceptives containing estradiol: focus on estradiol valerate/dienogest". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 28 (5): 400–8. May 2012. doi:10.3109/09513590.2012.662547. PMID 22468839.

- ↑ "Review of clinical experience with estradiol in combined oral contraceptives". Contraception 81 (1): 8–15. 2010. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2009.08.010. PMID 20004267.

- ↑ "Hormonal contraception in women at risk of vascular and metabolic disorders: guidelines of the French Society of Endocrinology". Ann. Endocrinol. (Paris) 73 (5): 469–87. November 2012. doi:10.1016/j.ando.2012.09.001. PMID 23078975.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "Cyproterone acetate for hirsutism". Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010 (4): CD001125. 2003. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001125. PMID 14583927.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 "The use of cyproterone acetate/ethinyl estradiol in hyperandrogenic skin symptoms - a review". Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 22 (3): 172–182. June 2017. doi:10.1080/13625187.2017.1317339. PMID 28447864.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "Oral contraceptives and cyproterone acetate in female acne treatment". Dermatology (Basel) 196 (1): 148–52. 1998. doi:10.1159/000017849. PMID 9557250.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 "Treatment of hirsutism and acne with cyproterone acetate". Clin Endocrinol Metab 15 (2): 373–89. May 1986. doi:10.1016/S0300-595X(86)80031-7. PMID 2941191.

- ↑ "Interventions for hidradenitis suppurativa". Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017 (10): CD010081. October 2015. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010081.pub2. PMID 26443004.

- ↑ "Female pattern hair loss". Alopecias - Practical Evaluation and Management. Current Problems in Dermatology. 47. 2015. 45–54. doi:10.1159/000369404. ISBN 978-3-318-02774-7.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "Managing cutaneous manifestations of hyperandrogenic disorders: the role of oral contraceptives". Treat Endocrinol 1 (6): 372–86. 2002. doi:10.2165/00024677-200201060-00003. PMID 15832490.

- ↑ "Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (7): CD004425. July 2012. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004425.pub6. PMID 22786490.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 "Current aspects of antiandrogen therapy in women". Curr. Pharm. Des. 5 (9): 707–23. September 1999. doi:10.2174/1381612805666230111201150. PMID 10495361. https://books.google.com/books?id=9rfNZL6oEO0C&pg=PA707.

- ↑ "Is hormonal treatment still an option in acne today?". Br. J. Dermatol. 172 (Suppl 1): 37–46. 2015. doi:10.1111/bjd.13681. PMID 25627824.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "Anti-androgens in gynaecological practice". Baillière's Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2 (3): 581–95. September 1988. doi:10.1016/S0950-3552(88)80045-2. PMID 2976627.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 "Medical treatment regimens of hirsutism". Reproductive Biomedicine Online 8 (5): 538–46. May 2004. doi:10.1016/S1472-6483(10)61100-5. PMID 15151716.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 40.4 40.5 "Hirsutism". Current Obstetrics & Gynaecology 15 (3): 174–182. 2005. doi:10.1016/j.curobgyn.2005.03.006. ISSN 0957-5847.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 "Hirsutism". Lancet 349 (9046): 191–5. January 1997. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07252-2. PMID 9111556.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 "Idiopathic hirsutism". Endocrine Reviews 21 (4): 347–62. August 2000. doi:10.1210/edrv.21.4.0401. PMID 10950156.

- ↑ "Unwanted body hair and its removal: a review". Dermatologic Surgery 25 (6): 431–9. June 1999. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.08130.x. PMID 10469088.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 "Clinical efficacy and safety of cyproterone acetate in severe hirsutism: results of a multicentered Canadian study". Fertility and Sterility 46 (6): 1015–20. December 1986. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(16)49873-0. PMID 2946604.

- ↑ "Cyproterone acetate for severe hirsutism: results of a double-blind dose-ranging study". Clinical Endocrinology 35 (1): 5–10. July 1991. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1991.tb03489.x. PMID 1832346.

- ↑ "Treatment of hirsutism by an association of oral cyproterone acetate and transdermal 17 beta-estradiol". Fertility and Sterility 55 (4): 742–5. April 1991. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(16)54240-X. PMID 1826278.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 47.4 47.5 "Antiandrogens: Clinical Aspects". Hair and Hair Diseases. Springer. 1990. pp. 827–886. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-74612-3_35. ISBN 978-3-642-74614-7.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 "Isotretinoin. A review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy in acne and other skin disorders". Drugs 28 (1): 6–37. July 1984. doi:10.2165/00003495-198428010-00002. PMID 6235105.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Chapter 18. Chemical Control of Androgen Action. Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry. 21. Academic Press. 1986. pp. 179–188. doi:10.1016/S0065-7743(08)61128-8. ISBN 9780120405213.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 "Cyproteronacetate in the management of severe acne in males". Archives of Dermatological Research 271 (2): 183–187. 1981. doi:10.1007/BF00412545. ISSN 0340-3696.

- ↑ "Response of male acne to antiandrogen therapy with cyproterone acetate". Dermatologica 173 (3): 139–42. 1986. doi:10.1159/000249236. PMID 2945742.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 "The Effect of Drugs on Hair". Pharmacology of the Skin II. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 87 / 2. Springer. 1989. pp. 495–508. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-74054-1_37. ISBN 978-3-642-74056-5.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 "Androgenetic alopecia and its treatment. A historical overview". Hair Transplantation, Third Edition. Taylor & Francis. 1 February 1995. pp. 1–33. ISBN 978-0-8247-9363-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=_KxsAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ "Dermatologic therapy: December, 1982, through November, 1983". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 11 (1): 25–52. July 1984. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(84)80163-2. PMID 6376557.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 "Cyproterone acetate in the treatment of sexual disorders: pharmacological base and clinical experience". Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. 98 (2): 71–80. 1991. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1211103. PMID 1838080.

- ↑ "Potential side effects of androgen deprivation treatment in sex offenders". The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 37 (1): 53–8. 2009. PMID 19297634.

- ↑ "Medical Management Options for Hair Loss". Aesthetic Medicine. Springer. 2012. pp. 529–535. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-20113-4_41. ISBN 978-3-642-20112-7.

- ↑ 58.00 58.01 58.02 58.03 58.04 58.05 58.06 58.07 58.08 58.09 58.10 58.11 58.12 "Pharmacology of Cyproterone Acetate — A Short Review". Antiandrogens in Prostate Cancer. ESO Monographs. 1996. pp. 31–44. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-45745-6_3. ISBN 978-3-642-45747-0.

- ↑ "Use of cyproterone acetate/ethinylestradiol in polycystic ovary syndrome: rationale and practical aspects". Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 22 (3): 183–190. June 2017. doi:10.1080/13625187.2017.1317735. PMID 28463030.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 "Experience with cyproterone acetate in the treatment of precocious puberty". J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 13 (Suppl 1): 805–10. July 2000. doi:10.1515/JPEM.2000.13.S1.805. PMID 10969925.

- ↑ "Hyperandrogenism in adolescent girls". Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. Endocrine Development. 22. 2012. 181–93. doi:10.1159/000326688. ISBN 978-3-8055-9336-6.

- ↑ "Pharmacological options for treatment of hyperandrogenic disorders". Mini Rev Med Chem 9 (9): 1113–26. August 2009. doi:10.2174/138955709788922692. PMID 19689407.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 "How actual is the treatment with antiandrogen alone in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome?". J. Endocrinol. Invest. 21 (9): 623–9. October 1998. doi:10.1007/BF03350788. PMID 9856417.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 "Clinical Experiences with a Combination of Estradiol Valerate and Cyproterone Acetate for Hormone Replacement". Women's Health and Menopause. Medical Science Symposia Series. 11. Springer. 1997. pp. 257–261. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-5560-1_38. ISBN 978-94-010-6343-2.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 "Androgens and antiandrogens". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 997 (1): 292–306. November 2003. doi:10.1196/annals.1290.033. PMID 14644837. Bibcode: 2003NYASA.997..292S.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 "The role of antiandrogens in hormone replacement therapy". Climacteric 3 (Suppl 2): 21–7. December 2000. PMID 11379383.

- ↑ "Long-term treatment of transsexuals with cross-sex hormones: extensive personal experience". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 93 (1): 19–25. January 2008. doi:10.1210/jc.2007-1809. PMID 17986639.

- ↑ "Endocrine Treatment of Gender-Dysphoric/Gender-Incongruent Persons: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 102 (11): 3869–3903. November 2017. doi:10.1210/jc.2017-01658. PMID 28945902.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 "Hormonal Treatment in Young People With Gender Dysphoria: A Systematic Review". Pediatrics 141 (4): e20173742. April 2018. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-3742. PMID 29514975.

- ↑ Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People (2nd ed.), University of California, San Francisco: Center of Excellence for Transgender Health, 17 June 2016, p. 28, http://transhealth.ucsf.edu/pdf/Transgender-PGACG-6-17-16.pdf

- ↑ Transsexual and Other Disorders of Gender Identity: A Practical Guide to Management. CRC Press. 29 September 2017. pp. 216–217, 221. ISBN 978-1-315-34513-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=P803DwAAQBAJ&pg=PT216.

- ↑ Principles of Transgender Medicine and Surgery. Routledge. 20 May 2016. pp. 169, 171, 216. ISBN 978-1-317-51460-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=LwszDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA169.

- ↑ Transgender Care: Recommended Guidelines, Practical Information, and Personal Accounts. Temple University Press. March 2001. pp. 66–. ISBN 978-1-56639-852-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=IlPX6E5glDEC&pg=PA66.

- ↑ "Hormonbehandlung bei Transgenderpatienten". Gynäkologische Endokrinologie 15 (1): 39–42. 2017. doi:10.1007/s10304-016-0116-9. ISSN 1610-2894.

- ↑ "Behandlungsgrundsätze bei Transsexualität". Gynäkologische Endokrinologie 7 (3): 153–160. 2009. doi:10.1007/s10304-009-0314-9. ISSN 1610-2894.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 76.2 "Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, Version 8". International Journal of Transgender Health 23 (Suppl 1): S1–S259. 19 August 2022. doi:10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644. PMID 36238954.

- ↑ "Toward a Lowest Effective Dose of Cyproterone Acetate in Trans Women: Results From the ENIGI Study". J Clin Endocrinol Metab 106 (10): e3936–e3945. September 2021. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgab427. PMID 34125226.

- ↑ "Low-Dose Cyproterone Acetate Treatment for Transgender Women". J Sex Med 18 (7): 1292–1298. July 2021. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.04.008. PMID 34176757.

- ↑ "Safety and rapid efficacy of guideline-based gender affirming hormone therapy: an analysis of 388 individuals diagnosed with gender dysphoria". European Journal of Endocrinology 182 (2): 149–156. November 2019. doi:10.1530/EJE-19-0463. PMID 31751300.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 "Is a lower dose of cyproterone acetate as effective at testosterone suppression in transgender women as higher doses?". International Journal of Transgenderism 18 (2): 123–128. 2017. doi:10.1080/15532739.2017.1290566. ISSN 1553-2739.

- ↑ "Gender-affirming hormonal therapy for transgender and gender-diverse people-A narrative review". Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 86: 102296. February 2023. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2022.102296. PMID 36596713.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 "MANAGEMENT OF ENDOCRINE DISEASE: Optimal feminizing hormone treatment in transgender people". Eur J Endocrinol 185 (2): R49–R63. June 2021. doi:10.1530/EJE-21-0059. PMID 34081614.

- ↑ "A systematic review of antiandrogens and feminization in transgender women". Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 94 (5): 743–752. May 2021. doi:10.1111/cen.14329. PMID 32926454.

- ↑ "Feminizing gender-affirming hormone therapy for the transgender and gender diverse population: An overview of treatment modality, monitoring, and risks". Neurourol Urodyn 42 (5): 903–920. November 2022. doi:10.1002/nau.25097. PMID 36403287.

- ↑ "Anti-Androgenic Effects Comparison Between Cyproterone Acetate and Spironolactone in Transgender Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial". J Sex Med 18 (7): 1299–1307. July 2021. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.05.003. PMID 34274044.

- ↑ "Differential Endocrine and Metabolic Effects of Testosterone Suppressive Agents in Transgender Women". Endocr Pract 26 (8): 883–890. August 2020. doi:10.4158/EP-2020-0032. PMID 33471679.

- ↑ "Cyproterone acetate or spironolactone in lowering testosterone concentrations for transgender individuals receiving oestradiol therapy". Endocr Connect 8 (7): 935–940. July 2019. doi:10.1530/EC-19-0272. PMID 31234145.

- ↑ "Transgender medicine - puberty suppression". Reviews in Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders 19 (3): 221–225. September 2018. doi:10.1007/s11154-018-9457-0. PMID 30112593.

- ↑ "Approach to the patient: transgender youth: endocrine considerations". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 99 (12): 4379–89. December 2014. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-1919. PMID 25140398.

- ↑ "Puberty suppression in transgender children and adolescents". The Lancet. Diabetes & Endocrinology 5 (10): 816–826. October 2017. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30099-2. PMID 28546095.

- ↑ "Consecutive Cyproterone Acetate and Estradiol Treatment in Late-Pubertal Transgender Female Adolescents". The Journal of Sexual Medicine 14 (5): 747–757. May 2017. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.03.251. PMID 28499525.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 92.2 "Cyproterone acetate in the therapy of prostate carcinoma". Archivio Italiano di Urologia, Andrologia 77 (3): 157–63. June 2005. PMID 16372511.

- ↑ "Cyproterone Acetate — Results of Clinical Trials and Indications for Use in Human Prostate Cancer". Antiandrogens in Prostate Cancer. ESO Monographs. 1996. pp. 45–51. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-45745-6_4. ISBN 978-3-642-45747-0.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 "Cyproterone acetate--mechanism of action and clinical effectiveness in prostate cancer treatment". Cancer 72 (12 Suppl): 3810–5. December 1993. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19931215)72:12+<3810::AID-CNCR2820721710>3.0.CO;2-O. PMID 8252496.

- ↑ "The position of cyproterone acetate (CPA), a steroidal anti-androgen, in the treatment of prostate cancer". The Prostate. Supplement 4: 91–5. 1992. doi:10.1002/pros.2990210514. PMID 1533452.

- ↑ "Use of cyproterone acetate in prostate cancer". The Urologic Clinics of North America 18 (1): 111–22. February 1991. doi:10.1016/S0094-0143(21)01398-7. PMID 1825143.

- ↑ Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2008. pp. 1288–. ISBN 978-0-7817-6879-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=R0W1ErpsQpkC&pg=PA1288.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 98.2 "Single-therapy androgen suppression in men with advanced prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine 132 (7): 566–77. April 2000. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-132-7-200004040-00009. PMID 10744594.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 99.2 Prostate Cancer: Science and Clinical Practice. Elsevier Science. 29 September 2015. pp. 516–521, 534–540. ISBN 978-0-12-800592-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=292cBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA530.

- ↑ "Androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: current status and future prospects". The Prostate 61 (4): 332–53. December 2004. doi:10.1002/pros.20115. PMID 15389811.

- ↑ "Antiandrogens in the treatment of prostate cancer". European Urology 51 (2): 306–13; discussion 314. February 2007. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2006.08.043. PMID 17007995.

- ↑ "Androgen receptor antagonists (antiandrogens): structure-activity relationships". Current Medicinal Chemistry 7 (2): 211–47. February 2000. doi:10.2174/0929867003375371. PMID 10637363. "When compared to flutamide, [cyproterone acetate] has significant intrinsic androgenic and estrogenic activities. [...] The effects of flutamide and the steroidal derivatives, cyproterone acetate, chlormadinone acetate, megestrol acetate and medroxyprogesterone acetate were compared in vivo in female nude mice bearing androgen-sensitive Shionogi tumors. All steroidal compounds stimulated tumor growth while flutamide had no stimulatory effect [51]. Thus, CPA due to its intrinsic properties stimulates androgen-sensitive parameters and cancer growth. Cyproterone acetate added to castration has never been shown in any controlled study to prolong disease-free survival or overall survival in prostate cancer when compared with castration alone [152-155].".

- ↑ "Management of advanced prostate cancer". Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira 54 (2): 178–82. 2008. doi:10.1590/S0104-42302008000200025. PMID 18506331. http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ramb/v54n2/a25v54n2.pdf.

- ↑ Cancer Chemotherapy and Biotherapy: Principles and Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 8 November 2010. pp. 679–680. ISBN 978-1-60547-431-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=WL4arNFsQa8C&pg=PA680. "From a structural standpoint, antiandrogens are classified as steroidal, including cyproterone [acetate] (Androcur) and megestrol [acetate], or nonsteroidal, including flutamide (Eulexin, others), bicalutamide (Casodex), and nilutamide (Nilandron). The steroidal antiandrogens are rarely used."

- ↑ Systemic Treatment of Prostate Cancer. OUP Oxford. 11 February 2010. pp. 44–. ISBN 978-0-19-956142-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=MR-vVpipynUC&pg=PT44.

- ↑ "The role of antiandrogen monotherapy in the treatment of prostate cancer". BJU International 91 (5): 455–61. March 2003. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410X.2003.04026.x. PMID 12603397.

- ↑ "Maximum androgen blockade in advanced prostate cancer: an overview of the randomised trials". The Lancet 355 (9214): 1491–1498. 2000. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02163-2. ISSN 0140-6736.

- ↑ Antiandrogens in Prostate Cancer: A Key to Tailored Endocrine Treatment. Springer Science & Business Media. 6 December 2012. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-3-642-45745-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=jqZDBQAAQBAJ&pg=PT70.

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 "Steroidal Antiandrogens". Hormone Therapy in Breast and Prostate Cancer. Cancer Drug Discovery and Development. Humana Press. 2009. pp. 325–346. doi:10.1007/978-1-59259-152-7_15. ISBN 978-1-60761-471-5. https://archive.org/details/hormonetherapybr00crai.

- ↑ 110.0 110.1 "Combined androgen blockade in advanced prostate cancer: looking back to move forward". Clinical Genitourinary Cancer 5 (6): 371–8. September 2007. doi:10.3816/CGC.2007.n.019. PMID 17956709.

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 "Estrogens in the treatment of prostate cancer". The Journal of Urology 154 (6): 1991–1998. December 1995. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)66670-9. PMID 7500443.

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 "Low-dose cyproterone acetate plus mini-dose diethylstilbestrol--a protocol for reversible medical castration". Urology 47 (6): 882–884. June 1996. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(96)00048-9. PMID 8677581.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 113.2 "The combination of cyproterone acetate and low dose diethylstilbestrol in the treatment of advanced prostatic carcinoma". The Journal of Urology 140 (6): 1460–1465. December 1988. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(17)42073-8. PMID 2973529.

- ↑ Prostatakarzinom — urologische und strahlentherapeutische Aspekte: urologische und strahlentherapeutische Aspekte. Springer-Verlag. 7 March 2013. pp. 99–. ISBN 978-3-642-60064-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=wdTLBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA99.

- ↑ "Pharmacological interventions for those who have sexually offended or are at risk of offending". Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015 (2): CD007989. February 2015. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007989.pub2. PMID 25692326.

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 "Androgen deprivation therapy (castration therapy) and pedophilia: What's new". Arch Ital Urol Androl 87 (3): 222–6. September 2015. doi:10.4081/aiua.2015.3.222. PMID 26428645.

- ↑ "Protocols for the use of cyproterone, medroxyprogesterone, and leuprolide in the treatment of paraphilia". Can J Psychiatry 45 (6): 559–63. August 2000. doi:10.1177/070674370004500608. PMID 10986575.

- ↑ "Therapeutic sex drive reduction". Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 287: 5–38. 1980. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1980.tb10433.x. PMID 7006321.

- ↑ "Pharmacology of sexually compulsive behavior". Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 31 (4): 671–9. December 2008. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2008.06.002. PMID 18996306.

- ↑ 120.0 120.1 120.2 "Pharmacologic treatment of paraphilias". Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 37 (2): 173–81. June 2014. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2014.03.002. PMID 24877704.

- ↑ "Inappropriate sexual behaviors in cognitively impaired older individuals". Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 6 (5): 269–88. December 2008. doi:10.1016/j.amjopharm.2008.12.004. PMID 19161930.

- ↑ "Antilibidinal drugs and mental retardation: a review". Med Sci Law 29 (2): 136–46. April 1989. doi:10.1177/002580248902900209. PMID 2526280.

- ↑ "Self-harmful sexual behavior". Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 8 (2): 323–37. June 1985. doi:10.1016/s0193-953x(18)30698-1. PMID 3895195.

- ↑ 124.0 124.1 124.2 124.3 "Antiandrogens in the treatment of sexual deviations of men". J. Steroid Biochem. 6 (6): 821–6. June 1975. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(75)90310-6. PMID 1177426.

- ↑ "Update on the etiology, diagnosis and therapeutic management of sexual precocity". Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol 52 (1): 18–31. February 2008. doi:10.1590/S0004-27302008000100005. PMID 18345393.

- ↑ Advances in Pediatrics. JP Medical Ltd. 31 August 2012. pp. 1202–. ISBN 978-93-5025-777-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=I2FHFyCaDeIC&pg=PA1202.

- ↑ "Gonadotropin-independent precocious puberty". Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 20 (1): 191–210. March 1991. doi:10.1016/s0889-8529(18)30288-3. PMID 1903104.

- ↑ "Managing hot flushes in men after prostate cancer--a systematic review". Maturitas 65 (1): 15–22. January 2010. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.10.017. PMID 19962840.

- ↑ "Incidence and management of hot flashes in prostate cancer". J Support Oncol 1 (4): 263–6, 269–70, 272–3; discussion 267–8, 271–2. 2003. PMID 15334868.

- ↑ "Hot flushes: mechanism and prevention". Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 359: 131–40; discussion 141–53. 1990. PMID 2149457.

- ↑ 131.0 131.1 "Flare Associated with LHRH-Agonist Therapy". Rev Urol 3 (Suppl 3): S10–4. 2001. PMID 16986003.

- ↑ Textbook of Prostate Cancer: Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment: Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment. CRC Press. 1 March 1999. pp. 308–. ISBN 978-1-85317-422-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=GreZlojD-tYC&pg=PA308.

- ↑ "Bicalutamide vs cyproterone acetate in preventing flare with LHRH analogue therapy for prostate cancer—a pilot study". Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases 8 (1): 91–4. 2005. doi:10.1038/sj.pcan.4500784. PMID 15711607.

- ↑ "Influence of different types of antiandrogens on luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone analogue-induced testosterone surge in patients with metastatic carcinoma of the prostate". J. Urol. 144 (4): 934–41. October 1990. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(17)39625-8. PMID 2144596.

- ↑ "Cyproterone acetate lead-in prevents initial rise of serum testosterone induced by luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone analogs in the treatment of metastatic carcinoma of the prostate". Eur. Urol. 12 (6): 400–2. 1986. doi:10.1159/000472667. PMID 2949980.

- ↑ "Long-term results of an LH-RH agonist monotherapy in patients with carcinoma of the prostate and reflections on the so-called total androgen blockade with pre-medicated cyproterone acetate". Endocrine Management of Prostatic Cancer. De Gruyter. 1988. pp. 127–137. doi:10.1515/9783110853674-014. ISBN 9783110853674.

- ↑ "Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists in prostate cancer. Elimination of flare reaction by pretreatment with cyproterone acetate and low-dose diethylstilbestrol". Cancer 72 (5): 1685–91. September 1993. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19930901)72:5<1685::AID-CNCR2820720532>3.0.CO;2-3. PMID 7688656.

- ↑ "Hirsutismus – Medikamentöse Therapie Gemeinsame Stellungnahme der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Gynäkologische Endokrinologie und Fortpflanzungsmedizin e.V. und des Berufsverbands der Frauenärzte e.V." (in de). Journal für Reproduktionsmedizin und Endokrinologie 12 (3): 102–149. 2015. ISSN 1810-2107. https://www.kup.at/journals/summary/12989.html.

- ↑ 139.0 139.1 Pharmaceutical Substances: Syntheses, Patents and Applications of the most relevant APIs (5th ed.). Thieme. 14 May 2014. pp. 351–352. ISBN 978-3-13-179275-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=4lCGAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA351.

- ↑ European Drug Index: European Drug Registrations, Fourth Edition. CRC Press. 19 June 1998. pp. 79–. ISBN 978-3-7692-2114-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=2HBPHmclMWIC&pg=PA79.

- ↑ 141.0 141.1 Dermatology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. 8 June 2012. pp. 557–. ISBN 978-0-7020-5182-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=A78BaiEKnzIC&pg=PA557.

- ↑ Therapielexikon Dermatologie und Allergologie. Springer-Verlag. 2 July 2013. pp. 27–. ISBN 978-3-662-10498-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=f-WzBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA27.

- ↑ Current Therapy in Adult Medicine. Mosby. 1997. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-8151-5480-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=XqBLAQAAIAAJ.

- ↑ "Androcur Label". http://www.bayerresources.com.au/resources/uploads/PI/file9701.pdf.

- ↑ 145.0 145.1 145.2 145.3 145.4 145.5 145.6 145.7 "Mylan-Cyproterone Label". https://pdf.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00011374.PDF.

- ↑ 146.0 146.1 "Anti-androgen treatments". Ann. Endocrinol. (Paris) 71 (1): 19–24. February 2010. doi:10.1016/j.ando.2009.12.001. PMID 20096826.

- ↑ "Anti-androgen therapy in dermatology: a review". Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 4 (4): 501–7. December 1979. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.1979.tb01648.x. PMID 394887.

- ↑ 148.0 148.1 "Antiandrogen treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome". Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 28 (2): 409–21. June 1999. doi:10.1016/S0889-8529(05)70077-3. PMID 10352926.

- ↑ "Drug treatment of paraphilic and nonparaphilic sexual disorders". Clin Ther 31 (1): 1–31. January 2009. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.01.009. PMID 19243704. "No quantitative data on these adverse events are available, even in the product prescribing information and data sheets.".

- ↑ "Antiandrogens: a summary review of pharmacodynamic properties and tolerability in prostate cancer therapy". Arch Ital Urol Androl 71 (5): 293–302. December 1999. PMID 10673793.

- ↑ Mylan-Cypersterone Monograph at 4. https://pdf.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00011374.PDF

- ↑ Sex Offenders: Identification, Risk Assessment, Treatment, and Legal Issues. Oxford University Press, USA. 11 February 2009. pp. 197–. ISBN 978-0-19-517704-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=df0RDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA197.

- ↑ Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2011. pp. 1091–. ISBN 978-0-7817-7968-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ll73ZsBKLkwC&pg=PA1091.

- ↑ 154.0 154.1 Drug Management of Prostate Cancer. Springer. 14 September 2010. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-60327-829-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=4KDrjeWA5-UC&pg=PA71.

- ↑ "Glucocorticoid receptor antagonism by cyproterone acetate and RU486". Molecular Pharmacology 63 (5): 1012–20. May 2003. doi:10.1124/mol.63.5.1012. PMID 12695529.

- ↑ "Inhibition of rat testicular 17 alpha-hydroxylase and 17,20-lyase activities by anti-androgens (flutamide, hydroxyflutamide, RU23908, cyproterone acetate) in vitro". Journal of Steroid Biochemistry 28 (1): 43–7. July 1987. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(87)90122-1. PMID 2956461.

- ↑ Evaluation of Drug Candidates for Preclinical Development: Pharmacokinetics, Metabolism, Pharmaceutics, and Toxicology. John Wiley & Sons. 6 January 2010. pp. 92–. ISBN 978-0-470-57488-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=2TsQKxRdRVEC&pg=PA92.

- ↑ "The human orphan nuclear receptor PXR is activated by compounds that regulate CYP3A4 gene expression and cause drug interactions". The Journal of Clinical Investigation 102 (5): 1016–23. September 1998. doi:10.1172/JCI3703. PMID 9727070.

- ↑ "Functional interactions between P-glycoprotein and CYP3A in drug metabolism". Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology 1 (4): 641–54. December 2005. doi:10.1517/17425255.1.4.641. PMID 16863430.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedpmid14670641 - ↑ 161.0 161.1 "Clinical Uses of Antiandrogens". Androgens II and Antiandrogens / Androgene II und Antiandrogene. Handbuch der experimentellen Pharmakologie/Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Springer. 1974. pp. 485–542. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-80859-3_7. ISBN 978-3-642-80861-6.

- ↑ 162.0 162.1 Office Gynecology: Advanced Management Concepts. Springer Science & Business Media. 6 December 2012. pp. 150–. ISBN 978-1-4612-4340-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=dgnpBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA150.

- ↑ 163.0 163.1 William Andrew Publishing (22 October 2013). Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia. Elsevier. pp. 1182–1183. ISBN 978-0-8155-1856-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=_J2ti4EkYpkC&pg=PA1182.

- ↑ Buddhasukh D, Maier R, Manosroi A, Manosroi J, Sripalakit P, Werner R, "Further syntheses of cyproterone acetate", EP patent 1359154A1, published 5 November 2003

- ↑ 165.0 165.1 "Verfahren zur Herstellung von 1, 2alpha-Methylen-delta-17alpha-hydroxy-progesteronen". https://patents.google.com/patent/DE1189991B.

- ↑ 166.0 166.1 "6-chloro-1, 2alpha-methylene-delta6-17alpha-hydroxyprogesterone compounds and compositions". https://patents.google.com/patent/US3234093A.

- ↑ Rudolf Wiechert, U.S. Patent 3,127,396 (1964).

- ↑ U.S. Patent 3,234,093

- ↑ "Intrauterine Antimaskuline Beeinflussung von Rattenfeten Durch ein Stark Gestagen Wirksames Steroid" (in de). Acta Endocrinologica 44 (3): 380–8. November 1963. doi:10.1530/acta.0.0440380. PMID 14071315.

- ↑ Male Reproductive Function and Semen: Themes and Trends in Physiology, Biochemistry and Investigative Andrology. Springer Science & Business Media. 6 December 2012. pp. 352–. ISBN 978-1-4471-1300-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=cezjBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA352.

- ↑ Hormones. Elsevier Science. 28 June 2014. pp. 508–. ISBN 978-1-4832-5810-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=AORRAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA508.

- ↑ The Mechanism of Action of Androgens. Springer Science & Business Media. 6 December 2012. pp. 53–. ISBN 978-3-642-88429-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=rrDoCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA53.

- ↑ "Use of androgen antagonists and antiandrogens in studies on sex differentiation". Gynecol Invest 2 (1): 180–201. 1971. doi:10.1159/000301861. PMID 4949979.

- ↑ "The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of paraphilias". The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry 11 (4): 604–55. June 2010. doi:10.3109/15622971003671628. PMID 20459370.

- ↑ "Clinical applications of antiandrogens". Journal of Steroid Biochemistry 31 (4B): 719–29. October 1988. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(88)90023-4. PMID 2462132.

- ↑ "[Management of hirsutism using cyproterone acetate]" (in de). Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift 94 (16): 829–34. April 1969. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1111126. PMID 4304873.

- ↑ Cancer and its Management. Wiley. 3 October 2014. pp. 379–. ISBN 978-1-118-46871-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=CXjDBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA379.

- ↑ 178.0 178.1 "Clinical experience with cyproterone acetate for palliation of inoperable prostate cancer". Prostate Cancer. Williams & Wilkins. 1 December 1982. pp. 305–319. ISBN 978-0-683-04354-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=4HNrAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ "Treatment of advanced prostatic cancer with parenteral cyproterone acetate: a phase III randomised trial". British Journal of Urology 52 (3): 208–15. June 1980. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.1980.tb02961.x. PMID 7000222.

- ↑ "Androcur". Drug Product Database Online Query. Health Canada. 25 April 2012. https://health-products.canada.ca/dpd-bdpp/info.do?lang=en&code=7394#fn1.

- ↑ "Androcur Depot". Drug Product Database Online Query. Health Canada. 25 April 2012. https://health-products.canada.ca/dpd-bdpp/info.do?lang=en&code=11880#fn1-rf.

- ↑ "DIANE-35". Drug Product Database Online Query. Health Canada. 25 April 2012. https://health-products.canada.ca/dpd-bdpp/info.do?lang=en&code=53444.

- ↑ Principles and Practice of Endocrinology and Metabolism. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2001. pp. 1004–. ISBN 978-0-7817-1750-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=FVfzRvaucq8C&pg=PA1004.

- ↑ "Of Homosexuality: The Current State of Knowledge". Journal of Christian Education os-20 (2): 58–82. 1977. doi:10.1177/002196577702000204. ISSN 0021-9657.

- ↑ "Transsexualismus: Erfahrungen mit der operativen Korrektur bei männlichen Transsexuellen". Aktuelle Urologie 11 (2): 67–77. 1980. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1062961. ISSN 0001-7868.

- ↑ "Hormone Treatment in Transsexuals". Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality 5 (4): 39–54. 1993. doi:10.1300/J056v05n04_03. ISSN 0890-7064.

- ↑ "Das Antiandrogen Cyproteronacetat Seine Geschichte von der Entdeckung bis zur Marktreife" (in de). Pharmazie in unserer Zeit 17 (2): 33–50. March 1988. doi:10.1002/pauz.19880170202. ISSN 0048-3664. PMID 2967500.

- ↑ 188.0 188.1 188.2 The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. 14 November 2014. pp. 339–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=0vXTBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA339.

- ↑ 189.0 189.1 189.2 Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. 6 December 2012. pp. 89–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=tsjrCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA89.

- ↑ Dictionary of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Walter de Gruyter. 1 January 1988. pp. 61–. ISBN 978-3-11-085727-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=EQlvzV9V7xIC&pg=PA61.

- ↑ Acne: Causes and Practical Management. John Wiley & Sons. 27 January 2015. pp. 142–. ISBN 978-1-118-23277-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=Z1yFBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA142.

- ↑ 192.0 192.1 192.2 192.3 192.4 192.5 http://www.micromedexsolutions.com/micromedex2/[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ 193.0 193.1 193.2 193.3 193.4 193.5 Sweetman, Sean C., ed (2009). "Sex hormones and their modulators". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference (36th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. p. 2082. ISBN 978-0-85369-840-1. https://www.medicinescomplete.com/mc/martindale/2009/9034-b.htm.

- ↑ Prostate Cancer: Science and Clinical Practice. Academic Press. 11 July 2003. pp. 437–. ISBN 978-0-08-049789-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=EIXDBJj6H4wC&pg=PA437.

- ↑ 195.0 195.1 Contraceptive Choices and Realities: Proceedings of the 5th Congress of the European Society of Contraception. CRC Press. 15 February 2000. pp. 73–. ISBN 978-1-85070-067-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=-FliV0TxtEEC&pg=PA73.

- ↑ 196.0 196.1 IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; World Health Organization; International Agency for Research on Cancer (2007). Combined Estrogen-progestogen Contraceptives and Combined Estrogen-progestogen Menopausal Therapy. World Health Organization. pp. 44,437. ISBN 978-92-832-1291-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=aGDU5xibtNgC&pg=PA437.

- ↑ Obstetrics, Gynecology & Infertility: Handbook for Clinicians. Scrub Hill Press, Inc.. 2007. pp. 228–. ISBN 978-0-9645467-7-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=2JLC6yiA7fcC&pg=PA228.

- ↑ "Endocrine treatment of benign prostatic hypertrophy: current concepts". Urology 37 (1): 1–16. January 1991. doi:10.1016/0090-4295(91)80069-j. PMID 1702565.

- ↑ "[Androgen deprivation in benign prostatic hypertrophy]" (in fr). Journal d'Urologie 99 (6): 296–298. 1993. PMID 7516371.

- ↑ "[Pharmacological combinations in the treatment of benign prostatic hypertrophy]" (in fr). Journal d'Urologie 99 (6): 316–320. 1993. PMID 7516378.

- ↑ "Hormonal therapy of breast cancer". Cancer Treatment Reviews 24 (3): 221–240. June 1998. doi:10.1016/S0305-7372(98)90051-2. PMID 9767736.

- ↑ "Clinical and endocrine effects of cyproterone acetate in postmenopausal patients with advanced breast cancer". European Journal of Cancer & Clinical Oncology 24 (3): 417–421. March 1988. doi:10.1016/S0277-5379(98)90011-6. PMID 2968261.

- ↑ "Clinical trials in male hormonal contraception". Contraception 82 (5): 457–70. November 2010. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2010.03.020. PMID 20933120. http://www.kup.at/kup/pdf/10172.pdf.

- ↑ "The essential role of testosterone in hormonal male contraception". Testosterone. Cambridge University Press. 2012. pp. 470–493. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139003353.023. ISBN 9781139003353.

- ↑ 205.0 205.1 "Cyproterone acetate - Barr Laboratories - AdisInsight". http://adisinsight.springer.com/drugs/800015250.

- ↑ "Cyproterone acetate in the treatment of oestrogen hypersensitivity vulvovaginitis". The Australasian Journal of Dermatology 59 (1): 52–54. February 2018. doi:10.1111/ajd.12657. PMID 28718897.

- ↑ "An evaluation of the role and treatment of elevated male hormones in autism spectrum disorders". Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 72 (1): 1–17. 2012. doi:10.55782/ane-2012-1876. PMID 22508080.

- ↑ "Cyproterone to treat aggressivity in dementia: a clinical case and systematic review". J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford) 25 (1): 141–5. 2011. doi:10.1177/0269881109353460. PMID 19942637.

- ↑ "Aggression in humans: what is its biological foundation?". Neurosci Biobehav Rev 17 (4): 405–25. 1993. doi:10.1016/S0149-7634(05)80117-4. PMID 8309650.

- ↑ "A possible antiaggressive effect of cyproterone acetate". Br J Psychiatry 159 (2): 298–9. August 1991. doi:10.1192/bjp.159.2.298b. PMID 1837749.

- ↑ "Anti-androgen drugs in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic review". Curr Med Chem 27 (40): 6825–6836. December 2019. doi:10.2174/0929867326666191209142209. PMID 31814547.

- ↑ Obsessive-compulsive Disorder in Children and Adolescents. American Psychiatric Pub. 1 January 1989. pp. 229–231. ISBN 978-0-88048-282-0. https://archive.org/details/obsessivecompuls0000rapo.

- ↑ "Drug treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 12 (2): 187–97. 2010. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2010.12.2/mkellner. PMID 20623923.

- ↑ Images of Spanish Psychiatry. Editorial Glosa, S.L.. 2004. pp. 376–. ISBN 978-84-7429-200-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=wNIJ4rs7cnEC&pg=PA376.

- ↑ "Antiandrogenic medication of cluster headache". Int J Clin Pharmacol Res 8 (1): 21–4. 1988. PMID 3366500.

Further reading

- "Use of cyproterone acetate in animal and clinical trials". Gynecol Invest 2 (1): 150–79. 1971. doi:10.1159/000301860. PMID 4949823.

- "Antiandrogens". Androgens II and Antiandrogens / Androgene II und Antiandrogene. Handbuch der experimentellen Pharmakologie/Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Springer. 1974. pp. 235–484. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-80859-3_6. ISBN 978-3-642-80861-6.

- "Clinical Uses of Antiandrogens". Androgens II and Antiandrogens / Androgene II und Antiandrogene. Handbuch der experimentellen Pharmakologie/Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Springer. 1974. pp. 485–542. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-80859-3_7. ISBN 978-3-642-80861-6.

- "Administration of Antiandrogens in Hypersexuality and Sexual Deviations". Androgens II and Antiandrogens / Androgene II und Antiandrogene. Handbuch der experimentellen Pharmakologie/Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Springer. 1974. pp. 543–562. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-80859-3_8. ISBN 978-3-642-80861-6.

- "Use of cyproterone acetate (CPA) in the treatment of acne, hirsutism and virilism". J. Steroid Biochem. 6 (6): 827–36. June 1975. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(75)90311-8. PMID 126335.

- "Pharmacology and potential use of cyproterone acetate". Horm. Metab. Res. 9 (1): 1–13. January 1977. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1093574. PMID 66176.

- "Pharmacological basis for clinical use of antiandrogens". Hormonal Steroids. 19. Pergamon. July 1983. 391–402. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-030771-8.50055-3. ISBN 9780080307718.

- "Antiandrogens in the treatment of acne and hirsutism". J. Steroid Biochem. 19 (1B): 591–7. July 1983. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(83)90223-6. PMID 6224974.

- "Treatment of hirsutism and acne with cyproterone acetate". Clin Endocrinol Metab 15 (2): 373–89. May 1986. doi:10.1016/S0300-595X(86)80031-7. PMID 2941191.

- "Das Antiandrogen Cyproteronacetat: Seine Geschichte von der Entdeckung bis zur Marktreife" (in de). Pharm unserer Zeit 17 (2): 33–50. March 1988. doi:10.1002/pauz.19880170202. PMID 2967500.

- "Cyproterone acetate in the management of prostatic cancer". Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 303: 105–10. 1989. PMID 2528734.

- "Antiandrogens: Clinical Aspects". Hair and Hair Diseases. Springer. 1990. pp. 827–886. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-74612-3_35. ISBN 978-3-642-74614-7.

- "Les antiandrogènes. Mécanismes et effets paradoxaux" (in fr). Annales d'Endocrinologie (Paris) 50 (3): 189–99. January 1989. ISSN 0003-4266. PMID 2530930.

- "[Anti-androgen therapy in the female]" (in de). Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 50 (10): 749–53. October 1990. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1026359. PMID 1704865.

- "Cyproterone acetate as monotherapy in prospective randomized trials". Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 359: 85–91; discussion 105–7. 1990. PMID 2149459.

- "Clinical applications of antiandrogens". J. Steroid Biochem. 31 (4B): 719–29. October 1988. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(88)90023-4. PMID 2462132.

- "Use of cyproterone acetate in prostate cancer". Urol. Clin. North Am. 18 (1): 111–22. 1991. doi:10.1016/S0094-0143(21)01398-7. PMID 1825143.

- "Cyproterone acetate in the treatment of sexual disorders: pharmacological base and clinical experience". Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. 98 (2): 71–80. 1991. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1211103. PMID 1838080.

- "The position of cyproterone acetate (CPA), a steroidal anti-androgen, in the treatment of prostate cancer". Prostate Suppl 4: 91–5. 1992. doi:10.1002/pros.2990210514. PMID 1533452.

- "Cyproterone acetate--mechanism of action and clinical effectiveness in prostate cancer treatment". Cancer 72 (12 Suppl): 3810–5. 1993. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19931215)72:12+<3810::aid-cncr2820721710>3.0.co;2-o. PMID 8252496.

- "Cyproterone. A review of its pharmacology and therapeutic efficacy in prostate cancer". Drugs Aging 5 (1): 59–80. 1994. doi:10.2165/00002512-199405010-00006. PMID 7919640.